Text by Kan Shuyi

Images courtesy of Shaanxi Cultural Heritage Promotion Center and Famen Temple Museum

Be Muse Volume 7 Issue 2 – Apr to Jun 2014

The Discovery

Shining their torches into the dark depths, the archaeologists were astonished to see gleaming articles of gold and silver packed into a stone chamber. It was April 3, 1987, and this was their first sight of the crypt beneath the Famen Temple pagoda, which had been built in the early 17th century. Structurally weakened by earthquake tremors and age, the pagoda had collapsed after a period of heavy rainfall on August 24, 1981. Local authorities had decided to rebuild the pagoda after its dramatic fall, leading to a full-scale excavation of the site – and one of China’s major archaeological discoveries of the twentieth century.

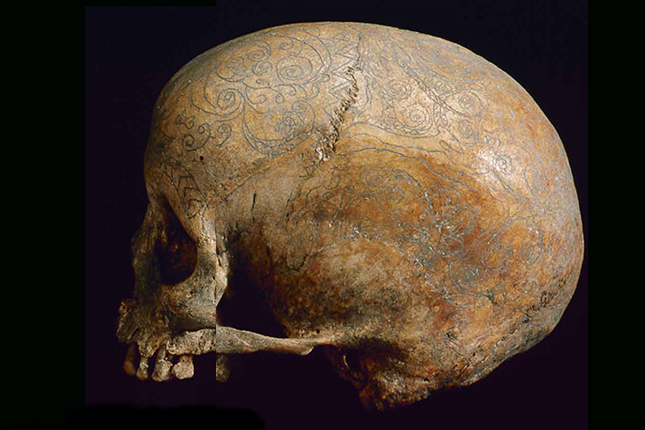

Not one, but three chambers containing a rich variety of items were discovered in the underground complex. The subterranean structure, which included a flight of stairs and a corridor leading to the three successive rooms, measured 21.1 metres in its entire length and 2 to 2.55 metres in width. This was the large Tang pagoda crypt found to date and contained hundreds of objects, which included gold and silver utensils, precious ceramics, rare Islamic glassware, silk textiles, and one carvings. But most significant among the finds was the finger bone relic of the Buddha. In fact four finger bone relics were recovered, one in each of the three chambers and the fourth in a tiny squarish compartment hidden beneath the rear chamber.

This fourth relic is purported to be the genuine one, referred to in Chinese sources as the zhen shen (“true body” relic) and the ling gu (灵骨, “spirit bone”), while the other three relics found in the three main chambers are described as ying gu (影骨, “shadow bone”). Two of these ying gu were made of jade and the third of bone, and they may have served as decoys to protect the true relic during religious persecutions in the mid-ninth century.

The Famen Temple was one of four Buddhist sites in China reputed to house the fingerbone relic of the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni. The other three were Puguangwangsi in Sizhou, Jiangsu province; Mount Wutai in Daizhou, Shanxi province; and Wutai in Mount Zhongnan, Shaanxi province. Traces of the relics at these other locations have, however, lost over time.1

The Famen Temple

Famensi (法门寺), also known as Famen Temple or Famen Monastery, is situated approximately 110 km west of Xi’an in Fufeng county, Shaanxi province. Its beginnings remain obscure but its history with the Buddha’s relics is legendary. The Famen Temple was believed to be founded in the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220), when it was known as Ayuwangsi (阿育王寺 or Aśoka Temple). The relic at the site was also associated with King Aśoka (reigned 269–232 BC) of the Mauryan dynasty, who according to Buddhist tradition re-collected Buddha’s relics and re-dispersed them to 84,000 stupas. What has been determined with greater certainty, however, is that the finger bone relic was worshipped in 555. This was the first time the veneration of the Buddhist relic at the Famensi site was recorded in writing.

This textual evidence came from one of two one steles found within the crypt. Inscribed in 874, this one stele provides a broad overview of the history of Famen Temple. It outlines the various occasions on which the relic was worshipped, and describes in particular detail the final occasion when the relic was conveyed to the capital city in 873. During the Tang dynasty, the relic was first worshipped in 631 upon the orders of Emperor Taizong (reigned 626–649). Other Tang rulers continued with the practice and the crypt was accessed in 660, 704, 760, 790, 819, and 873. Venerating the relic was believed to invoke good fortune and protective blessings for oneself and the empire.

On each of these occasions, the relic was conveyed to the imperial palaces at Chang’an (and sometimes Luoyang, the secondary capital of Tang China) amid much ceremonial splendour. It incited great religious fervour among the devout masses, and extreme acts of piety such as self-immolation were also noted. New offerings were likely to have been made each time the relic was re-interred at the Famen Temple, but most of these items did not survive the suppression of Buddhism in the mid-ninth century. Thus the majority of objects from the Famen Temple crypt are dated after this period and associated with the Emperors Yizong (859–873) and Xizong (873–888), the last two Tang emperors who participated in the veneration of the relic.

