The Nine Emperor Gods Festival

The Nine Emperor Gods Festival (九皇爷诞) is an important religious event in the Chinese lunar calendar in Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand. Starting from around the end of the eighth lunar month to the ninth or tenth day of the ninth lunar month, the Nine Emperor Gods Festival lasts for at least nine to ten days, and involves a personal regime of abstinence for the devotees and practitioners alike. The scale and duration of the Nine Emperor Gods festival in Singapore is different from other Chinese deity festivals in Singapore and other parts of Southeast Asia, but also differs from the same festival in China.

While some believe the festival to have its roots in ancient Chinese cosmology and religion, centering on the propitiation of the Northern Dipper in Taoism and Buddhism for longevity and salvation from disasters and misfortune, there are other stories in Singapore and Southeast Asia about the origins of the Nine Emperor Gods and who they are (or who he is), which reflect the historical experiences of the Chinese in Southern China and Southeast Asia. Some describe the gods as being pirates who robbed the rich to give to the poor. Some believe that they are Ming loyalists, while others believe the Nine Emperor Gods to be the last Ming Emperor as well as Zheng Chenggong, a pirate leader during the late Ming dynasty and opponent of the new Qing government in China in the mid-seventeenth century.

Geographic Location

In Singapore, there are numerous temples hosting the Nine Emperor Gods Festival each year. They are located across the island. The two oldest temples hosting the celebrations, being more than a hundred years old, are the Hougang Dou Mu Gong (Tou Mu Kung) (后港斗母宫) and the Feng Shan Gong (Hong San Keong) (凤山宫) respectively.

The others, include Choa Chu Kang Dou Mu Gong (蔡厝港斗母宫), Jing Shui Gang Dou Mu Gong (汫水港斗母宫) , Kim San Tze (金山寺), Jiu Huang Gong (九皇宫), Jiu Huang Dian (九皇殿), Long Nan Dian (龙南殿), Long Nan Si (龙南寺), Long Shan Yan Dou Mu Gong (龙山岩斗母宫), Nan Shan Hai (南山海), Temple, Shen Xian Gong (神仙宫), Xuan Wu Shan (玄武山), Yu Hai Tang Guan Yin Tang (玉海棠观音堂), Yu Huang Gong (玉皇宫), and Zhun Ti Tang (准提堂). In more recent years, there have been new organisations or temples holding the Nine Emperor Gods festival, such as Nan Bei Dou Mu Gong (南北斗母宫) and Yu Huang Gong (玉皇宫) respectively.

Communities Involved

Many of the older Nine Emperor Gods temples were centred on local and regional communities, family networks or the charisma of leaders and ritual experts for their festival. Some of these temples had to rebuild their communities after moving to new locations or after having their surrounding communities relocated to new residential areas. Nevertheless, the nature of the festival, with its emphasis on a strict vegan regime and on personal abstinence and purity, meant that it has transcended locality or Chinese sub-ethnic communities.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

The Nine Emperor Gods are represented in different ways. In some temples, there is just a single tablet with the characters stating Nine Emperor Gods (九皇大帝). In other temples, they are represented in the form of a statue, representing the first or second Emperor, or in the form of nine statues representing each of the Nine Emperors.

Furthermore, some temples have spirit mediums representing for the Nine Emperor Gods while others do not. There are temples with one spirit medium for the Nine Emperor Gods, as well as one, the Choa Chu Kang Dou Mu Gong, which has nine mediums representing each of the Nine Emperor Gods. The rituals and priests involved also vary, with Taoist priests predominantly from the Zheng Yi tradition, while there are some temples using the Quanzhen tradition. In temples with a Buddhist bent, they have their own ritual specialists, and in one of them, they also use Buddhist monks for their rituals.

