By Sheryl Lee and Vidya Murthy, with 3D images contribution by Dave Lee

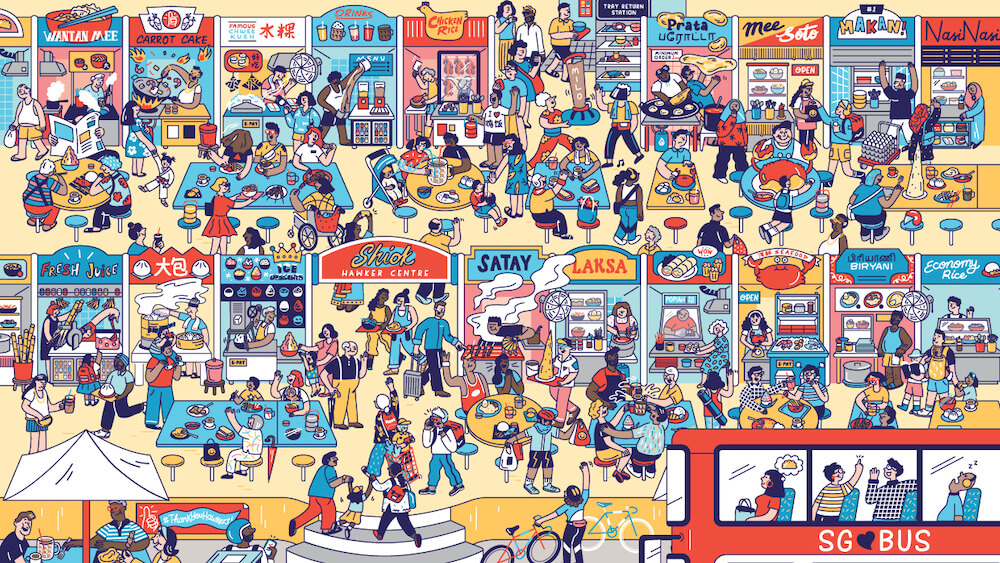

“There is probably no city in the world with such a motley crowd of itinerant vendors of wares, fruits, cakes, vegetables…” wrote author John Cameron of Singapore in the 1860s. Indeed, Singapore is home to diverse hawkers and hawking practices accompanied by a vast material culture.

Get a glimpse of the myriad ways in which hawkers were represented. Learn about the practical struggles they faced, the environments they operated in, and shifts in hawking practices—including stricter licensing and regulations—that led to the birth of integrated food spaces or the hawker centres in Singapore that we know of today. Discover also, the tools and utensils of their trade, and how this was intricately tied to the experience of eating hawker food.

See how our rich hawker heritage, having evolved with technological advancements and shifting consumer tastes, continue to define Singapore’s social and culinary experiences.

Hawkers of the Past

Hawkers in Singapore have been written about, photographed, sketched and represented since the late 19th century. From the exoticised figure posed in a studio, to the gritty, realist picture of a humble man selling his wares on the street, and even the nostalgic rendering of a bygone tradesman, the varied ways in which hawkers have been represented reveal the diversity and ubiquitousness of their trade.

1860s

2015-00465

The slender, posed hawker with his wares seems to embody the “travelling cook [shop]” described by Cameron in his visit to Singapore.

Notice how he stands, resting his hands on his kandar (wooden or bamboo) pole; his rough-woven baskets containing condiments, containers, plates and a charcoal stove in view.

Carte-de-visite photographs such as these were often sold as souvenirs to tourists. This image was taken by G. R. Lambert, a prominent 19th century commercial photographer whose shop, G. R. Lambert & Co. (1867–c1877), was located on High Street. He was known for documenting images of the island, examples of which are in the National Museum collection.

Late 19th century

XXXX-12899

Here we see two men of Indian origin in traditional clothing. The man on the left holds up a bread with his right hand, while the man on the right holds onto a basket tilted strategically for the viewer’s gaze.

See how his headgear is tied differently from that of the other man? Its untied manner suggests that the basket has just been brought down from his head.

Many South Asian migrants in 19th century Singapore took to hawking for a livelihood. These people were often called, sometimes incorrectly, Bengali (or Bengalee) which generally referred to those from Northern India or present-day Uttar Pradesh.

Early 20th century

1995-03539

Featured in this colourful postcard is a young hawker selling cakes, laid out in a basket before him. The boy sits naturally and has a casual disposition, as if caught on candid camera.

Modern technologies of reproduction and travel helped to popularise such postcards in the late 19th or early 20th century. This visual genre was widely circulated and avidly collected.

