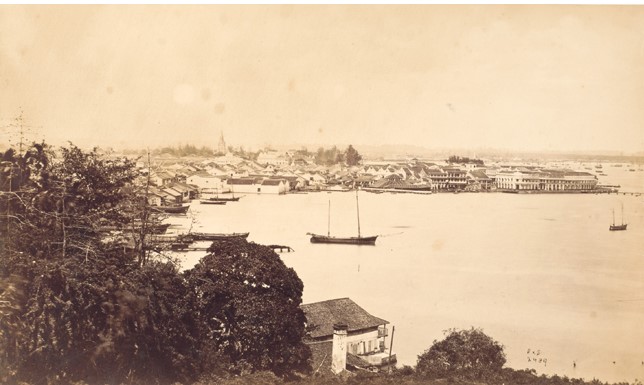

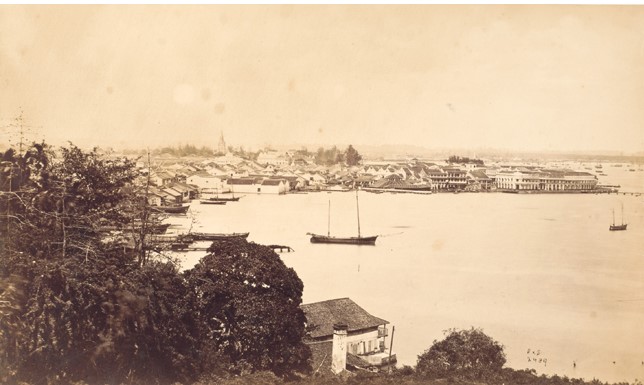

A panoramic picture of Telok Ayer Bay

in 1872 from Mount Wallich by 19th century photographic studio

Bourne & Shepherd.

Squint and you will be able to see

St. Andrew’s Church (later St. Andrew’s Cathedral) and

its spire in the distance as well as Johnston’s Pier on the far right. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

A panoramic picture of Telok Ayer Bay

in 1872 from Mount Wallich by 19th century photographic studio

Bourne & Shepherd.

Squint and you will be able to see

St. Andrew’s Church (later St. Andrew’s Cathedral) and

its spire in the distance as well as Johnston’s Pier on the far right. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

A bay of hopes and dreams

News of the colony’s commercial vibrancy made ripples across Asia. Risking life and limb, immigrants, eager to leave behind impoverished circumstances, embarked on perilous journeys in overcrowded junks for a fresh start in Singapore. Many of the vessels they came on would have docked along Telok Ayer’s seafront.

Upon setting foot on shore, looking for accomodation and job matching assistance would have been a priority, however the religious among them would have likely made a first stop at the makeshift shrines along the waterfront to give thanks for safe passage.

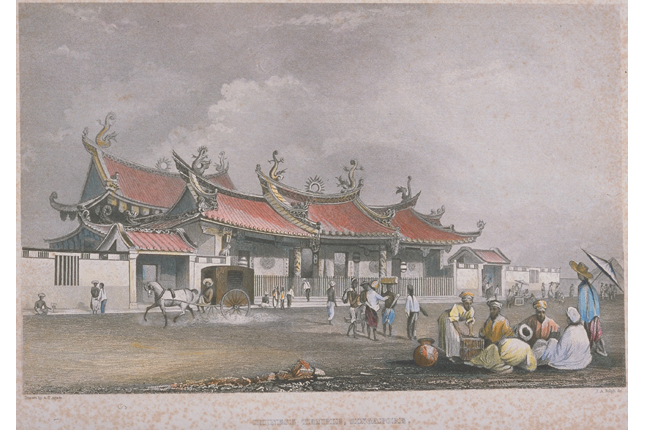

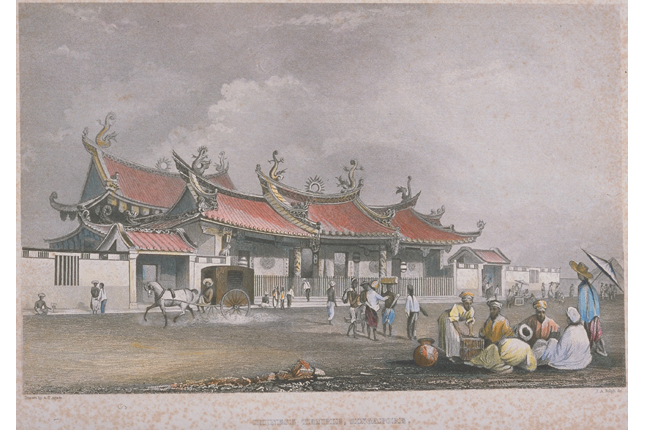

A lithograph of Thian Hock Keng and early settlers along Telok Ayer Street. (c1842. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

