Text by John Kwok

MuseSG Volume 9 Issue 2 – Apr to Jun 2016

Every morning, 64-year-old (at the time of writing) Mr Quek Kim Kiang checks the tools of his trade, a pair of hooked poles, before he heads out to the mangroves. There he wades into knee-deep waters to catch mud crabs by hooking them out of their mud holes. He is careful to make sure that the crabs are not injured or broken in the process. If the crab caught is a juvenile, it goes back to the mangroves.

Ahmad Kassim, 80 years old at the time of writing, lives away from the mangroves. His home is a large wooden house that his father built during World War II. He has added a shop to his home and sells drinks to visitors. Recalling life in the village, he says, “In the past, we villagers practised gotong royong. We worked together. Neighbours came together to help each other.” Ahmad does not speak English but he understands the language of a thirsty person. The drinks he sells are not overpriced.

These men are part of a small community of residents who live on Pulau Ubin, Singapore’s kampong (“village” in Malay) island off the northeast coast of Singapore.

The story of Pulau Ubin is intimately tied to Singapore in the way of a metropolis and its frontier. The British claimed Pulau Ubin (then spelled Pulo Obin) on August 4, 1825 when John Crawfurd led an expedition to the island from Singapore, which the British had colonised only six years earlier. Crawfurd hoisted the Union Jack on the island and with a 21-gun salute, claimed Pulau Ubin and the small community of woodcutters there as part of the British Empire. Pulau Ubin was later described as an important island that commanded the entrance of the “highway for all vessels trading to China and the Far East”.

In an effort to combat piracy on the Johor Straits in the early 1850s, the colonial administration encouraged Malay settlers to colonise the island with tax-free land incentives to prevent pirates from using the island as a hideout. Another wave of Malay settlers came in the 1880s from the Kallang River in Singapore to settle around the coastal kampongs such as Noordin, Mamam and Petai. These settlers became fishermen.

By 1847, Pulau Ubin was settled by the Chinese who started private quarrying companies on the island to quarry granite and feed the demand for stone as the colony of Singapore expanded. Later in the 1850s, the colonial administration established large-scale granite quarrying operations on Pulau Ubin for the construction of the Horsburgh Lighthouse on Pedra Branca, the Raffes Lighthouse, the Causeway, Pearl’s Hill Reservoir, Fort Canning and its reservoir, and the Singapore Harbour.

At the turn of the 20th century, large tracts of land on the island were cleared for cash crop cultivation. Coffee, nutmeg, pineapple, coconut, tobacco and rubber plantations were opened up on the island but only rubber remained profitable. Together with granite quarrying, these became the pillars of the island’s economy. Not all the people in Ubin were involved in granite quarrying or rubber cultivation. Coffee shops and provision shops were opened across the island to cater to the needs of the quarry and plantation workers. Boat operators started ferry services to connect parts of the island together as the mangrove swamps were impassable on foot. This was an important service as the Tua Peh Kong temple, the focus of religious life on Pulau Ubin, was located at the main town on the island. It was only after the introduction of prawn farms to Pulau Ubin in the 1950s that many of the swamps were drained, linking up the different parts of Ubin and making most of the island accessible by foot.

Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The 1950s also marked important milestones in Pulau Ubin’s history. The first educational institution, Bin Kiang School, was established in 1952 to provide education to the island’s children, and a maternity and child health clinic was set up in 1957. Both reflected the increasing needs of the island’s growing community.

Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Population growth on Pulau Ubin reflected the island’s economic development. In the 1970s, Pulau Ubin had a population of 2,000 to 4,000 people as granite quarrying reached its peak, due largely to the formation of the Housing & Development Board in 1960 that started large-scale housing development projects across Singapore. By the 1980s, granite quarrying operations were starting to fold up due to the drop in demand for local granite. Rubber cultivation on Pulau Ubin also declined in the 1980s as the soil was exhausted and plantations were no longer profitable to run. The loss of these economic pillars saw many people leaving the island. The population fell to 1,000 people in the late 1980s and by the mid-1990s, the population of Pulau Ubin was approximately 400. By 2001, the population fell to below 200 and it has remained that way ever since.