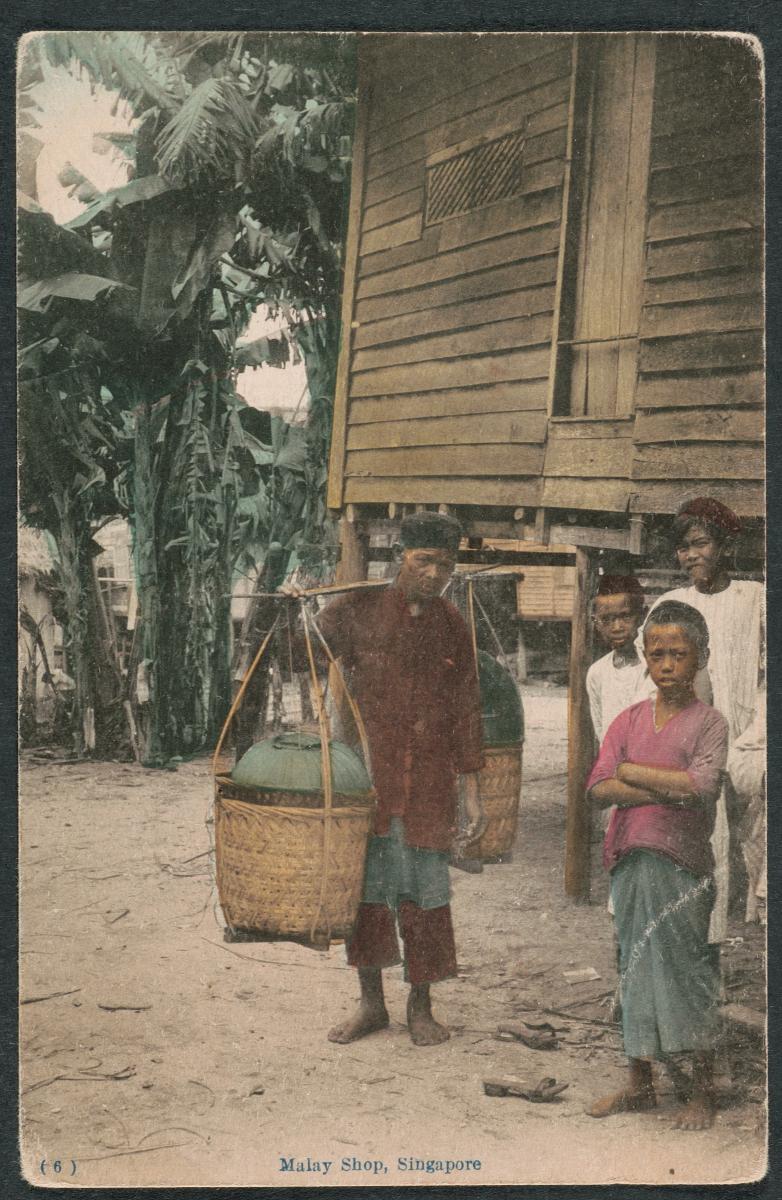

c1900

1992-00965

Donated by Tan Khiang Khoo

Wearing a songkok (cap) and a kain panjang (waistcloth), this satay seller carries his satay sauce, containers and stove with the aid of a kandar pole resting on his shoulders.

Satay comprises of tenderised and spiced meat cubes skewered on wooden sticks and grilled over charcoal fire. It is usually served with ground peanut sauce, diced cucumbers, onions, lime slices and sometimes with ketupat (steamed rice dumplings in plaited coconut leaf).

Malay and Javanese satay hawkers usually operated on Middle Road. Later, some set up stalls near the Esplanade and came to be known as the Satay Club.

Click on the 3D image for a closer look.

Khoo Tee Seng

1965

2000-08129

Dressed in clean clothing and betraying none of the effects of his labour nor the grime of the street, this watercolour paints a charming vignette of a noodle hawker.

He rests his arm on a tray, on which an array of sauce bottles, soup containers, plates and chopsticks are placed. Seated in front of him are two diners—each with a bowl and pair of chopsticks in hand. Laid out on the makeshift table are other bowls and condiments for the customers’ use.

Lim Mu Hue

1966

1999-00817

A satay seller is depicted seated on a stool, fanning his meat-on-sticks. The smoke billows in curly wisps.

This highly condensed memory-image of the hawker is created by Lim Mu Hue 林木化 (sometimes Ling Mu Hua, 1936–2008), one of Singapore’s leading artists, well known for his woodcut prints.

The hardships faced by hawkers and other members of the working class was a popular theme for artists during the 1950s. The theme persisted even in woodblock printing which developed in Singapore in the 1930s, as well as in Malayan art that took shape in the late 1950s and 1960s.

3D model: satay hawker figurine

Have fun checking out the figurine of a satay hawker!

Hawkers at Work

Hawkers were commonly found in places where people would gather—on the streets, at the riverside and in rural areas. Carrying their wares under the harsh sun or laying out their produce for sale, these itinerant vendors were easy to spot.

The following images of hawkers at work not only reveal the physical labour involved in their trade, but also their social status and the precarious life they led. Aided by advanced camera and printing technologies, amateur photographers—many of whom were tourists, travellers and locals—captured these snapshots of everyday life of food vendors in Singapore.

1900s–1930s

2007-00719

With the sun bearing down on him, the barefooted hawker shoulders the weight of his trade. Here, the photographer captures the long, sandy road lined with coconut trees.

In the early 20th century, Seletar was home to thriving rubber plantations. The inhabitants of villages that sprang up close by in order to house the plantation workers and their families probably patronised hawkers such as the one shown here.

1915

2007-00866-127

Barefooted and dressed in simple clothing, this hawker squats in the middle of a field with his kandar pole, umbrella and beverage dispenser with glass.

This snapshot was taken at the Tanglin Barracks, where this itinerant hawker probably eked out a small living by selling food and beverages.

