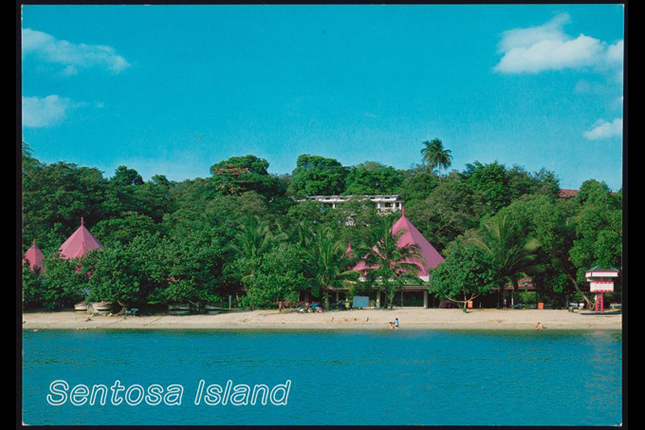

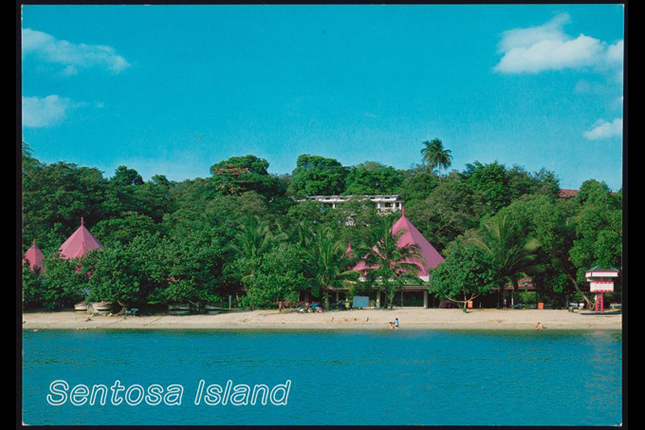

Lagoons and chalets line the beach of Sentosa following its transformation into a tourist attraction. (c. Mid-1970s. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Lagoons and chalets line the beach of Sentosa following its transformation into a tourist attraction. (c. Mid-1970s. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Pirates, villages and forts

Located off the southern coast of Singapore, the 500-hectare island we know as Sentosa today, used to be called Pulau Blakang Mati from as far back as the 1600s.1 Its name translates to “the island behind which lies death”, possibly a result of brutal pirate battles of yesteryear.2

Ferry service on Pulau Blakang Mati as photographed in 1915. Image from National Museum of Singapore

Ferry service on Pulau Blakang Mati as photographed in 1915. Image from National Museum of Singapore

