By David Chew, Assistant Curator - Singapore Art Museum

Images: Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo Collection

BeMuse Volume 3 Issue 4 - Oct to Dec 2010

From Yayoi Kusama’s pioneering works of abstract expressionism to Takashi Murakami’s works that express Japanese Pop Art, the exhibition Trans-Cool TOKYO provided an opportunity to view works by groundbreaking Japanese artists who have made an indelible impact on contemporary art. Featuring over 40 works from the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo collection, this exhibition also told the story of how Japanese artists, since the second half of the 1990s, have established their own creative identities within the context of global pop culture. Working across all mediums, from painting and sculpture, to performance, photography and video, the featured artists have created works in response to the onset of the information age and the greater freedom and uncertainties in contemporary society. Trans-Cool TOKYO was co-organised by the Singapore Art Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo. It ran from 19 November 2010 to 13 February 2011.

The Formative 60s and 70s

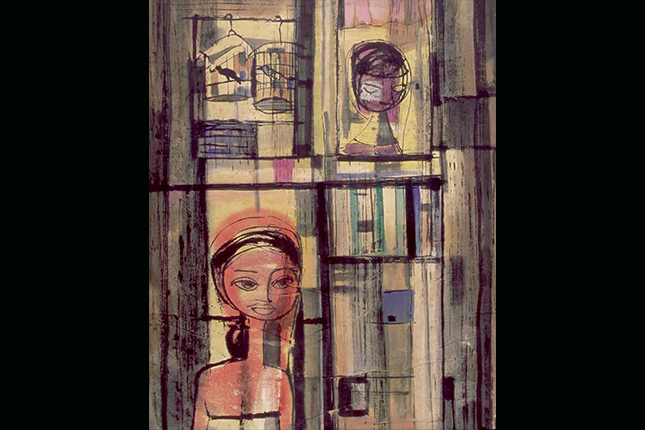

After Japan’s defeat in the Second World War, many Japanese artists born or practising their art in the 1950s sought to redefine their identity with reference to Western culture. This is typified by the work of Yasumasa Morimura (b. 1951) in this exhibition. Here, Morimura depicts himself in well-known Western paintings, such as in Criticism and the Lover A, B, C where his face is inserted into each of the apples and oranges of the famous still-life paintings by French impressionist Paul Cézanne.

Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo Collection.

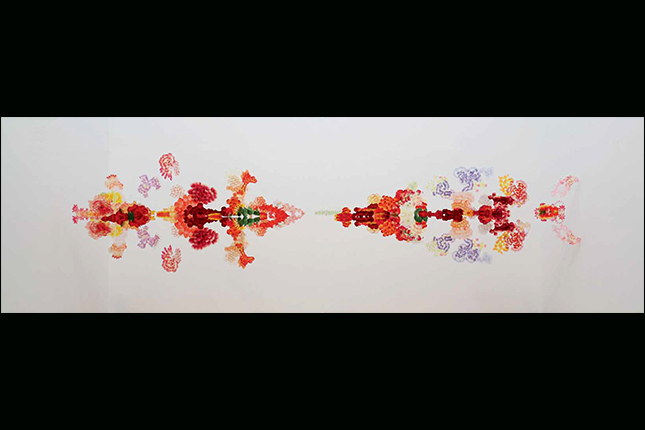

Suffering from psychoneurosis and schizophrenia since early childhood, Yayoi Kusama (b. 1929) experienced hallucinations in which everything she saw was covered with polka dots and negative forms. Transforming otherwise common objects and scenes into seemingly repetitive but unique organic shapes, Kusama’s work is a manifestation of intense focus and obsession. Her work Walking on the Sea of Death (1981) comes from a mental image she had of a boat covered with silver rhizoids (phalluses) printed repeatedly all over the inside of a room.

Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo Collection.

The Postmodern 80s

Artists who started their practice in the 1980s had less of an inferiority complex towards, or an over-awareness of the West. This was also a time of economic boom in Japan, where the strong Japanese Yen made it easy for these artists to travel abroad. These artists adopted a more international perspective and tried to develop a visual language that would enable them to stand on par with Western artists.