This image is from an album of photographs taken by Sergeant B. W. Turner in 1915. He served in the King's Shropshire Light Infantry and came to Singapore in February 1915 to assist in suppressing the Sepoy Mutiny. Built in 1861, the Tanglin Barracks served the British infantry battalion till the autumn of 1942.

Early 20th century

1991-00371

With a spoon and bowl in hand, the children are seen squatting and eating their meals on makeshift pathways made of planks.

The rustic-looking houses on stilts that surround them give one a sense of the conditions in which hawkers operated in.

Besides plying their wares on the streets, food hawkers such as the one shown here went regularly to kampongs (rural villages) as well.

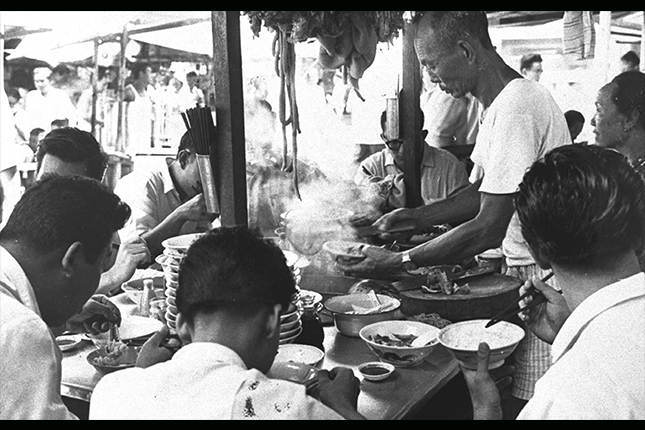

1950s

2000-03733-515 (also see 2000-03733-495)

Hawking food on the streets provided a living for many hawkers. With little capital and skill, they sold affordable food to the working classes, including coolies and clerks.

These hawkers were usually found at street corners, football grounds and toddy shops during midday as well as at tea time. Several hawkers of Indian origins—as seen here—often sold tea, ginger water and buns.

c1950

XXXX-15565

Getting up as early as 3 a.m., women such as the hawkers seen here carried cabbages, beans, lady’s fingers, yams, pumpkins and cucumbers in two huge baskets suspended from kandar poles held across their shoulders.

They would settle at a spot in one of the back lanes or alleys and lay out their produce in dish-shaped rattan baskets in wait of customers through the day. Some of these street vegetable hawkers were employed by wholesalers to sell their perishable stock of vegetables and fruits.

The Teochew community, for the most part, controlled the fruits and vegetable trade. They had their own association near Ellenborough Market.

Early 20th century

2007-50879

“What’s to be done about the hawkers?” complained a newspaper writer in 1949. Indeed, food hawkers were described and seen as being singularly responsible for the poor hygiene in the city.

The most maligned of all were drink hawkers whose source of water and personal hygiene were called into question, especially because many would wash their glasses by repeatedly dipping them into the same bucket of water.

By the turn of the 20th century, authorities began to impose regulations on street hawkers in an attempt to alleviate the hygiene issues that plagued the city.

Licence to Operate

While food hawking offered a livelihood for many, especially the impoverished, their itinerancy posed a problem for the authorities. Hawkers were perceived as unsightly, a threat to public health, and were also associated with criminals. To address these issues, the Hawkers Advisory Committee (1931) and Hawker Inquiry Commission (1950) were set up to regulate vendors.

The government even carried out an island-wide registration exercise from the 1960s to the 1980s, relocating hawkers from the main streets to the side or back lanes and stepping up enforcements against illegal hawking. Designated spaces for hawkers such as markets and hawker centres were also constructed.

1933

2008-06731

Gift of Low Sze Wee

This is a receipt issued by the Municipality of Singapore to Ah Nang, an intinerant hawker, acknowledging the dollar fee he paid for the license.

The government sought to control the number of hawkers, the hours of their trade and the places in which they could operate.

Following the passing of the licensing laws in 1906 and 1907, night hawker stalls began to be regulated. This legislation later extended to include itinerant and day hawkers.

1938–1939

2007-50928-194

The license issued to this hawker can be seen clearly affixed to the handle of her kandar pole. By the 1930s, there were about 6000 licensed itinerant hawkers and 4000 unlicensed ones.

The Singapore River by which the vendor sits was dramatically transformed after a massive cleaning exercise held between 1977 and 1987. During that time, the government expedited the construction of markets and hawker centres, progressively moving itinerant street hawkers into permanent establishments.

1950

2008-06078

Gift of Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce & Industry

This is a sign in Chinese issued by Singapore Municipal Commission which reads “Hawkers Prohibited” (禁止小贩, jìn zhǐ xiǎo fàn).

Signs like these were placed at designated areas where hawking was strictly prohibited. They were an indication of the then government’s ongoing efforts to improve the city’s sanitation, as well as to organise street and itinerant hawkers.

1950s

2000-00595

The City Council, formerly known as the Municipal Commission, was the local government authority that was tasked with managing public utilities and infrastructure in the city area.

In 1957, the Council became a 32-member elected body. Following the elections that year and the landslide victory for PAP, Ong Eng Guan was appointed Mayor of the City Council.

1957

1999-02302

Licenses like these were issued to street hawkers by the government to regulate them. While hawkers provided necessary services and goods for Singapore’s population, they also posed many problems for the authorities in both the colonial and post-independence eras.