A lithograph of Thian Hock Keng and early settlers along Telok Ayer Street. (c1842. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Telok Ayer Bay in the mid-late 19th century. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Telok Ayer Bay in the mid-late 19th century. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

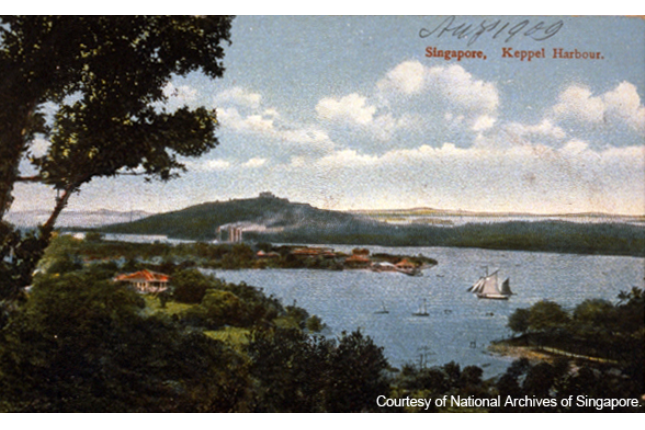

Telok Ayer Basin in and around the 1900s. Its beach was a hive of shipbuilding activity with workers

repairing vessels and piecing together tongkangs (light wooden boats).1 (Image from the Singapore Philatelic Museum)

Telok Ayer Basin in and around the 1900s. Its beach was a hive of shipbuilding activity with workers

repairing vessels and piecing together tongkangs (light wooden boats).1 (Image from the Singapore Philatelic Museum)

Life was pretty rough for immigrants. Telok Ayer itself, which was generally occupied by the Chinese as per the design of the Raffles Town Plan of 1822, soon became overcrowded and a hub for the slave trade.2

The British made some adjustments to the site beginning in the late 1800s via reclamation works which pushed Telok Ayer Street four streets away from the seafront. Cecil Street, Robinson Road and Shenton Way were subsequently built on the reclaimed land.

Even more has changed since then, with the area now home to skyscrapers and modern buildings. Despite these sweeping changes, the imprint of Singapore’s early immigrants still exists in the form of six historic buildings: the Thian Hock Keng temple, Singapore Yu Huang Gong, Ying Fo Fui Kun, the Al-Abrar Mosque, Nagore Dargah and the Telok Ayer Methodist Church. The National Heritage Board gazetted these as national monuments between the years 1973 and 2009, and they remain as tangible representations of our forebears' fears, hopes and dreams.

Join us as we walk you through Telok Ayer’s multicultural, national gems.

Ying Fo Fui Kun, a clan association, strove to help new Hakka immigrants find accommodation and jobs in Singapore. Most Hakkas worked as woodcutters and carpenters as well as blacksmiths and goldsmiths.

Ying Fo Fui Kun, a clan association, strove to help new Hakka immigrants find accommodation and jobs in Singapore. Most Hakkas worked as woodcutters and carpenters as well as blacksmiths and goldsmiths.

Established in 1822, just three years after Stamford Raffles landed, this cosy, two-storey clan provided

Hakka settlers with job matching services and temporary respite3 after the long journey at sea.

Its name reflects its founders’ desire for peaceful coexistence among the Hakkas of Singapore4 — the fourth largest Chinese dialect group. The late founding prime minister Lee Kuan Yew, as well as the Aw brothers of Tiger Balm fame, are among some of Singapore’s most well-known Hakkas.

The monument’s appearance resembles clan-temple buildings common in the southeastern coastal region of Guangdong, China. As you walk by, take note of the windows along its facade for they have been positioned pretty high off the ground to discourage intruders.