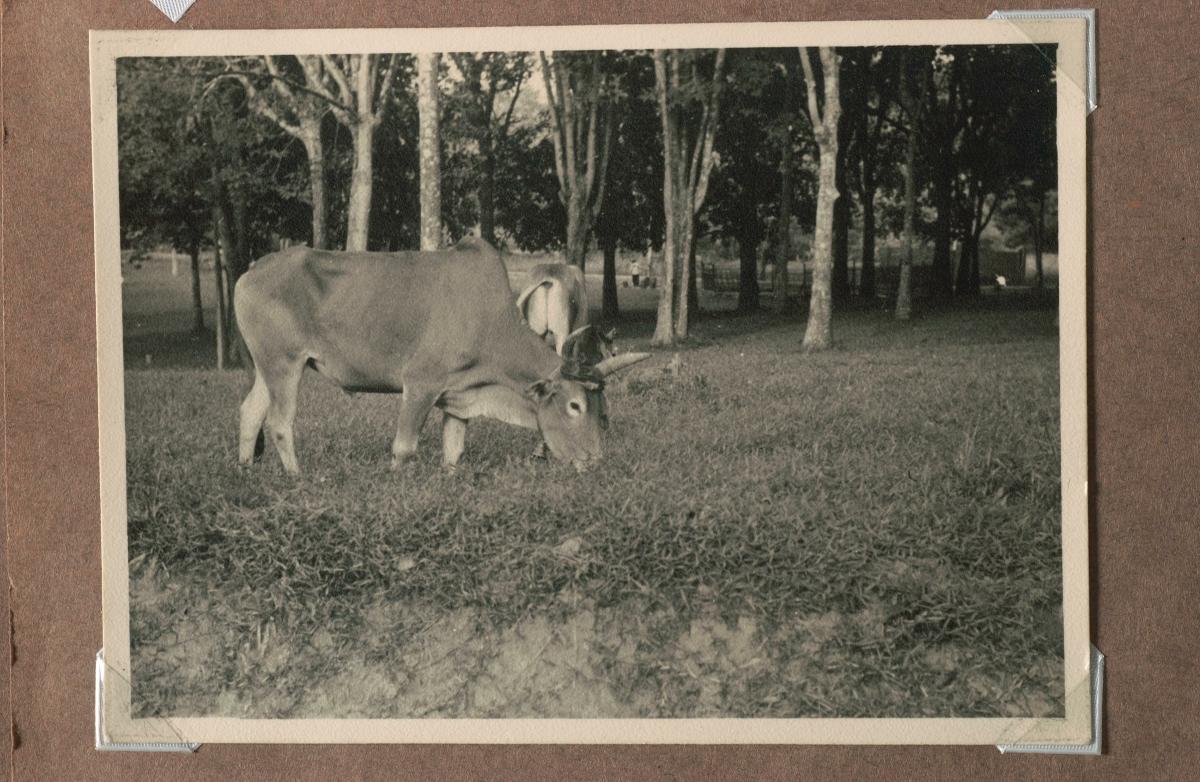

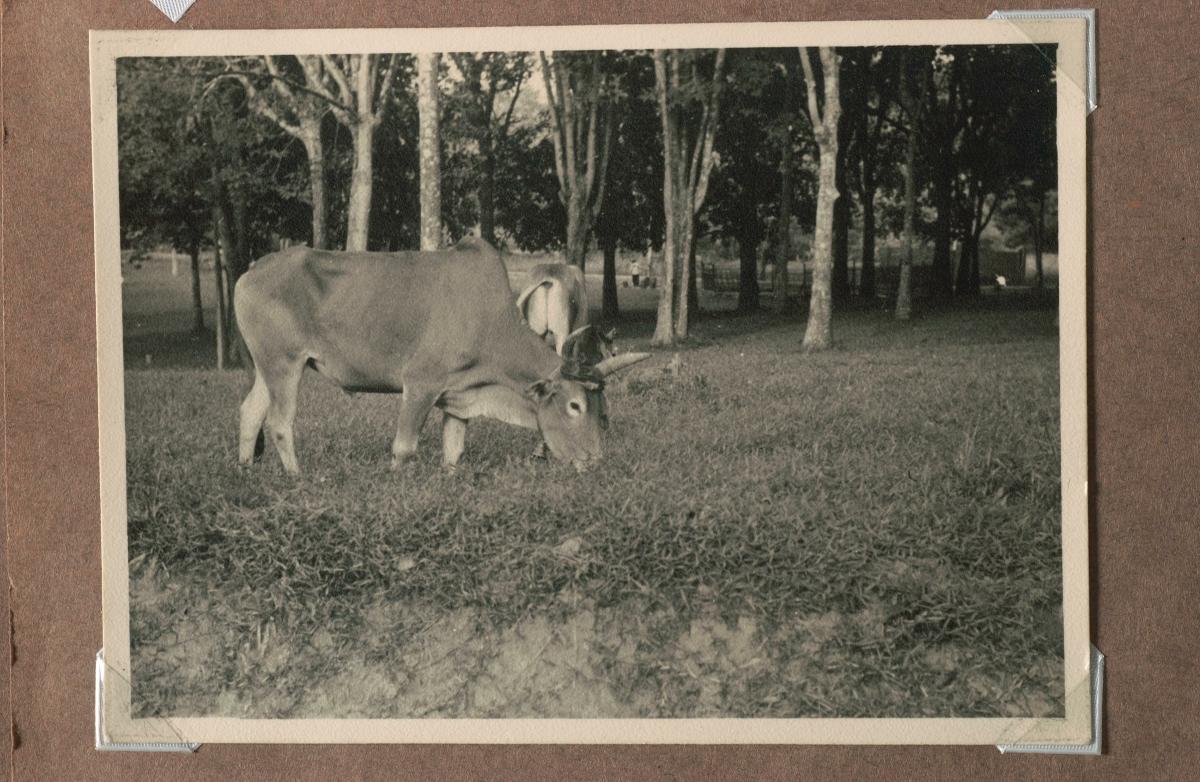

A pastoral scene (right) taken between the 1920s and 1950s. Image from the National Museum of Singapore