Licensing hawkers was a way to regulate them by making them follow certain rules governing food hygiene and waste disposal. Over time, street hawkers were relocated to state-built, roofed shelters and markets equipped with amenities such as running water and electricity. These would eventually become what we know today as hawker centres.

1960s

2009-01683

In addition to peddling with their containers balanced on kandar poles, beverage hawkers also sold hot drinks in mobile carts such as this.

Popular malt drinks such as Ovaltine and Horlicks that we still see and enjoy today can be seen in their powdered, tinned forms on the cart. Jars of snacks, along with tea and coffee, were usually part of the menu. Utensils, the all-important license, as well as colourful posters and calendars can also be seen as well.

c1973

2014-00621

This pamphlet depicts the importance of maintaining a clean hawker stall. In the illustration, the clutter, debris and malodour of an old hawker stall—demonstrated by a customer holding a handkerchief to his nose—is juxtaposed with a shiny new stall with clean, designated areas for eating.

In a bid to transform Singapore into the garden city of the region, the then government launched a series of campaigns known as “Keep Singapore Clean” in 1968. This booklet was part of that effort.

Mobile Kitchens

Hawkers employed a wide range of tools and equipment to carry out their trade. These include (1) transportation aids such as kandar (wooden or bamboo) poles, baskets, carriers and carts that were used to fit their cooking equipment or store their cooked food, (2) devices such as kerosene lamps that were used to light up their street stalls at night, as well as (3) utensils and cutlery which hawkers used to cook and serve their dishes. For many of the roving hawkers, portability and durability were key considerations in selecting their tools. Some of these tools are still being used by hawkers today.

1960

2006-00311

At a time when peddlers roamed the streets of Singapore to market their items or food, a kandar pole—or carrying pole—would have been used to aid the peddler in shouldering their load. Baskets containing food or other items were hung on both ends of the pole, which would then be balanced on the shoulder of the peddler.

Be it rain or shine, near or far, peddlers would have relied on this seemingly plain and simple tool to carry their items to be sold in markets, roadsides, or along the streets.

→ Click to the next image to see a peddler in action.

c1950

XXXX-15573

Taking centre stage in this photograph is a kandar pole with a large rattan basket hanging off each end. It would have probably been used to transport containers and bowls that were used to store the food the peddler was selling.

Notice how the rattan intertwines at the apex of the container to form a hoop? The peddler would be able to slot the kandar pole through this hoop and balance it along with other equipment and utensils. Imagine how difficult it would have been to carry all the equipment without the handy kandar pole!

1970s

2006-01661

Baskets like the one featured here were essential for Singapore’s hawkers to transport their wares. Many hawkers travelled through Singapore’s streets looking for customers and thus needed sturdy baskets like this.

This basket is made from rattan, a palm native to tropical regions such as Southeast Asia. Singapore was known for its high-quality rattan goods and was a centre for the rattan trade which flourished in the 1960s and 1970s.

→ Click to the next image to see a depiction of hawkers using these baskets.

1960

2000-03867

Sturdy and easy to carry around, these woven rattan baskets also doubled up as trays in which food items could be displayed. Just look at the array of fresh produce that this group of itinerant hawkers are selling!

Hawkers like the women shown here provided cheap and convenient access to food and fresh produce that fed the rapidly growing population in the 1960s.

1960s

2006-01660

Toiling through the night, street hawkers needed a dependable light source to keep their businesses running. Many used kerosene pressure lamps such as this in the 1960s.

To light the lamp, the base would first be filled with kerosene. Then, the small dish below the lamp’s mantle would be filled with methylated spirit, which was then ignited. Lastly, the hawker would pump the lamp to spray vapour from the kerosene.

While this process may sound complicated, many hawkers relied on these lamps because a reliable supply of electricity was limited in those days!

c1950

XXXX-15575

Hanging at this hawker’s stall are two kerosene pressure lamps. These lamps not only provided hawkers with light to work by, but also informed customers if the hawker stall was open for business at night.

While these lamps became less popular among hawkers as Singapore’s electricity supply improved, they are still used by overseas street hawkers, such as those in Indonesia and Thailand.

1960s

2000-07304

Seven times brighter than the light produced by kerosene lamps was that of carbide or acetylene lamps, also commonly used by hawkers.

In those days, carbide/acetylene lamps were made by the local tinsmith. They would collect tins and fix a delivery tube and flame nose onto the cover of the tins. Carbide would then be placed in the tin and water poured over it. This chemical reaction would produce carbide gas that would be channelled up the delivery tube to produce a flame. Such lamps are remembered for its foul smell and hissing noise.

1960s

XXXX-09122

Street hawkers used clay charcoal stoves such as this to cook or heat up their dishes. Its small size made it convenient for hawkers to transport, manoeuvre and store. To operate the stove, charcoal is fed through the small opening and burned.

Over the years, the material and form of stoves have evolved, along with the fuel used by food hawkers in their practice. More energy-efficient alternatives such as natural gas and electricity gradually replaced these clay stoves.

c1950

XXXX-15572

In this phototograph, a hawker is seen in conversation with his customer under the illumination of a carbide/acetylene lamp. His collection of utensils and hawking equipment such as a clay stove is also captured.

Can you spot the lamp and stove in the photograph?

