TL;DR

MUSE SG speaks to Noora about her unconventional journey to becoming a curator, as well as her thoughts on the evolving role of museums and public perceptions on heritage.

MUSE SG Volume 15 Issue 02 - July 2022

Read the full MUSE SG Vol. 15 Issue 2

Image Above: Noorashikin Zulkifli with the Asian Civilisations Museum’s pop-up exhibition Apa Khabair? — Peranakan Museum in the Making in the background.

Watch: Meet Senior Curator Noorashikin Zulkifli

Noorashikin Zulkifli, a veteran curator with the Asian Civilisations Museum (ACM) specialising in Islamic art, has been with the National Heritage Board (NHB) for more than a decade. Involved in numerous exhibitions and programmes throughout her career with various cultural institutions Noora most recently worked on the pop-up exhibition Apa Khabair? - Peranakan Museum in the Making held at ACM.

Noora, please tell us about your path towards becoming a curator at a national heritage institution!

I’d never imagined where I would be now in terms of my career — looking back, it was a meandering journey with different stops along the way. I have always been interested in the arts, even back in school. My first interest was theatre. After junior college, I did not attend university right away but got involved in local theatre groups such as The Necessary Stage and Teater Ekamatra in both onstage and offstage capacities. As an 18-year-old then, these experiences were very exciting.

That sparked my interest in arts management, which I took up in university, and it was then I discovered my next love: modern contemporary art. Thus, I pursued a master’s degree in interactive media and critical theory at Goldsmiths, University of London. After I returned to Singapore, I wondered if I wanted to practise as an artist; yet I was also interested in putting together a production.

I had the opportunity to join the Singapore Art Museum (SAM) as a programmer after my studies and that gave me the opportunity to put on spectacular live events, as well as understand how curating and programming complement each other. SAM was also where I tried my hand in curating for the first time. It was an eye-opening experience working with such a huge gallery, dealing with artists, and building an art exhibition. After SAM, I taught media theory at LASALLE College of the Arts for three years.

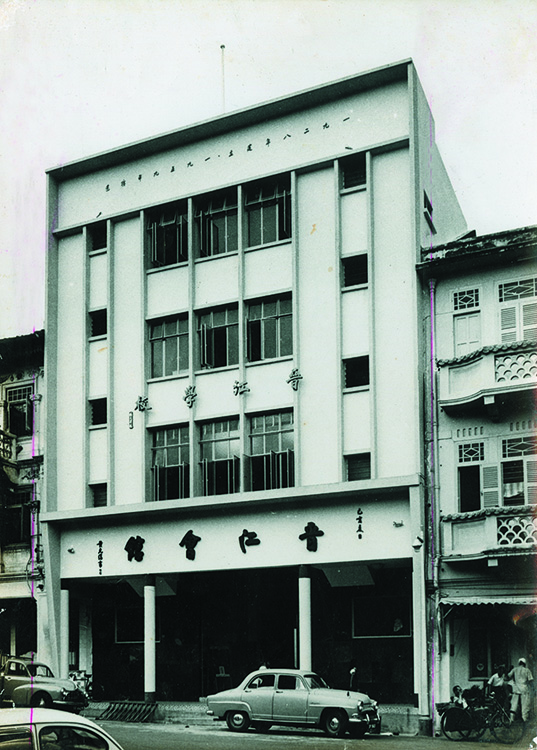

A turning point arrived when I was engaged as a researcher to work on the revamp of MHC in 2009. The work made me reflect on various historical subjects, as the questions and issues that were being addressed for the project necessitated greater examination and a deeper look into the past. I joined MHC officially the following year as a curator and worked there until 2015.

One of the things I experimented with at MHC was community co-creation— setting up ‘clinics’ with community groups to discuss exhibition-making. I adopted this co-creation model for the Se-Nusantara series at MHC that highlighted different ethnic groups. It aimed to provide communities with the space to have their own voice. It was a truly enjoyable process; it challenged what I thought I or they knew, but I realised in the end that it’s really all about listening.

After these ‘detours’, I joined ACM as a curator in 2015 while it was undergoing a revamp and worked on the Islamic art gallery.

What have you learnt from working on artefacts at ACM?

