The surviving books and manuscripts from the Malay World, particularly from the 14th century onwards, contain a captivating glimpse into the literary manifestation of cultural practices of the community. Beyond historical documentation, these literary treasures provide an insight particularly on topics such as magic, divination, and healing.

This article features a collection of selected manuscripts and rare books from our Singapore National Collection, including an in-depth view of one of the artefacts from the collection of the Malay Heritage Centre, the Jimat scroll. Together, these artefacts demonstrate the significance of magic and divination in the Malay world using religious scripture and illumination, and the ways in which science, cultural practice, and religious beliefs work together to endow objects with talismanic and protective powers.

The Influence of Islam and the Use of the Jawi Script

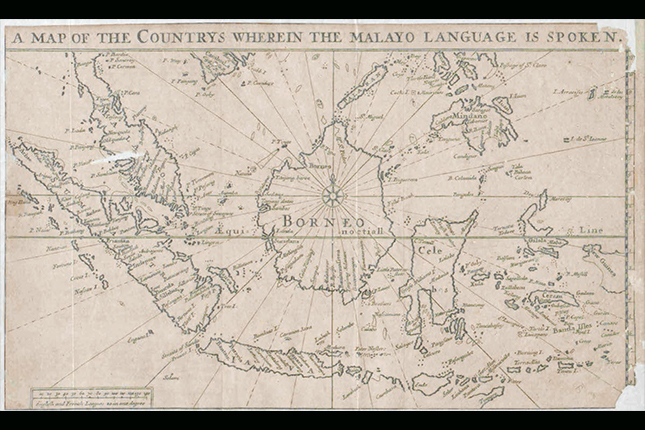

Malay works were traditionally experienced orally and aurally prior to and well after the adopting of manuscript practice, with early Malay manuscripts employing Indic scripts and lettering systems such as kawi , pallava and nigari . These early lettering systems were carved and inscribed on stones and palm leaves, and also engraved on monetary coins and jewellery. The arrival of Islam in the Malay Peninsula during the 12th to 13th century – through religious scholars, pilgrims and also arguably through merchants and traders from India and the Persian Gulf – had great influence on the existing literary tradition of the Malay world. The influence of Islam introduced the Arabic script, which was later adapted into what is known as the jawi script to include specific Malay words and phonemes.

Beyond introducing the jawi script and the culture of writing, Islam also heavily influenced the narratives that were written and shared with the community. Stories regarding key Islamic figures, such as those relating to Prophet Muhammad and his companions, and other tales relating to Islamic morals and ethics, were often localised for audiences in the archipelago.

This section showcases a series of selected literary works, all of varying content and function, that utilise the jawi script. Click here to explore other artefacts in our National Collection, from heritage objects to modern 20 th century textbooks, which feature the jawi script.

Divination Manuscripts in the Malay World

Manuscripts of the Malay world documented the blurred distinction that existed between magic and religion. Books on magic and divination, as with other respected texts and manuscripts, were referred to as kitabs and held in high regard as they were perceived to be part of the literary corpus of the religion.

One form of Malay manuscripts were manuals for divination and healing. These manuscripts contain many of the tools that “magicians” used in carrying out their work, including incantations to recite, instructions for casting spells, methods to create talismans and endow them with protective powers, as well as charts, tables, and other techniques for fortune-telling and divination. There is also a close relationship with religion; Qur’anic texts and prayers were often included in these manuals and talismans, as they were believed to call on protective powers. These elements were reconciled with Islamic precepts and teachings, as it can be observed through how many of the incantations and talismans had involved the use of the Qur’an.

Malay “magicians” were often engaged by members of their communities for the practice of divination. Such acts can be defined as attempts to predict future events or gain information about the “unseen”. Divination manuscripts may be used for various purposes including everyday practical concerns and tasks, such as determining what dates and timings are ideal for building houses or planting crops.

Although divination was a common practice in the region, divination manuscripts tend to differ from each other according to the magicians’ preferences. Notes in their manuscripts tend to be specialised knowledge that may only be privy to the magician who owned or used them. Nonetheless, these manuscripts usually contained similar information on numerology, astrology, auspicious or inauspicious times, omens, dream interpretation, physiognomy, sortilege, and bibliomancy.

The talismanic inscriptions and designs present in these manuscripts were thought to contain great mystical power that may be utilised to affect the intended purpose of the user. The belief of divination manuscripts carrying the talismanic properties resulted in several types of divination manuals, one of which is in the form of a talismanic scroll. Talismanic scrolls were created or preferred by some practitioners as they were small and easy to transport.

