MUSE SG Volume 15 Issue 02 - July 2022

Text by Dr Johannes Widodo, Associate Professor, National University of

Singapore

Read the full

MUSESG Vol. 15 Issue 2

The city is a collective memory, a result of the contributions of all of its

inhabitants accumulated over time.1 Place names, tangible features

such as natural elements and architecture, and intangible aspects like

history, events and communities—all of these form one’s sense of

place. On another, more personal level, we as the city’s inhabitants

ascribe meaning to a place with our memories of it. As such, decisions to keep or change a place, or even erase it,

bear

significant consequences—affecting one’s sense of place and

attachment to the locale.

Place Heritage: Beyond the Tangible

Two elderly men playing Chinese chess in a hawker centre. Place heritage

comprises not just the built environment, but also communities that have

formed organically over time in a particular locale. Image courtesy of Heng

Lim/Shutterstock.com

Two elderly men playing Chinese chess in a hawker centre. Place heritage

comprises not just the built environment, but also communities that have

formed organically over time in a particular locale. Image courtesy of Heng

Lim/Shutterstock.com

Place heritage traditionally referred to buildings and sites, while heritage

properties were mainly associated with monuments and buildings, without any

relationship to their surrounding landscape.2 Today, the meaning of

place heritage has been expanded to include the interaction between tangible

and intangible aspects rooted in the cultural landscape, referring to a

symbiosis of human activity and the environment.

Place heritage conservation therefore protects and upholds a set of values

that the community has maintained for decades—historical, architectural,

social, cultural, timelessness, economic and contextual.3 Part of it is retaining the

‘authenticity’ of a place, which helps people understand

themselves and their place in society as a whole. In the process of place

conservation, people collectively figure out what identity is, what a sense of

belonging means, and recognise them. The authenticity of a locale’s heritage is thus one of the most crucial

factors in considering how everyone, including residents and visitors, can

develop a genuine appreciation and attachment to a place from the past through to the present for the benefit of future

generations.

Shophouses along East Coast Road. The iconic red-brick building used to

house Katong Bakery and Confectionery, or ‘Red House Bakery’, a

popular breakfast spot for residents in the area. Established in 1925, Red

House Bakery closed in 2003. Today, the refurbished shophouse is home to

micro red | house, a modern bakery serving up sourdough loaves.

Shophouses along East Coast Road. The iconic red-brick building used to

house Katong Bakery and Confectionery, or ‘Red House Bakery’, a

popular breakfast spot for residents in the area. Established in 1925, Red

House Bakery closed in 2003. Today, the refurbished shophouse is home to

micro red | house, a modern bakery serving up sourdough loaves.

