Text by Kan Shu Yi

BeMuse Volume 5 Issue 2 – Apr to Jun 2012

A dive for sea cucumbers. A mound sighted. An accidental and amazing discovery was made.

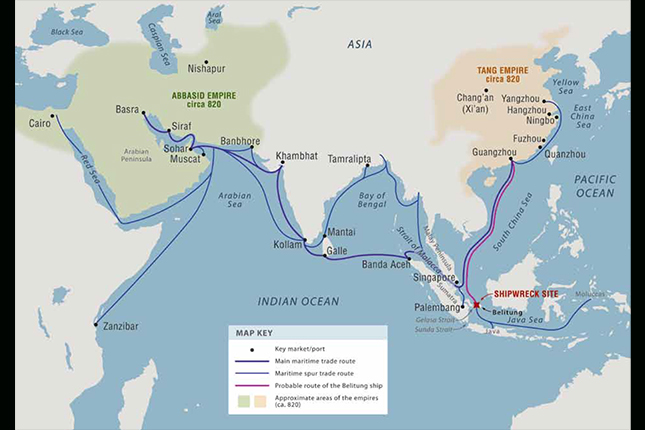

Lying silent for more than a millennium underwater, a chance discovery by local fishermen in 1998 brought the Belitung cargo to light. The wreck was found in relatively shallow waters at a site approximately 17 metres deep and a few kilometres off the shores of Belitung Island in the Java Sea. Tragedy probably struck when the ship crashed into reefs in the area, referred to as Batu Hitam (‘black rock’).

Authorised by the Indonesia government, salvagers proceeded to recover some 60,000 objects from the wreck site over two seasons of excavation work. The bulk of the finds were Chinese ceramics from the Tang period (618 – 907), comprising both mass produced and rare examples. Bullion in the form of silver and lead ingots was also found. The most astonishing finds were perhaps the exquisite pieces of Chinese metalwork – gold, silver, and bronze – which suggested that the people on board had a connection with the highest strata of Tang society.

Photograph by John Tsantes & Robb Harrell, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

The extraordinary nature of this find was heightened by the vessel itself. Examination of the ship’s construction methods and analysis of its timbers revealed that the ship was most likely to be of Arab origin. The ship’s hull were formed by planks sewn together using vegetal fibres instead of iron fastenings, the latter a feature of Chinese ships. The timbers, consisting of African hardwoods, were common materials used by shipbuilders from the Gulf region. Thus, this shipwreck stands as the earliest Arab vessel to have been discovered in Southeast Asian waters, a testament to the bustling maritime trade and sprawling commercial networks during the ninth century.

Yet, much remains a mystery. Just as the ship’s exact place of origin is undetermined, so is its final point of departure. It was probably Yangzhou (in Jiangsu province) or Guangzhou (in Guangdong province), both bustling trade hubs in ninth-century China, from which the Belitung ship sailed. And where was the ship heading when it ran into reefs off Belitung Island? It appears to have deviated from the main shipping route that most vessels took when traversing the region. Was it perhaps blown off course? Or had it taken another course to avoid pirates? More likely, it was dropping off ceramics or acquiring new trade products and provisions at a port in Java.

Humble utilitarian items, which shed light on the lives of those on board, added another layer of interest to this discovery. The crew and other passengers on the vessel were most likely multinational. Arab or Persian traders probably chartered the ship, and brought with them vessels such as the turquoise-glazed amphora. On the long voyage, it would have made multiple stops in India and Southeast Asia to recruit new crew. There were most probably Chinese merchants on board also, as suggested by the inkstone used for writing.

Photograph copyright Singapore Tourism Board.

The exact date when the ship embarked on its final journey has also been much discussed. The ceramics found in the shipwreck are the types produced in the ninth century, a dating which matches the results of radiocarbon tests on organic materials from the wreck. A date equivalent to 826 is thought to be incised on one of the Changsha bowls. It is thus likely that the Belitung ship sailed in the second quarter of the ninth century, possibly within a few seasons of the bowl’s manufacture.

Photograph copyright Singapore Tourism Board.

