Text by Peter Lee

BeMuse Volume 4 Issue 2 - Apr to Jun 2012

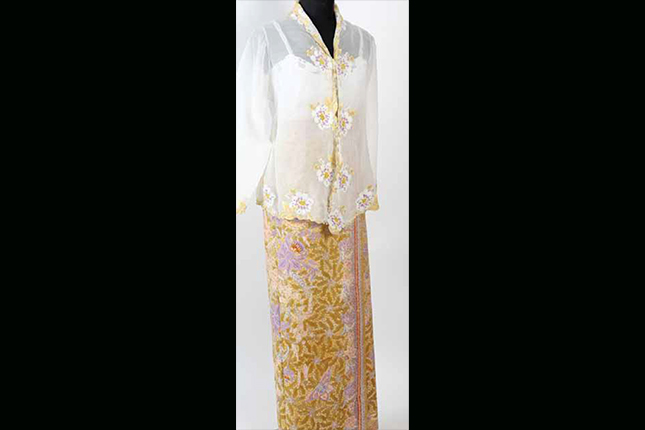

Now more than ever, the image of a woman in a sarong kebaya resonates with the Singaporean public – from the iconic Singapore Girl to the Little Nyonya of primetime TV and even to the blown-up images of Ivan Heng as the sultry Emily Gan in Emily of Emerald Hill. The sarong kebaya, a tubular batik skirt worn with a fitted blouse, is still proudly worn by Peranakan women – Nyonyas – in Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and Myanmar. The diverse influences that led to this enduring garment are traced in a new exhibition at the Peranakan Museum.

The early 20th century was the golden age of the Peranakan sarong kebaya, and in recent years the garment has experienced a major revival. Yet perhaps at no other moment has the sarong kebaya been so misunderstood.

One of the most arresting images of Mediacorp’s hit television series Little Nyonya, set between the 1930s and the 1950s, was of the protagonist cooking up a feast in the kitchen. Simply but immaculately dressed in a sarong kebaya, she wore her hair neatly pulled up into a chignon. However, during that period, unmarried girls did not wear an expensive and delicate sarong kebaya into the kitchen, and chignons were only sported by their mothers and grandmothers, while they themselves preferred modern short crops, crimps and perms. And most of the batik sarongs shown in the series are of a type popular only in the late 1950s and 1960s. Such anachronisms are common – and have arisen because of the dearth of information on Peranakan fashion. An exhibition at the Peranakan Museum from 1 April 2011 to 26 February 2012 aimed to fill in the gaps.

Sarong Kebaya: Peranakan Fashion and its International Sources presented the historical and stylistic phases of the Peranakan sarong kebaya from the 1800s to 1950s. It revealed fascinating aspects about the origins of both components of the costume over five centuries. On display were 131 objects, including 58 outfits presented in chronological sequence. Many of the cloths and kebayas belonged to types that have never been published before, including rare treasures from the Peranakan Museum, from the collection of Mr and Mrs Lee Kip Lee, and from three Dutch museums: the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague, the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam and the Museum Volkenkunde in Leiden.

Distant Origins

The exhibition began with rare textiles from the 16th to 19th centuries that reveal the history of skirt cloths and sarongs. Some of these ancient patterns can still be found on batiks worn today. The ports of maritime Asia had long been dynamic centres of exchanges between cultures. One medium of cultural contact was cloth. By the 16th century, Indian textiles from Gujarat and the Coromandel Coast were extremely popular commodities used by Arab, Indian and European traders to barter for spices from the Malay archipelago. Although sarong is a term used nowadays to describe any kind of wrapped skirt, it is in fact a long cloth sewn into a tube (sarung means ‘sheath’ in Malay). Early examples of wrapped skirts and ceremonial cloths, as well as the earliest documented sarong made from an Indian textile, were among the treasures on display.

Sarong – Java, Pekalongan, ca. 1880-1920. Signed: Lien Metzelaar. Cotton (hand-drawn batik). Colletion of Mr & Mrs Lee Kip Lee.

