Text by Marcus Chua

Images by Marcus Ng and Marcus Chua

BeMuse Volume 4 Issue 1 - Jan to Mar 2011

Amid the undergrowth of a lush green forest, the diminutive mousedeer twitched its nose as it picked up a foreign scent. It sensed danger and bounded away in a series of elastic leaps. Nearly tripping over a sleeping python, it regained its composure but turned around to see the yellows eyes of a tiger towering over it. With a terrifying roar, the magnificent beast threatened to devour the mouse deer.

Thinking quickly under pressure, mousedeer said, “Oh tiger, before you are entitled to eat me, please let me finish my task. I was asked by the king to keep watch over his belt before he returned so that no one would wear it.”

Puzzled at its demand, tiger demanded to see the belt of the king.

“There it is,” said the mousedeer, pointing to the intricately patterned sleeping coil beside it. “But you must not touch or wear it.”Piqued by its beauty, the tiger was mesmerised and had the yearning to wear the belt for himself. Ridding all hostile intentions, the tiger requested, “Mousedeer, could you lend me the belt for a second, only a second?”

Mousedeer disagreed at first, but relented on the condition that no one must know that it lent tiger the king’s belt or it would be in great trouble.

The tiger agreed and waited for the mousedeer to get away, then picked up part of the large snake and wrapped it eagerly around its waist. Rudely awoken and incensed, the python tightened and threw its coils around the tiger till it could hardly breathe. Safe in a distance, the mouse deer had its last laugh.

This old Malay folklore could well have taken place in Pulau Ubin where such wildlife once flourished. In the rolling virgin forests of the boomerang-shaped island northeast of mainland Singapore, once roamed the three animal characters of this story as well as numerous other land animals, birds, fish and invertebrates. Other notable resident fauna included the now possibly nationally extinct cream-coloured giant squirrel (Ratufa affinis) and sambar deer (Rusa unicolor).

These creatures co-existed and were probably hunted by stone-age people and ancient civilisations that settled on Pulau Ubin. Neolithic stone tools, quartz flakes, clay and stoneware artefacts unearthed from the island by archaeologists are testament to the rich and untold history of the island.

Tigers – Fabled Antagonist, Real Life Victim

The other protagonist of the Sang Kanchil story, the tiger (Panthera tigris) used to be “still over-plentiful in Singapore” in 1895, according to H. N. Ridley, the former director of the Botanic Gardens.

Tigers were said to have swum from Malaysia via Pulau Ubin and the neighbouring island of Tekong to breed on the main island and raise their cubs. It is therefore not surprising that stories of tigers on Pulau Ubin have become told as legends on the island even today.

In one such story, a tiger entered a hut situated along a forest edge. It walked over ashes of a fire, left its mark and finding nothing of interest, broke through the flimsy wall of the hut and went away. The next night, four tigers entered another house nearby, probably looking for a meal of the owner or his dog. The house was left to the tigers as the occupants fled by breaking though the back of the house.

Although feared for its strength and frequently portrayed as the bully in folklore, the king of the jungle did not enjoy its status for long in Singapore. Faced with the loss of habitat to plantations, they turned to humans as food and killed an average of one human being a day. The tiger became a victim of its own fearsome reputation and due to resultant human-tiger conflict the big cats were eventually hunted to national extinction around 1930.

However, tiger sightings were still reported up to the 1950s. In 1997, rumours of a tiger in Pulau Ubin led the police to issue a public advice to keep away from the island. The presence of the tiger was never confirmed and was thought by conspiracy theorists as a ruse by villagers to teach bumboat operators a lesson for raising boat fares!

The Greater Mousedeer: A Tale of Loss and Rediscovery

The diminutive greater mousedeer (Tragulus napu) is a nocturnal forest-dwelling hoofed animal about the size of a large rabbit (shoulder height 30- 35 cm; head body length 52-57 cm). It has features similar to both deer and pigs, and like the former, feeds on fallen fruits and vegetation and has a four-chambered stomach for digestion. However, like pigs, it lacks antlers and has elongated canines, especially in males and hence, is not a true deer. The greater mousedeer is native to Singapore and can also be found in Southeast Asia and Borneo.

Image by Marcus Chua.