The Cargo

A commodity difficult for camels to transport via the overland Silk Road, shipping had made possible the large-scale export of ceramics from the mid-Tang dynasty. The Belitung ship carried close to 60,000 pieces of Chinese ceramics. But breakages were found at a relatively low level of approximately 20 percent, which suggests that there were more than 70,000 pieces of ceramics in the ship’s original cargo. This is an impressive figure considering that the vessel measured approximately 18 metres by 6.5 metres. It carried numerous storage jars, of which many with larger openings were packed with ceramic bowls. The manner of packing – many bowls were tightly arranged in a “helixical” manner and probably cushioned by straw – enabled the boat to carry such an enormous load. This packing method and the silt of the seabed also protected most of the cargo from damage.

The size of the cargo underscores the great popularity of Chinese ceramics, which were valued for their beauty, strength, and durability. These qualities were unrivalled by ceramics from other parts of the world. To cater to the growing demand, new kilns sprang up in many provinces in China, while old ones changed their technologies and products. For instance, there was a shift from producing low-fired tomb pottery to high-fired tableware. Assembled from diverse sources, the repertoire of wares in the cargo highlights the vitality and competitiveness of the Chinese ceramics industry. It also shows the merchants’ entrepreneurial ways as they targeted different groups of clientele by exporting a range of goods.

Changsa Wares

Ceramics from the Changsha kilns in Hunan province dominated the cargo of the Belitung wreck. Approximately 57,500 items were produced by Changsha potters and among these were some 55,000 bowls. Most of these bowls carry one of a few basic patterns, which include foliage, flowers, birds, and clouds. However, these were created by many different artisans, hence giving an impression of a huge variety of designs that ranged from the realistic to the abstract. This staggering quantity of ceramics reflects the organisational and productive capacities of China’s ceramic industry. Relatively isolated from the Tang court, major commercial centres and other kilns, Changsha potters developed a distinctive decorative style, featuring lively designs painted with iron and copper pigments. They introduced underglaze painting, blazing the way for the development of this form of ornamentation in Chinese ceramics.

The Changsha potters made a wide variety of forms and many of these were represented in the Belitung cargo. Apart from daily utensils like bowls and ewers, they also fashioned toys and scholars’ implements such as water droppers. The potters often instilled an element of fun into their wares. A fine example is the incense burner that has a cover topped with a man tussling with a lion. The man is forcing open the mouth of the beast, which creates the hole where the smoke escapes.

Photograph copyright Asian Civilisations Museum.

Changsha wares appear to have been popular in both domestic and overseas markets. Significant quantities have been excavated at the port of Yangzhou, where they must have been stored before being shipped. They have also been found in large amounts in Southeast Asia, particularly in Indonesia.

Other Ceramics

In addition to Changsha wares for the wider market, the ship ferried a selection of finer ceramics, reflecting the prevailing taste in China. Such an assortment of goods was made possible by the network of waterways (rivers and the Grand Canal) which linked northern and southern China, as well as inland cities to coastal ports. The items included high-fired white wares that represent the ceramic achievements of northern China, and green-glazed stone wares which were premier products of the south during the Tang period. During the eighth and ninth centuries, Yue celadons from Zhejiang and Hebei’s Xing white wares were regarded as symbols of beauty, elegance, and wealth. The Chinese affection for monochrome ceramics crystallised at this time and reached its height in the Song dynasty (960 – 1279).

The Tang cargo also contained three extremely rare blue-and-white dishes, which are among the earliest complete Chinese blue-and-white ceramics known.

Unlike the ceramics mentioned in the previous paragraphs, the production of blue-and-white wares was short-lived during the Tang dynasty, probably because it did not match the prevailing Chinese taste. The lozenge with leafy fronds, seen on the Belitung blue-and-white dishes, is a motif that originated in eighth- or early ninth-century Iraq. The cobalt used to paint the designs may have come from the Abbasid Empire. They were made chiefly for export, and the Belitung examples may have been experimental prototypes sent for the approval of Abbasid clients.