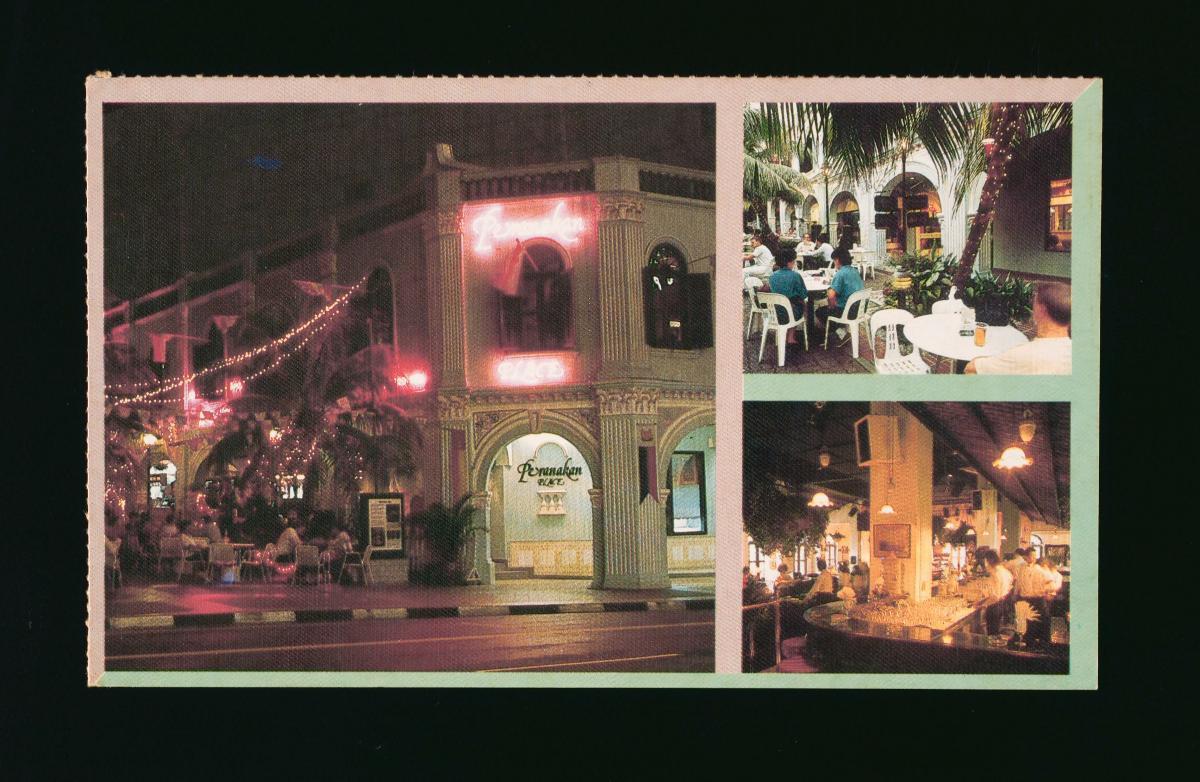

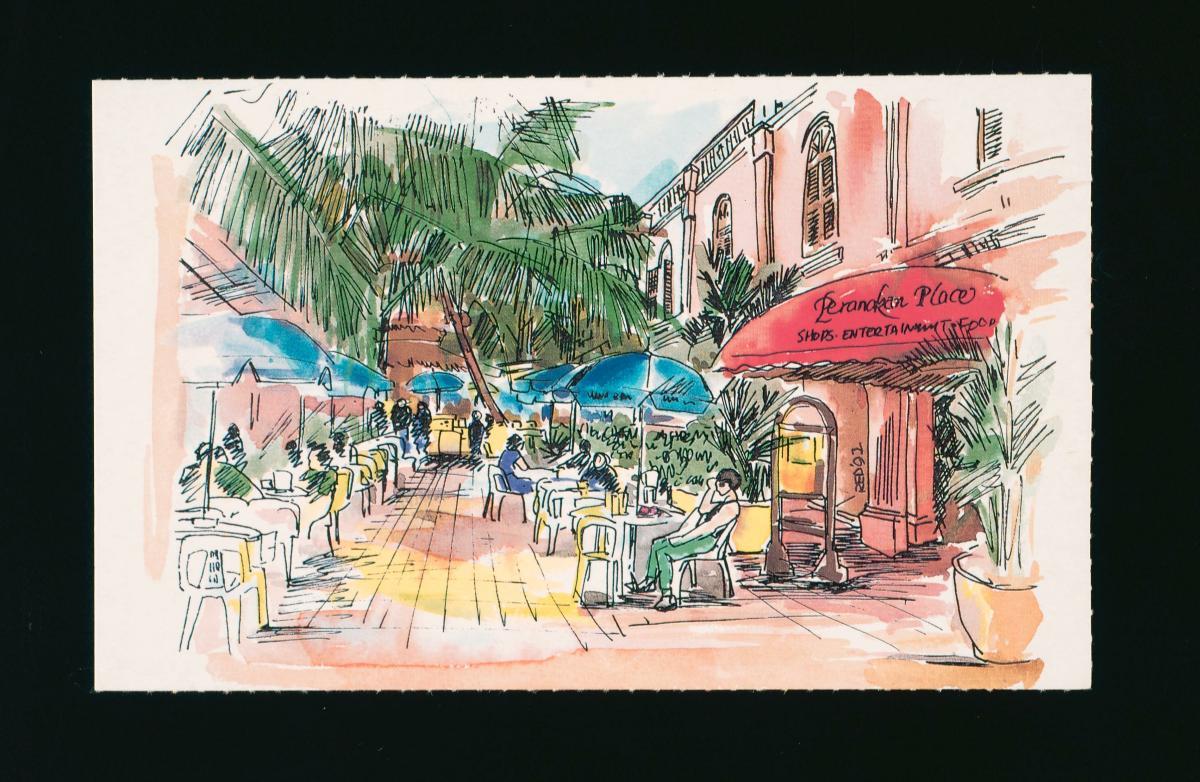

Safeguarding Singapore’s Place Heritage

The priority of Singapore from its independence in 1965 to 1989 was economic

development and housing. In those decades, the city-centre was radically

transformed from a slum and squatter zone into a modern financial and business

hub. However, understanding the importance of place heritage amid the need for

development, the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) launched its Conservation

Plan in 1989, which focused on physical conservation and city rebranding

efforts.4 Conservation policies and guidelines at the time were

inclined towards the conservation of the country’s multi-ethnic and

colonial built heritage.

Boat Quay, c. 1930. Quays are manmade platforms built alongside or into

water to allow ships to dock and unload cargo. Image courtesy of National

Archives of Singapore

Boat Quay, c. 1930. Quays are manmade platforms built alongside or into

water to allow ships to dock and unload cargo. Image courtesy of National

Archives of Singapore

Present-day Boat Quay. Although the original functions of the harbour and

its associated activities have changed, the place name that carries the

memory of the past is still in use today. Image courtesy of author

Present-day Boat Quay. Although the original functions of the harbour and

its associated activities have changed, the place name that carries the

memory of the past is still in use today. Image courtesy of author

Under the Conservation Plan, conservation status was granted to historic

districts like Chinatown, Little India, Kampong Gelam and areas surrounding

the Singapore River. Later, secondary settlements such as Joo Chiat and

Geylang were also granted conservation status. While the conservation policy

was geared towards protecting built heritage to preserve a distinctly

‘local’ flavour that would resonate with the people, a component

of it was to drive tourism numbers.

URA adopted a stylistic classification for shophouse architecture for various

conservation areas such as Chinatown, Kampong Gelam and Little India.5 This classification is defined

