Text by: Stefanie Tham | Manager, Education & Community Outreach & Raudha Muntadar | Senior Officer, Education & Community Outreach

MuseSG Volume 10 Issue 2 - 2017

Encountering the sheer number of people at Tampines today can sometimes leave one overwhelmed. From its multiple shopping malls and offices to Our Tampines Hub, the estate’s newest community and lifestyle destination, Tampines is often crowded with throngs of people going about their daily routines. According to a 2016 survey by the Department of Statistics, Singapore, Tampines was home to around 250,000 residents and was the third most populous residential town in Singapore after Bedok and Jurong West at the time. It is evident from the loads of passengers constantly spilling out from Tampines Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) Station that Tampines is a town bustling with activity.

Yet, long-time residents who have lived in Tampines since the town was built in the 1980s recall a different picture of the area. Anwar Bin Haji Mawardee, who first moved into Tampines in 1985, remembers it as a desolate and empty new town: “At that time there weren’t as many flats [as there are today]. It wasn’t as crowded as it is now... When we met our friends from other parts of the island, they would say, ‘Wah you live in Tampines, you ulu type ah.’”

Clarice Teoh, another resident who moved into the town in the early 1980s, echoes similar sentiments: “When we selected a at here, we were a bit hesitant. It was a bit like an ‘end of the earth’ feeling. Bedok was popular, and it was already built up, and most people didn’t think beyond Bedok in the east.”

Before the MRT line extended into Tampines, residents had to alight at Tanah Merah to take a feeder bus. There was also no proper bus interchange, save for a makeshift interchange along Tampines Avenue 5.

Tampines resident, Wendy Oh, recalls that the streets were barely lit at night: “When we moved here during the early 1980s, it was very remote and really dark at night. You wouldn’t dare to go out at night as there were no street lights, and many of the HDB blocks were still under construction. I recalled asking myself then, why did I move to such an ulu area with no amenities?”

Courtesy of Housing & Development Board.

These experiences of living in Tampines Town in its nascent years seem to mirror that of village life in the district before the 1980s. Ulu, which means “remote” in Malay, was a term often used to de ne Tampines even before the residential town was built. Due to the fact that until the 1970s, old Tampines Road was the only thoroughfare that traversed across north-eastern Singapore towards Changi, the district was relatively isolated from other parts of the island.

Courtesy of Tampines GRC Community Sports Clubs.

Tampines Road began in 1847 as a bridle path accommodating horses and pedestrians. The road spanned from the 6th milestone of Serangoon Road to Changi Road near the eastern tip of Singapore. Many early kampong (village) dwellers settled along this road, and some of the villages here included Kampong Teban, Teck Hock Village, Hun Yeang Village and Kampong Tampines.

Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Travelling into and out of the district was often a challenge for the villagers living in Tampines. Back then, bus services from town terminated at the 6th milestone of Serangoon Road (known as Kovan today), and commuters had to continue their journey into Tampines on pirate taxis and privately-owned buses.

F W York Collection. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Yvonne Siow, a former teacher at Tampines Primary School in the 1960s, recalls: “[The drivers] would wait to get as many people into their taxis as possible and not all the pirate taxis would... travel deep into the kampong, as they would have trouble finding a customer on the way back. So some people resorted to hitching a ride from cars or lorries going in.”

The area was so withdrawn that even in the late 1970s, when other parts of Singapore were being modernised, smaller streets located further down from Tampines Road remained unknown and difficult to locate. Jimmy Ong, who formerly lived in a Tampines kampong, shares: “We could give visitors our address, but there was no way to tell them exactly where we stayed. What usually happened was that we would go out to the [nearby] school to wait for them and bring them in.”

From the 1960s to the 1980s, Tampines was also associated with the sand quarrying and waste disposal industry, which not only damaged the surrounding environment, but also made living there an unpleasant experience. Sand from Tampines was used for the building of Housing & Development Board (HDB) towns in the 1960s, and demand for the material was so high that at its peak, there were 26 sand quarries operating in Tampines.

Courtesy of Housing & Development Board.

Courtesy of Tampines GRC Community Sports Clubs.

