Mapping out early Singapore

As soon as the British arrived, they started building roads to support the rapid development of the new trading post. In the early years, place names were very practical in nature which gave rise to sites like Commercial Square, Market Street and Hospital Road.1

A view of Commercial Square during the 1860s. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

A view of Commercial Square during the 1860s. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

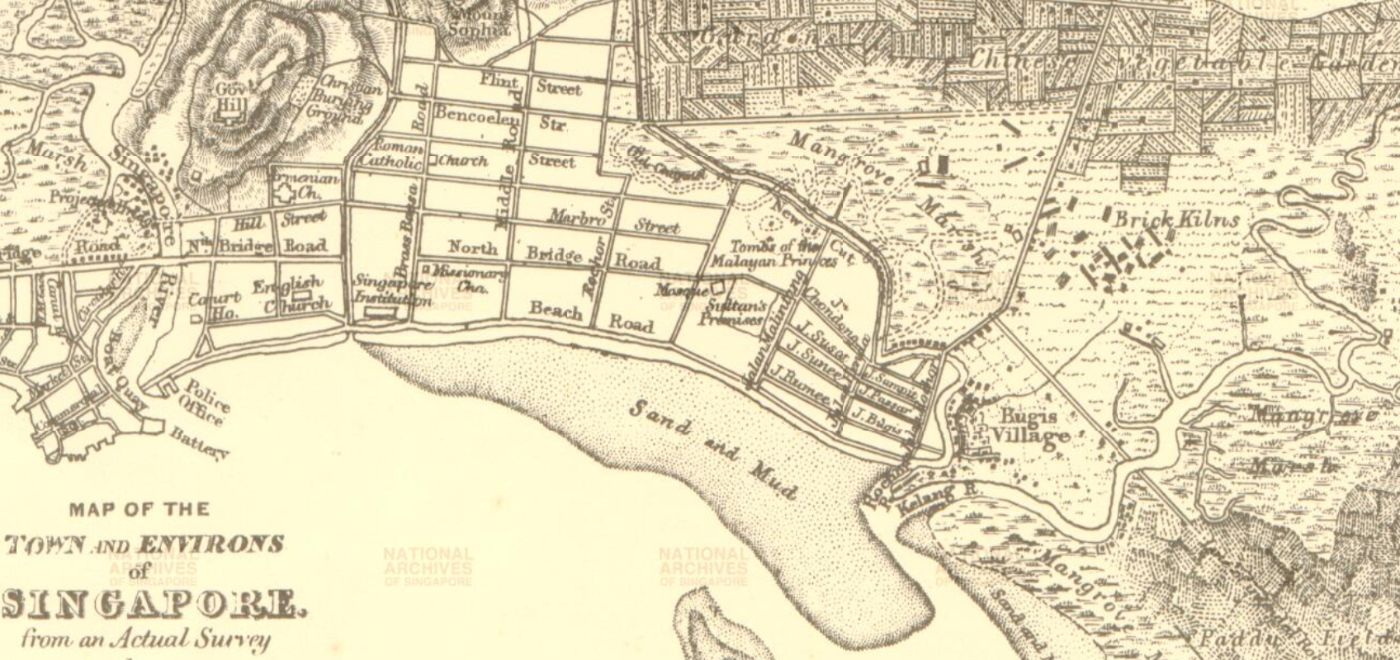

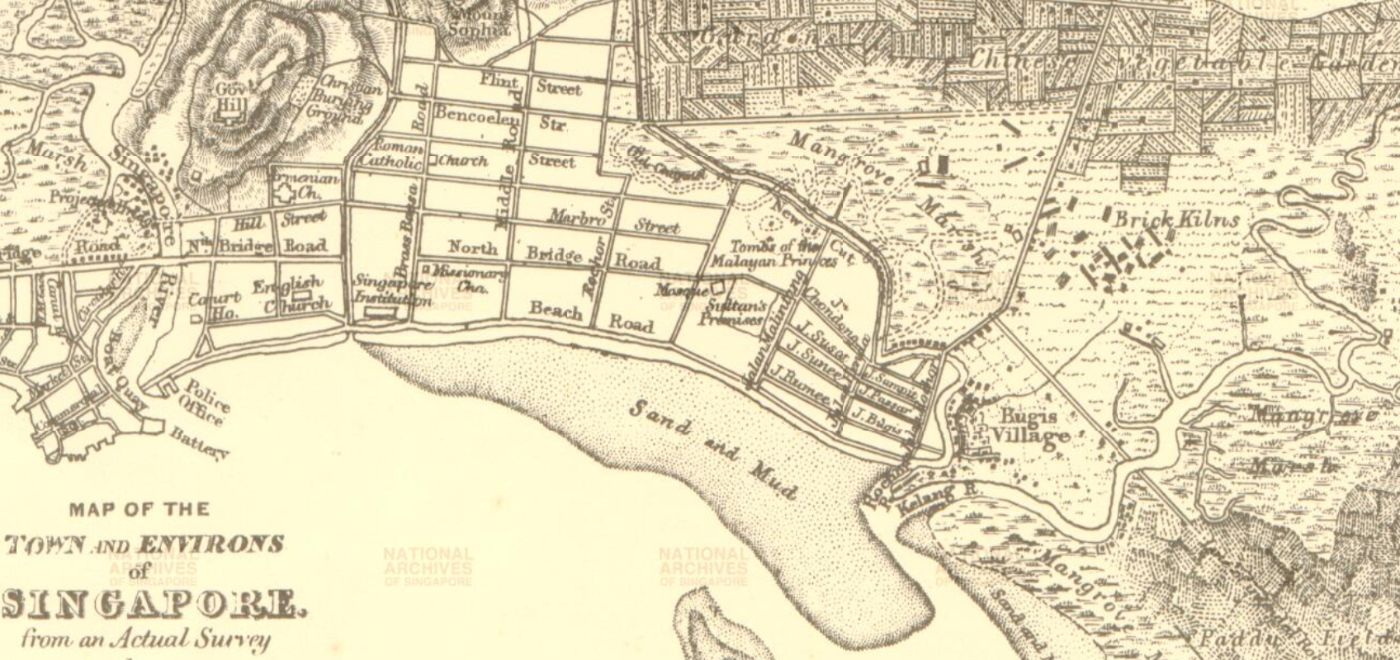

Irishman G. D. Coleman was assigned by the British to conduct Singapore’s first official topographical survey. Completed in 1829, the survey captures early road infrastructure such as Flint Street, Circular Road and Tanjong Pagar Road.2 (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

Irishman G. D. Coleman was assigned by the British to conduct Singapore’s first official topographical survey. Completed in 1829, the survey captures early road infrastructure such as Flint Street, Circular Road and Tanjong Pagar Road.2 (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

During subsequent stages of town planning, the city was divided into racial and occupational quarters, as per the instructions of Sir Stamford Raffles.3 Published in 1828,4 the plan comprised zones such as Kampong Glam for Bugis and Arabs merchants, land upstream of the Singapore River for the Chulias, and space southwest of the Singapore River for the