TL;DR

In 2023, Tao Bu Keng Temple celebrated its 103rd anniversary. This old temple, closely connected to the Sungei Tengah village of old, continues to hold its annual Nine Emperor Gods festival, serving as a gathering site for former villagers to rekindle past ties, and build new networks and communities in their relocated site at No. 2 Teck Whye Lane.On a quiet street in Teck Whye Lane within the Choa Chu Kang Combined Temple lies the Tao Bu Keng Temple. However, as the Nine Emperor Gods Festival approaches toward the end of the eighth lunar month, the once peaceful area is transformed into a bustling hub of activity. Former villagers of Sungei Tengah village, along with their families and Choa Chu Kang residents, gather in celebration.

The temple is of great significance to the former villagers, who were relocated to different housing estates due to urban redevelopment. The temple provides them with a valuable opportunity to reunite and serves as a space for old villagers to reminisce about their childhood memories and the kampong lifestyle. This old kampong spirit and unity is rekindled through their devotion to the Nine Emperor Gods.

The Beginning: Sungei Tengah Village

Sungei Tengah village, also known as 东成村 (Dong Cheng Village) in Chinese, is situated between Sungai Tengah River and Sugai Peng Siang River. The village was named after a Chinese trader called 东成 (Dong Cheng) who arrived in the 1800s from Nan’an, Southern Fujian, China. Legend has it that upon settling in Singapore, he sought permission from the British colonial government to develop the land where Sungei Tengah Village was located. As a result, he was known as the “kangchu” or “master of the riverbank”.

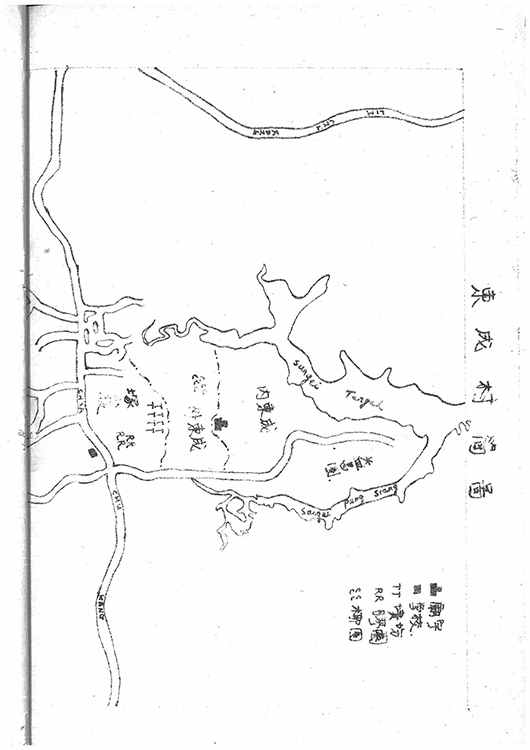

Sungei Tengah Village divided into Wai Dong Cheng, Nei Dong Cheng and Yi Chang Yuan, drawn by the Nanyang University Southeast Asia Chinese History Survey Team (also known as 南洋大学东南亚华人史调查小组 in Chinese)

According to residents who lived in the village in the 1960s, the village was divided into various areas (refer to image above): Wai Dong Cheng (外东成) or “Outer Sungei Tengah village”, Nei Dong Cheng (内东成) or “Inner Sungei Tengah village” and Yi Chang Yuan (益昌园). Villagers accessed the village from Choa Chu Kang Road, 12½ milestone. In the early 20th century, most of the village’s residents hailed from Nan’an and An’xi, in Southern Fujian, China. According to a 1947 population census, the village was home to around 1,383 people, with the majority bearing the surnames Wang(王)and Zhuo (卓). Other common surnames among the villagers included Cai (蔡), Liang (梁) and Hong (洪).

Sungei Tengah Road located on Choa Chu Kang Road, 12 ½ milestone (1980s. Courtesy of Tao Bu Keng Temple.)

Entrance to Sungei Tengah Village on Sungei Tengah Road (1980s. Courtesy of Tao Bu Keng Temple.)

In the early 20th century, the villagers mainly worked in pineapple plantations. Once the pineapples ripened, they were harvested and sold to distributors located on Bencoolen Street. However, by the 1920s, a decline in pineapple prices and soil nutrient depletion from prolonged cultivation prompted the villagers to transition to rubber plantations. Wang Ke Zhao (王可照) and Chen De Tu (陈德土), both from Nan’an, Southern Fujian, China owned two of the largest rubber plantations in the village.

The Japanese invasion of Singapore in 1942 brought about another shift in the village's agricultural landscape, as Japanese soldiers demanded the removal of rubber plantations. Villagers switched to vegetable cultivation to meet the soldiers' needs and address food shortages. Livestock rearing also became common, as it was necessary to fertilize the land for vegetable planting. This practice continued after the war until the depleted soil made vegetable cultivation unviable. Large-scale pig, chicken, and duck farming began to emerge in the mid-20th century.