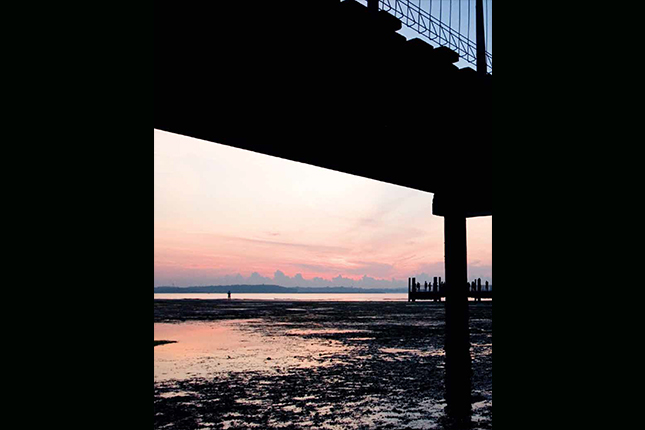

Pulau Ubin’s population decline and loss of economic significance should not be taken as a sign of failure. The island continues to play an important role at Singapore’s frontier. The former quarry sites have been reclaimed by nature and transformed into large lakes. The jungle and mangroves have grown into the abandoned plantations creating secondary forests and enabling wildlife to return to the island. The island is now colonised by species of bats, herons, hornbills and crabs that are no longer found in Singapore.

Courtesy of John Kwok.

Thousands of people travel to Pulau Ubin every year, not as workers or commuting residents, but visitors who wish to experience the island’s natural and cultural heritage. They come to experience the rustic way of life – the kampong life – that can no longer be found anywhere in the metropolis. For example, the annual Tua Peh Kong festival celebrated on the island is a six-day festival featuring processions, opera performances, lion dances, mediumship and getai (live stage performances more popularly associated with the Hungry Ghost Festival). Such a long duration of celebrations is no longer practiced in Singapore. While vestiges of Pulau Ubin’s tangible past − the former maternity and child health clinic, the Tua Peh Kong temple, abandoned fish farms and quarries, and kampong houses reminds us of Ubin’s history, the stories of local residents like Mr Quek and Mr Ahmad continue the story of Pulau Ubin as the living kampong on Singapore’s frontier.

Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Courtesy of John Kwok.

Mr Quek Kim Kiang settled in Pulau Ubin sometime in the late 1980s when the population on the island was in decline. Unlike other residents on Pulau Ubin, Mr Quek alternates between living in a house on the island and on a fishing platform anchored just off the southern coast. The fishing platform is a reminder of his past as a fisherman. These days he catches more crabs than fishes. He uses traps and hooked metal poles to catch freshwater mud crabs on the island’s mangrove swamps.

Courtesy of John Kwok.

Mr Quek is keenly aware of the impact of human activities on Ubin’s ecosystem. He recalled an incident when he encountered someone who caught a small-sized crab and he confronted him. The person responded: “If I don’t catch it, someone else will.” Mr Quek continues to catch crabs in a sustainable manner, releasing juvenile crabs that he catches that are too small back to the wild. He has also taken on a ten-year-old apprentice who is eager to learn the skills of a fisherman.

Courtesy of John Kwok.

Mr Ahmad Kassim and his wife reside permanently on Pulau Ubin as of 2016. He arrived on the island with his father and his six siblings during the Japanese Occupation of Singapore. He remembered that life during the war period was difficult and their diet consisted mainly of tapioca. That was until the Japanese offered him and his family some work and they were paid in rice. However, as Ahmad recalled: “When we got the rice, we sold it to the Chinese. We took the money and went gambling.”

Courtesy of John Kwok.

When the war ended, Ahmad remembered the Communists taking over from the Japanese on the island. They came with machine guns, pistols and bayonets. However, after a week, the British returned to the island and chased the Communists out.

Ahmad also remembers a time when his fellow villagers used to call him Ahmad Janggut: Ahmad the Bearded. As of 2016, his family and his brother’s family are the only ones left in Kampong Melayu.

NHB’s year-long Pulau Ubin Cultural Mapping Project, concluded in April 2016, included a 25-minute documentary titled "Life on Ubin". The documentary presents the memories and experiences of current and former residents of Pulau Ubin.