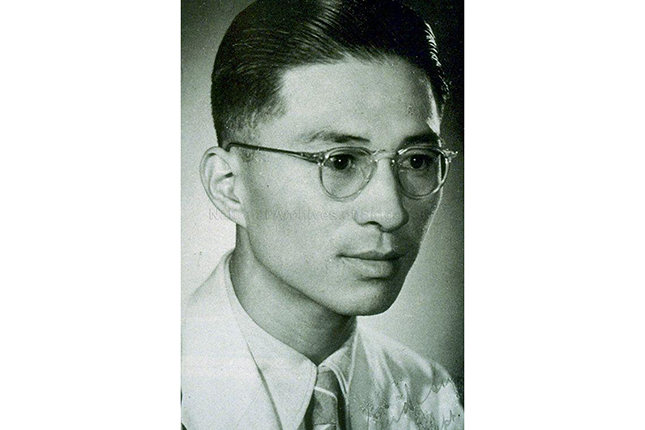

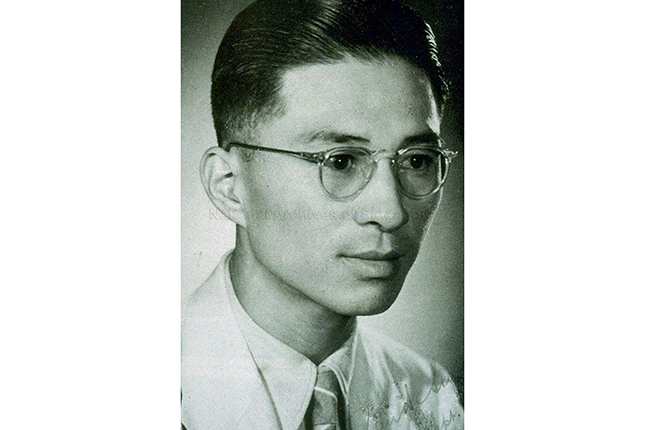

Portrait of Lim Bo Seng (c1941–1944. Image from the Lim Leong Geok Collection, National Archives of Singapore)

Portrait of Lim Bo Seng (c1941–1944. Image from the Lim Leong Geok Collection, National Archives of Singapore)

Lim Bo Seng, the first son of contractor Lim Loh, was born in a 99-room family housing complex in Fujian’s Nan’an County in China.1 He left for Singapore at 16 and studied at the prestigious Raffles Institution2 where he was classmates with individuals such as Yusof Ishak, the future president of Singapore.3

In 1929, Lim cut short his studies at the University of Hong Kong to take over his father’s businesses, one of which was a well-known construction company involved in the erection of major landmarks such as Goodwood Park Hotel, Victoria Memorial Hall and Old Parliament House.4 Lim’s business acumen put him in good stead to manage and grow his father’s businesses. As a result he also became a prominent merchant.5 On top of this, Lim served in key positions in a number of associations such as the Singapore Contractors Association, the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce and Industry, and the Singapore Hokkien Association.6

Lim married teacher Gan Choo Neo in 1930.7 She bore him eight children, one of whom died at a young age.8 He was a loving father, taking his children to High Street on weekends to read and buy books at Ensign Bookshop before adjourning to Polar Cafe for cake and ice cream.9

When war broke out in China, Lim stepped forward and took on an active role in resisting Japanese advances, earning himself a distinguished place in history as one of Malaya’s foremost war heroes. But his anti-war efforts required great sacrifice. When Singapore fell to the Japanese, Lim found himself having little choice but to separate from his beloved family.

Clandestine missions

Lim’s anti-war efforts, where he organised fundraisers and protests, began in the 1930s, before the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese war.

In December 1941, Japanese troops infiltrated Kota Bharu in Malaya in an amphibious attack. Alarmed, the British called on Lim to help bolster Singapore’s defence infrastructure. As head of Labour Services of the Overseas Chinese Mobilisation Council, he gathered 10,000 men to erect defences, run key services for the population, and blow up the Causeway — a means in which the Japanese could storm Singapore.

With the Japanese on Singapore’s doorstep, arrangements were made for Lim and his family to leave for their safety. However, with the Japanese sinking evacuating vessels, Lim made the call to have them stay on in Singapore, choosing instead to leave their side.

In a diary entry dated 11 February 1942, just days before the fall of Singapore, Lim wrote that the decision to separate pained him greatly. “To leave the dear Mrs behind at the mercy of the enemy would go very hard against my own conscience. On the other hand, to remain with the family in the event of enemy occupation, would not in any way improve the situation but my presence may even make their lot very much harder.”

He added that his children were "too stupefied to realise what was happening” as they kissed him goodbye. “I shall never forget the tear-stained faces as long as I live. If there is anything I could do to make up for what they were then going through, I shall not spare myself to carry it out.” It was the last time he would see them. .

Lim left soon after by sampan, observing in his diary that the sky was lit up by enemy fire in three directions — Pasir Panjang, Serangoon and Bukit Timah.10 By morning, Singapore was “enveloped in a pall of smoke”.

