By Heidi Tan, Senior Curator, Southeast Asia Asian Civilisations Museum

Images: Asian Civilisations Museum

BeMuse Volume 3 Issue 3 – Jul to Sep 2010

A Centre for Cultural Exchanges

A Centre for Cultural Exchanges

Sumatra’s position along the Straits of Malacca has resulted in a cultural legacy that illustrates how various streams of influence took place. Over the past two millennia, Indian, Chinese, Islamic, regional and European influences prevailed at different times.

The material cultures presented in the exhibition Sumatra: Isle of Gold included Bronze-Age objects of the early Austronesian communities, Hindu-Buddhist materials of the maritime kingdom of Srivijaya (7th-13th centuries), Chinese materials both imported and locally made, court arts of the coastal Islamic sultanates such as Aceh, Jambi and Palembang, Riau-Lingga and Siak. Artefacts that show interactions with remote cultures such as Batak and Nias and objects made in response to European influence during the colonial period, one also included.

Indian Influences – The Legacy of Ancient Hindu-Buddhist Kingdoms

Indian sources from the 3rd century BCE and later mention of Suvarnadvipa or ‘Gold Island’, which probably included the region and later Sumatra. Although gold was mined in Sumatra, natural resources such as benzoin (a fragrant resin used in perfumery and ritual offerings), camphor (another aromatic resin obtained from a forest tree) and by the 15th century, pepper, were highly sought after by overseas markets. These goods were traded for prized imported commodities such as Indian printed cloth and Chinese ceramics.

Collection of the National Museum of Indonesia.

Hindu-Buddhist traditions probably arrived from India during the early centuries of the Common Era. The writings of the Chinese monk and pilgrim Yi Jing, provide some of the earliest evidence of the Srivijaya kingdom and Buddhist centre at Palembang during the late 7th century. Additional evidence for this kingdom arises from several inscriptions in the Indian Pallava script such as the Kota Kapur stele (dated 686 CE) from Bangka Island off the east coast of Sumatra. The stele’s location indicates an extensive network rather than a state with defined borders. It also provides evidence for the use of Indic scripts as the foundations of Old Malay and other local written languages.

Collection of National Museum of Indonesia.

Palembang’s authority declined following Javanese attacks during the late 10th and 13th centuries, and the invasion of Indian Chola armies in the early 11th century. Eventually, the Malayu kingdom took control, but was forced to give way to the East Javanese kingdoms of Singhasari and then Majapahit during the 14th century. Malayu eventually withdrew inland to the Padang highlands, leaving behind an artistic legacy that reflects strong Javanese influences and the practice of Tantric Buddhism.