Quarrying left gaping holes in the ground, and runoff from the quarries often resulted in floods and choked drains. In addition, the nearby Lorong Halus landfill, sometimes referred to as the “Tampines dumping ground”, emitted foul stenches that could reach as far as MacPherson on the occasions when its garbage mounds – as tall as 10 storeys – caught fire.

Courtesy of National Environment Agency.

Nevertheless, despite these inconveniences, former kampong dwellers also fondly reminisce about the close-knit relationships fostered with their neighbours and friends, as well as the community-centric spirit that was part of daily life.

Florence Neo, who grew up near Hun Yeang Village, elaborates: “To me, kampong spirit means that whenever there is a need, everybody chips in to help. When my mum gave birth to me and my siblings, her neighbours came over and taught her what to cook and advised her what to eat.”

Villagers also bonded over simple entertainment such as catching insects or watching wayang (“street opera” in Malay) shows that were organised by the Chinese temples in the vicinity. Albert Peh, who lived in Kampong Teban, remembers the large crowds of villagers who would gather at the Tua Pek Kong temple during a wayang show. He shares: “For us kids, we were most excited by the pushcarts that came with food, sweets and flavoured ice balls. There were also tikam tikam (“games of chance” in Malay) stalls, some with roulette wheels, [where] you could win toys or money.”

Courtesy of Tampines GRC Community Sports Clubs.

Courtesy of Albert Peh.

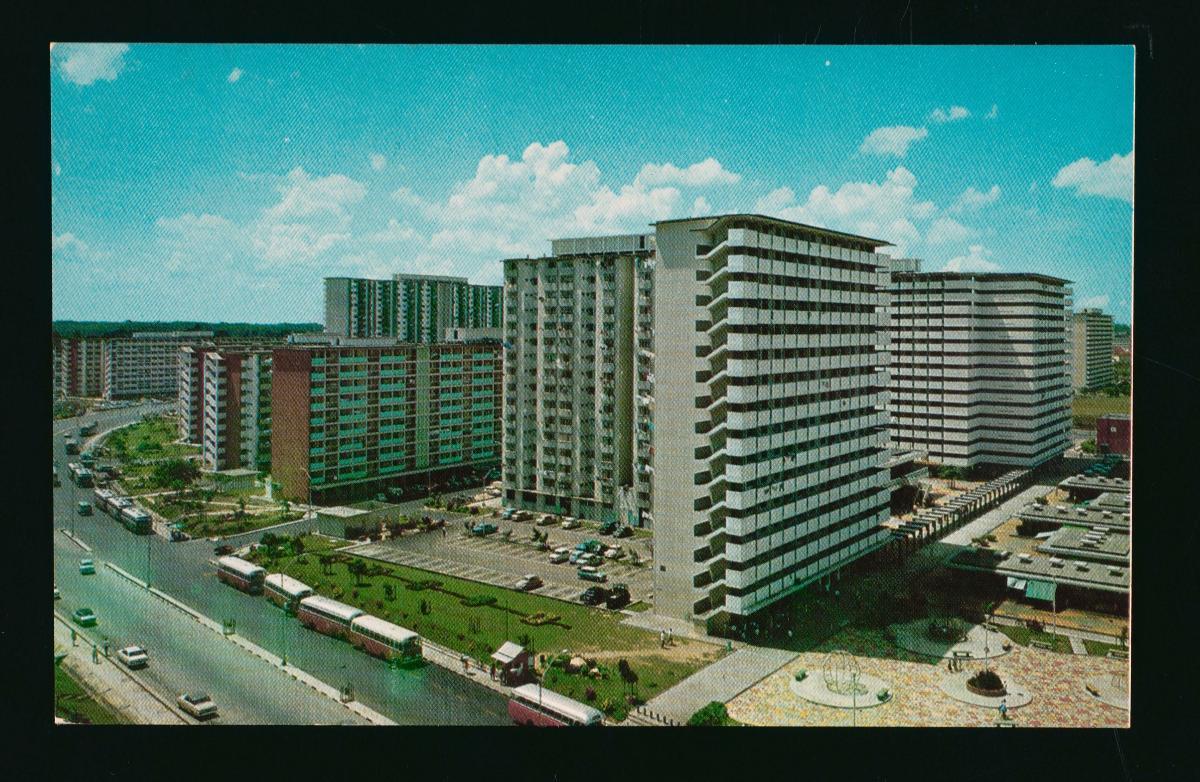

These images described by former kampong villagers and early residents of Tampines Town are a stark contrast to the modern and bustling residential town we see today. It was highly unlikely that anyone living here in the 1980s could imagine that Tampines would receive the World Habitat Award from the Building and Social Housing Foundation and UN-Habitat just a decade later in 1991, even beating out contending entries from Vancouver, Canada and Boston, USA. Overnight, Tampines Town became recognised as an exemplar of “high-quality, high-density and affordable housing”, and was touted as a model that cities around the world could replicate.