Two key types of garments were introduced. The prototypical kebaya is a long loose jacket derived from the ancient qaba, an Islamic robe worn at least since the 9th century by rulers across the Middle East, Central Asia and northern India. By the 17th century it had become a common garment worn by both men and women of the elite classes across the region. Even the Brahmins of Calicut (now Kozhikode in Kerala, India) wore a long white gown called a cabaye, ‘of very white cotton, reaching to the heels’.1 Variant spellings include cabaia, kabaai and kabay. However, in the 19th century, this robe was called a baju panjang (‘long robe’ in Malay) in Malacca, and was worn by Peranakan women until the early 20th century. The other key robes was the baju, a hip- or knee-length tunic with a V-shaped opening for the head. This is derived from the bazu, another ancient Islamic garment. In the 17th century it was common all over the Indian Ocean and the Malay archipelago, and worn by men and women, including the women of the first Eurasian communities in the Portuguese colonies of Goa and Malacca, and even in the Spice Islands further east. European travellers noticed that women wore a baju “so fine that you may see all their body through it”.2 Another traveller noted that the baju worn by noblewomen in the court of Banten in Java were “so lightly executed that their embroidery does not hinder one from perceiving their naked bodies.”3 This tropical engagement with see-through fabric endured till the 20th century.

Sarong – Java, Lasem, late 19th to early 20th century. Cotton (hand-drawn batik). Collection of Mr and Mrs Lee Kip Lee.

Early Nyonya ‘Bajus’