1970s

2006-01389

Hawkers who sold char kway teow (fried, flat noodles) used baskets such as these to hold or transfer charcoal.

In some Chinese dialects, they were called pungki [蓬基 (péng jī)] or punki [畚箕 (běn jì)], which means “scooped-shaped basket” or “bamboo or wicker scoop”.

The downward angle and open top of this type of basket made it convenient for hawkers to retrieve charcoal pieces. Pungki is also used in mining and agriculture.

1960s

2006-01390

This charcoal tong prevented char kway teow hawkers from burning themselves when adding or removing charcoal from a clay stove.

Hear how Mdm Kok Ying Oi talks about the use of charcoal in “Hands: Gift of a Generation—Mdm Kok Ying Oi”.

1970s

2006-01671

Gift of Nelson Li

To whip up tasty dishes, many hawkers made use of a cast iron wok. The materiality of such woks facilitates even heat distribution and resistance to strong flames.

The material and structure of such woks make them a versatile cooking tool, allowing for a variety of cooking styles such as stir-frying, steaming, pan-frying, deep-frying, boiling, braising, searing, smoking and stewing.

→ Click to the next image to see a type of brush needed to clean a wok.

1980s

2006-01402

With so many customers to attend to, hawkers needed an easy way to clean their equipment. The bamboo splints on the brush shown here make it effective in getting rid of stubborn stains and burnt particles quickly, without the need for the wok to cool.

Whipping up Familiar Favourites

Have you ever wondered how popular hawker dishes such as satay (skewered meat) and chicken rice are prepared? You will be surprised at some of the practical and ingenuous ways that hawkers used to cook and promote these local favourites. From intricate moulds for kueh bahulu (mini sponge cakes) to charcoal grills for satay, the uniqueness of some of these cooking utensils and implements are as iconic as the dishes themselves, and a testament to the diversity of our hawker cuisine.

1940s–1970s

1994-04227

Before we had modern-day food delivery apps, travelling noodle hawkers came up with a unique way of taking orders from customers with the help of this bamboo striker.

Striking various parts of the bamboo using different rhythms produced unique variations of the “tok tok” sound, each representing a different noodle dish.

Upon hearing the rhythmic striking, customers would lower their baskets from the windows of their houses with their order, which hawkers would replace with the dish. Once done, customers would then lower the empty bowls with the payment.

These hawkers came to be known and fondly remembered as “tok tok men” and their dishes, “tok tok mee”.

B-0765

This brass pot was likely used by hawkers to cook noodles. Water would have been poured into the larger pot and boiled, while noodles and other ingredients were placed in the smaller compartments to be cooked.

Noodles have long been a staple sold by many hawkers in Singapore. For dock labourers and other members of the working class, a bowl of noodles served as an affordable, comfortable and filling meal.

1940s–1960s

1994-04250

Characterised by its mesh wire base and long bamboo handle, this object goes by a variety of names, but is most generally and interestingly known as the “spider”. It is most often spotted at noodle stalls, being used by hawkers to strain noodles.

c1960

1998-00326-089

This photograph shows a pushcart hawker at work during the mid-1900s. On his cart sits a large metal tray on which bowls and spoons are stacked and placed. There is also a large glass shelf where food and drinks could be kept or displayed. A cooking pot would have been fitted into the cart for him to prepare his dish.

The roof attached to his pushcart would also have shielded the hawker from unfavourable weather conditions such as the hot sun and rain.

1960s

2003-00236

Gift of Tan Chin Kim

Carts such as the one shown here were once almost-ubiquitous among hawkers in Singapore. This cart, in particular, was used by a hawker to sell kueh tutu—small steamed cakes made from rice flour and filled with ground peanuts, grated coconut or gula melaka (palm sugar).

These kuehs (local cakes) were made by steaming rice flour in specially designed moulds. The method of making kueh tutu and its ingredients share strong similarities with that of putu piring.

1970–1999

2004-00179

Gift of Angeline Khoo

This grill was used to make one of Singapore’s most iconic hawker dishes, satay (skewered meat). Satay consists of grilled meat skewers served alongside peanut sauce and other condiments. The meat was usually grilled over a charcoal fire.

For this grill, the charcoal would be placed in a trough at the bottom and lit. The meat skewers would then be placed across the top of the grill to cook. To ensure that the meat was grilled properly, hawkers would fan the coals to ensure even distribution of heat.

→ Click to the next image to see another important object needed to cook satay.

1940s–1970s

1994-04331

This mug is an example of the type of containers hawkers used to contain oil and other essential condiments for grilling satay.

Hawkers continuously brushed oil onto the meat as it was being grilled to give it the perfect glaze.

→ Click to the next image to see a satay hawker in action.

1970s–1980s

2008-04128

This photograph shows a satay hawker at work. In front of him are a grill and a mug like the ones you saw in the previous images.

Notice how the skewers of meat are lined up on the grill. The hawker holds in one hand a rattan fan to fan the fire, while his other hand holds a brush that he uses to dip into the condiment-filled container.

Imagine if you were one of the customers in the background, enjoying piping hot satay fresh off the grill. How lucky you would be!

1950s–1970s

2006-01386

The container featured here was used to keep ginger or other condiments that were typically used to garnish chicken rice. When the lid is closed, the container would have kept the condiments fresh and protected from pests.