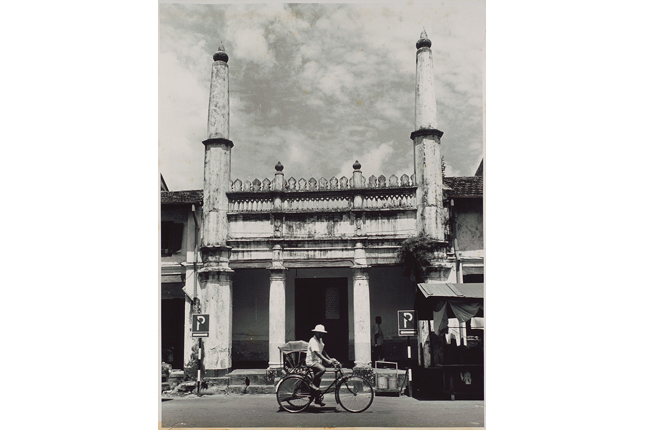

Nagore Durgha when it served as a shrine. It was repurporsed into an Indian-Muslim Heritage Centre in 2011. Its distinct fluted Corinthian pillars set it apart from its neighbours.

(Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Nagore Durgha when it served as a shrine. It was repurporsed into an Indian-Muslim Heritage Centre in 2011. Its distinct fluted Corinthian pillars set it apart from its neighbours.

(Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Walk a little further down the street and you’ll be greeted by the peach and white limestone Nagore Dargah Indian-Muslim Heritage Centre — a replica of an Indian shrine in Tamil Nadu devoted to 13th century Muslim saint Shahul Hamid who was known for his ability to protect sailors and seafarers.

Seeking a new life, Chulia immigrants who worked primarily as traders and money changers, left their homes along the windswept Coromandel Coast in southern India for Singapore. Before embarking on the long voyage, they visited the saint’s shrine in the town of Nagore to pray for safe passage.

The Chulias built a version of this shrine in

Telok Ayer between the years 1828 and 1830.

The building boasts eclectic architecture.

Think Doric columns and arches as well as large French style windows.5

Look closely and you will be able to spot niches in its towers — oil lamps used to be placed in these little lots during festivals. In 2011, it was relaunched as the Nagore Dargah Indian Muslim Heritage Centre.

Just a few doors down stands the former Keng Teck Whay building — the only

surviving Peranakan ancestral hall and clan complex in Singapore.6 It was closed to the outside world for almost 160 years.

Citing a common ancestry in Zhangzhou, in the Fujian Province of China,7 36

Peranakan merchants with surnames such as Ang, Chan and Yeo,8 got together to establish the private mutual aid organisation in 1831.

The building which served as a place to venerate their ancestors,

worship the deity Sanguan Dadi,9 and conduct meetings, was completed in the late 1840s and early 1850s.10

Membership continues to be restricted to the male descendants of its founding members.11

The Keng Teck Whay brotherhood relocated to Changi in 2010

following the structure’s gazette as a national monument the year before.12 The Taoist Mission (Singapore)

acquired it in 2010 and oversaw an elaborate $3.8 million restoration project.

The building now bears a new name — the Singapore Yu Huang Gong and is dedicated to

the worship of the Heavenly Jade Emperor. It is open to all. While there, keep a look out for

delicately crafted sculptures and carvings of dragons, fish and flowers on its roofs.