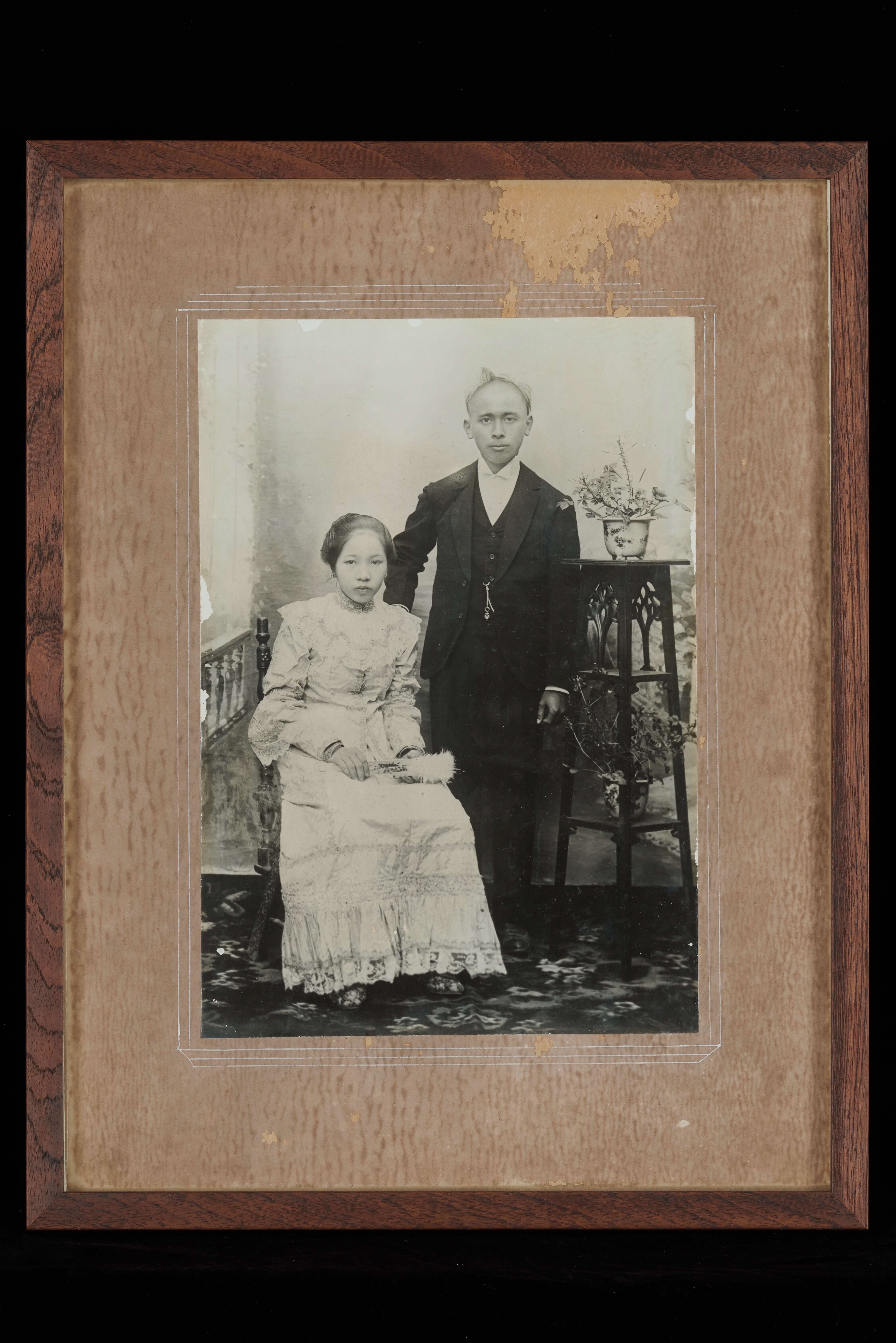

The earliest group of costumes worn by Peranakan women in the exhibition dates to the late 19th century and showed the evolution of Nyonya fashion,starting with the sombre hues of the staid baju panjang and plaid sarong. By the 1910s, women wore bright and transparent European organdies (worn for modesty over a high-necked, long-sleeved white blouse) together with expensive hand-drawn batik sarongs imported from Chinese workshops on the north coast of Java. The Chinese had been involved with batik-making at least since the late 18th century. Production was mostly low quality and by the early 19th century, large quantities of batik handkerchiefs and shoulder cloths were exported to the Straits Settlements. The finest hand-drawn cloths were produced in limited numbers for wealthy patrons in Semarang and Lasem, at the north coast of Java. It was not until the second half of the 19th century that the production of high quality batiks reached quantities large enough for export to Singapore and the region.

Sarong – Java, Sidoarjo, ca. 1920-1925. Signed: Tan Sin Ing. Cotton (hand-drawn batik). Collection of Mr & Mrs Lee Kip Lee.

By the 1930s, the combined baju panjang and sarong was a riot of colour, especially because the batik sarongs were able to match the vibrant hues of the imported organdies after chemical dyes were introduced from Germany. In Singapore, the organdie was called kasa, after a centuries-old trade term for fine gauzes. The Nyonyas added their own flavour to the term, referring to it as kasa gelair (‘glass-like organdie’) after its translucent quality.

Skirt Cloth (Kain panjang pagi-sore) – Java, Kedungwuni, 1930-1950. Signed: Oey Soe Tjoen. Cotton (hand-drawn batik). Peranakan Museum, Collection of Mr & Mrs Lee Kip Lee.

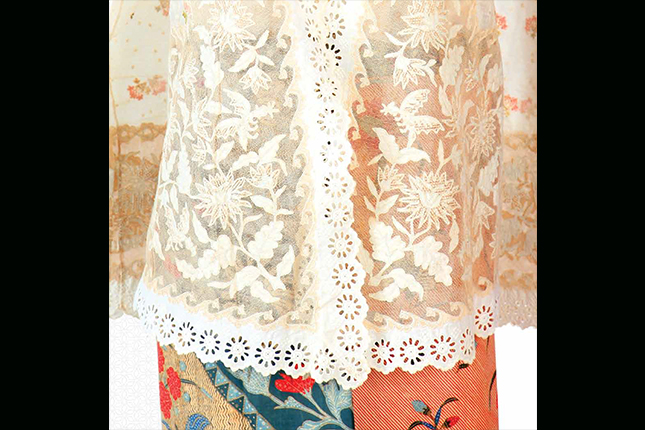

Lace: Threading East and West

In the 18th century, colonial women in the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) added lace to their long kebayas, which they wore with voluminous skirts or saias made of hand-drawn Indian cloths. The word for lace in many languages of the region is derived from the Portuguese term renda, entering even the Peranakan Fujian dialect spoken in Penang, where lace is termed lianla.