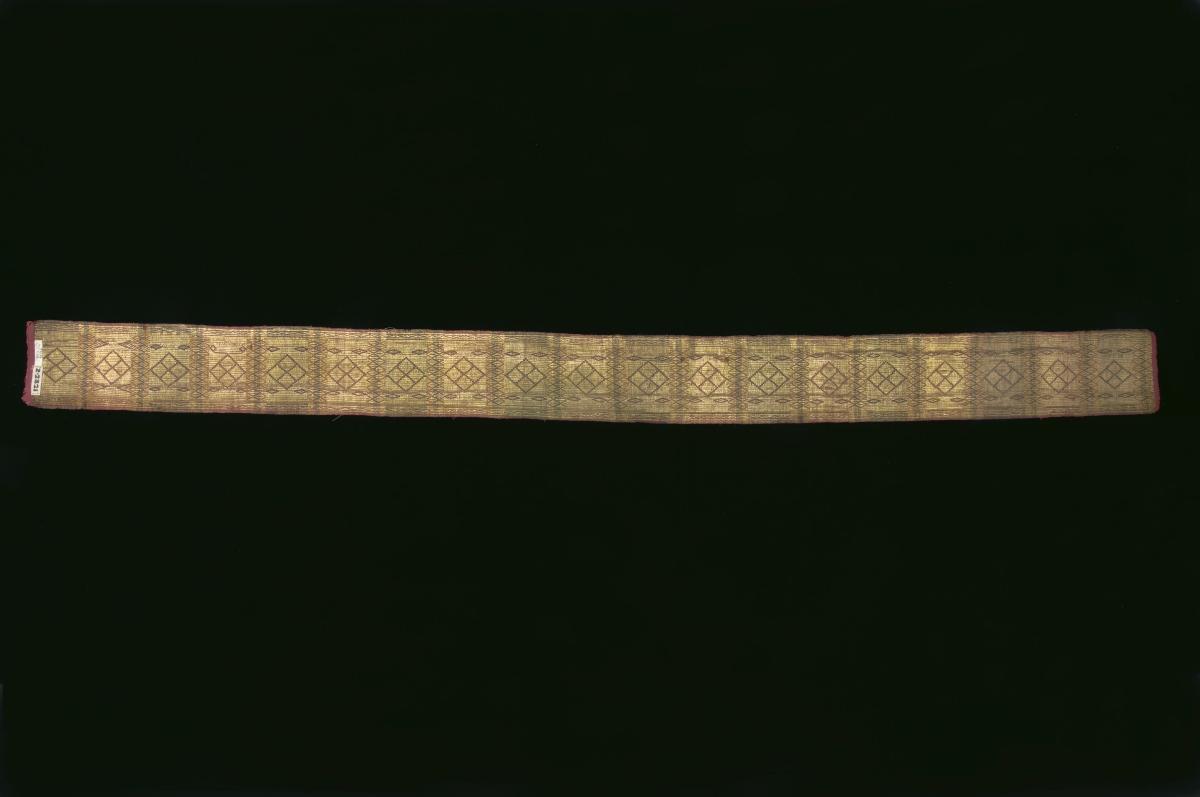

Trade with India also left its mark in the textile traditions of the wealthy elites. Large Indian trade cloths of the 17th century – the precursors of later batik designs – were worn by aristocrats, whilst the sumptuous songket weaving tradition produced shimmering cloths of gold that are still highly prized today.

Collection of the Asian Civilisations Museum.

Chinese Influences

It is difficult to pinpoint when Chinese traders and settlers first arrived in Sumatra. Chinese ceramics dating from the early centuries of the Common Era onwards have been retrieved from private collections. Archaeological evidence now shows that China traded directly with other countries as early as the 9th century. An Arab dhow that was salvaged at Belitung Island off southeast Sumatra carried a cargo of some 60,000 objects. These included mainly ceramics, as well as extremely rare gold and silver items thought to be official gifts for the courts in Iran (Persia).

Chinese presence in the region increased during the Ming dynasty (1368- 1644). Large expeditions by imperial envoy Zheng He cultivated tributary trade with Southern Ocean (Nanhai) countries during the 14th century. Migration from southern China increased particularly during the Colonial period when the Chinese ran businesses and worked for the administration as supervisors, tax collectors and tin miners.

Chinese settlement in coastal areas, especially Palembang, spawned successful alliances with the ruling elites. Inter-marriages resulted in the Peranakan, or ‘local born’ communities notable for their unique material culture that combines Chinese, local and European influences. Chinese lacquer-makers for example, were encouraged by the court to settle in Palembang where they became renowned. By 1813, one thousand Arabs and Chinese lived in Palembang. Their artistic traditions thrived as one of the court arts alongside ivory-carving, textiles and weapon-forging. Traditional symbols such as the phoenix and dragon (representing the Chinese empress and emperor, respectively), the fish (a symbol of fertility), the Chinese characters for happiness (fu), wealth (lu) and longevity (shou), and Buddhist emblems were in turn often adopted by other communities as decorative motifs.

The arrival of Islam

Islam was established in Sumatra during the 13th century through trade with Muslim merchants and the founding of the first Islamic kingdom at Samudra-Pasai in Aceh. Most of the coastal sultanates derived their heritage from Malayu, the ancient seat of the Srivijaya kingdom. They became wealthy through international trade conducted at coastal ports and the courts became centres for cultural exchange with Mughal India, China, Europe, Iran and other countries in West Asia.