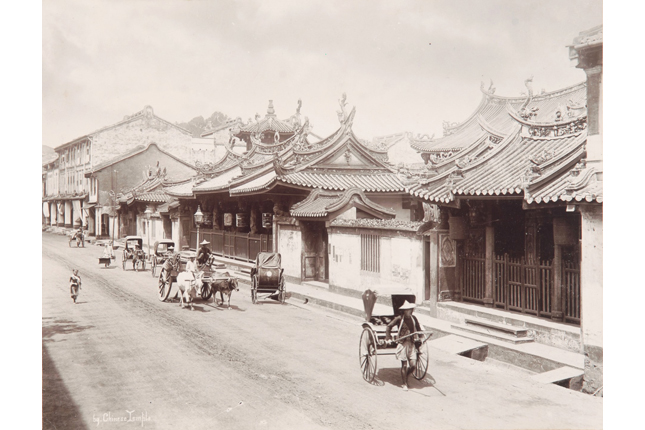

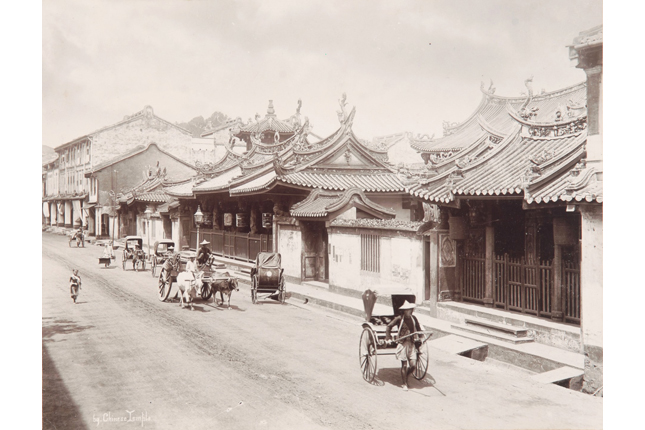

Photographic studio G.R. Lambert & Co.’s

albumen print of the Thian Hock Keng Temple (Temple of Heavenly Happiness)

at Telok Ayer Street in the 1880s. Constructed between 1839 and 1842, the temple

is dedicated to Mazu, a deity widely regarded as the goddess of the sea. The temple, one of

the oldest places of worship in Singapore, was designated a national monument in 1973.

(Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Photographic studio G.R. Lambert & Co.’s

albumen print of the Thian Hock Keng Temple (Temple of Heavenly Happiness)

at Telok Ayer Street in the 1880s. Constructed between 1839 and 1842, the temple

is dedicated to Mazu, a deity widely regarded as the goddess of the sea. The temple, one of

the oldest places of worship in Singapore, was designated a national monument in 1973.

(Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

After a long journey by sea, weary travellers of yesteryear were said to have made their way through Thian Hock Keng’s incense-filled halls to offer thanks to Mazu, a goddess known for her ability to protect seafarers.

Likely the oldest Hokkien temple in the country, Thian Hock Keng at 158 Telok Ayer Street started life as a small shrine for Mazu. It was rebuilt between 1839 and 1842 with the donations of owners and sailors of Chinese junks at the harbour, as well as Hokkien merchants and community leaders.

Engravings of bats, in the corners of carved stone windows along the temple’s facade, represent luck and prosperity.

Inside, a wooden plaque inscribed with Chinese characters which mean “gentle waves over the South Seas” — a blessing for safe passage from Emperor Guangxu of Qing China — takes pride of place above the temple’s main altar.13

Once a year, Thian Hock Keng organises a rambunctious procession known as the Excursion of Peace where a sedan chair ferrying the image of Mazu is paraded through the historic streets of Telok Ayer before proceeding to board a ferry at Marina South Pier to bless the sea.

The temple was refreshed in a major restoration exercise between 1988 and 2000, earning it an honourable mention at the UNESCO Asia-Pacific Heritage Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation in 2001.