By the mid-19th century this fashion was widespread throughout the colonies, and dressing in a white lace kebaya with an expensive cotton batik sarong became a status symbol among European and Eurasian women in the Dutch colony. During this time, European female entrepreneurs in Semarang and Pekalongan in Java began producing high quality batiks to satisfy the huge demand. Taking on many traditional patterns from the old Indian textiles worn by their ancestors a century before, they added many innovative design features to create a whole new genre, today called batik Belanda (‘Dutch batik’ in Malay). Dutch women’s journals advised that a lady living in the colonies required three dozen kebayas and at least a dozen sarongs. There were kebayas specifically for day and night, the latter being less elaborate. On their long sea journeys from the Netherlands to the Indies, women switched from Western dress to sarong kebaya after their ship passed Port Said.4

The sarong kebaya was a costume disparaged by many European travellers. One author described it as an outfit that was “the only practical morning dress, because it can be easily changed two or three times a day – which is becoming to so few; the way the sarong falls straight in the back is particularly angular and ugly, however elegant and expensive the costume”.5

From Emulation to Assertion

Some time around 1900, Nyonya women in the Dutch East Indies began to abandon the long and loose kebaya or baju panjang, and opted instead for the elegant and contoured European white lace kebaya and floral sarong, a fashion they exported to the Straits Settlements. Even at that time, the costume was totally misunderstood. A resident of Kuala Lumpur, in a lively debate on the sarong kebaya organised by the Selangor Chinese Literary and Debating Society in 1904, described the outfit as “an imitation borrowed from the Malay”. The kebaya was “not graceful, nor neat” and the vulgarity of the sarong was “beyond question”, making the Nyonya “a disgrace to modern civilisation”.6

Such criticisms were ignored, since for the next fifty years, the sarong kebaya was the hallmark of Nyonyas in the region. On the other hand, the European women they were emulating stopped wearing the sarong kebaya completely, preferring the modern fashions of the Jazz Age. This period might be regarded as the high point of the Peranakan sarong kebaya. Peranakan women soon added elements that expressed their own identity. Kebayas became increasingly elaborate, and the introduction of the Singer sewing machine lifted imitation lace to astounding levels. Fields of meticulous lace-like work, impossible to achieve with real lace, resulted in kebayas that were breathtaking, cross-cultural works of art. In the 1930s, the finest examples were made from pale cotton voiles, complementing the absurdly complex batiks made in Chinese-owned ateliers in small towns on Java’s north coast. They produced unique pieces for wealthy clients; the batiks were so precious that retailers kept them in safes until buyers were found.

In January 1930, the British textile manufacturer Tootal trademarked their signature cotton voile known as Robia, and by April of the same year it was advertised for sale in Singapore at Whiteaway, Laidlaw & Co.7 Among Nyonyas, this name became synonymous with the voile used for kebayas, and has deep nostalgic resonance for many Peranakans today.

Towards the middle of the century, the colours of the sarong and kebaya became increasingly vivid and intense. After the war, the prohibitive expense of lace and the desire for stronger hues and dramatic modern patterns resulted in kebayas with larger motifs and sarongs drenched in contrasting colours.

To the wearers, the costume was a very private indulgence. Like many luxuries, the finest aspects of workmanship and quality were expressed in details that were hidden when worn. For much of this golden age, the sarong kebaya was an outfit for the home, important family occasions and visits to the residences of close friends and relatives. When a nyonya had to put on a public face – at colonial events or occasions when there would be people of other communities – she frequently preferred the Chinese cheongsam. However, with over 50 examples on display at the Peranakan Museum, the iconic sarong kebaya were finally nudged back into the limelight.

Skirt cloth (Kain panjang pagi-sore) – Java, Kedungwuni, ca. 1950-1960. Signed: Na Swan Hien. Collection of Mr & Mrs Lee Kip Lee.

Peter Lee is Guest Curator of ‘Sarong Kebaya: Peranakan Fashion and its International Sources’.

Notes