Since 2015, Lionel Louis has served as the President of Museum Volunteers, a group of 200 men and women who lead free tours of the museums on weekends. Folks are often surprised when they learn he is in charge of the group. After all, his boyish features and wide-eyed enthusiasm make him appear even younger than his 32 years.

But, do not mistake his youth for inexperience. He is a dedicated specialist in Singaporean history, constantly upgrading his knowledge about our shared heritage.

“A docent’s training spans between three to four months,” he explains. “There are mock tours to do and research papers to write. And, once you start guiding, the learning doesn’t stop. Guests tell you new information, and curators give you new angles to talk about. Your tour is always evolving and changing.”

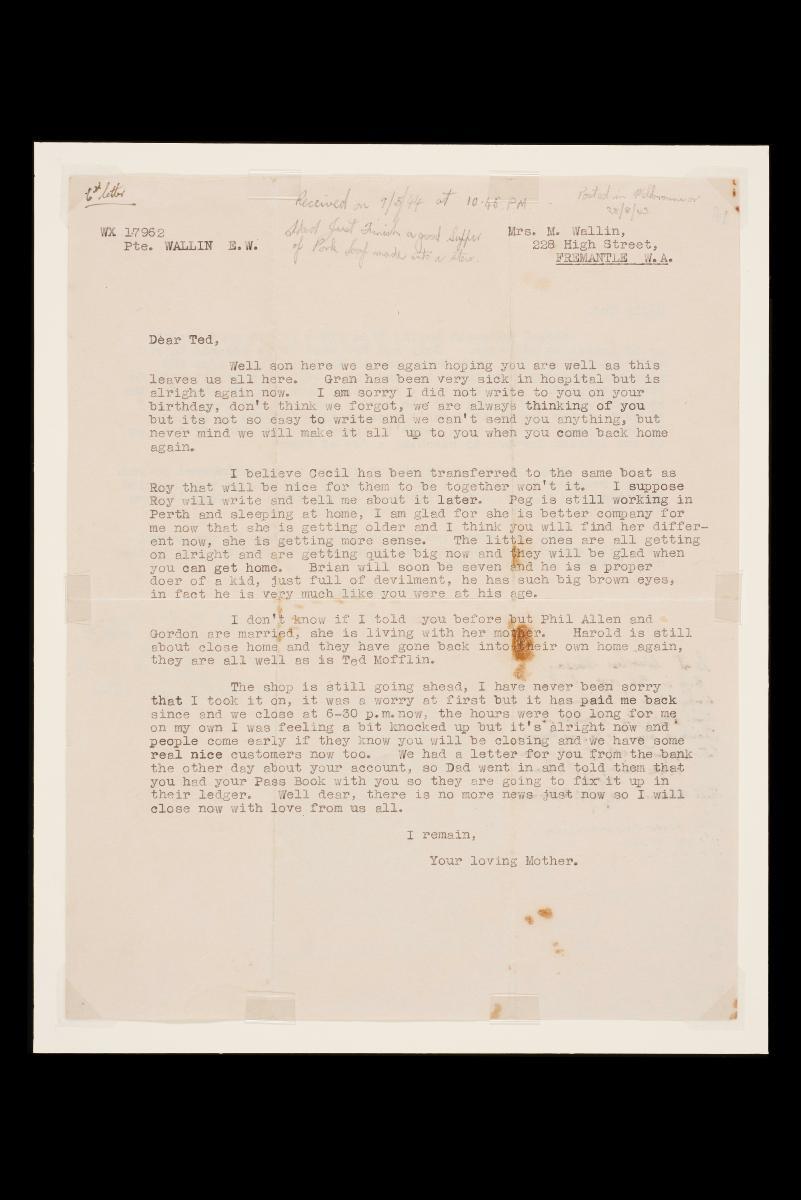

He began guiding at the National Museum four years ago, telling visitors stories about its most prized exhibits, such as the Singapore Stone and the Revere Bell. One of his favourite items on display is John Turnbull Johnson’s 1851 oil painting of the Padang, titled The Esplanade at Scandal Point. He enjoys pointing out all the easily missed details on the canvas, such as the presence of Orang Laut and Arab traders, as well as the view of the Armenian Church,St Andrew’s Church and Government House (now known as the Arts House).

Beyond textbooks

He also takes great pleasure in revealing secrets of the past that were not taught in school. For instance, history textbooks often neglect to mention that Colonel William Farquhar had two wives: one in Scotland and another in Malacca. The punchline to this anecdote is that one of his descendants, via his Malaccan wife Nonio Clement, is the Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

Towards the end of his tour of the History Gallery, he begins sharing tales about independent Singapore. “There’s a lot of personal stories I can tell people,” he says. “Like, there’s the Stop at Two poster. I like to tell guests that we’re a young nation, and our policymakers may make mistakes. We’re still learning from them.”

Occasionally, Lionel has been involved in slightly more unusual tours. For instance, as part of the Singapore Heritage Festival 2016, he was trained by a theatre company to lead dramatised tours. He ended up playing three different roles: a 14th century villager, an early 20th century Chettiar and the Chettiar’s son who became a civil servant. His fellow guides played roles like black and white amahs, rickshaw pullers and Japanese soldiers. “It was very draining, but also very fun,” he says.

Mind you, not all volunteers need to be such dynamic storytellers. He points out the many other roles one can play at the museums, such as welcoming visitors as a host, or ensuring that they keep to the rules in the exhibition space as a gallery sitter.

Planning ahead

As the President of Museum Volunteers, Lionel has many responsibilities besides guiding. Together with a committee of 14 other people, he ensures that the guides are properly scheduled, trains new volunteers, organises Learning Days and collects feedback for the museums.

He is also attempting to create better documentation and a structured long-term strategy for his group, so that they can remain relevant in these changing times. But, planning ahead can be difficult, since the museums themselves are constantly changing and seeking new directions.

Surprisingly, the artefact that moves him the most is not a religious statue or a war relic. It is a Tamil language typewriter, capable of printing the 200-plus combinations of characters used in the script. The object reminds him of his own Tamil lessons as a schoolboy in the 1990s. Back then, he did not think much of the fact that Tamil fonts were available on the computer. But, he now realises that this was only possible because people who loved the language invented new ways to bring it into the 20th and 21st centuries.

He is grateful not only to the museum but also to the people who donated the typewriter: the family of the late Tamil poet Viswanatha Ikkuvanam Iyer. Their generosity has enabled him to gain a new appreciation for his heritage.

“Museums play a very important role in society because they’re a visual documentation of people and stories,” he says. “It’s important to document your own stories, so that museums can share them with people.”

By Ng Yi-Sheng