Jimat Scroll - Malay Manuscript

2019-00571

circa 1900

Malay Peninsula

Collection of Malay Heritage Centre

This talismanic scroll, dating from around 1900, is believed to have been used to protect or benefit the owner or user. In Malay, these talismans are generally called azimat or jimat, although a protective amulet may also be referred to as a tangkal. An in-depth look at this jimat scroll is elaborated in the next section of the article.

This section showcases several selected divination manuscripts in the National Collection. Click here to explore more divination artefacts from our National Collection. Click here to explore other manuscripts in our National Collection, that covers a wide range of subject and presented in various scripts.

The Protective Power of Talismans

Beyond divination manuals, the use of Qur’anic texts and verses were also evident in talismans, amulets and charms, which were also prevalent throughout the region. Small objects, most either carried or worn, were believed to be imbued with magical powers for various purposes such as protection, healing of ailments, and even attracting wealth or love interests. Their protective properties were said to be imbued by the bearing of Qur’anic inscriptions, as well as the use of names of prophets, and other imageries. Many Muslims prescribed to the idea that any object inscribed with the word or name of Allah or God will protect the owner or any individual who reads, touches, or dons the object. Thus, the individual would have the power to ward off evil by the protection of God.

This section showcases a selection of talismans from the National Collection in various forms. Click here to explore other talismanic items in our National Collection.

The Jimat Scroll

Divination manuals in the Malay world include what is commonly called jimat scrolls – talismanic scrolls believed to grant protection, healing or benefit through magic and sorcery. Small enough to be carried in one’s pocket, a jimat scroll accords the owner the ability to use or recite the incantations with ease of accessibility and convenience. This section takes an in-depth look at a jimat scroll from the collection of the Malay Heritage Centre.

Jimat Scroll - Malay Manuscript

2019-00571

circa 1900

Malay Peninsula

Collection of Malay Heritage Centre

As with other divination manuscripts and talismanic items, the surface of this jimat scroll is covered with prayers, signs, numbers, and decorative motifs on both the internal and external sides. Encased within a two-part wooden cover, this scroll shows signs of wear, with its dating estimated to be at the early 20th century.

Six buduh or magic squares – grids that contain numbers and alphabets – are inscribed across the scroll. In the Islamic tradition, these grids often contain the abjad letters ba (ب), wau (و), dal (د) and ha (ح) to form the word buduh. Variations of the buduh magic square in Malay manuscripts are catered to the needs of the user. Examples of day-to-day uses include providing protection for oneself, attracting customers to one’s business, easing childbirth, easing ailments, ensuring safe passage of letters and packages, and protecting one’s boats and during journeys and transportation. It is even used for divination purposes to determine suitable dates and timings for voyages and customary events.

Accompanying the texts are illuminations, such as frames containing scrolling foliage and floral patterns adorned with colours. These artistic features and decorative flourishes of the scroll shows a strong connection to aspects of Malay decorative and performing arts in the peninsula, such as woodwork and theatre.

Here are some close-up images of portions of the scroll, accompanied with selected Malay transliteration and explanations.

Illuminations and Imageries

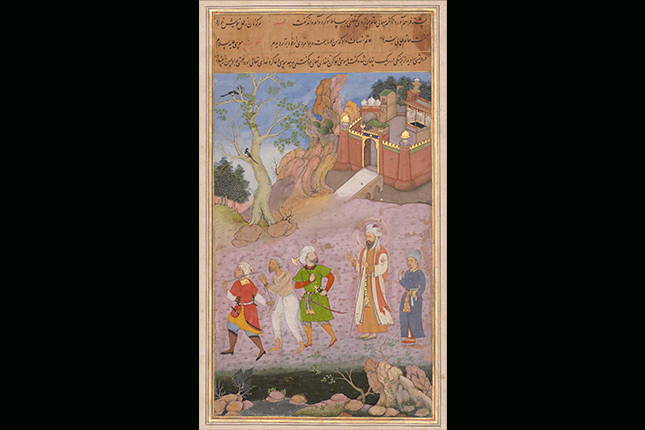

In general, Malay literary manuscripts lacked illuminations. However, selected manuscripts, such as devotional works of the Dala’il al kayrat of al-Jazuli and kitab maulid contained beautiful illustrations, more specifically stylized representations of the symbols of holy cities of Mecca and Medina. This is in accordance with Islamic art tradition, where figurative representations and depictions of living creatures are often excluded. Instead, geometric patterns and arabesque motifs are more prominently featured. Such decorations are typically found in title pages, although the more ornate manuscripts may have artistic features throughout the folio. The rectangular frames that bordered the texts may be embellished with arches and floral and foliage motifs in an intricate meandering pattern. Similar motifs can also be found in other Malay decorative arts, such as woodcarving, silverwork, embroidery, textiles, and sculptures.