A pastoral scene (right) taken between the 1920s and 1950s. Image from the National Museum of Singapore

During the colonial era, a mysterious epidemic wiped out staff working at a British signal station.3 British doctor Robert Little who attended to the ill on the island in 1848, documented the existence of three villages inhabited by Malays, Bugis and Chinese.4They were: Kampong Ayer Bandera, Kampong Serapong and Kampong Blakan Mati. The doctor added that the island was home to various plantations among which pineapple was the most prevalent. Blakang Mati, he added, was "one vast pinery, supplying the island of Singapore with this delightful and refreshing fruit".

The island by and large served as a military base during the colonial era. To guard the eastern and western entrances of the harbour, Forts Serapong, Connaught and Siloso, as well as the Mount Imbiah Battery were installed in the 1870s and 1880s. In the 1930s, the British added guns with the ability to pierce through armoured ships. Royal Artillery units also moved in.

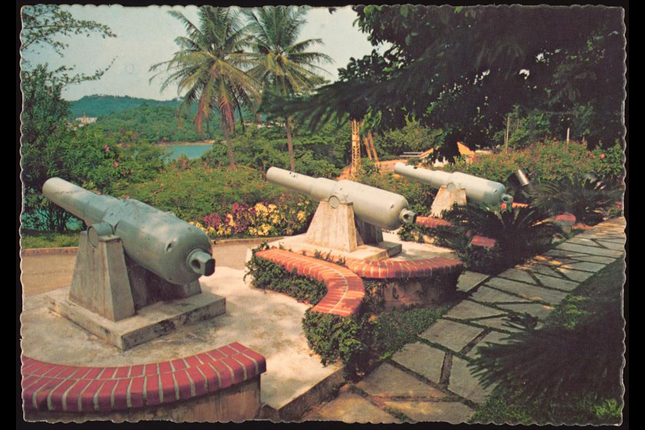

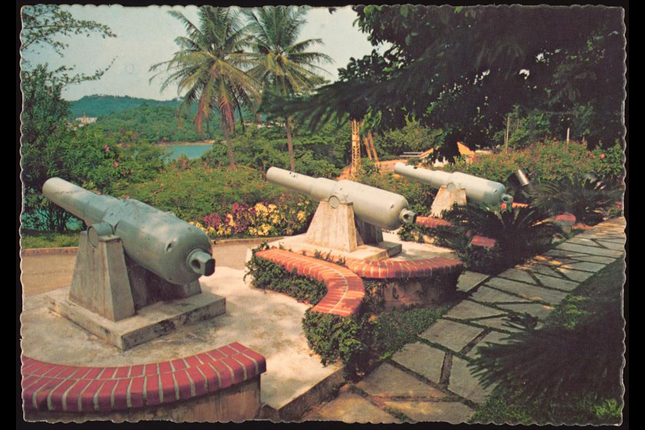

British guns at Fort Siloso photographed in the mid-1970s. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

British guns at Fort Siloso photographed in the mid-1970s. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

British personnel on Blakang Mati were served by dhobis (Indian laundry workers) and Chinese cooks. For leisure, they boarded sampans for the mainland where they could pay for a dance with a cabaret hostess at one of Singapore's three amusement parks, or enjoy a steak at one of the cafes around Victoria Street.7

The Royal Garrison Artillery barracks at Blakang Mati which comprised a parade square, housing quarters for military personnel, a church, grocery shop and small cinema, among other amenities. (1915. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

The Royal Garrison Artillery barracks at Blakang Mati which comprised a parade square, housing quarters for military personnel, a church, grocery shop and small cinema, among other amenities. (1915. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

A dark episode

Contrary to popular belief, the military installations on Blakang Mati were not completely useless in the Battle of Singapore for they were used to fire on targets in the centre, west and north of Singapore. In fact, the Japanese perceived the fortifications as a threat which explains the air raid of 18 January 1942 when 100 bombs were dropped on Blakang Mati.8

Shortly after the invasion, the Japanese rounded up Chinese men and had them executed in remote locations around Singapore. In 1957, eight skulls and almost 100 bones were found in one of Blakang Mati’s creeks — likely the remains of Chinese men who had worked at the Singapore Harbour Board.9