Mousedeer used to be fairly common in Singapore before the 1920s but they faced threats such as the loss of their forest habitat and hunting. In Pulau Ubin, the greater mousedeer was recorded based on a single specimen (ZRC.4.4750) collected in 1921 and deposited in the Zoological Reference Collection of the Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research. Other than two other specimens from the mainland collected in 1908 and 1923, no confirmed record of the species existed in the wild for the rest of the century and they were thought be nationally extinct.

A re-introduction effort for the species on the mainland was made between 1998 and 1999, but released animals were not recorded again after 1999.

Compared to the lesser mousedeer (Tragulus kanchil), which are still present on Singapore island in small numbers and distinguished by their smaller size (shoulder height 20-23 cm; head body length 40-55 cm), throat and coat markings (see Low et al, 2009), the greater mousedeer appeared to be gone from the wild forever.

A twist of fate happened in 2008 when the greater mousedeer was rediscovered in Pulau Ubin during a faunal survey of the island. They appear to be fairly widespread across the island and could have come from a latent population that has recovered in numbers or swam from Malaysia. Both adults and young were seen, indicating that a breeding population exists.

Several possible reasons could have led to the return of the greater mousedeer. First, their reappearance in the forest in numbers is a sign that the regenerating forests of Pulau Ubin are once again able to support the existence of these forest dependent creatures. Second, the decrease in human activity on the island after quarries were closed and many villagers relocated probably provided a less disturbed landscape for the animals to thrive. Thirdly, the mousedeer could have swum from Johor, Malaysia, just as how wild pigs and elephants have made the Johor Strait crossing. Finally, as large mammalian predators such as tigers and leopards are extinct on the island, there is reduced predator pressure on the island which could increase their chance of survival.

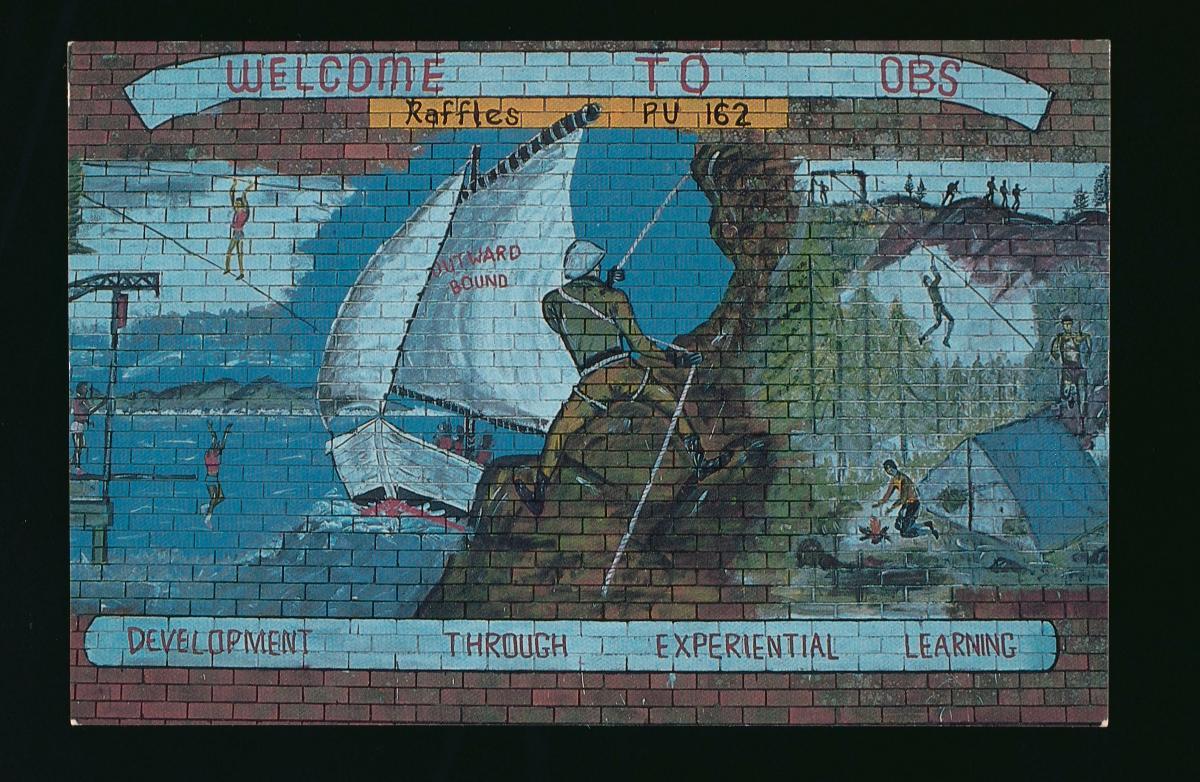

Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Although they have almost literally have come back from the dead, greater mousedeer and mammals on Pulau Ubin still face possible threats outlined in the main story.

