Scents of Singapore’s History

A fragrance company is donating old, familiar smells to enhance visitors’ experience of museums.

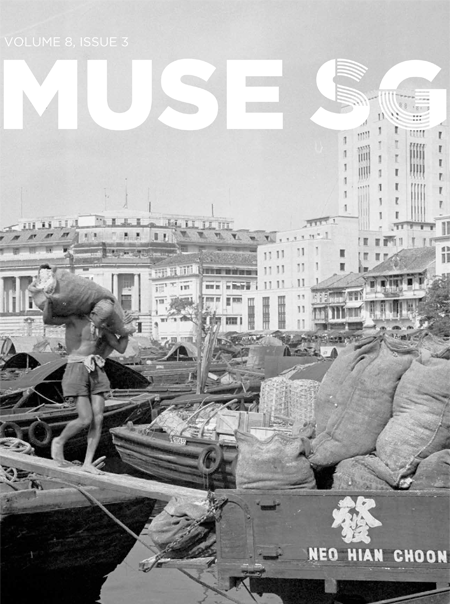

The Singapore River smelled bad in the 1970s. Hawkers, squatters, and manufacturers crowded the river banks and treated the river as if it were a toilet and bin centre. In 1977, the government started cleaning it up. Over the next 10 years, it spent $170 million on the river — first relocating the people and businesses and then dredging out the stinky mud.

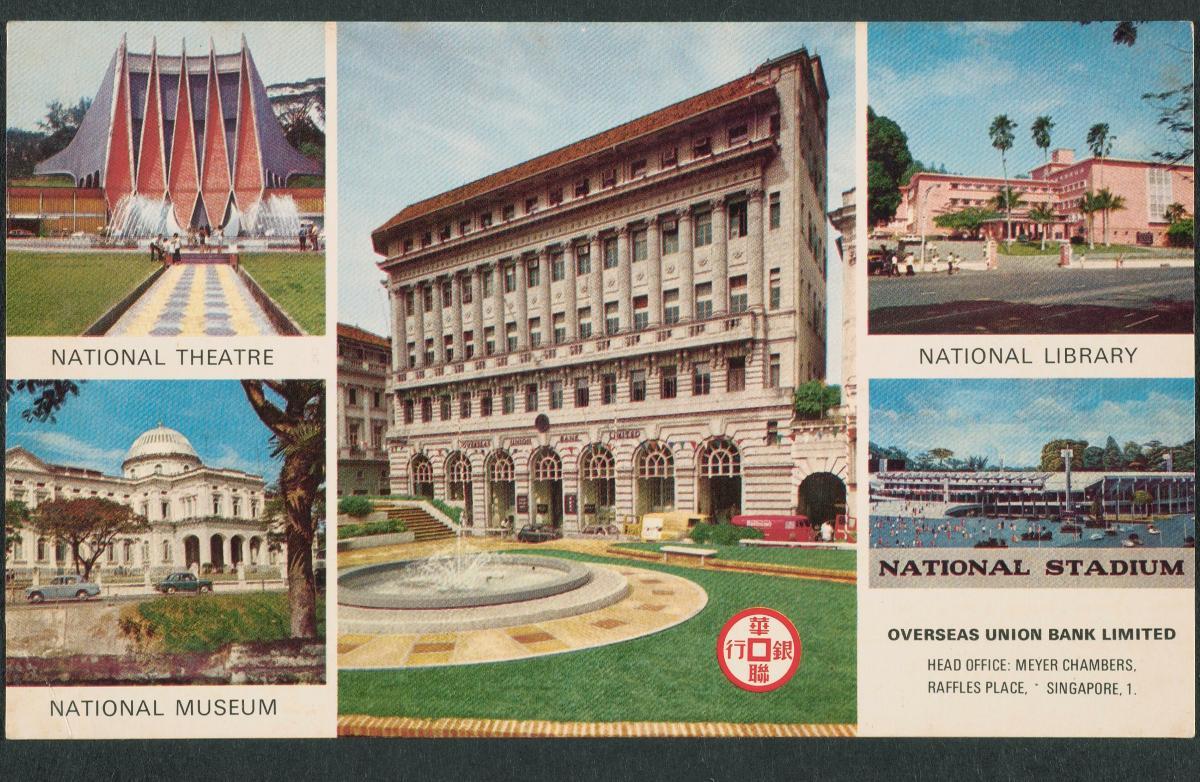

So, it was peculiar to many when the National Museum of Singapore revived the acrid river smell for its permanent galleries during Singapore’s 50th anniversary in 2015. Repulsive it may be, but the museum hoped this stench would evoke sweet memories of a bygone era. After all, the Singapore River has witnessed many of this country’s significant economic and social activities.

Donated scents

Swiss fragrance company Givaudan helped the museum create the sensorial exhibition. “It was a very natural collaboration between us because scents have such amazing powers to transport us back to a memory, a place or a time in our lives,” says Ben Webb, the company’s Head of Fragrance Division in Asia Pacific. This power has to do with how the brain areas are connected. The olfactory bulb where the smell is understood, Ben explains, is closely linked to the brain regions that handle memory and emotion. This is why elderly visitors to the gallery experience a flood of memories from before the 70s, while those much younger have a deeper experience of Singapore’s history.

Because the stench of the river is no more, Givaudan’s perfumer, Sreevidhya Venkatesh, relied on archival research and oral histories to identify the characters and activities that might have contributed to this unforgettable smell. She eventually narrowed it down to the spice traders, the cooked-food hawkers, and the diesel-powered boats.

Besides the smell of the Singapore River, Givaudan also donated other scents to the museum. Visitors entering a gallery on the city’s colonial past can smell “Afternoon Tea” just as the British would have, while a “Tembusu flowers” scent accompanies an exhibit that looks at Singapore’s greening efforts. The latter came to the attention of perfumer, Claude Charmoille, when he first moved to Singapore. He noticed the scent during his evening walks and managed to trace it to this towering tree species that is indigenous to Singapore. For him, and probably many others, the tembusu fragrance evokes images of Singapore as a garden city.

Givaudan not only emulated environmental scents for the museum, but also created a new fragrance to mark Singapore’s jubilee. The limited-edition unisex perfume, City, is made from a blend of local ingredients ranging from orchids to ambrettes so that it encapsulates this city’s “energy and dynamism”, says Ben.

Received POHA

The National Heritage Board honoured Givaudan with a Patron of Heritage award in recognition of the company’s efforts to enhance visitors’ experience of Singapore’s history at the National Museum. Ben says Givaudan is very happy to contribute its technical and creative expertise to the National Museum. It has also done so for the Malay Heritage Centre, Taman Jurong’s community museum, and a Scents and Memories workshop at the Singapore Heritage Festival 2016.

“Heritage is especially important to Givaudan as our company has been around for almost 250 years,” adds Ben.

Besides contributions by corporations like his, Ben says the local community plays an important role in keeping heritage alive. Givaudan depended on it for guidance and feedback when recreating scents for the Malay Heritage Centre recently.

“The public is very much a part of creating connections to the nation’s heritage either by passing on their own memories or by creating new ones whenever they visit the museums,” says Ben.

By SHEERE NG