White Wares

Probably the most valuable ceramics on the ship was a relatively small consignment of white wares. Comprising some 300 pieces, they were drawn from three or four different kilns in northern China. The finest were produced at the Xing kilns in Hebei province. Thinly potted and covered with a glossy clear glaze, they were likened to snow and silver. The exquisite Xing wares were imitated by the Ding kilns located farther north in Hebei and the Gongxian kilns in Henan province. Although connoisseurs of Tang ceramics ranked Xing wares as supreme, the products of the Xing and Ding kilns were often very similar and almost indistinguishable. Attribution was made more difficult by the poor condition of some of the finds.

Green-splashed Wares

Almost 200 pieces of white wares decorated with copper-green splashes were recovered from the wreck. Chemical analysis of retrieved shards suggests that the majority of these ceramics came from the kilns at Gongxian in Henan province. Gongxian potters probably sought to develop alternative product lines as their white wares faced serious competition from Xing ceramics. These more colourful products appealed in particular to foreign markets. Tang green-splashed wares have been found at the Abbasid city of Samarra (Iraq) and the port of Siraf (Iran), among many other sites in the Near East region.

Green Wares

The most esteemed green wares from the Yue kilns in Zhejiang province were likened to jade. Lu Yu, a tea connoisseur from the Tang dynasty, rated Yue tea bowls most highly in his Chajing (The Classic of Tea), the first monograph on tea in the world. The lustrous glaze of Yue wares was perceived to enhance the tea’s colour. Yue ceramics were thus often undecorated, emphasising the beauty of their glaze and form instead.

Of the approximately 900 pieces of green wares found on the ship, only around 200 were from the Yue kilns. The rest were products of Guangdong, which consisted mainly of sturdy storage containers and a small selection of tableware. The figures reflect the limited output of the Yue kilns, which seem to have rather strict quality control. Just like the many ceramic wares found on board, there was an enthusiastic foreign market for green wares, as indicated by their discovery at sites as far afield as Samarra in Iraq, Siraf in Iran, and Fustat (old Cairo) in Egypt.

Precious Metals

The gold, silver, and bronze objects found in the shipwreck constituted one of the most important discoveries of Tang metalwork, and the first outside of China. Especially rare are the objects of pure gold: an octagonal cup, three shallow bowls, and three dishes. Also discovered were silver boxes of varying forms, possibly used as containers for cosmetics, incense or medicine; and a richly decorated wine flask.

A total of 29 Chinese bronze mirrors were found in the wreck – one of the largest assemblages of Tang mirrors ever discovered. Such a large collection suggests that the mirrors were meant to be sold, and not the crew’s personal possessions. Among the mirrors was the only surviving example of a celebrated form called “Jiangxin” or “Yangxin” (Heart of the Yangzi River), which was previously recorded in texts. It was supposedly cast on board a boat moored in the Yangzi River at Yangzhou and charged with cosmological powers. Of extremely high quality, it was also presented as tribute to the imperial court.

Many of these objects were probably made in Yangzhou, a leading centre of fine craft. It remains a mystery for whom these luxuries were intended. The gold objects might have been gifts from the Tang emperor in return for tribute presented by a foreign mission. Or they might have been used by Chinese officials to ease trade negotiations over desirable imports from abroad, such as spices, pearls and other exotic rarities. Whichever the case, these extravagant articles indicate that the masters of the Belitung ship were engaged in dealings with the elite of Tang society.

Although there are still many puzzles surrounding the ship and its excavation has raised debate, the importance of this Tang shipwreck is immense. Its extensive cargo is one of the most significant assemblages of Tang artefacts found at a single site. Not only does it serve as a time capsule of ninth-century Tang China, it has also revealed the interactions between China, Southeast Asia and the Middle East, showing an already very well connected world.

Kan Shuyi is Curator (China), Asian Civilisations Museum.

EXHIBITION INFORMATION:

Tang Shipwreck Gallery

As of 2018, this exhibition is permanent.

Asian Civilisations Museum, Empress Place

This exhibition is organised by the Asian Civilisations Museum and the Singapore Tourism Board. Unless otherwise stated, the objects on display are from the Tang Shipwreck Treasures: Singapore’s Maritime Collection. The acquisition was made possible by the generous donation of the Estate of Tan Sri Khoo Teck Puat. The recovery and conservation of the collection was undertaken by Tilman Walterfang.