according to linear periodisation, with

meticulous stylistic descriptions of the architectural features: Early

Shophouse Style (1840–1900), First Transitional Shophouse Style (early

1900s), Late Shophouse Style (1900–40), Second Transitional Shophouse

Style (late 1930s) and Art Deco Shophouse Style (1930–60).

According to URA’s conservation guidelines, the facades of shophouses

are to be retained as a priority, with some flexibility in the

building’s interior to support adaptive reuse. Conserving the facades of

old shophouses helped create a visual identity for these places, which were in

turn also rebranded accordingly as ‘Little India’ and

‘Chinatown’ to impress upon tourists the identity of these

historic areas.

The former Singapore Improvement Trust flats built in the 1930s for customs

workers in the Chinatown area have been repurposed for commercial

activities, 2004. Image courtesy of author

The former Singapore Improvement Trust flats built in the 1930s for customs

workers in the Chinatown area have been repurposed for commercial

activities, 2004. Image courtesy of author

Alongside the conservation work of URA was the former Preservation of

Monuments Board, known today as the Preservation of Sites and Monuments (PSM),

under the National Heritage Board. URA’s mandate is to carry out

conservation albeit allowing modifications to accommodate development, while

PSM is the national preservation authority whose mandate is to identify

structures and places of national significance and gazette these for

preservation as national monuments. One of its functions is to ensure the full

authenticity of the preserved buildings and sites.6

Due to the focus on the conservation and preservation of built heritage from

the late 1980s to the early 2000s, little attention was paid to preserving

existing communities, their ways of life or the sociocultural fabric. Thus,

much intangible heritage was lost in those decades due to gentifrication as

old businesses were driven out by market forces and communities relocated due

to development. But this was to change in the new millennium, when a more

holistic manner of conservation became the overarching framework.

