MUSESG Volume 14 Issue 1 - July 2021

Read the full MUSE SG Vol 14, Issue 1.

Phyllis Koh has been a paper conservator at the Heritage Conservation Centre (HCC), National Heritage Board, for 14 years. Koh graduated with a Bachelor of Science (Life Sciences) from the National University of Singapore, and a Masters of Conservation in Fine Art from Northumbria University, UK. She is currently the head of paper conservation in HCC, where she leads a team of paper conservators. Her interests include Southeast Asian materials and artworks, such as 20th-century Vietnamese paintings.

Watch: Meet the Expert: Phyllis Koh

What was a typical day in the life of a paper conservator like before the pandemic?

There is usually a myriad of different activities in the day, like when we are in the paper lab, we could be carrying out photo-documentation and treatment on the collection such as documents, drawings, maps, prints, etc. We could also be supervising framers on the mounting and framing of paper works that will be displayed at the exhibitions. At times, we may have impromptu gatherings around the lab table to quickly discuss on a difficult treatment or to distribute exhibition work. Besides exhibition projects, a few of us might be involved in research projects or at the museums to carry out installation work onsite.

How has the pandemic changed the way you work, given how hands-on your work is?

I think now we all must be even more conscious of how we plan and spend our time, to balance the administrative needs and bench work. For example, I tend to focus more on the critical hands-on work on the designated days that I’m at the Heritage Conservation Centre and try to clear as much administrative work when I work from home. I think the pandemic is also a good opportunity for my colleagues and I to examine if there are areas in which we could be more efficient and still be able to meet the exhibition deadlines.

Have there been any significant changes in the paper medium over time that have also fundamentally altered the way paper conservation is done?

In the collection, I have come across the earlier handmade rag (cotton) papers that are of very good quality; later on, modern papers were mostly machine-made with wood pulp which produced lower quality papers. However, even with changes in the paper medium over time, the agents of deterioration or factors that cause damage to paper collections are largely still the same.

People and non-ideal environments are still the major factors causing damage, such as rough handling, folding, gluing, high humidity, etc. By and large, I would say that we still use similar techniques in conserving these paper items from different periods of time. However, I have also noticed that there is a lot more awareness on sustainability, health and safety concerns on the materials used in paper conservation techniques. I think with the growing contemporary paper works in the collection, we also need to look outwards, be more creative and open about conserving paper works and see what new techniques could be adopted.

What is one of the most memorable items you’ve worked on?