During the occupation, Blakang Mati housed a prisoner of war camp for about 1,000 allied troops. One prisoner, Sergeant Thomas A. Dineen, was a radio hobbyist who cobbled together a radio receiving set from odds and ends like silver paper and wire. He discreetly disseminated news of Allied victories elsewhere in the world to keep morale up among fellow prisoners.10

A rare World War II map of Singapore by the Japanese which points out key infrastructure and areas of interest including Blakang Mati at the bottom. The map was published during the war by news agency Tokyo Nichinichi Shimbunsha. (c1942. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

A rare World War II map of Singapore by the Japanese which points out key infrastructure and areas of interest including Blakang Mati at the bottom. The map was published during the war by news agency Tokyo Nichinichi Shimbunsha. (c1942. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

After the war, various British military units, as well as the Gurkhas, reoccupied Blakang Mati.

The civilian population also grew in numbers, as did economic activity on the island in the form of shops and services. Schools and religious institutions sprung up as well.11

Mainland visitors were drawn to Blakang Mati. Some brought with them fishing rods for a day out in the sun, others spent the night there, camping along its coast and making friends with villagers.12

“Battle” for the island

In 1967, Blakang Mati was officially parked under the jurisdiction of the newly independent government of Singapore13 which was understandably excited about its potential. The ministry of defence wanted to place security guns there, while other agencies envisioned a petrochemical complex or oil-related industrial hub. A few suggested it take on new life as a tourist resort.14

The plan to start an oil refinery was given legs when the government reached an agreement with energy corporation Esso. However, Albert Winsemius, an economic advisor to the government, as well as Alan Choe who was at the helm of Singapore’s Urban Renewal Unit (now the Urban Redevelopment Authority), convinced Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew that it was better to turn the island into a resort for recreation and tourism.

The potential air pollution from having an oil refinery so close to the city centre might have pushed the authorities to ultimately choose to retain Blakang Mati as a holiday island cum green lung.15 The deal with Esso was renegotiated and the refinery was eventually built in Jurong, further from the heart of the city.

A suggestion to turn Blakang Mati into an industrial complex with deep water berths was also shelved following a study which found heavy shipping traffic along the island's coasts too challenging to work around.16 Other sites which had been vacated by British forces, were allocated for such purposes instead.17