The key rituals are the receiving and sending-off ceremonies for the Nine Emperor Gods. These take place mainly by the sea, or in earlier times, along rivers and canals. Present-day sites for the receiving and sending off include East Coast Park, Changi Beach, and Punggol Marina. While not all temples receive the gods on the same day or time, all of the temples send off the Nine Emperor Gods on the ninth day of the ninth lunar month. Most of the receiving and sending off take place at night, although there are some temples which do this in the day, like Jiu Huang Gong in Arumugam Road.

Another important aspect of the festival is the emphasis on purity. Thus, at each temple, spring-cleaning is done at least two weeks before the festival. Assistants helping out in the festival, especially in the key rituals, have to start their vegan diet early and follow strict rules. This involves abstaining from meat, eggs, milk, and even garlic and onions. Likewise, devotees have to follow these rules during the festival, with some opting to start as early as a month or more before the festival. During the festival, temple helpers and devotees are dressed in white or yellow shirts and pants. They wear white handkerchiefs over their heads and yellow strips of cloth around their waists and wrists. Yellow and white both represent purity, while there are people who believe that the white also signified mourning. In some of the temples, the red lanterns are replaced by yellow lanterns or candles.

The ritual of the festival is the raising of the nine lamps (九天灯), which marks the start of the festival. This is usually done on the day of the receiving of the Nine Emperor Gods. Nine kerosene lamps are raised on long bamboo poles either before or after the receiving of the Gods. In more recent times, some temples have started using wood and steel poles because of the difficulty of finding and obtaining bamboo poles. The lamps are lowered, cleaned and refilled twice each day, once at about 5am before the rising of the sun, and the second time, at about 5-6 o’clock in the afternoon, before the setting of the sun. To mark the end of the festival, these nine lamps are lowered on the tenth day, after the sending off of the Nine Emperor Gods.

Another event is the yew keng (Hokkien for the Chinese term 游境) or procession. While this started out in earlier decades as a tour of the surrounding kampong neighbourhood, the term has now come to mean the visiting of other temples. The exchange of visits by different temples in the Nine Emperor Gods network has created an identity among these temples.

The palanquins of the Nine Emperor Gods are special in that they are fully covered, with the interior kept from view either by doors or curtains. During key rituals, important ritual objects are carried into or out from the palanquins under the cover of flags or shielded by people. It is done as a mark of respect to the Nine Emperor Gods. All the other palanquins are carried by men. A colourful recent development among some temples is the decoration of the palanquins and sedan chairs for the Nine Emperor Gods with neon lights, used in the receiving and sending-off processions, as well as in the yew keng processions. In some temples, they have also introduced the Dou Mu sedan chair, which is the only chair carried by women.

Another interesting feature of the festival would be the dragon ship, called long chuan (龙船), or the ritual ship (法船). These ships are made of paper and are filled with salt, oil, rice, incense paper, joss sticks, and other items before being sent out and burnt at sea during the sending-off ceremony. In most temples, devotees are allowed to write their names or the names of their family members and paste them on the ship, symbolising the sending out and eradication of their bad fortune to the sea.

Present Status

The Nine Emperor Gods Festival is more than ancient cosmology and rituals. The festival is about the temples and the communities they are embedded in. The celebrations of the festival reflect how temple communities have transformed as they align themselves to Singapore’s changing socio-cultural and economic landscape. The rituals are also evolving with time. For example, LED lights are used on some of the sedan chairs, while new rituals are also added in as a result of overseas influences, such as the practices from Taiwan. For the temple communities that continue to actively celebrate it, the Nine Emperor Gods Festival is an invaluable part of their living heritage.

References

Reference No.: ICH-055

Date of Inclusion: March 2019

Content Contribution

Nanyang Technological University (NTU) History Programme

Principal Investigator: Assistant Professor Koh Keng We

Co-Investigators: Professor Kenneth Dean, Professor Choi Chi Cheung, Dr. Hue Guan Thye

Collaborators: Professor Kaori Fushiki, Assoc. Assistant Professor Terence Heng

Team leaders: Lee Chih Hsien, Lin Chia Tsun, Dean Wang, Lim Ke Hong, Jack Chia

Students Involved: Nanyang Technological University (NTU), National University of Singapore (NUS), Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA)

Cheu, Hock Tong. Analysis of the Nine Emperor Gods Spirit-Medium Cult in Malaysia. Ithaca, N.Y, Cornell University, 1982.