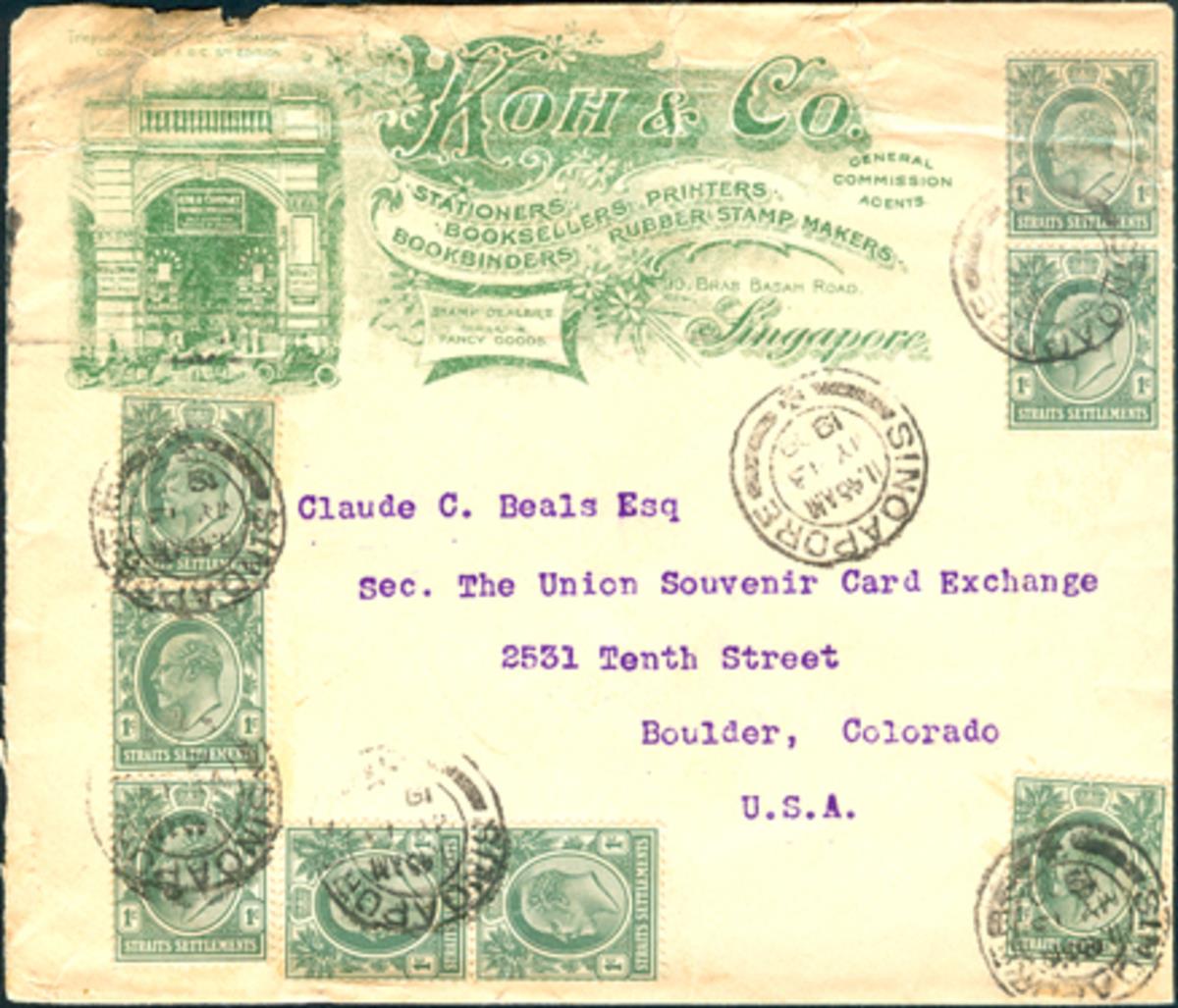

Nine years ago, I treated a Thai manuscript (2012-00734) from the late 19th to early 20th centuries which had extensive insect damage. It left a deep impression on me because I had never seen such extensive damage by silverfish. Besides the major losses on many pages of the manuscript, it came with a lot of insect frass (insect faeces) and flattened silverfish carcass in between the pages.

While there was a lot of work involved in stabilising the manuscript for an exhibition, I had a deep sense of satisfaction treating this artefact. I removed the insect frass via vacuuming and scraping, including the dry silverfish carcass. I enjoyed in-filling the losses as well, including repairing the cover, so that the work could be safely handled and displayed in the museum thereafter.

Having been in the field for 14 years, is there a philosophy in conservation work that you might have found yourself inadvertently applying to life in general?

I think there are so many things in conservation work that can be applied to life! In the treatment process, we would usually examine the work in detail, consider the treatment aims, options, and plan our time to carry out treatments, especially for major ones. I think the greatest takeaway from that would be not to lose the big picture while looking at the finer details, to weigh the options we have, planning well ahead and not to assume things. I think being a conservator has also made me a better person as compared to 14 years ago—I am more organised and have a better sense of order, which is also important for housekeeping at home!

What do you think is the biggest challenge in the field of (paper) conservation today?

I think one of the biggest challenges today is that, increasingly, conservators have to find ways to stay relevant and adapt to the changing landscape. Traditionally, the conservation profession is very hands-on, but now we have to get used to being more front-facing, especially with the rise in digital offerings, increased demand for public access and outreach programmes—for example, the use of social media in the cultural sector.

Besides having conservation skills and knowledge, I think we will also need to influence and communicate more effectively with the various stakeholders. Hopefully, having an openness to acquiring new skills, a broader view and a better understanding of our organisational context will help conservators find creative ways to rise to the challenge in this brave new world!

Please share with us some tips for protecting our books in Singapore’s climate!

Unfortunately, the climate in Singapore is really humid and many of the books nowadays contain wood pulp, which would easily allow acids to form in the paper. As such, our books tend to discolour easily or have foxing (yellow spots). As much as possible, keep your books far away from food sources or areas with high moisture. If possible, make sure that there is enough ventilation and that they are not closely packed.

If you intend to store them in boxes, consider archival materials that are acid-free. It is recommended to have a good dusting regimen if they are kept in open storage areas. Lastly, one can consider a digital dry box if they have precious books that they wish to keep at a lower and stable relative humidity.