However, there is potential for the greater mousedeer to continue to co-exist with man on the island due to the activity pattern of the two groups. Most mammals on the island, including the greater mousedeer, are nocturnal, while majority of human visitors to the island come in the day and do not stay overnight. Hence, it suggests that mammal use of the island is temporally separated from human activity. Additionally, visitorship to the island is higher during the weekends compared to the weekdays. Wildlife on the island may therefore be less disturbed during the relatively quiet periods at night and on weekdays. If well managed, this cyclical difference in activity between wildlife and humans may allow Pulau Ubin to function as both a recreational area for the public as well as a wildlife refuge in the long term and help to ensure the continued existence of the greater mousedeer and other nocturnal wildlife on Pulau Ubin.

Blasts from the Past

The landscape of Pulau Ubin changed, however, following mass human settlement in Singapore. The granite hills of Pulau Ubin (in Malay: Pulau = island, Ubin = granite) were viewed as a valuable resource in building and construction and were extensively quarried from the mid-19th century. Nature made way for man and its machines and deafening blasts could be heard across the island as dynamite was used to blow up and extract granite deposits.

Plantations and aquaculture also changed the island’s landscape. Much of the land was cleared for growing rubber, durian, coconut and other crops. Stretches of mangroves were also cleared for aquaculture. Charming mangrove swamps were replaced by unsustainable and pollutive prawn ponds.

As a result, much of Pulau Ubin’s original natural heritage was destroyed or disappeared. The land was irreparably scarred and original habitats were lost. Naturalists who ventured onto the island found it to be depauperate of its flora and fauna. Lost and gone were the steep, rolling hills covered with primeval forest as well as many of its inhabitants, including the tiger. These are likely to be lost forever.

A Natural Renaissance

In the late 1990s, when the last of Pulau Ubin’s quarries ended their operation, many villagers relocated to the mainland. Slowly, nature recovered and started reclaiming the island like a lost child, spreading its seeds and allowing pioneer grasses and herbaceous plants to take over the fractured landscape. In the untended orchards and plantations, wild plants took root between what remained of commercial crops. This was the dance of natural succession.

As human disturbance reduced and habitats gradually reverted to the wild state, fauna returned. Among the first were birds, which also brought in and dispersed more seeds, aiding in the forest regeneration. Once extinct in Singapore, the oriental pied hornbill (Anthracoceros albirostris) made a comeback on Pulau Ubin and has successfully re-established a population on the island.

Larger animals such as wild pigs (Sus scrofa), which were extinct on the mainland, also made their way by swimming across the narrow Johor Strait from Malaysia and re-colonised the island.

Even an elephant once attempted the straits crossing, but was escorted back to Malaysia after a brief stay on the island. These visits highlighted the potential of Pulau Ubin as a wildlife refuge as habitats on the island became more hospitable to wildlife.

In 2001, plans were announced to develop parts of Pulau Ubin, which included the reclamation of the eastern coast of the island. Ironically, these plans led to the serendipitous discovery of Chek Jawa wetlands by the local naturalist and scientific community. Chek Jawa is a wonderful rich mosaic of ecosystems containing a vast seagrass lagoon, healthy mangrove swamps and a diverse shoreline of sandbars, coral rubble and rocky formations at the southeastern tip of the island.

Word spread and the place quickly made a name for itself as a must-see location among nature lovers and even the general public, which flocked to Chek Jawa in the thousands.

Some would say Chek Jawa was almost loved to death by the unregulated visitor traffic that trampled on many of the marine creatures such as sea anemones and sea stars. But this widespread exposure to the unspoiled beauty of Chek Jawa was also what helped save the wetlands. Struck by the natural wealth of the place and incredible biodiversity, both cityfolk new to their natural heritage as well as the nature community rallied together and appealed to the government for Chek Jawa to be saved for posterity.