Diverse cultural influences are evident in the different styles of Islamic architecture, textiles and the court arts patronised by the different sultanates. These items became royal regalia, the treasured heirlooms or pusaka that enhanced the legitimacy of rulers. They also included gifts from overseas which over time acquired legendary fame for their protective powers.

Foreign imports and skills from the Islamic World were highly valued. Silk and gold thread from India and China were used for royal garments, whilst Ottoman Turkish craftsmen sent to Aceh in the 16th century left a legacy of jewellery-making techniques. Diamonds and precious stones were imported from Persia and were brought from Kalimantan by Bugis traders. Keris-forging was introduced by the Javanese in the 13th century as well as by Bugis traders from South Sulawesi who travelled extensively and settled in the port areas of Sumatra.

Collection of National Museum of Indonesia.

Regional Exchanges between the Coast and the Central Highlands

Regional exchanges of cultural influence also took place between remote communities in the interior and coastal trading centres. Highland communities required metals for tools, jewellery and ritual objects, porcelain, salt and cloth. Coastal traders sought gold and natural products from the forests, and relied on the highlanders to transport these commodities via rivers or difficult land routes to the coast.

The Batak of Sumatra’s northern islands have ancient Hindu-Buddhist connections with early Indian settlers who moved into the interior from coastal regions. By the 19th century they had adopted Islam from Minangkabau and Aceh. However religious practices still combine ancestor worship and animistic rituals. These streams of influence are reflected in the motifs and designs of their jewellery, sculpture and other ritual objects.

Although more remote, the islanders of Sumatra’s west coast such as the Nias community also traded with their neighbours. Gold was an important part of the jewellery tradition patronised and worn by the Nias nobility. The nobles distinguished themselves from commoners and slaves by commissioning gold jewellery, which is also seen in the carved adornments on wood figures of the ancestors.

Collection of Mark Gordon.

Ideas from the West

Europeans had known about Sumatra since Marco Polo’s visit to the island’s northern coast en route from China in the late 13th century. The Portuguese and Dutch arrived in the region during the 16th and 18th centuries respectively. However it was not until the 19th century that Dutch influence was consolidated in Sumatra. The 1824 the Anglo-Dutch Treaty signed between the Dutch and the British finally resolved conflicting interests in the region, including the role of Sir Stamford Raffles, who had been Governor of Bencoolen (1817 – 1823). One of the terms of the treaty resulted in the exchange of Sumatra for Dutch interests in the Malay Peninsula, including Singapore.

European trade for the most part was done with coastal communities, who sourced the much wanted pepper, gold, camphor and benzoin from the hinterlands. However, European influence also left its mark both on the courts as well as remote tribal communities. Christianity found its way to the Batak highlands from the 1860s onwards and Lake Toba, the ancestral homeland of the Batak, only first visited by Europeans in the late 19th century.

Local arts and crafts were also influenced by European interests. Objects collected during scientific expeditions and commissioned specially for large international exhibitions held in Europe during the late 19th century, included pieces made in European taste. The legacy of collecting was maintained through museums, the new cultural storehouses. The ‘colonial gaze’ or way of perceiving local cultures still underpins some museum displays today, and could be said to be yet another stream of cultural influence that fostered the rich heritage of Sumatra.

From 30 July till 7 November 2010, the exhibition Sumatra: Isle of Fold at the Asian Civilisations Museum was the culmination of a collaborative project between the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden, the Netherlands, and the National Museum of Indonesia with the support of provincial museums in Sumatra. The show travelled from Jakarta to Leiden before coming to Singapore. The Asian Civilisations Museum adapted the show to include more pieces from its own and private collections.

References

The publication Sumatra. Crossroads of Cultures. (Eds. Francine Brinkgreve and Retno Sulistianingsih, KITLV Press, Leiden, 2009) was published in association with the exhibition held in Leiden in 2009. It was on sale at the ACM museum shop together with an exhibition booklet Sumatra: Isle of Gold.