Courtesy of Housing & Development Board.

The award was a historic moment for Singapore as the achievements of the country’s public housing were finally being recognised on an international level. By the time HDB started designing Tampines Town in the 1970s, Singapore’s post-war housing shortage had been largely resolved, allowing the Board to channel its resources into improving its town planning models.

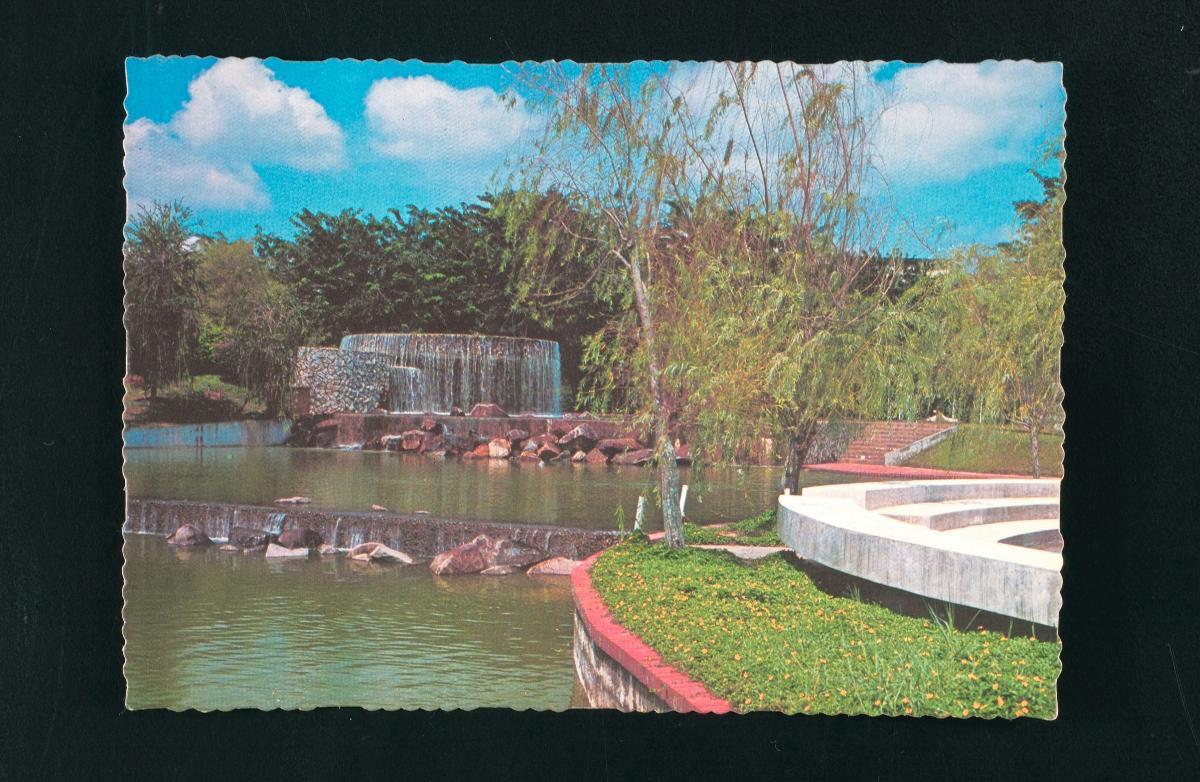

The award was an affirmation of the many town planning innovations that the HDB pioneered in Tampines, which sought to foster community bonds and encourage neighbourly interaction. The innovations included the introduction of integrated green corridors – a precursor to today’s ubiquitous park connectors, as well as the precinct concept, which brought amenities closer to residents and encouraged greater social interaction between residents from different socio-economic backgrounds.