→ Click to the next image to see a depiction of a typical chicken rice stall in hawker centres.

2001-03226

This painting by Lim Yew Song depicts a typical chicken rice stall in a hawker centre. Chicken rice is believed to have been introduced by Hainanese immigrants to Singapore, based on a dish made in Hainan that used the Wenchang chicken (文昌鸡).

In Singapore, the Hainanese incorporated other influences such as using younger chickens cooked in the Cantonese style. The dish eventually evolved into what we now know as chicken rice—an iconic hawker dish both at home and abroad.

1980s

2006-01428

Gift of Chew Tee Kim

This cleaver was from the famous Nam Kee chicken rice coffee shop. It is much larger than standard knives and is specially weighted to allow the hawker to slice through meat easily.

It must have taken a great deal of skill to wield this type of cleaver—one alone can weigh up to 1.5 kilograms! Even a moment of inattention could be dangerous for the hawker. Many hawkers in Singapore still use these cleavers today.

1970s

2006-01385

This traditional knife sharpener comes in the form of a stone. Sharpening stones like these were often used to sharpen cleavers like the one featured before.

Hawkers needed their cleavers to be sharp in order to cut through food with precision and ease. Some itinerant hawkers even provided knife sharpening services to the public.

c1927

2000-03950

Hawkers used chopping boards like this to chop the ingredients they required for their dishes. The durability and sturdiness of chopping boards were important considerations.

Wooden cutting boards were known to be the most suitable surface when chopping with knives. However, they needed to be scraped clean using choppers after use and had to be washed more thoroughly as opposed to their plastic or bamboo counterparts. They also required regular oiling to prevent splitting and warping.

1900–1969

1994-05386

Bird’s nest drink, a Chinese delicacy, was sold on the streets by hawkers back then. They would transport and sell the drink using this special brass carrier with a handle. It features an open-top tray on which cups and small containers could be placed, as well as a hinged door with a clasp within so the contents could be securely kept.

Click on the 3D image for a closer look.

1940s–1960s

2003-00257

Gift of David Ng

This mould was used to make kueh bahulu (also known as kuih bahulu), or mini sponge cakes made from eggs, sugar and wheat flour. It is a popular treat at festive occasions such as Chinese New Year and Hari Raya.

Traditionally, kueh bahulu were baked using charcoal placed on the lid of—and under the—mould. Different designs are etched into the mould, including fish and flower patterns. The cakes would take on the shape of these designs as they cooked.

“Kueh”, or “kuih” in Bahasa Melayu, refers to a wide variety of traditional local cakes still sold today.

Click on the 3D image for a closer look.

3D model: bird’s nest drink carrier

Have fun checking out the carrier and container for bird’s nest drink!

3D model: kueh bahulu mould

Have fun checking out the kueh bahulu mould!

Time to Eat

Back in the day, when hawkers lined five-foot ways (covered walkways) and peddlers roamed the streets, customers sat on stools and low tables along the roadside to have their meals. These pushcarts or low tables were equipped with eating utensils such as chopsticks and bowls, so customers would eat in front of—or near—the hawkers. In some cases, they even propped themselves onto a high stool and used the cart itself as a tabletop. Peddlers and street hawkers had to co-exist with shophouse owners, and this continued even with the introduction of more organised, designated areas for street hawking.

1960s

1994-04318

Gift of Ang Yang Buay

This simple stool was a common sight in Singapore’s five-foot ways, which were covered walkways between the street and the shop entrance. Food hawkers and other traders plied their goods and trade along these five-foot ways. The hawkers would place these stools and low tables at makeshift eating areas for their customers.

1938–1939

2007-50928-276

This photograph captures a family eating at a hawker stall located along a five-foot way. The family gathers around a low table, each sitting on a stool like the one shown earlier.

These makeshift eating areas were equipped with utensils such as bowls, plates, as well as holders that held chopsticks and spoons. Imagine people weaving in and out of the shops while you were eating!

1960s

2006-01401

Chopsticks is a type of traditional Chinese eating cutlery, supposedly brought to Singapore by Chinese immigrants. The socio-cultural practice and rules on the “proper” use of chopsticks has its own long history.

Sticking your pair of chopsticks into a bowl of rice or crossing your chopsticks would likely earn you shaking heads of disapproval from the elderly because of superstitious beliefs.

What is your way of holding chopsticks?

1960s

2006-01391

Chopstick holders like the one featured here were once commonly found at makeshift hawker stalls or hung up on the walls of noodle shops. The hole at the centre of the apex was used to secure the holder.

Explore more chopsticks and chopsticks holders in the National Collection.

1970s

2006-01407

With a long, thick handle that extends from a concave well, this spoon was commonly used to drink soup or eat cooked dishes such as noodles. It would often be made of porcelain, though you will find similar wooden, metal and plastic counterparts.

1970s

2006-01405

Roosters are a popular motif in Chinese culture. It is often thought to symbolise good luck, in part due to its pronunciation “jī” (鸡) sounding very similar to the Chinese word “吉” (jí), meaning “lucky” or “auspicious”.

As pronouncing the word in Hokkien sounds like “family” or “home”, depicting roosters on porcelain bowls were also thought to bring good fortune and prosperity to the household. Such bowls were also used at hawker stalls.