The Urban Redevelopment Authority’s stylistic classification for

shophouse architecture in the conservation area of Little India:

Early Shophouse Style (60 Buffalo Street)

First Transitional Shophouse Style (39 Campbell Lane)

Late Shophouse Style (47 Desker Road)

Art Deco Shophouse Style (35 Cuff Road)

Holistic Conservation

Changes in the political climate and public aspirations saw the government

gradually shift from a top-down approach to a more participatory strategy for

urban conservation in the early 2000s. This was partly to nurture

Singaporeans’ sense of ownership and stewardship of the city’s

architectural and place legacy. The public desired a more inclusive framework

for conservation, where a balance could be struck between conservation and

redevelopment. Government policy increasingly moved towards holistic

conservation—an integrated, synergistic approach beyond physical

structures to include communities and activities that contribute to a locale.

From August 2000 to May 2001, URA held public consultations in the urban

planning process for the Concept Plan 2001.7 Ideas and

contributions from the public were gathered through public forums, exhibitions

and dialogues before the Concept Plan was finalised at the end of 2001. A

similar process was implemented in the following year when the Master Plan

2003 was being drafted. Specifically, the Ministry of National Development

appointed three subject groups comprising professionals, representatives from

interest organisations and laypeople to study proposals relating to: (1) Parks

and Waterbodies Plans and Rustic Coast, (2) Urban Villages and Southern Ridges

and Hillside Villages, and (3) Old World Charm. The ideas and recommendations

were incorporated in the draft of the Master Plan 2003.

A Buddhist-Taoist makeshift shrine, popularly known as Ci Ern Ge, under an

old banyan tree in Toa Payoh Central, 2005. The tree and the shrine were

interwoven into the new urban fabric when the town centre was built around

1966–70. Image courtesy of author

A Buddhist-Taoist makeshift shrine, popularly known as Ci Ern Ge, under an

old banyan tree in Toa Payoh Central, 2005. The tree and the shrine were

interwoven into the new urban fabric when the town centre was built around

1966–70. Image courtesy of author

The restored Buddhist-Taoist shrine (photographed in 2022) in Toa Payoh

after the tree collapsed due to a storm in 2013. The restoration was

supported by the Singapore Toa Payoh Central Merchants’ Association,

against the initial plan to clear the shrine by the National Parks Board.

Image courtesy of author

The restored Buddhist-Taoist shrine (photographed in 2022) in Toa Payoh

after the tree collapsed due to a storm in 2013. The restoration was

supported by the Singapore Toa Payoh Central Merchants’ Association,

against the initial plan to clear the shrine by the National Parks Board.

Image courtesy of author

No longer were policymakers focused solely on built heritage; communities,

trades, traditions and activities could all contribute to the ‘old-world

charm’ of a place. Such a holistic conservation approach thus includes

modern and less aesthetically significant structures. The framework is

multidimensional, encompassing buildings, traffic patterns, streetscapes, open

spaces, and views. Holistic conservation therefore necessitates

multidisciplinary participation at both local and national levels, and it

involves all conservation stakeholders—users, owners, heritage

supporters and decision-makers.

Voices from the Ground: Heritage and Nature Advocacy

An impetus for the above-mentioned policy changes can be attributed to the

active engagement with government bodies by heritage societies. The Singapore

Heritage Society was established in 1986 as a non-profit organisation

dedicated to preserving, transmitting and promoting Singapore’s history,

legacy and identity.8 The society advocated for the future use of

the former KTMB (Keretapi Tanah Melayu Berhad) Rail Corridor and the Bukit

Brown Cemetery, working together with the Nature Society (Singapore).