Chinese.5 As the colony developed, marshes, swamps and jungle were cleared. In turn, more roads were carved out. Among them: Queen Street, Coleman Street and Pickering Street — all of which were named after prominent British figures and officials.6

The names of community leaders such as Lim Nee Soon (12 November 1879-20 March 1936) were also etched onto street signs. Lim, known for his rubber empire, has a record number of streets named after him — a staggering 26.7 Lim had acquired and leased large tracts of land along the Seletar River area within the boundaries of present-day Yishun, for his rubber business.7

In all, just 40 of 540 road names, as compiled in the book Toponymics: A Study of Singapore Street Names, are named after women. Jalan Hajijah is one of them. It was named after a heiress known as Hajjah Hajijah who founded a Malay kampung on land she had purchased off Upper East Coast Road.9 The kampung, likely established in the 1900s, had about 30 houses. It was demolished in the 1980s.10

Some place names reflected economic activities in the area. For instance, the cultivation of lemongrass plants gave rise to the name Geylang Serai. Serai means lemongrass in Malay.

It was the same for Dhoby Ghaut. Dhobis or laundrymen could often be found knee-deep in the freshwater stream now known as Stamford Canal washing bundles of garments. The washermen utilised a plot of land nearby to dry the clothes. Ghaut or ghatin in Hindi refers to the area along a riverbank used for bathing or washing.