The Secret Treasures

340 items and sets of items were excavated from the Famen Temple crypt, a figure which excludes the thousands of coins found.2 It also does not reflect the full quantity of textiles that had been originally placed in the crypt, as conservation work on this aspect is ill ongoing. Not only is this an impressive quantity of objects recovered from a single site, the quality of these items is exquisite. Many objects are unprecedented in form and/or decoration, including several rare works featuring Esoteric Buddhist iconography, such as the reliquary casket decorated with forty-five Buddhist figures. This is the earliest known visual representation of the Diamond Realm mandala in China, one of two major realms in Esoteric Buddhism.3

Famen Temple Museum.

The objects – serving both religious and secular functions – were mostly presented by members of the Tang royal household for the veneration of the Buddhist relic. They had access to some of the finest objects manufactured and, as inscriptions on several of the excavated metal wares indicate, these included products from the imperial workshops in Chang’an as well as tributes from key metal-smithing centres in the southern part of China. The boldly-ornamented, tiered incense burner and the sumptuously decorated basin represent these production areas respectively. They are also two of the large surviving examples of Tang metalwork known at present.

Famen Temple Museum.

Famen Temple Museum.

The discovery also yielded one of the most comprehensive sets of utensils used for the preparation and drinking of tea, highlighting the popularity of the beverage in ninth-century China. Noted for its many benefits, tea was enjoyed across Tang society. The royal court was no exception and tea appears to have been particularly loved by Emperor Xizong. Several of the Famen Temple tea utensils are inscribed with the characters “五哥” (wu ge or fifth brother), a reference to the monarch’s infant name, which suggests that the objects were used specifically by him.

Famen Temple Museum.

Famen Temple Museum.

Enhancing the significance of the find is the fact that the majority of these objects were recorded in the second stone stele found in the crypt. This was essentially an inventory checklist that listed the names, quantity, and weight of objects, as well as the donors who had given them to the Famen Temple. The information gleaned from this list has enabled archaeologists and scholars to gain important insights into Tang China, such as the system of measurements that was used then. This is currently the only inventory stele that has been excavated from an archaeological site in China, making it a unique and invaluable piece of epigraphical evidence.

The inscribed information on the inventory stele has also been key to the identification of mi se (秘色) or “secret colour” porcelain. “Secret colour” ceramics were widely celebrated in poetry during the Tang and succeeding dynasties, when their lustrous appearance was compared to the “emerald green of a thousand peaks” and “fresh lotus leaves covered with dew”. However, the actual colour of these ceramics remained a mystery until the discovery of the Famen Temple crypt and its contents, when thirteen excavated celadon vessels were matched with the inscriptions on the stele. These precious ceramics with a bluish-green hue had been produced at the Yue kilns in northern Zhejiang province, where they were made with the finest materials and under strict firing conditions.

Famen Temple Museum.

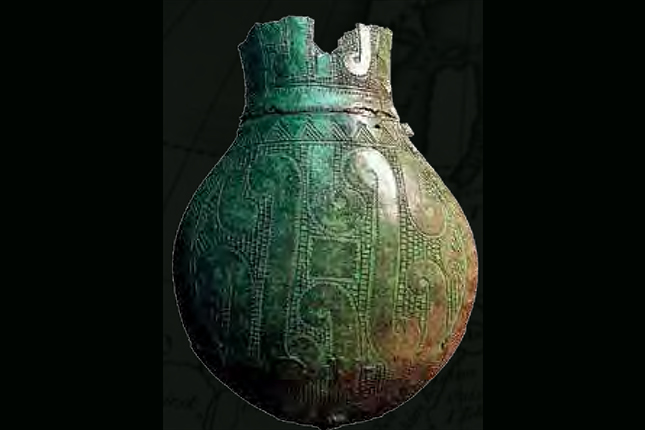

Another group of rare finds from the Famen Temple crypt are eighteen pieces of glassware imported from the Middle East. Of various forms and designs, this cache of treasures constitutes the largest group of early Islamic glass vessels (found in mostly intact conditions) currently known in China. Deemed an exotic luxury in Tang China, Islamic glass was valued for its beauty, strength, and transparency. Its preciousness made it suitable for making containers for housing relics, such as the bottle placed in the rear chamber of the crypt. The bottle was found with a fragmentary slip of paper inked with two lines of characters, of which only two— “true” (真) and “lotus” (莲)—remain legible. This suggests that the vessel may have contained a relic of the Buddha; the lotus is a Buddhist symbol, and the finger bone relic is referred to as the True Body on the inventory stele.

Famen Temple Museum.

Indeed, we can only speculate about many aspects of the Famen Temple and its contents. While it has been an invaluable time capsule that has enriched our knowledge of Tang society, much remains enigmatic, awaiting further resolution by current and future scholars.

Kan Shuyi is Curator, Asian Civilisations Museum

Discoveries from the Famen Temple was exhibited at the Asian Civilisations Museum (ACM) in early 2014. The exhibition – The Secrets of the Fallen Pagoda: Treasures from Famen Temple and the Tang Court – is organized by the ACM in partnership with the Shaanxi Provincial Cultural Relics Bureau and the Shaanxi Cultural Heritage Promotion Center, People’s Republic of China.

Notes