The Nature Society (Singapore) has a history that stretches back to 1921, and

it is presently a nongovernmental organisation that promotes nature

appreciation, the conservation of natural resources, and engagement in local,

regional and global initiatives to preserve biodiversity.9 Its

advocacy work has seen success in the now-conserved Sungei Buloh Wetlands

Reserve and Chek Jawa in Pulau Ubin. In 2015, the Nature Society and the

Singapore Heritage Society collaborated on

Green Rail Corridor: A Guide to the Ecology and Heritage of the Former

Railway Land—a comprehensive map of the former rail corridor that explores its

diverse ecology and cultural heritage.

Visitors walking along the Rail Corridor before the removal of the rail,

2011. Image courtesy of author

Visitors walking along the Rail Corridor before the removal of the rail,

2011. Image courtesy of author

Heritage advocates based online, particularly on social media, have also

mushroomed organically within the last decade in Singapore. Today, we have

social media groups and other online communities made up of individuals with a

shared interest in place heritage: Facebook groups Tiong Bahru Heritage

Trails10 and Heritage Singapore – Bukit Brown Cemetery;11

blogs ‘Bukit Brown: Living Museum of History and Heritage’12

and ‘All Things Bukit Brown: Heritage, Habitat, History’;13

websites The Green Corridor,14 Wild Singapore15 and

Singapura Stories;16 and many more.

In 2014, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) Singapore

was founded as a non-governmental organisation consisting of professional

heritage practitioners who have worked closely on public and private projects

pertaining to Singapore’s heritage sites. ICOMOS is an advisory body to

UNESCO which actively contributes to the implementation of the World Heritage

Convention.

A more recent addition to the ground-up heritage landscape is the non-profit

group Documentation and Conservation of Buildings, Sites and Neighbourhoods of

Modern Movement, or Docomomo Singapore, established in 2021.18 Docomomo Singapore aims to create

awareness among Singaporeans on the

nation’s modern built heritage. Besides research and advocacy work, it

also works with partners to find creative, sustainable and inclusive ways to

conserve and retrofit the modern built heritage of Singapore.

Social media’s influence on the increasing interest in heritage and

sense of belonging among the younger generation cannot be underestimated. It

will continue to be an essential platform of engagement that can change

people’s perception of and their attachment to heritage places. Needless

to say, the proliferation of heritage groups online and offline has greatly

increased community involvement in heritage-related issues, contributing to a

stronger shared ownership of Singapore’s place heritage.

A Shared Responsibility

Although the National Heritage Board is the official custodian of

Singapore’s heritage, non- governmental organisations and other

community movements are crucial in the stewardship of Singapore’s

heritage. It is the responsibility of everyone to preserve and celebrate the

shared heritage of our diverse communities, as the integrity of the tangible

and intangible heritage entrusted to us by past generations depends on us.

A resident of Pulau Ubin sharing stories about the community and place to a

group of visitors, 2019. Image courtesy of author

A resident of Pulau Ubin sharing stories about the community and place to a

group of visitors, 2019. Image courtesy of author

Under our generation’s stewardship, it may be destroyed, damaged,

altered or abused; on the other hand, it may also be restored, repaired,

maintained, conserved or preserved. Conserving our natural and cultural

legacies is an act of managing changes, extending the past to the present and

the future for the current and subsequent generations—and this requires

the active involvement of everyone, not only the government.

The importance of the retention of identities through the preservation and

conservation of natural and cultural heritage—especially place

heritage—will become even more crucial as the development and

redevelopment of our urban areas continually expand outwards to cater to the

needs of a larger population and economic growth. But we must never forget

that we need to preserve the people’s memories, identities and sense of

place for future generations. Heritage conservation is, after all, about the

people.