A 2ha plot of land (on the right) where dhobis (washermen) dried their clients’ laundry.

A 2ha plot of land (on the right) where dhobis (washermen) dried their clients’ laundry.

The local populace put their own spin on some of these assigned names. For instance, they preferred to call Chinatown’s Kreta Ayer (water cart in Malay) goo cia chwee in Hokkien. The name translates to “bullock cart water”, a direct reference to the bullock carts which used to supply the area with fresh water.11

Within British military camps and compounds, roads were named after famous British streets. Some posit that it was a way to help servicemen deal with homesickness.

We’ve also “borrowed” place names from the region resulting in Tanjong Katong’s Ipoh Lane (Malaysia), Bencoolen Street (Indonesia) in the Bras Basah area, Little India’s Madras Road (India), as well as Mandalay Road (Myanmar) in Novena.12

Post-independence naming conventions

Singapore began to shape its own toponymic policies after independence and the decision was made to retain colonial-era road names.13 It was too disorienting to do an overhaul. It also did not make much sense to wipe out Singapore’s past in one fell swoop.14

Nonetheless, an advisory committee for the naming of roads and streets established in 1967, suggested modifications to existing public street names to foster a sense of national identity.15 Malay place names, for instance, were recommended, which explains the city’s jalans and lorongs.16

A year later, a committee to standardise street names in Chinese, and to provide English translations for Chinese and dialect place names, was set up.

Overtime, the authorities gave prominence to local culture and heritage, as well as leaders and public figures who were integral in influencing Singapore’s post-independence trajectory.

For instance, newfangled structures such as a $110 million bridge, which opened in 1981 as part of the East Coast Parkway, was named after Singapore’s second president Benjamin Sheares.17

Furthermore, Singapore’s pool of languages was tapped to reflect the city’s multicultural makeup. Take the case of Jurong industrial estate: the area is home to Fan Yoong Road (prosperity, in Mandarin), Neythal Road (to weave as clothes, in Tamil), and Jalan Tukang (skilled craftsman, in Malay).

In 2003, the Street and Building Names Board was established.18 It vets and approves the naming and renaming of buildings, estates as well as streets proposed by building owners and developers. In 2010, the Urban Redevelopment Authority took over its secretariat role.

The Street and Building Names Board encourages the retention of heritage in naming sites to “reinforce a greater sense of history and identity among the community”. The 2009 decision to name a street leading to the School of the Arts in Dhoby Ghaut as Zubir Said Drive, after the composer of Singapore national anthem, reflects just this. The board also prioritises names which can help emergency services locate places fast.19

Old street names, remarkable stories

Lavender Street

A view of Lavender Street in the late 19th to early 20th century. This street reeked due to the liberal use of night soil as fertiliser by the owners of vegetable gardens in the area.20 The name Lavender was picked for the site in 1858 as an ironic nod to the pungent odours it had come to be known for.21 (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

A view of Lavender Street in the late 19th to early 20th century. This street reeked due to the liberal use of night soil as fertiliser by the owners of vegetable gardens in the area.20 The name Lavender was picked for the site in 1858 as an ironic nod to the pungent odours it had come to be known for.21 (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