The HDB also sought to capture the unique identity and heritage of Tampines in its architecture. HDB architect Lee-Loy Kwee Wah wanted to reflect the fruit farms of rural Tampines in her designs of the town’s public playgrounds. After briefly experimenting with different fruit designs (including a durian playground that was later deemed too risky due to the fruit’s spikes), she produced three playgrounds that were installed in Tampines: the watermelon, mangosteen and pineapple playgrounds. The former two playgrounds can still be found in Tampines Central Park, and have become iconic symbols of Tampines.

Other town planning innovations included blocks of varied designs and heights, open spaces for communal activities, and a well-integrated transport network system consisting of the MRT and Pan- Island Expressway.

In 1991, the town entered yet another phase of its development when it was designated Singapore’s first Regional Centre, a concept spearheaded by the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) to grow commercial centres in suburban areas. Major corporations soon established themselves in Tampines, including the former Pavilion Cineplex and DBS Tampines Centre, which housed Japanese retailer Sogo.

Courtesy of Urban Redevelopment Authority.

The concept also paved the way for the construction of large shopping malls in Tampines, starting with Century Square in 1995 and Tampines Mall the following year.

Courtesy of Urban Redevelopment Authority.

For the generation that grew up in Tampines in the 1990s, these malls were the setting for many outings with friends and families.

Former Tampines resident Bryne Leong shares: “[I remember going to] Pavilion and watching Disney movies and Titanic. There was a Burger King downstairs where a schoolmate and I would share a meal and fight over French fries.”

Although Pavilion and Tampines Centre have since been demolished, Tampines Mall, Century Square and the town’s latest shopping mall, Tampines One, have taken over as popular hangouts for Tampines residents.

As the town gradually matured, stories of ulu kampongs and a dark, desolate town also began to fade into history. Nevertheless, aspects of Tampines’ heritage can still be found at some sites today, especially in its religious institutions.

For example, hidden inside the grand Tampines Chinese Temple at Tampines Street 21 is a temple plaque that dates to 1851. The plaque belongs to the Soon Hin Ancient Temple, a Taoist village temple that was first set up in an attap hut at Jalan Ang Siang Kong at the 11th milestone of Tampines Road. Similarly, Masjid Darul Ghufran at Tampines Avenue 5, had its origins in the multiple surau (“prayer houses” in Malay) which served Muslim villagers in the east. These surau raised funds for the building of the mosque, which was completed in 1990.

Courtesy of Masjid Darul Ghufran.

Finally, while almost all of Tampines’ former quarries have been filled in, two quarry pits still remain – one has been converted into Bedok Reservoir, while another lies abandoned and hidden behind a row of trees along Tampines Avenue 10.

TAMPINES HERITAGE TRAIL

Many of the heritage sites in Tampines can be explored through the Tampines Heritage Trail that was launched in September 2017. It chronicles the history of Tampines from the 19th century to the present day, piecing a layered narrative of the town through archival records, social memories, photographs and maps.

Trail goers can embark on any of the three specially curated thematic short trails that explore different aspects of Tampines’ heritage. The Tampines Town Trail explores some of the town planning innovations and sites of everyday heritage in the town; the Religious Institutions Trail explores the diverse houses of faith found in the area and highlights its unique architecture and practices; and the Green Spaces Trail is NHB’s first cycling trail, taking cyclists to heritage and scenic locales in Tampines, including former kampong locations, and a former landfill turned wetland.

The launch of Tampines Heritage Trail follows the August 2017 opening of Our Tampines Gallery, a gallery that showcases the heritage of Tampines with a focus on community-contributed stories and collections. Our Tampines Gallery is located within the Tampines Regional Library at Our Tampines Hub, the first integrated community and lifestyle hub in Singapore. Presented by NHB, the gallery is developed together with the community, and aims to make heritage more accessible and inclusive for everyone. Its inaugural exhibition is titled Tampines: A History, and presents an overview of the history of Tampines through maps, photographs and objects.

Download the trail booklet and map at NHB’s portal here.

Our Tampines Gallery, a community gallery that showcased the rich heritage of Tampines Town, ceased operations on 31 October 2023