By Vidya Murthy, Researcher, National Museum of Singapore

Images: National Museum of Singapore

BeMuse Volume 3 Issue 3 - Jul to Sep 2010

On January 23, 1931, twenty-five year old Ng Chen committed suicide. He was a laksa hawker living in Duxton Road. On hearing of this tragic incident, Seow Poh Leng, a concerned citizen, wrote an eight stanza poem in his article, “The Hapless Hawker: A Plea for Humane Treatment”1. Making no claims to its literary merit, Seow hoped that his verse would “invoke the sympathy of the powers-that-be and of the public for voiceless, illiterate and the much-maligned Hawkers.” First printed in the Malaya Tribune, the article is included in the Report of the Committee Appointed to Investigate the Hawker Question in Singapore, 1931 (hereafter referred to as Report):

"We came from Cathay, the land of ancient renown

To try and earn a living in this far-famed modern town

Though father and mother are old they still have to toil each day

My father selling bean-curds, mother selling “kway” [sic]

.....

Good-bye my parents dear, good bye my kith and kin!

Think not the step I take an unpardonable sin

I’ve not forgotten the lesson of filial piety’ . . .

Rather than become a criminal and sully the family name

I drink this potion dark and prefer even death to shame."

II

In the early 1900s, a cup of coffee with milk cost two cents on the street and three cents in a coffee shop. Satay sold on the five-foot way was about two cents a stick, and a bowl of Hokkien mee was ten cents. Every cent mattered then, because in 1908, a coolie earned about fifty cents and a rickshaw puller about two dollars a day. Rents for a cubicle on Sago Lane ranged from one and a half to four and a half dollars a month2. In the 1920s, with a capital of fifty cents, one could make about twenty cents3. But this money was hardly enough and by the 1930s, with the depression, the plight of the street hawkers was bad. For instance, in 1935, Liew Ah Chow was in distress as he could not afford medical treatment for his daughter. As a cobbler, he made about thirty to forty cents a day. On this money, he could not afford the ten dollars that the General Hospital charged as medical fees.

Documents such as the Report show the ways in which the administrators viewed the hawkers – as a problem that needed to be addressed. It appears that the main objections to the hawkers, especially the food vendors, were that they caused health problems through serving contaminated food, littered streets, obstructed traffic, posed unfair competition to shop keepers, corrupted the lower ranks of the Police and Municipality and were suspected to having connections with the Secret Societies.

The authors of the Report recognised that the hawkers were essential and that it was a means of livelihood, especially for the new immigrants4. They helped to distribute goods including fruits and vegetables for the retailers and provided cheap and efficient services. So, according to them, a total abolishing of these hawkers was not ideal, but it was important to reduce their numbers, keep them off the main streets and house them in dedicated shelters. Thus their recommendations involved controlling, regulating and monitoring the hawkers. One of the chief ways of doing this was through issuing of licenses.

The first proposal to license and set aside designated places for peddlers to hawk their wares was made in 1903 and it was at the behest of the Chinese Protectorate and the Municipality. The reason for this was that the Police found the hawkers a nuisance and an obstruction on the streets. In 1905 the Municipal Commissioner suggested that food hawkers must be registered. Following this, a series of regulations were instituted. This included licensing of Eating Shops and Coffee Houses in 1913 and the itinerant hawkers both by day and night in 1919.

Itinerant hawker's license no. 6017, issued to Yeo Jeah Siang, 1948.

Itinerant hawker's license no. 6017, issued to Yeo Jeah Siang, 1948.

The three institutions that were involved in ‘solving’ the hawker issues were: Police, the Municipality and the Health Officers. While the Health officers made stringent demands, the Police penalised offenders by seizing their goods and paraphernalia. Not all the rules were successful. Many stallholders who could not meet the health standards closed their shops. As a result, there was an increase in food hawkers on the streets. In 1931, at the time the Report was made, there were 6,043 licensed itinerant hawkers and an estimated 4000 unlicensed ones on the streets. There were six shelters housing 383 hawkers.

III

The colonial Report reveals the attitudes of the local elites and citizens such as Seow Poh Leng mentioned above. Included are the opinions of the members of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, Teochew guilds, and the Straits Chinese British Association among others. While some favoured and sympathised with the hawkers and questioned the efficacy of licensing, others demanded that the hawkers be removed.