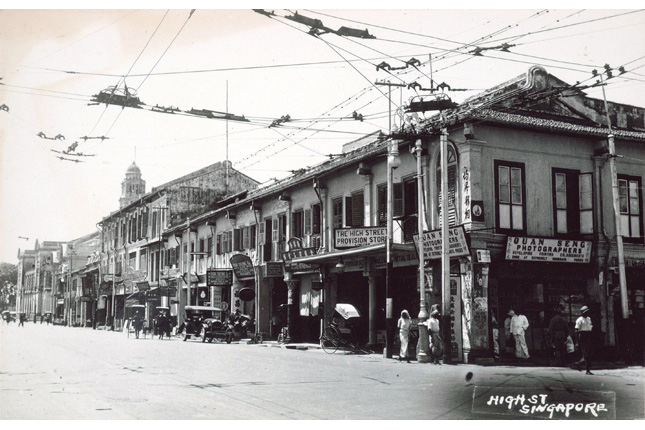

High Street

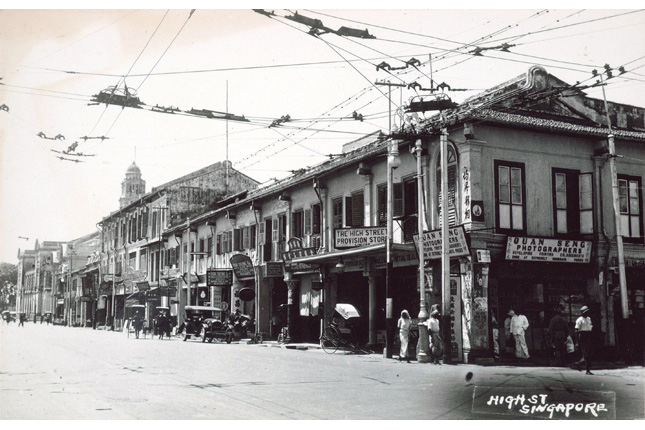

This is likely the oldest street in Singapore. It was developed after Sir Stamford Raffles’ landing in 1819 and named as such due to its topography.22 It also once served as a high-end shopping stretch.23 (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

This is likely the oldest street in Singapore. It was developed after Sir Stamford Raffles’ landing in 1819 and named as such due to its topography.22 It also once served as a high-end shopping stretch.23 (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Beach Road

Once a coastal stretch, Beach Road appears in G. D. Coleman's 1836 map of Singapore. It was originally set aside for European merchants.24 (c. Late 1970s. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Once a coastal stretch, Beach Road appears in G. D. Coleman's 1836 map of Singapore. It was originally set aside for European merchants.24 (c. Late 1970s. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Coleman Street

Coleman Street was named after Singapore’s first pioneer colonial architect who shaped early Singapore’s look. G. D. Coleman designed the Old Parliament House (The Arts House today) and the Armenian Church, among other landmark buildings. He was also responsible for the first topographical survey of the island. His house once stood along No 3. Coleman Street. It was demolished in 1965 and replaced by the present-day Peninsula Hotel.25 (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Coleman Street was named after Singapore’s first pioneer colonial architect who shaped early Singapore’s look. G. D. Coleman designed the Old Parliament House (The Arts House today) and the Armenian Church, among other landmark buildings. He was also responsible for the first topographical survey of the island. His house once stood along No 3. Coleman Street. It was demolished in 1965 and replaced by the present-day Peninsula Hotel.25 (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Syed Alwi Road was originally called Syed Allie Road after the Arab merchant Syed Allie Bin Mohamed Al Junied. Syed Allie gave back to the community generously by donating land for community purposes and building large wells.26 (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Syed Alwi Road was originally called Syed Allie Road after the Arab merchant Syed Allie Bin Mohamed Al Junied. Syed Allie gave back to the community generously by donating land for community purposes and building large wells.26 (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Pickering Street

Originally Macao Street and Upper Macao Street, and the site of the original Chinese Protectorate,27 this road in the downtown core of Singapore’s central region, was renamed to honour the contributions of William Alexander Pickering who, as the head of the Chinese Protectorate, helped clamp down on coolie abuse and rein in Chinese secret societies.28 He could speak Mandarin and four Chinese dialects, winning the hearts of members of the Chinese community.29 (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Originally Macao Street and Upper Macao Street, and the site of the original Chinese Protectorate,27 this road in the downtown core of Singapore’s central region, was renamed to honour the contributions of William Alexander Pickering who, as the head of the Chinese Protectorate, helped clamp down on coolie abuse and rein in Chinese secret societies.28 He could speak Mandarin and four Chinese dialects, winning the hearts of members of the Chinese community.29 (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