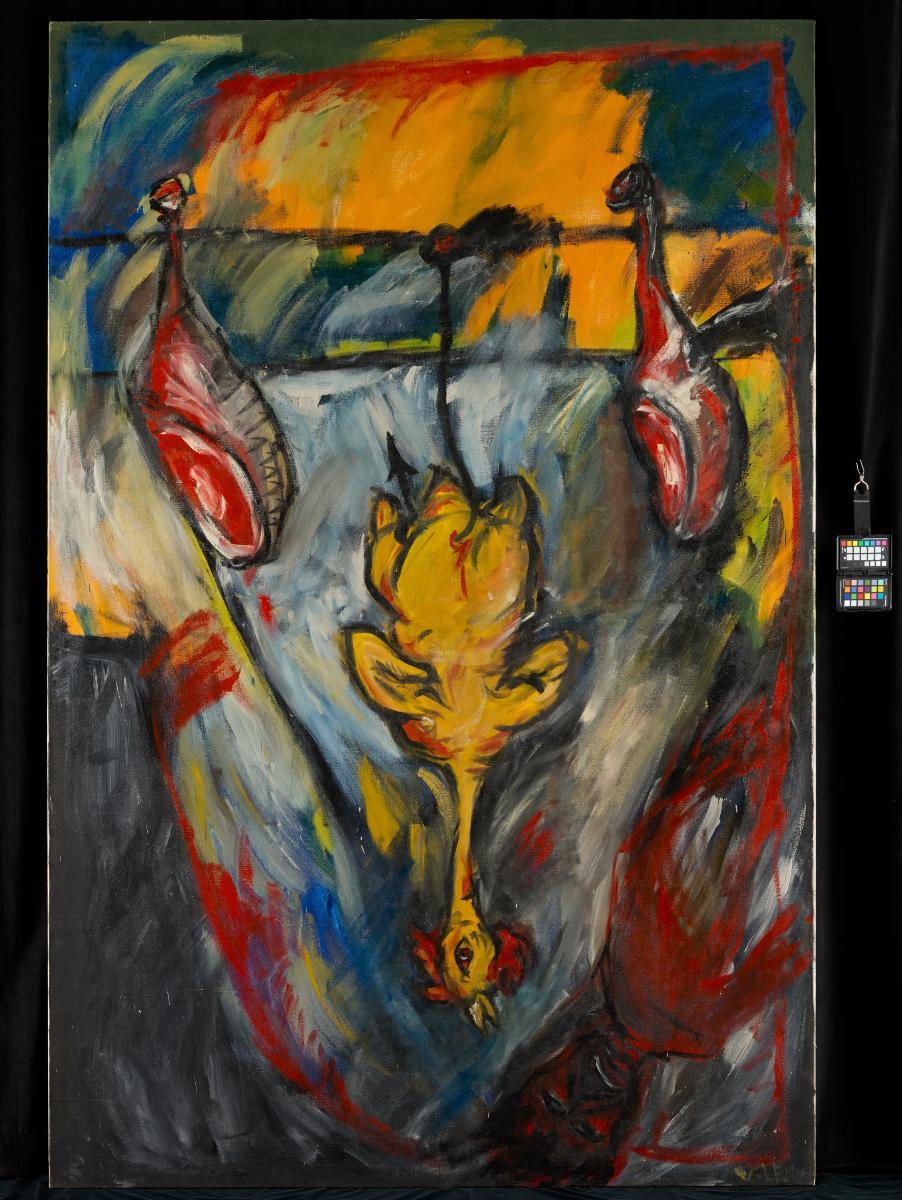

The works of Yoshitomo Nara (b. 1959) and Takashi Murakami’s (b. 1962) have come to be part of Japanese pop art and exhibit the Japanese quality known as kawaii (suggesting cuteness). The adult world and its sensibilities were rejected for immaturity and innocence. Nara’s manga-esque children in his paintings react to the state of the world with suspicion and anger, glaring at the viewer. Murakami’s works of animal anime icons that divide and proliferate at a cellular level appear as cute yet at the same time creepy protean monsters.

Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo Collection.

The late 1980s and early 1990s saw the end of the economic bubble, resulting in a “lost decade” of low economic growth. This insecurity over the future translated to Japanese artists taking inner, personal exploration even further, continuing ways to connect with personal communities otherwise overlooked by governments and conventional organisations. Artists such as Kohei Nawa (b. 1971) and Haruka Kojin (b. 1983) belong to this generation of artists.

Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo Collection.

Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo Collection.

New Japanese Art

One of the foremost characteristics of Japanese contemporary art of today is a growing interest from its artists in their own culture rather than that of overseas culture. Perhaps due to the declining Japanese economy, falling birth rates and ageing population, there is increased conservatism, conformism and introspective tendencies among Japanese youth today. Art is no longer viewed as something equated with privilege and prestige; instead it is increasingly tied closely to everyday life, and art overlaps with other fields more now, such as fashion, design, video, film and technology.

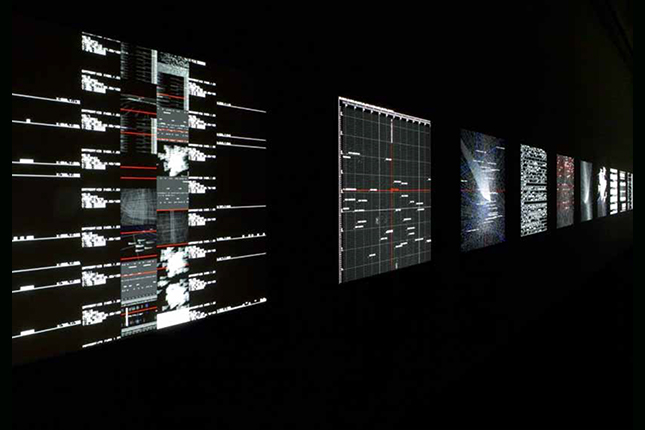

Ryoji Ikeda (b. 1966) composes his works based on reducing from our environment the behaviour of sound and light waves into the very basic elements known to man such as pixels and sine waves (a mathematical construct that deciphers and decodes sound into its different wavelengths). Wanting to make visible the invisible, Ikeda reduces the daily stimuli we encounter in our everyday lives and then puts them back together digitally, re-composing our environments into art installations with light and music that re-interact with our physical bodies on a digital plane.

Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo Collection.

Recycling a telephone booth into a one-man disco, Kiichiro Adachi’s (b. 1979) work e.e.no.24 sheds light on the relationship between people in society by introducing elements of the fantastic and the magical. The work allows the shy dancer, too self-conscious to dance in front of others, to do so in its magical mirrored interior so that he or she is only able to see himself or herself. The booth, whose walls are one-way mirrors, however, also reveals the dancing figure within to those standing on the outside.

Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo Collection.

What will be the future direction of Japanese contemporary art? If the works shown in this exhibition provide any clue, aesthetics and sensibilities still rooted in local culture, yet informed by globalism, will inspire new Japanese contemporary art. This art will remain deeply connected to the individual in society, and will be part of the ongoing search to understand the relationship between oneself and the world.