Note for instance the opinion of R. Krishnan, editor of The Indian and representing The Indian Association5. He wanted the Indian ice-water seller off the streets. “I have no sympathy for him,” he says. “If he cannot be removed instantaneously, there should at least be a policy aiming at a quick abolition of this kind of hawkers. . . . Get hold of any ice-water hawker and inspect his fingers. And what do we see? Inflammation of his nail beds and not infrequently pus exuding from them... And it is with such fingers that he prepares his syrups or produces “ice-balls” for innocent school children! Again he is the root cause of the dental caries and gastric disturbances of the school going children in Singapore at least that is the strong feeling of Indian parents.”

Krishnan does not spare the tea and ginger bun sellers, curry puff sellers, vendors of agar-agar or the curd sellers, all of whom belonged to various Indian communities. This perception that the food preparer and seller is an agent of disease is unequivocally established in a language of modernity6. If it resembles the attitude of the colonial administrator, it is not a co-incidence. His fear of contamination is not restricted to the seller but to the consumer as well. In a language that reads like a public health nightmare, he writes of the practice of eating off the same plate, “Incidentally the habit of eating off the same dish or plate, as a “satay” sellers’ table or at a Chinese stall contributes to the speedy spread of infections from one mouth to the other . . . that dreadful disease, syphilis, will easily, once the infection is passed, go the rounds by this means.”

In contrast to this negative perception, the itinerant traveller and photographers cast the street peddler as an exotic being. Moving the peddler out of the street and into the studio, the photographer posed him with the tools of his trade. Although removed from the grit and grind of labour, the hawker is presented as an embodiment of work. The picturesque effect becomes even more pronounced in the commercial prints and postcards that began to be produced for bourgeoisie consumption.

If the colonial photographer sought to romanticise the hawker, the adventure seeker was not far behind. In a 1931 account, a street barber is described in the following manner, “The barbers sit along the sidewalks, and in addition to shaving your face, a barber scrapes your tongue, and the same water is used over and over again. He also, with funny little instruments, cleans your eyes, ears and nose”7. These remarks are revealing. Despite the fascination of the Orient, the traveller cannot help but reveal his own deep-seated cultural attitude to dirt and hygiene.

Barber, 1938.

Barber, 1938.

Barber

Barber

IV

Who were the street peddlers? What became of them? These questions might never be fully answered as there are no first person accounts available. There are various types of sources that explore the economic and social conditions of street life in the late 19th and early 20th century. Among them are histories of the working class, accounts left behind by travellers, and colonial records. Following the classic 1963 study by the anthropologist, Clifford Geertz, economists and city planners began to take notice of street traders8. Economists have examined street hawkers in urban cities such as Hong Kong and Jakarta among others9.

The studies of Singapore’s street peddlers, especially food vendors, have to be located in the corpus of this larger discourse10. Visual records such as drawings, illustrations and fictional representations of the working class can also be considered. For instance, classic studies such as Samuel Victor Contant’s 1936 work Calls, Sounds and Merchandise of the Peking Street Peddlers is a wonderful study which analyses the language the hawkers’ use and carries charming coloured drawings.

The well-known novel, Rickshaw (Lo-T’O Hsiang Tzu), set in Shanghai in the turn of the century, offers a compelling portrait of misery and destitution of street workers and their lives11. However, such an account of Singapore’s street people in the early 20th century is yet to be written. Still, there exists, in the National Museum collections, a wealth of materials including photographs, postcards and some associated material culture such as tools and objects.

Peddling of goods and services in the late 19th and early 20th century was tied to migration and kinship networks. Predominant among the street hawkers were the Chinese, Indians, Malays and some Jews. The Chinese were identified largely by their dialect groups included the Cantonese Hockchias, Hockchius, Hokkiens, Shanghainese and Teochews among others. They sold coffee, cooked food, fresh produce, fish, and meats such as pork. Among the Cantonese, there were also women who took to peddling goods, toys, and cigarettes. The Shanghainese sold silk.

Peddlers from the Indian communities sold bread, fried snacks, yoghurt, milk and iced-water.

Street side hawkers selling bread, c. 1940.

Street side hawkers selling bread, c. 1940.

Donated by Mr. Thomas Kennett

Among the people of the Malay Archipelago, the Javanese peddled curios and cloth, while the Malays sold satay. Although the hawkers could be found all over the town as some of were itinerant, many of them operated in the central areas. These areas specified by the municipal authorities included largely the southeast part of the island around the Singapore River. The hawkers tended to work along common dialect or language groups.