"My house was located three kilometers from Choa Chu Kang Road. To feed the pigs, we had to cook vegetable feed. The area where I lived was close to the sea and the vegetables that were used to make the feed did not grow nearby. Therefore, I had to visit my neighbours house every day to collect the vegetables. They had a pond suitable for growing these vegetable feeds and the neighbours were kind and helpful. We supported each other. When it was time to prepare the chickens for sale, the entire family would come and help us. In turn, we would also help them when needed.”

Ng Hock Huat, Interview conducted by National Archives of Singapore in 2017

The Village’s Communal Hub

Situated on the border of Nei Dong Cheng and Wai Dong Cheng were five temples: Tao Bu Keng Temple, Ling Jin Tang (灵晋堂), Shui Gou Guan (水沟馆), Jin Shui Guan (金水馆), and Lai Sheng Gong (来圣宫). Tao Bu Keng Temple, along with the other temples in the village, served various functions, from providing spiritual support to being the focal points for the daily communal activities in Sungei Tengah village.

Row of five temples (1980s. Courtesy of Tao Bu Keng Temple.)

Tao Bu Keng Temple had humble beginnings dating back to 1920. It was initiated by a 23-year-old fisherman named Cai En (蔡恩) who lived in Yi Chang Yuan. While fishing, he discovered an incense censer and dreamt that it belonged to the Nine Emperor Gods. Inspired by this, Cai En, along with a few acquaintances, brought the urn home and began to observe the Nine Emperor Gods Festival in his home. As the number of devotees grew, Cai En decided in 1945 to construct a temple in the village to house the censer. With the support of the community, Cai En identified the location, and villagers came together to donate money and manpower to build the temple. The structure initially started as a simple attap house before being rebuilt into a temple made of zinc and tiles.

Tao Bu Keng Temple in Sungei Tengah village (1980s. Courtesy of Tao Bu Keng Temple.)

An altar to the Tiger God in front of Tao Bu Keng Temple (1980s. Courtesy of Tao Bu Keng Temple.)

Interior (Top) and entrance of Tao Bu Keng Temple (Below) (1980s, Courtesy of Tao Bu Keng Temple.)

The temple has served the community in various ways in different times. Prior to the Second World War, festivals held in the temple were used to raise funds for the anti-Japanese war efforts in China. For example, Cai Wen School and Dong Chen School raised a total of $101 for the Singapore Overseas Chinese Relief Fund Committee through the sale of flowers during the annual Nine Emperor Gods Festival held in the temple. The temple’s opera stage was an important venue for entertainment and also temporarily housed the Nam San Public School in 1945 while the school building was being built.

Tao Bu Keng Temple’s opera stage (1980s. Courtesy of Tao Bu Keng Temple.)

Hokkien opera performances (1980s. Courtesy of Tao Bu Keng Temple.)

The annual Nine Emperor Gods Festival, celebrated at Tao Bu Keng Temple, held great significance as a communal event in Sungei Tengah Village. Embracing the kampong spirit, both young and old villagers would congregate at the temple from the eighth month of the lunar calendar to prepare for the festival. This involved cleansing the exterior and interior of the temple, as well as changing the decorations. Children played a role in clearing procession routes by picking up rocks and lighting the way with kerosene lamps.

The receiving ritual occurred on the last day of the eighth lunar month, taking place in the 1970s at a jetty near Lim Chu Kang. Upon completion of the receiving ritual, a grand procession would wind through the surrounding villages over three to four hours, featuring palanquins, drum troupes, and mediums. Villagers would line the streets, kneeling to seek blessings from the passing mediums, while some families set up tables of offerings for the deities to bless their households.

Festive celebration at Tao Bu Keng Temple in Sungei Tengah village (1990s. Courtesy of Tao Bu Keng Temple.)

Procession held at Tao Bu Keng Temple in Sungei Tengah village (1980s. Courtesy of Tao Bu Keng Temple.)

Decorated trucks and incense sticks used in Tao Bu Keng Temple (1980s. Courtesy of Tao Bu Keng Temple.)

Another significant event during the Nine Emperor Gods festival that brought the villagers together occurred during the eighth and ninth day of the ninth lunar month, during which 50 to 60 tables of vegetarian dishes were prepared by the villagers and laid out in front of the temple as an offering to the Nine Emperor Gods. Villagers used shoulder poles to carry the vegetarian dishes from their homes to the temples, and some even utilized nearby rivers to transport their offerings by boat. The Nine Emperor Gods, through their mediums, would walk around to bless the offerings. At the conclusion of the rituals, the villagers would come together to partake in the feast prepared for the occasion.