Cheu, Hock Tong. “The Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods in Malaysia: Myth, Ritual, and Symbol” Asian Folklore Studies 55, (1): 49-72, 1996.

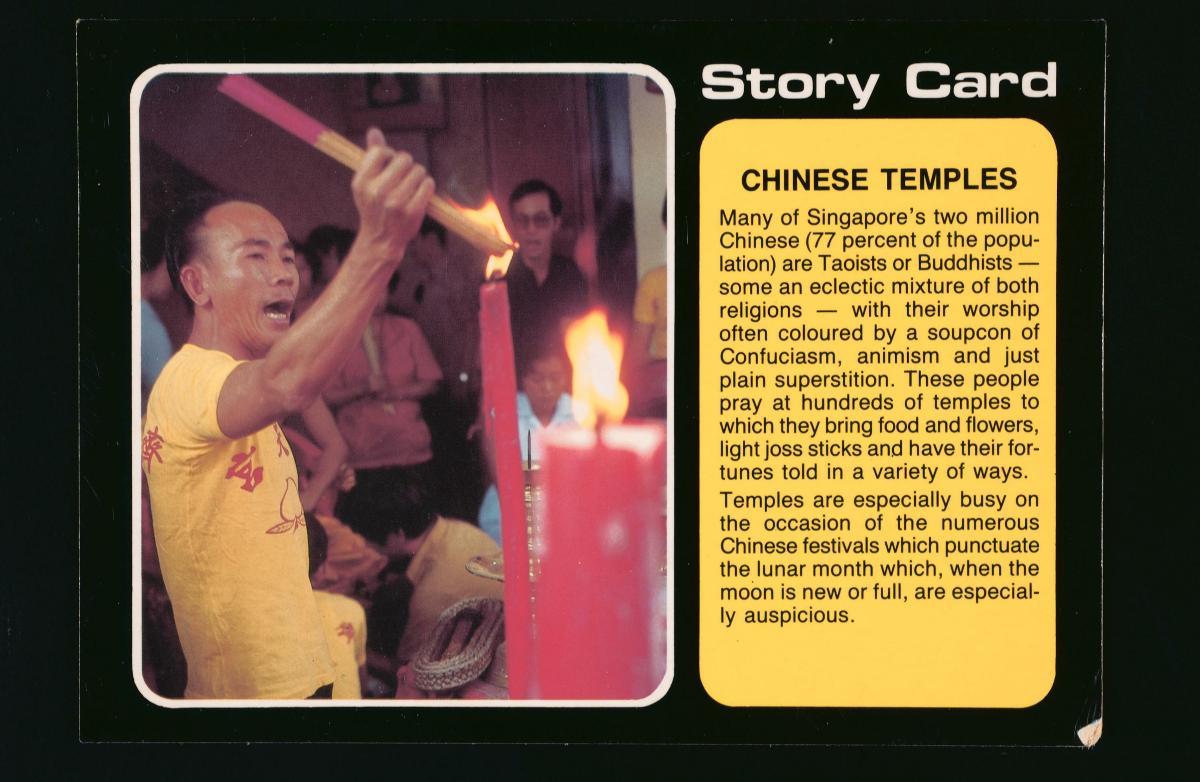

Comber, Leon. Chinese Temples in Singapore. Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 1958.

DeBernardi, Jean Elizaebth. Penang: Rites of Belonging in a Malaysia Chinese Community, Singapore: NUS Press, 2009.

Elliott, Alan John Anthony. Chinese Spirit-Media Spirit-Medium Cult in Malaysia. London: Royal Anthropological Institute, 1955.

Heinze, Ruth-Inge. “The Nine Imperial Gods in Singapore” Asian Folklore Studies 40 (1): 161-65, 1981.