A turning point for local nature conservation and community involvement came in December 2001, when the Singapore government announced that reclamation of the island would be deferred for a decade. The National Parks Board (NParks) then took over the management of the area and developed infrastructure such as an elevated boardwalk above the shore to regulate visitor impact to the fragile ecosystems.

Pulau Ubin Today

Today, Pulau Ubin is one of Singapore’s few remaining wild frontiers and among our last rural places. To reach the island, most members of the public take a 10-15 minute bumboat ride from Changi Village and get off at the island’s village, where less than 100 families live in kampong houses without piped water and electricity. Instead, the villagers rely on noisy generators for electricity and wells for water. Life on the island is a throwback to Singapore in the 1960s.

Beyond the village, after years of recovery and natural succession, Pulau Ubin has become a veritable patchwork of viable habitats. Secondary forest (a term used to describe forests that regenerated on land previously used for agriculture or timber) occupies approximately half the island’s land area, while a fifth of it is covered by some of the most extensive mangroves left in Singapore. Small areas of grassland and beach vegetation dot the island, offering variety. The coast is likewise covered with a range of sandy, muddy and rocky beaches.

Endowed with a wide assortment of habitats, the island plays host to an amazing range of biodiversity. Over 600 species of plants are found on Pulau Ubin, including the Bakau Mata Buaya (Bruguiera hainesii), an internationally critically endangered mangrove tree. The island is also much loved for its impressive bird life with at least 177 species of native and migratory species recorded. It remains one of the strongholds of the straw-headed bulbul (Pycnonotus zeylanicus), a large songbird that is imperilled by its own rich and melodious singing due to demand by the cage bird trade, and red jungle fowl (Gallus gallus), the wild ancestor of the domestic chicken. Other than birds, Pulau Ubin’s diversity of mammals, fish, herpetofauna (reptiles and amphibians) and invertebrates is equally stunning for a small island.

A Fairytale Ending?

In spite of the good news, possible threats to the island’s natural heritage are still present. Pulau Ubin receives relatively high visitorship, especially during weekends, and human disturbance of wildlife could be an issue. Other potential threats include poaching and feral dogs. A proposal to set up an energy grid on the island could bring about street lights, and their placement and usage will have to be properly planned and managed to avoid affecting the activity of nocturnal fauna on the island. Our growing population is also placing constraints on housing on the mainland and offshore islands such as Pulau Ubin may be seen as a land bank for future development which can threaten to erase the island’s natural and human heritage.

Still, no matter how grim and even faced with the odds, Pulau Ubin continues to surprise us with its little secrets. While it was thought that the clearing of forests would eradicate forest species, especially mammals sensitive to disturbances, the greater mousedeer (Tragulus napu) was rediscovered on the island in 2008 by the author and NParks during a study of medium-sized mammals of Pulau Ubin. It is an encouraging sign that nature is on the road to recovery as even the greater mousedeer, which had not been seen for more than 80 years and was presumed to be nationally extinct, returned. Other notable fauna recorded during the year-long study include the Sunda pangolin (Manis javanica), common palm civet (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus), long-tailed macaque (Macaca fascicularis), wild pig (Sus scrofa), barred eagle-owl (Bubo sumatranus) and large reticulated pythons (Broghammerus reticulatus). Coming full circle, it is comforting to know that at least the mousedeer and python of the Malay folklore still remain.

While we celebrate the miracles of life, there is a need to understand the practicalities of what can be achieved. It is unlikely that Pulau Ubin can ever be restored to its former natural glory. Nevertheless, there is a need to carefully manage and protect what is left. In order to retain our natural heritage on Pulau Ubin, it is necessary to ensure the co-existence of humans and nature. This will require the joint effort of the public as well as stakeholders who appreciate the importance of this shared treasure. Through research and conservation efforts on the island, scientists, NParks and the community can do their part to preserve its natural heritage. With judicious land use planning and the government’s assurance that Pulau Ubin will be kept in its present state for as long as possible, there is hope that Pulau Ubin will remain Singapore’s urban Eden for time to come.

About the Author

Marcus Chua is a graduate research student of the Systematics and Ecology Lab, Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore. His current research looks at the ecology and conservation of leopard cats and other native mammals in Singapore and is supported by the Wildlife Reserves Singapore Conservation Fund.