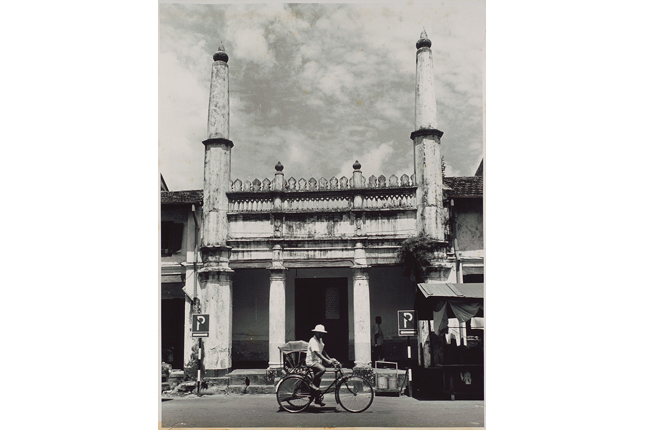

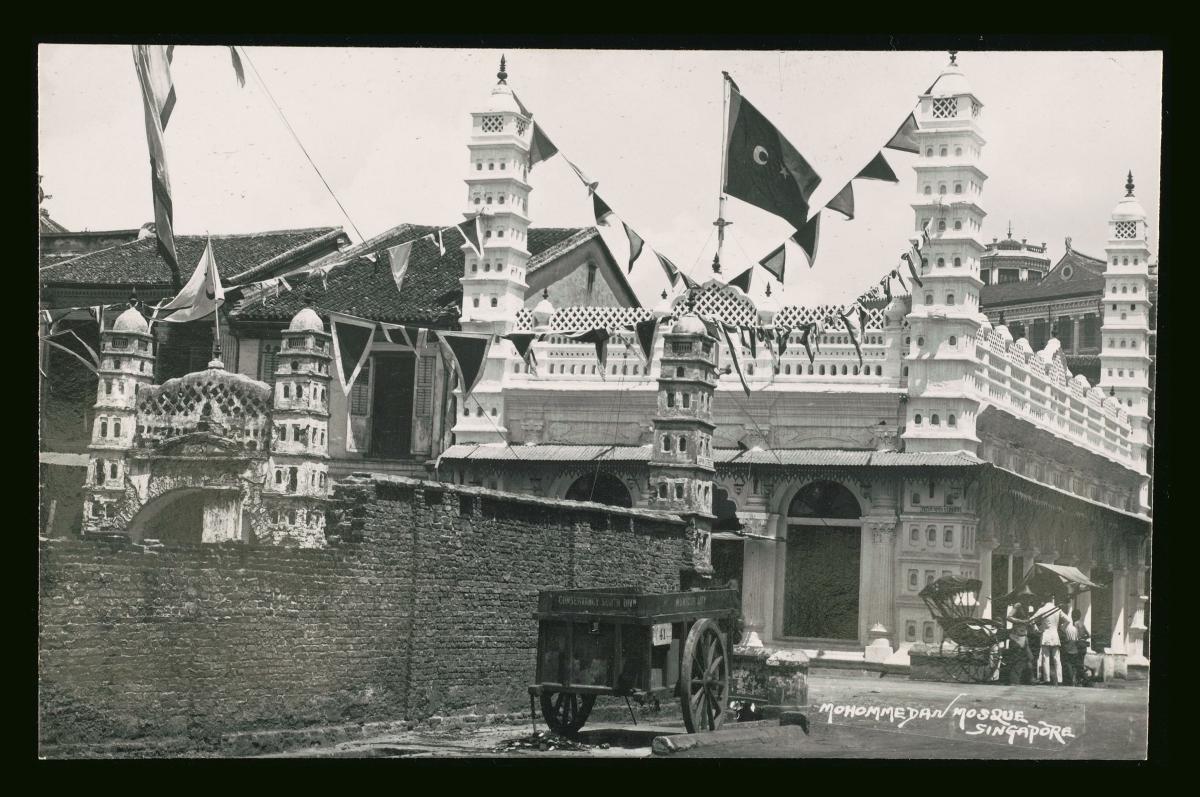

The Al-Abrar Mosque which faces Mecca,

was established in 1827 as a thatched hut which explains its

nickname — kuchu palli, or hut mosque in Tamil.

Between 1850 and 1855, the hut was replaced by a brick

building which still stands today albeit with some modifications.14

(c1950s. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

The Al-Abrar Mosque which faces Mecca,

was established in 1827 as a thatched hut which explains its

nickname — kuchu palli, or hut mosque in Tamil.

Between 1850 and 1855, the hut was replaced by a brick

building which still stands today albeit with some modifications.14

(c1950s. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Continue along the same five-foot way and you’ll spot the Al-Abrar Mosque, also known as Masjid Chulia. The mosque was established as early as 1827 as a place of worship for Chulias or Tamil Muslims from the Coromandel Coast of southern India. It took the form of a thatched hut.

The mosque’s Indo-Islamic design, with features such as minarets at its entrance, stands out from the rows of shophouses lining Telok Ayer. Inside, the mosque boasts European Neoclassical design elements such as Doric columns and French louvred windows.

The mosque stands as a reminder of the role Chulia immigrants played in shaping Singapore as some of the colony’s early traders and money changers.

The exterior walls of Telok Ayer Methodist Church are rather thick, having been

reinforced during World War II to protect hundreds seeking refuge from bullets and shrapnel.

Venture inside and you might be directed to a regular looking female toilet.

During the war, it served as a storeroom with a trap door for women and girls to hide from the Japanese.

The exterior walls of Telok Ayer Methodist Church are rather thick, having been

reinforced during World War II to protect hundreds seeking refuge from bullets and shrapnel.

Venture inside and you might be directed to a regular looking female toilet.

During the war, it served as a storeroom with a trap door for women and girls to hide from the Japanese.

At the end of the street stands the charmingly eclectic

Telok Ayer Methodist Church building, originally founded in 1889 in a shophouse clinic

owned by American Methodist missionary Dr Benjamin West.15 Dr West had a heart for the

Chinese community and his parishioners included patients recovering from opium addiction.16

The church moved to its present day location in 1925. To reflect the make-up of its early congregation, a Chinese-style pavilion roof was installed.