I came to appreciate how details of an object can be used to draw out rich stories, and I also became more acquainted with a variety of media and materials. Having the privilege of touching objects that have lasted, say, 500 years, made by people during that time — that never ceases to amaze me. That someone living in an environment with far less technology than we have today, was able to rely on their own skills without computer-aided design, and yet could execute intricate details so masterfully — it blows my mind!

I was also exposed to other aspects of curation that were less ‘public-facing’— collection acquisition and development, which I found to be very meaningful.

Humans forget and our memory is fallible. Having the National Collection as a repository of works preserved from centuries ago is an incredible resource to rediscover techniques or knowhow, as well as to rediscover peoples and their stories.

Can you share with us an artefact that has left a lasting impression on you?

A calligraphic tile from the 13th century. The brilliant metallic hues that can be achieved are amazing to behold, especially in terms of how a variety of shades can be seen depending on how light hits the surface. Considering the difference in scientific knowledge and methods between now and then, I’m amazed at how the artist(s) figured out what compounds or elements to use and the innovation it took to create such a beautiful effect.

Given how long it takes to throw, mould, decorate and fire a piece of ceramic, it must have been quite a long road in terms of experimentation— imagine the amount of patience, focus and dedication required!

.ashx)

In your relatively long career spanning many different institutions, what changes have you perceived in terms of public consciousness relating to heritage and history?

Since my time at MHC, there is now a much greater public appreciation for heritage. At MHC, we relied a lot on the community coming forward with their stories, but sometimes they didn’t, not because they didn’t want to, but because they didn’t know what they had.

However, that is changing. People now have a better understanding that these stories are valuable and meaningful not only to themselves but also to other people, and that sharing them publicly can be a good thing. People are more invested in their identities and cultural heritage. They realise they can take ownership of their past, and this development has been very heartening and encouraging. Hopefully the interest continues to grow.

Although NHB is the official custodian of our heritage, it shouldn’t be just us; everyone needs to play a part in it. We can’t cover every story. The only story you can take control of is your own.

Expanding on what you said about people taking ownership of their own stories, how do you view the role of exhibitions today in terms of plurality of voices?

In the first place, an exhibition should never be an end point — but the start of a journey. Ideally, people should go to exhibitions and be inspired to embark on their own journeys of exploration. This process of discovery doesn’t end in the gallery.

For me, museums are incubators, forums and facilitators. We focus on the larger sweeps of art history. These are frameworks for people to situate, make sense of, or place their own personal histories. From time to time, we have the opportunity to highlight these histories. Museums ought to be a resource in that way, but not an encyclopedia.

A shift that is occurring in the cultural sector not just locally, but globally, is that it is all about relationships and engagement. I am not wedded to the idea of the museum or any institution being the ‘supreme’ authority. I believe in plurality—and that is my ideal vision of the world. Museums are just one estate. There are things that museums do well, such as having the resources to conserve materials. But ultimately, we need to recognise that museums are only one of the players among many others.

“Although [the National Heritage Board] is the official custodian of our heritage , it shouldn’t be just us; everyone needs to play a part in it. We can’t cover every story. The only story you can take control of is your own.”

What is the greatest lesson for you in terms of your career path?

Right now, the perception of a curator is still very rooted in being an academic. But I would like to make the point that there isn’t just a single path. I have learnt so many skills through the roles I’ve played in various points of my life and in different settings.

In theatre, for example, one is trained in storytelling and scene-setting, and these are skills that are transferable to other kinds of work, such as exhibition-making. Also, I marry my contemporary art sensibilities with traditional art and historical objects, turning up new ways of seeing and contextualising. There are so many different pathways!

Don’t just limit yourself to one thing. Instead, seek to adopt a multidisciplinary thinking. When I was in theatre, improvisational games were often part of practice and rehearsals — being exposed to these experiences helped me become more agile in my perspective. I am not so upset if things do not go according to plan. We need to think laterally and have multiple solutions.

From being involved in small, independent collectives and projects in my younger years to a national institution now, there is still some of the DIY (do-it-yourself) spirit in me. For example, I don’t get too fussed about who needs to be doing what, in terms of the hierarchy of roles. We just do what needs to be done to make something happen — including an exhibition. That, for me, is what I value. Like, I would not be averse to sweeping the floor!