For instance the Hokkiens who were the largest group of Chinese hawkers could be found everywhere especially around China Street, Hokkien Street and Telok Ayer Street. That they mostly operated in the municipal areas became a major sore point with the colonial administrators.

Chinese Street, Singapore

Chinese Street, Singapore

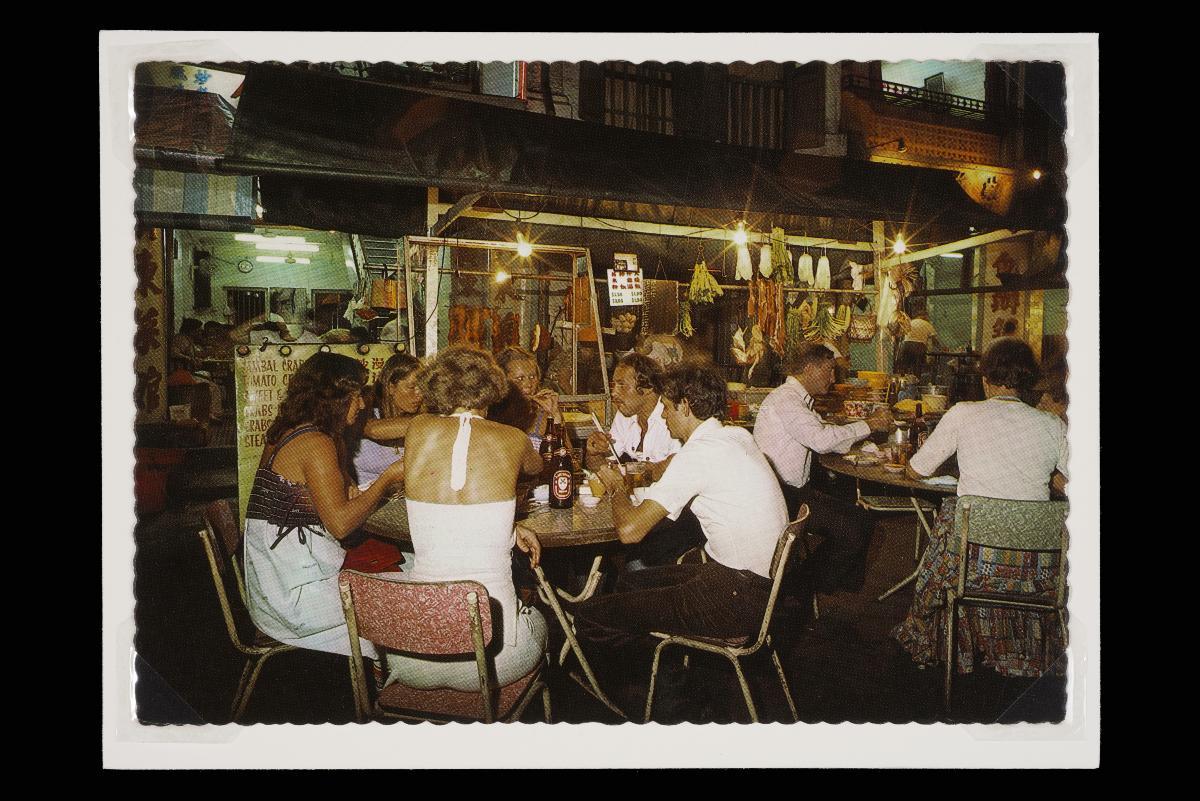

The exhibition, Surviving the Streets: Peddlers and Artisans in Early-Mid 20th Century Singapore, was about these people who made a living on the streets and five-foot ways. Their lives on the streets highlighted not only disparities between class and race but also the conflicting perceptions between the colonial government and the people. However, through their day to day economic transactions, these individuals forged lasting relationships among themselves and with the spaces in which they operated. That is, the exhibition attempted to define peddlers as not just producers of work. Instead through a selection of artefacts including tools and images of leisure, the display hoped to show that the street vendors were social beings who transformed the world they inhabited in meaningful ways

Surviving the Streets: Peddlers and Artisans in Early-Mid 20th Century Singapore was an exhibition curated by the author. It was on at the Balcony, National Museum of Singapore from 28 June to 22 August 2010. More than a hundred artefacts drawn from the National Museum’s collections were displayed along five themes: The Street and the Image, Artisans and Tools, Postcards and Peddlers, Services, Leisure and Social Life. Three video footages of craftsmen, two audio clips of interviews and a selection of folk songs were also included in the display.