"The vegetarian banquets were attended by the villagers…after the burning of the incense paper, everyone can eat...the villagers would wait for the signal from the committee before starting to eat…clutching their own pair of chopsticks, everyone would move from table to table, partaking in the shared feast.”

Mr Chua, former resident of Sungei Tengah Village

The Nine Emperor Gods festival also featured Hokkien opera performances, which were a beloved highlight for the villagers. These performances took place on the eighth, ninth, and tenth days of the festival as expressions of gratitude to the deities. For the villagers, these opera performances were a rare source of entertainment in the village. Renowned opera troupes such as Xin Sai Feng and Fei Yan took the stage, presenting Chinese classics such as "Five Tigers Conquer the West" and "The Legend of the White Snake." Villagers gathered in front of the stage to watch the performances, and there were even stalls set up that sold an array of snacks to the audiences.

The Relocation

In 1958, the land on which Sungei Tengah village was situated was earmarked for resettlement to make way for developments such as the Kranji reservoir and the extension of Tengah Airbase. As a result, villagers were resettled, with those living in Yi Chang Yuan being the first to be relocated, followed by others. The villagers were dispersed to different housing estates in Choa Chu Kang, Bukit Panjang, and Jurong East. Additionally, Tao Bu Keng Temple was shifted to No. 2 Teck Whye Lane and became part of a combined temple complex called the Choa Chu Kang Combined Temple, which officially opened in 1996.

Choa Chu Kang Combined Temple (2017. Courtesy of Nine Emperor Gods Festival Documentation and Research Project.)

The Annual Reunion

Even after the disappearance of Sungei Tengah village, the villagers maintained their strong ties by reuniting at Tao Bu Keng Temple every year to participate in the Nine Emperor Gods festival, which continued to be held at the temple’s new location. Former villagers would use this opportunity to catch up with old neighbours and friends as they helped out in the temple. Groups of old friends would gather at the multi-purpose hall and the temple's front yard to socialize and share nostalgic memories over a spread of curry vegetables, bee hoon, and crispy fried tau kwa, generously provided by the temple.

Today, the temple actively keeps the memory alive by organising yew (游 in Hokkien) kampong events every few years. During these events, temple representatives, accompanied by mediums and palanquins, revisit the jetty off Lim Chu Kang, which was previously used to receive the Nine Emperor Gods at Sungei Tengah village. A “inviting water” ritual is conducted there, serving as a poignant reminder of their roots and history. The tour also includes a visit to an old temple, Ci Bei Ma Zu Gong (慈悲妈祖宫), to pay respects, re-enacting the tradition of the receiving procession paying their respects at Ci Bei Ma Zu Gong during the receiving ceremony. This event holds significant historical and cultural importance.

Water is brought back from the old receiving site to the temple (2010s. Courtesy of Nine Emperor Gods Festival Research and Documentation Project.)

Paying respects at the temporary altar set up by Ci Bei Ma Zu Gong (2010s. Courtesy of Nine Emperor Gods Festival Research and Documentation Project.)

The tradition of the vegetarian feast persists at the new site to this day. Former villagers continue to arrange tables of vegetarian food, tea, and incense on the grounds of Tao Bu Keng Temple for the Nine Emperor Gods. The Nine Emperor Gods’ mediums visit each table to receive tea and offer guidance to the head of the household. Following the ceremony, the food on the tables is shared among all. This practice has become a meaningful way for former village residents to reconnect and enjoy a communal meal together.

Conclusion

The relocation of Sungei Tengah village and Tao Bu Keng Temple has not diminished the enduring connections and bonds among former residents. Through the annual celebration of the Nine Emperor Gods festival, the temple continues to serve as a unifying force, fostering unity among people from diverse backgrounds, bridging the old kampong villagers with the new communities in the Choa Chu Kang area.

The author would like to thank Tao Bu Keng Temple and Nine Emperor Gods Festival Documentation and Research Project for the photo contributions, as well as Esmond Soh for reviewing the article.

Notes

-

1. Koh, Keng We, Lin, Chia Tsun, Koh, Kah Wee Ernest, Lim, Yinru, and Soh, Chuah Meng Esmond. The Nine Emperor Gods Festival in Singapore: Heritage, Culture and Community, two vols. Singapore: Nine Emperor Gods Project, Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre, 2023.

2. Lin, Chia Tsun and Koh, Keng We. Sacred Ties: A Century of Devotion to Nine Emperor Gods in Tao Bu Keng Temple. Singapore: Tao Bu Keng Temple, 2023.

3. Malaya, comprising the Federation of Malaya and the Colony of Singapore: A report on the 1947 census of population. London: Governments of the Federation of Malaya and the Colony of Singapore by the Crown Agents for the Colonies, 1949

4. 南洋大学东南亚华人史调查小组, 蔡厝港东城村村史调查,新加坡,南洋大学史地系,1969.