Building paradise

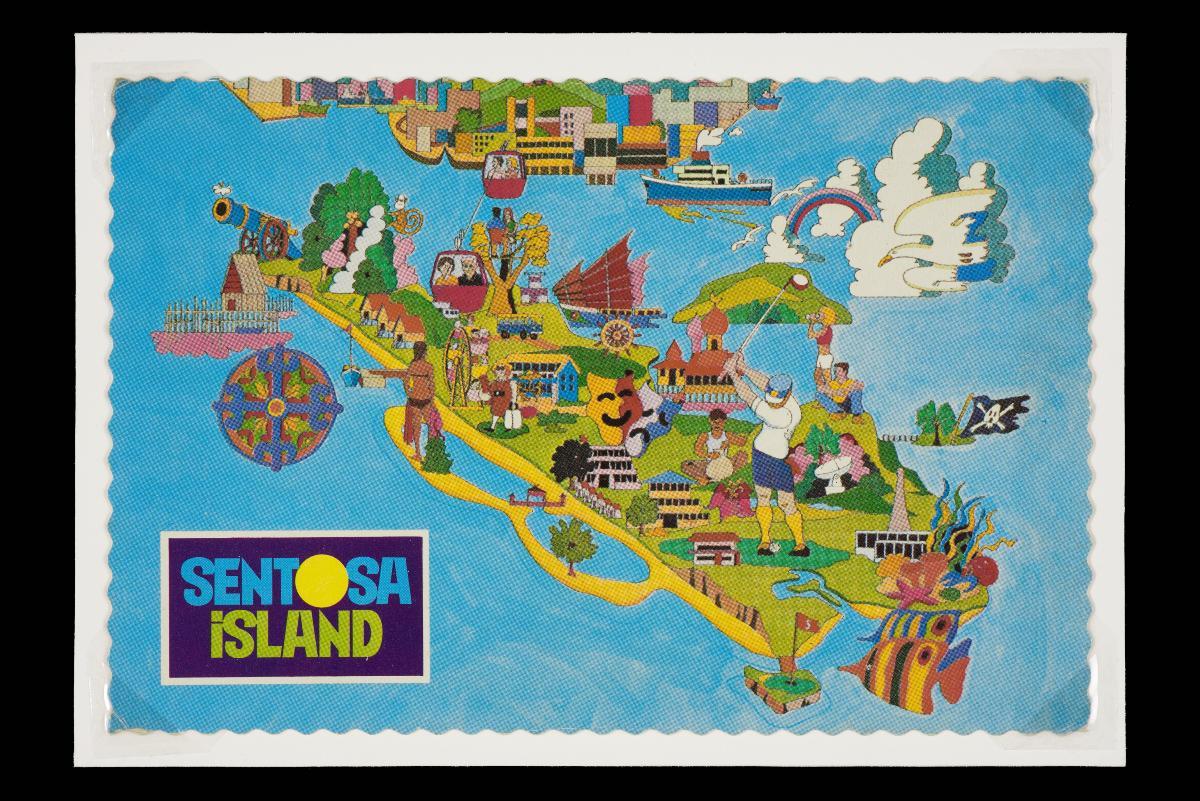

In January 1969, the chairman of the Tourist Promotion Board of Singapore, P. H. Meadows outlined plans to build a dreamy “south sea island paradise” with chalet-like hotels as well as golf courses and parklands. There too would be the option for scuba-diving and horse-riding. The goal, he shared, was to "attract millions of sunseeking tourists from all over the world”.18

To this end, the Tourist Promotion Board launched a naming contest to rebrand the site.19 The isle of tranquillity, or Sentosa in Malay, was eventually selected — a stark contrast to the ominous sounding Blakang Mati.

By 1972, $124 million worth of state money and private sector investment had been set aside for the resort’s development. Sentosa Development Corporation was established the same year to oversee the massive undertaking.

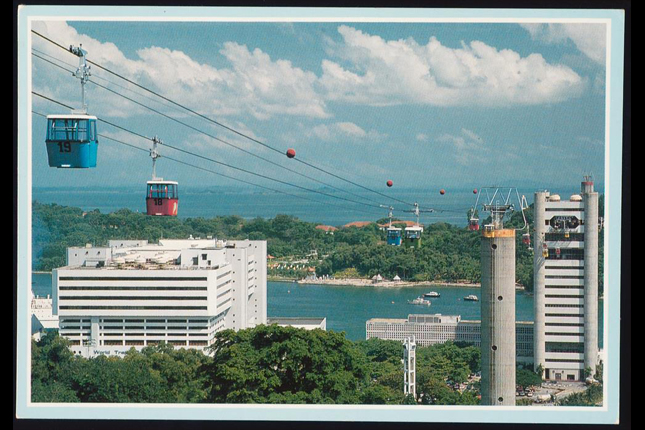

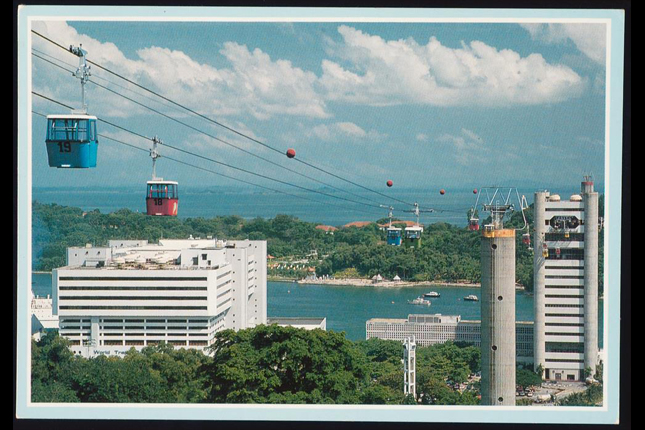

To connect visitors from mainland Singapore (via Mount Faber) to Sentosa, a cable car system was rolled out in 1974. It was well-received, with 50,000 passengers taking it monthly for almost a year. To cope with demand, more cars were added.

In its early years, visitors could only access Sentosa by ferry or cable car. This changed when a monorail was completed in 1982. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

In its early years, visitors could only access Sentosa by ferry or cable car. This changed when a monorail was completed in 1982. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Soon after, attractions such as the Sentosa Golf Club, Sentosa Coralarium, the Palawan Beach Lagoon, a musical fountain, and Fort Siloso which was repurposed into an educational pitstop, were completed. Later, a butterfly park, and the Surrender Chambers which housed waxwork exhibits detailing Singapore’s WWII story, opened to the public.

