Singapore’s Very Own Henry Ford

Tan Kah Kee left his home town in Fujian, China for Singapore at the age of 16, having received a Confucian-centric education.

At work, Tan was diligent, rising through the ranks of Chop Soon Ann, his father’s rice mill and

sundries business in Singapore.3 By the 1900s, his father’s business ventures began to falter4 as a result of

misappropriation and mismanagement. Tan worked to shut the companies down and was singularly focused on clearing their debts.

Tan later built his own empire.

From a single pineapple canning factory, Tan soon had three such enterprises under his name.5

With these successes, he was able to buy back the original home of Chop Soon Ann in North Boat Quay.6

There, he established the Khiam Aik rice mill.7 When his businesses faced setbacks, he branched out into new markets

and other sectors, staying nimble and conscious of global trends. At one point, his empire comprised pineapple and

rubber plantations, rice mills and a biscuit factory. Tan also got involved in the shipping industry as well as the

manufacture of tyres and shoes.8

Tan later built his own empire.

From a single pineapple canning factory, Tan soon had three such enterprises under his name.5

With these successes, he was able to buy back the original home of Chop Soon Ann in North Boat Quay.6

There, he established the Khiam Aik rice mill.7 When his businesses faced setbacks, he branched out into new markets

and other sectors, staying nimble and conscious of global trends. At one point, his empire comprised pineapple and

rubber plantations, rice mills and a biscuit factory. Tan also got involved in the shipping industry as well as the

manufacture of tyres and shoes.8

In the mid-1920s, Tan’s empire created jobs for more than

30,000 people in Singapore and beyond. His success was attributed to his fastidious nature and

involvement in all stages of the supply chain — much like Henry Ford, the great industrialist.9

Tan took several employees under his wing, his mentorship and tutelage leading to the rise of

other movers and shakers such as Lee Kong Chian and Tan Lark Sye.10

Tan’s businesses wound up “naturally”, having been

impacted by international financial cycles and catastrophes such as the Great Depression.11

Historian Wang Gungwu, who described Tan as “one of the earliest global Chinese entrepreneurs

that the Nanyang produced”, said it was precisely because of the global reach of his businesses

that Tan was subjected to such crashes.12

Instead of resting on his laurels,

Tan reinvented himself to serve his communities in Singapore and China.

Tan Kah Kee. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

Tan Kah Kee. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

Confucian consciousness

A firm believer in education as a social leveller,

and continually guided by Confucian values, Tan was involved in setting up more than 10

schools and institutes such as Tao Nan School, Ai Tong School, and The Chinese High School (now Haw Chong Institution after a merger with Hwa Chong Junior College)13 in Singapore.

In China, he pushed for the establishment of Xiamen University.14

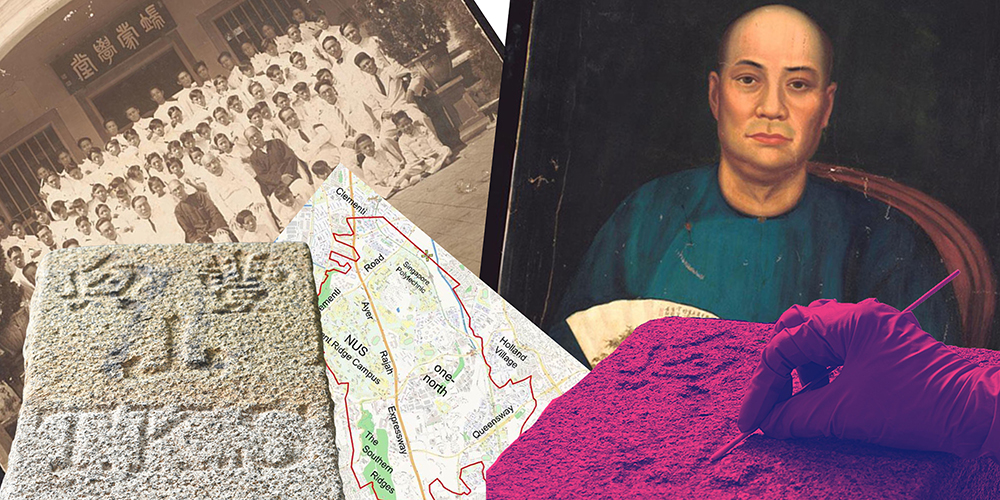

Jimei Secondary School which was established by

Tan Kah Kee in his hometown in Fujian, China. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

Jimei Secondary School which was established by

Tan Kah Kee in his hometown in Fujian, China. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

Tan Kah Kee giving a thank you speech at the Ee Hoe Hean

Club in Bukit Pasoh in the 1940s. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

Tan Kah Kee giving a thank you speech at the Ee Hoe Hean

Club in Bukit Pasoh in the 1940s. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

In 1923, Tan started Nanyang Siang Pau, a Chinese

newspaper to encourage a reading culture and promote businesses.

15

In 1929, he was elected to serve as

president of the Hokkien Huay Kuan.16

He used its platform to call for unity among Singapore’s varied Chinese

dialect communities and to put an end to social ills such as opium addiction.

His mind was also on his home country. To this end, he set up a number of

funds to provide relief for flooding victims, and to render aid following the outbreak of war between China and

Japan in 1937. The following year, he served as head of the

South-East Asia Federation of the China Relief Fund to further support the anti-war effort.

When the Japanese reached Singapore in 1942,

Tan rallied members of the Chinese community to aid the British in repelling

the invaders.17 For all his anti-war efforts, Tan was a prime target of the

Japanese and thus had little choice but to leave Singapore. He ended up in

Marang, Indonesia where he spent his time writing.18

Tan Kah Kee writing a letter. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

Tan Kah Kee writing a letter. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

After the war, Tan returned to

Singapore and launched the Nan Chiao Jit Poh, a newspaper which took on

an unfavourable tone towards the ruling Kuomintang in China.

The British, fearing that the growing politicisation of Chinese

in Malaya and Singapore, grew increasingly apprehensive about

individuals such as Tan.19 At one point, they even considered

cancelling his British citizenship.20 Tan left Singapore for

China in 1950, and in 1957, renounced his British citizenship.

In China, he dedicated his resources towards rebuilding and reconstruction efforts.

When he died in Beijing, China at 87,

Tan was given a state funeral by the Chinese

government to honour his contributions.

His final resting place is in Ao Yuan, Jimei, China.

In Singapore he’s remembered in various ways.

For instance, a train station which opened in Bukit Timah in 2015 bears his name.

Tan Kah Kee holed himself up in this house in Marang, Indonesia during World War II. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

Tan Kah Kee holed himself up in this house in Marang, Indonesia during World War II. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

Tan Kah Kee's tombstone. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

Tan Kah Kee's tombstone. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)