1950s–1960s

1994-04247

High stools like this used to be placed at hawker stalls for customers to sit on. These were necessary as some of the hawker stalls were quite tall and it would have been difficult to eat without being propped up on these high stools.

→ Click to the next image to see how these wooden stools were used.

c1950

XXXX-15583

Propped up on high stools in front of the hawker and using the stall itself as a tabletop on which to dine, these customers can be seen digging into their bowls. Sitting shoulder to shoulder, and in close proximity to the hawkers, one would imagine the flow of conversation that arose from such an eating experience.

This experience changed somewhat after street hawkers shifted into permanent hawker centres. But people from all walks of life can still come together to share and enjoy the hawker fare that Singapore has to offer today.

Try spotting the differences between the hawker stalls then and hawker centres now.

Explore more photographs of old-time hawker stalls in the National Collection.

c1980s

2008-05452

Recognise this place? Many Singaporeans, and even foreigners, would be familiar with Newton Food Centre. Opened in 1971, it was the first hawker centre built in a garden setting, and was part of then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s vision of a garden city.

Newton Food Centre was even featured in the 2018 movie, Crazy Rich Asians. Many street hawkers, such as those plying their trade in Orchard Road and Marine Parade, were relocated to this hawker centre. Here we see how the once-itinerant hawkers have been united under one roof to create an integrated food centre.

1970s

2002-00973

“Tikam-tikam” is a Malay term for “game of chance”. Tikam-tikam boards—consisting of folded slips of paper stuck on a piece of cardboard— were usually carried by roving drink stall hawkers.

For a small price of five to 20 cents, children could pull a piece of paper off the board. Printed on the reverse side of the paper would have been the prize they won—usually small toys or snacks such as candy floss.

Although the game was outlawed in 1961 for encouraging gambling, it remained popular among Singaporeans as a form of simple childhood entertainment well into the 1980s.

Have a Sip

How did our drinking utensils and environments evolve? Whether it was the shift from using manual coffee grinders to automated grinding machines, or how we used to have tea at makeshift stalls but now gather at a kopitiam (coffee shop), the ways in which our drinking culture and material have changed tells a rich story of consumer habits and tastes.

With technological advancements, beverage manufacturers also began to embrace innovative packaging. While consumers were used to drinking out of traditional porcelain cups and glass bottles, portable canned drinks, and later, Tetra Paks, brought greater convenience to them and hawkers alike.

1992-00695

One of the most iconic items of the Singapore kopitiam, this porcelain cup with its accompanying saucer is typically characterised by matching motifs on the cup, saucer and spoon.

In addition to floral designs such as the one seen here, some of the big-name coffee shops would print their business names or advertisements on the porcelain sets.

The stout porcelain cup ears allowed customers to enjoy their hot drinks without scalding their hands. The saucer was useful too, enabling service staff to juggle a few cups at a time on their hands and wrists, as well as doubled up as plates for food such as toast and eggs.

1927

2000-03943

Before mechanised coffee grinders became popular, many coffee shops would have had a manual coffee grinder like this.

Prior to brewing a cup of kopi (coffee), the coffee beans must first be roasted in charcoal, then caramelised with sugar and butter or margarine. This process gives the kopi its unique aroma and flavour. The roasted beans are then ground into powder using grinders like the one featured here.

1970–1999

2006-01613

This coffee kettle with its signature long spout was used to brew kopi. Kopi is brewed using the traditional “coffee sock” method, where a filter bag made of muslin is first filled with coffee powder and placed inside this kettle. Finally, boiling water is added into the kettle. The result would be a strong brew with intense aroma and flavour.

1970–1999

2006-01617

This ladle would have been used to scoop water into a brass kettle for the brewing of coffee or tea. Such ladles are still used by drink hawkers today, although they may be made of other materials such as plastic.

1960s

XXXX-04115

This brass boiler was used by hawkers to store water. Water would have been poured into the compartments, and then placed over a coal fire or other types of long-burning fuel to boil. Hot water could then be dispensed by turning the taps.

With the arrival of alternative boiler containers and the introduction of other methods of tea-brewing, this type of container was gradually displaced.

1960

2000-03868

This painting depicts a hawker selling teh tarik (pulled tea). He is seated with his customers who are enjoying some tea and snacks. On the left, there is a kettle and a boiler. Can you see the tap at the side which the hawker would use to dispense water?

Teh tarik is made by first adding water to tea dust (tea leaves ground into powder form). The tea is then steeped before condensed milk and evaporated milk are added. The resulting mixture is strained into a tin mug and poured from one mug to another at a height, repeatedly, until a layer of froth forms. This action is called “pulling” or “tarik” in Malay.

1970s

2006-01413

In the mid-1900s, Green Spot was a popular drink sold in Singapore. Unlike its name, it was a signature orange-coloured, flavoured drink that was sold exclusively in glass bottles.

Singapore had a vibrant packaged drinks market, and local and international companies produced a plethora of beverages for sale locally.

Explore more glass-bottled drinks in the National Collection.

1970s

2006-01411

In the mid-1900s, an essential item for drink stall hawkers was the metal bottle opener. This object easily opened the metal caps that tightly sealed glass bottles.

First created in 1892, these metal caps were designed to prevent contamination and the leakage of carbonated gas.

Over the years, bottle openers have evolved in shape, structure, material and aesthetic.