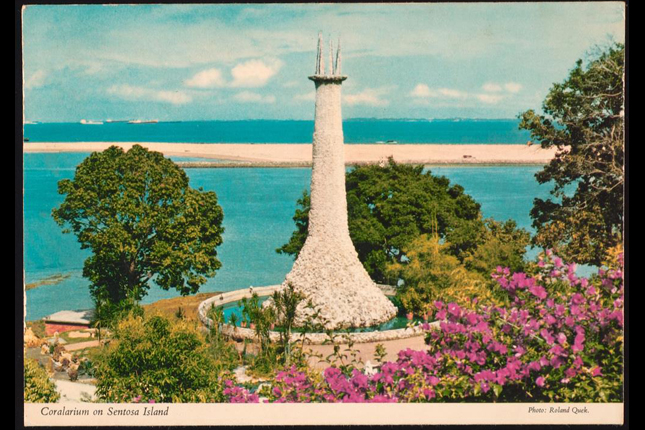

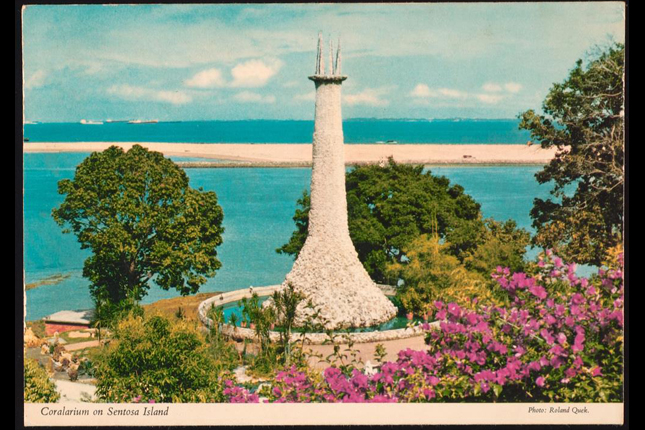

An 18-metre-tall coral tower perched atop Mount Serapong. It was part of the Coralarium complex in Sentosa. It has since been dismantled. (Mid-1970s. Image from the National Museum of Singapore).

An 18-metre-tall coral tower perched atop Mount Serapong. It was part of the Coralarium complex in Sentosa. It has since been dismantled. (Mid-1970s. Image from the National Museum of Singapore).

Sentosa’s Musical Fountain. (Mid-1980s. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Sentosa’s Musical Fountain. (Mid-1980s. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Visitorship hit a million during the financial year of 1979/1980.

Not all was smooth sailing. In 1983, a drillship crashed into the Sentosa cableway, knocking off two cars which plunged 55 metres into the sea. Seven passengers died.20

After the incident, the Sentosa Development Corporation put in place measures to better ensure visitor safety.21

In the evening of Jan 29 1983, the steel lattice tower of oil drillship Eniwetok crashed into the Sentosa cableway. (The Captain R. F. Short Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore)

In the evening of Jan 29 1983, the steel lattice tower of oil drillship Eniwetok crashed into the Sentosa cableway. (The Captain R. F. Short Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore)

Keeping it fresh

Over the years, the Sentosa Development Corporation has had to refresh its offerings to satiate changing appetites and generate ongoing interest.

Infrastructural improvements, facelifts to existing destinations, as well as the addition of new hotels and attractions such as Underwater World Singapore, and an $8 million, 12-storey high sculpture of the Merlion marked the 1990s.

In the 2000s, the island began hosting popular beach dance parties. Sentosa Cove, a residential enclave for the ultra wealthy, was launched in 2003.

In 2010, Resorts World Sentosa comprising the Universal Studios theme park, as well as the Republic’s first casino, opened its doors.

As of 2022 — Sentosa’s 50th anniversary — plans are afoot to update and expand the paradise island yet again.22

The man-made island paradise is refreshed regularly to cater to ever-evolving visitor appetites. (The Lee Leng Kiong Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.)

The man-made island paradise is refreshed regularly to cater to ever-evolving visitor appetites. (The Lee Leng Kiong Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.)