This section highlights a selection of manuscripts from the National Collection that feature illuminations. Click here to explore other illuminated manuscripts in our National Collection.

The Making of Manuscripts – Materials and Techniques

The materials and techniques used for the manuscripts often hint at their place of origin. Most extant manuscripts are only dated from the 17th century, as earlier works had degraded due to the humidity of the region. Manuscripts made from materials such as bark and bamboo were able to survive for longer. Some manuscripts were even inscribed in stone.

The paper used for manuscripts tend to be manufactured in Europe and brought over to the region, as there was limited paper-making tradition in the Malay archipelago. Italian paper was also brought over from the Middle East. For the text and writing, black ink was commonly used, while blue, red, and yellow inks were also used as decorative elements or to contrast certain texts against the black. In later manuscripts, watercolour was also used.

Most manuscripts were not bound, but are instead loose, or sewn together. Loose leaves were held together using pieces of cotton or leather covers, depending on the region. Other methods used to keep these manuscripts together were folding-book, which was mainly used in mainland Southeast Asia, or Islamic binding, which was inspired by manuscripts from other Muslim communities.

This section highlights several artefacts that are related to the making of manuscripts. Click here to explore other artefacts in the National Collection related to book binding.

Acknowledgements

Written by:

Afiqah Zainal, Manager (Cataloguing), Knowledge & Information Management, Heritage Conservation Centre

Contributors:

Wan Nur Syafiqa, Research Assistant (Cataloguing), Knowledge & Information Management, Heritage Conservation Centre

Alex Soo, Asst Manager (Photography), Knowledge & Information Management, Heritage Conservation Centre

Zinnurain Nasir, Assistant Curator, Malay Heritage Centre

Syafiqah Jaafar, Assistant Curator, National Museum of Singapore

Advice and assistance:

Ho Swee Ann, Senior Manager (Cataloguing), Knowledge & Information Management, Heritage Conservation Centre

Sufiyan Hanafi, Manager, Collections Management, Heritage Conservation Centre

Notes

References:

- Al-Saleh, Y. (2010, November). Amulets and Talismans from the Islamic World. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. Retrieved January 29, 2023 from http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/tali/hd_tali.htm

- Daneshgar, M. (2015). The divinatory role of the Qurʾan in the Malay World. Indonesia and the Malay World, 44(129), 123–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639811.2015.1044740

- Gallop, A. T. (2010). The amuletic cult of Ma’ruf al-Karkhi in the Malay world. In Writings and Writing from Another World and Another Era, 167–196. Cambridge: Archetype. Retrieved January 29, 2023 from https://www.academia.edu/5298583/The_amuletic_cult_of_Ma_ruf_al_Karkhi_in_the_Malay_world

- Kratz, E. U. (2002). Jawi spelling and orthography: A brief review. Indonesia and the Malay World, 30(86), 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639810220134647

- Maier, H. (2008). Explosions in Semarang: Reading Malay tales in 1895. Bijdragen Tot De Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde / Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia, 162(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1163/22134379-90003672

- Osman, M. T. (1972). Patterns of supernatural premises underlying the institution of the Bomoh in Malay culture. Bijdragen Tot De Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde / Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia, 128(2), 219–234. Retrieved 29 January, 2023 from https://brill.com/view/journals/bki/128/2-3/article-p219_3.xml

- Proudfoot, I. (2003). An Expedition Into the Politics of Malay Philology. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 76(1), 1–53. Retrieved 29 January, 2023 from https://www.jstor.org/stable/41493486

- Putten, J. (1997). Printing in Riau; two steps toward modernity. Bijdragen Tot De Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde / Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia, 153(4), 717–736. https://doi.org/10.1163/22134379-90003922

- Savage-Smith, E. (2004). Magic and divination in early Islam. Ashgate.

- Shaw, W. (1976). Aspects of Malaysian magic. Muzium Negara.

- Winzeler, R. L. (1983). The Study of Malay Magic. Bijdragen Tot De Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde / Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia, 139(4), 435–458. Retrieved 29 January, 2023 from http://www.jstor.org/stable/27863530

- Yahya, F. (2016). Magic and divination in Malay illustrated manuscripts. Leiden: Brill.

.ashx)

.ashx)

.ashx)

.ashx)

.ashx)

.ashx)

.ashx)