North Bridge Road

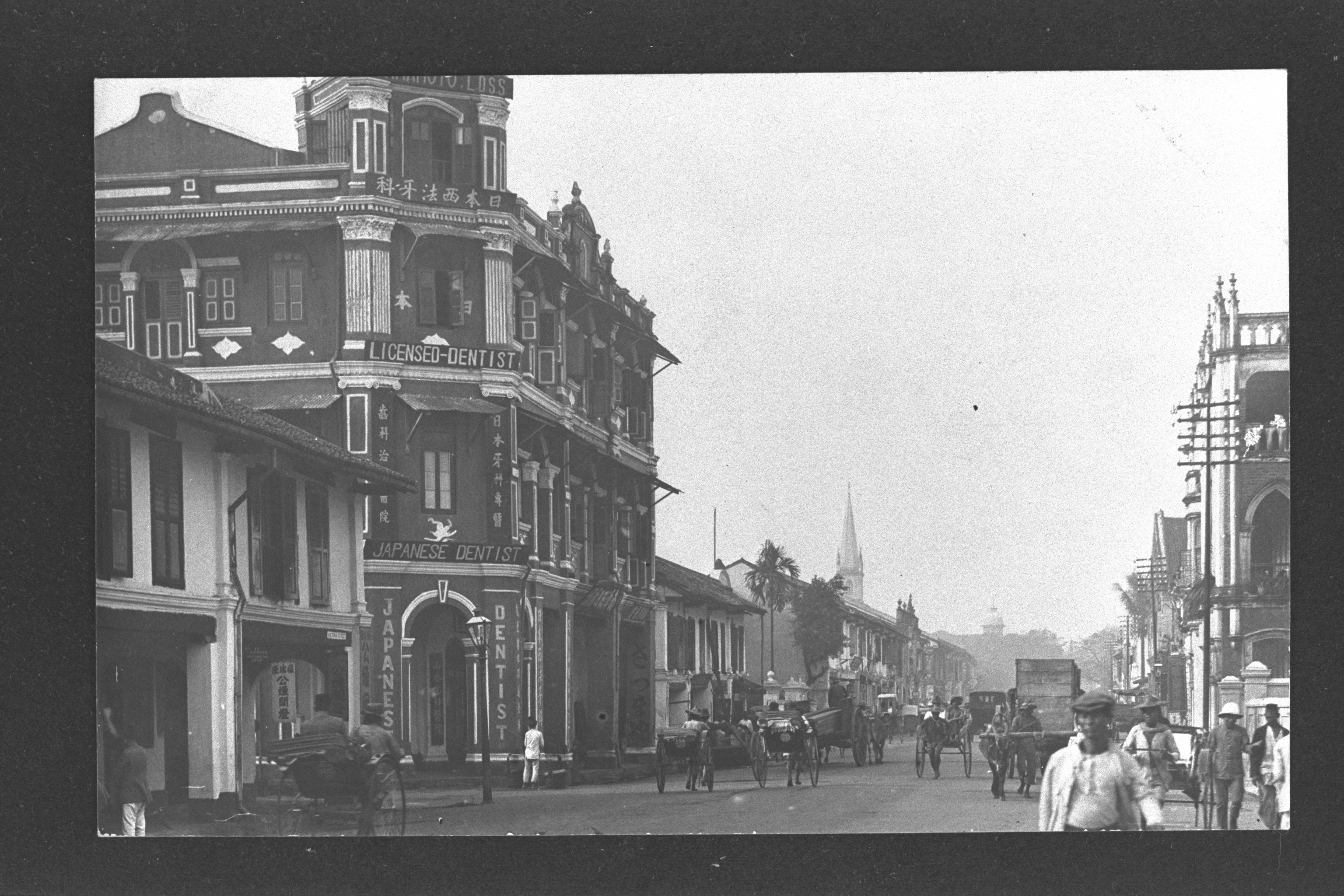

One of the earliest and longest roads in Singapore, North Bridge Road was named as such as it lies north to Elgin Bridge which spans the Singapore River. Its sister road, South Bridge, was part of Sir Stamford Raffles’ 1822 Town Plan. Both were built by convicts.30 (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

One of the earliest and longest roads in Singapore, North Bridge Road was named as such as it lies north to Elgin Bridge which spans the Singapore River. Its sister road, South Bridge, was part of Sir Stamford Raffles’ 1822 Town Plan. Both were built by convicts.30 (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Mosque Street

Mosque Street, a one-way street in Chinatown, was named as such due to the presence of Jamae Mosque which was built between 1830 and 1835 by Chulia Muslims. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Mosque Street, a one-way street in Chinatown, was named as such due to the presence of Jamae Mosque which was built between 1830 and 1835 by Chulia Muslims. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)