1980–1999

2015-02070

Beyond freshly brewed drinks such as kopi, canned drinks like these were also popular among the local community. Here are two cans of soya bean drinks manufactured by Yeo Hiap Seng.

The consumption of soya bean milk was first popularised in Singapore by Yeo Hiap Seng. The company’s first bottled range, Beanvit, was very well received when it was launched in 1954. As Beanvit became a success, Yeo’s began to offer many other packaged drinks such as iced lemon tea and chrysanthemum tea.

If you take a closer look at the drinks stalls in hawker centres today, you will notice that some of them still brew soya bean milk in-house, by hand!

1980–1999

2015-02071

These rectangular Tetra Brik cartons containing chrysanthemum tea are examples of another popular drink manufactured by Yeo Hiap Seng. This packaging was made possible through the introduction of an ultra-heat treatment process that kills any microorganisms in the drinks. It gave the beverages a longer expiry date.

Known for its cooling properties, chrysanthemum tea is especially useful for beating the heat in Singapore. Imagine sipping on a chilled pack of chrysanthemum tea while you are out and about in the sun!

Late 20th century

2006-01624

This block for printing labels on paper bags was used by a local coffee company, most likely to label their packaged ground coffee powder before they were distributed to kopitiams for sale.

Several enterprising cottage industries that thrived in Singapore used such blocks to advertise their services. These small-scale units were usually family-run and contributed to the local economy then, providing jobs for many including women.

c1960s

2009-02777

This is an example of an advertisement printed on a paper bag. Heap Lee Co. Pure Coffee promises “full flavour and exclusive fragrance”. From the printed illustration, it appears that this coffee was packaged in tin cans as well.

Packaging was a means by which businesses could market their brand names or do product placements.

Brewing Nostalgia: Kopitiams

Coffee is best enjoyed leisurely, and the open space as well as loosely arranged furniture in Singapore’s traditional kopitiams (coffee shops) create an informal setting and ambience of leisure conducive for this. With a constant supply of hot and affordable beverages, kopitiams encouraged socialisation and casual conversation within the community.

The kopitiam furniture featured here have become iconic. As examples of local design, they also show the influences of late 19th and early 20th century international forms and techniques in furniture making.

1930s

1992-01358

Made in Singapore, this long counter is believed to have stood in a coffee shop in Kallang. While the top served as a surface for holding objects, the inset glass case could have been used to display snacks.

At times, counters such as this were placed in the middle of the shop, effectively dividing the space. Customers would sit at the tables out in the front, while the kitchen and washing areas were situated at the back.

1960s

2008-06988

This marble-top table set on strong wooden legs was once a mainstay of coffee shops. The hexagonal—and sometimes round-shaped—tables encourage social interaction as everyone faces the centre and can maintain eye-contact.

Such tables also facilitate the sharing of food without the need to pass sharing platters down the row as would be the case with rectangular tables. Placing two or more of these tables together could also accommodate large groups of people.

1960s

2016-00405-001-005

These contoured, spindle-back and moulded plywood chairs, known as “bentwood chairs”, were a common sight in kopitiams.

The bentwood chair was first invented by Michael Thonet, who created the technique of bending wood through chemical and mechanical means.

Its popularity abroad in fashionable Viennese cafés earned it the title of “coffee house or bistro chair”. By 1930, close to 50 million of such chairs had been sold, including those to the Straits Settlements.

Shipping these chairs was easy because the chairs were made of pre-fabricated pieces and could be taken apart, flat-packed and re-assembled. They have, for the most part, been replaced by the moulded plastic stools created in the 1990s by Singaporean industrial designer Chew Moh-Jin.

1956

1995-07311

Kopitiam workers were not passive wage-earners but active citizens who sought their rights in a collective manner. This union badge is a testament to that spirit.

The relationships between the workers’ union, coffee shop bosses and the government were negotiated through discussions and sometimes through strikes.

The Singapore Coffee Shop Employees’ Union was one of 126 employee unions registered in 1940 when the Trade Union Ordinance came to effect in 1946. It later came under the Singapore Association of Trade Unions (SATU) formed in 1961. Following a two-day strike in 1963, the government de-registered SATU and its 29 affiliate unions, including the Singapore Coffee Shop Employees’ Union.

To see more Union badges in the National Collection, click here.

Acknowledgements

Authors:

Sheryl Lee, Assistant Manager (Cataloguing), Heritage Conservation Centre

Vidya Murthy, Curator, National Museum of Singapore

Content contribution:

Ho Swee Ann, Senior Manager (Cataloguing), Heritage Conservation Centre

Afiqah Zainal, Assistant Manager (Cataloguing), Heritage Conservation Centre

Tejala Rao, Temporary Research Assistant, Heritage Conservation Centre

Chang En En, Temporary Research Assistant, Heritage Conservation Centre

Dave Lee, Photographer, Heritage Conservation CentreAdvice and assistance:

Daniel Tham, Senior Curator, National Museum of Singapore

Tan Pei Qi, Assistant Director (Knowledge & Information Management), Heritage Conservation Centre

Prithivi Raj, Manager (Collections Management), Heritage Conservation Centre

Karen Yap, Assistant Manager (Collections Management), Heritage Conservation Centre

Leon Sim, Assistant Conservator (Objects), Heritage Conservation Centre