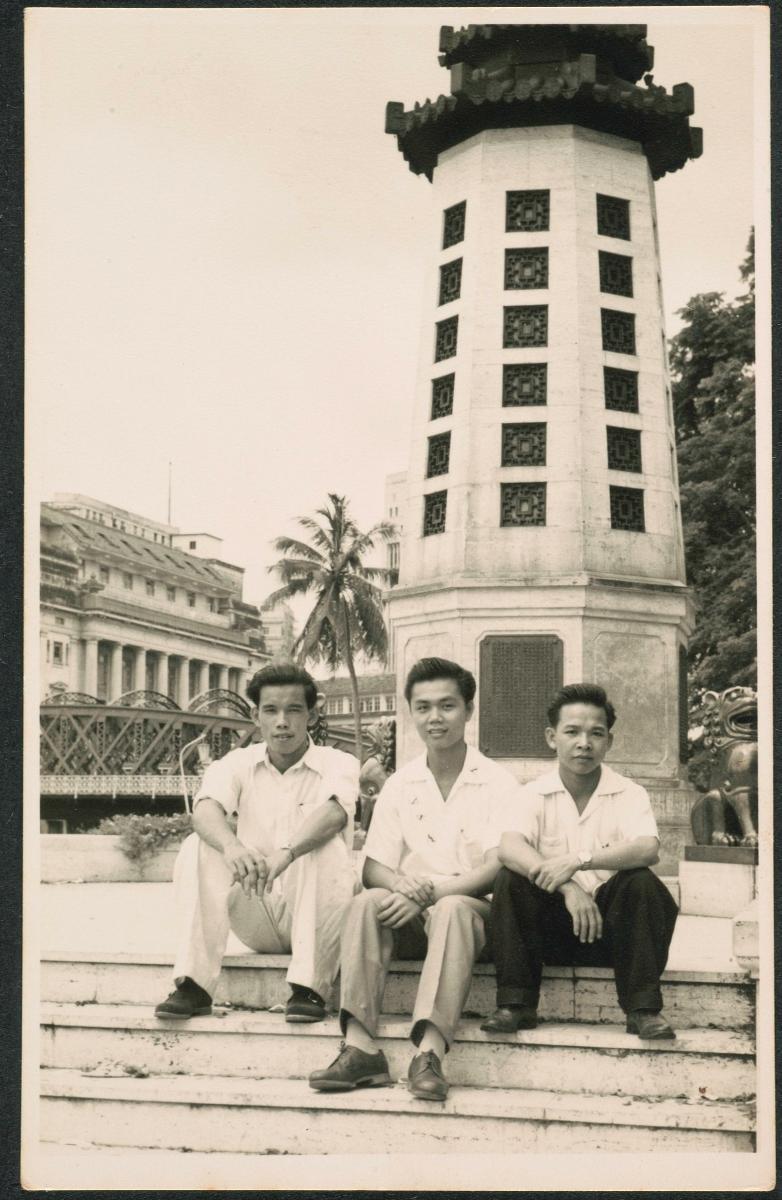

Lim eventually found his way to India, joining Force 136, a secret service unit established by the British and Chinese governments to recapture Singapore.11 He was responsible for recruiting Chinese espionage agents who could blend in with locals to gather intelligence.12

Upon completion of their training, teams from Force 136 boarded a Dutch submarine from Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) to re-enter the Japanese controlled territory of Malaya.13 Lim was among them. While in Malaya, Force 136 attempted to collaborate with the area’s main resistance movement, the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army. It also set up a covert network to gather intelligence.14

Later, following some blunders and a betrayal, information was divulged to the Japanese which led to the arrests of Force 136 agents. Lim, who had left the group’s Bukit Bidor camp to raise funds and expand its intelligence network, was also arrested.15

Lim was mercilessly starved and tortured for information by Japanese military police at the Batu Gajah Gaol where he was incarcerated. They failed to break him. Despite his own plight, Lim shared his meagre food rations with fellow prisoners. Compatriots who witnessed his last days in prison said he had been "reduced to a bag of bones".16 He eventually died of malnutrition, dysentery and torture at 35.17 Wrapped in a tattered blanket, he was taken away in a wooden cart and buried in a mass grave near the prison grounds.18

A hero’s return

In Singapore, the Japanese who were baying for blood, were successful in hunting down and killing eight of Lim’s relatives living at 855 Serangoon Road — a compound comprising three houses built by Lim Loh.19 Lim’s wife, however, managed to outwit them, moving her family from one hideout to another. At one point, she even sought refuge at St John’s Island.20

Following his unceremonious burial in Batu Gajah, Lim’s remains were brought back to Singapore.21 After a funeral at City Hall, he was laid to rest with full military honours on a hill overlooking MacRitchie Reservoir where he used to court his wife.22 He was posthumously awarded the rank of major-general by the Chinese Nationalist government in 1946.

Lim Bo Seng's wife Gan Choo Neo on the far right in black during his funeral service at Macritchie Reservoir. (Image from the Tham Sien Yen Collection courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore)

Lim Bo Seng's wife Gan Choo Neo on the far right in black during his funeral service at Macritchie Reservoir. (Image from the Tham Sien Yen Collection courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore)

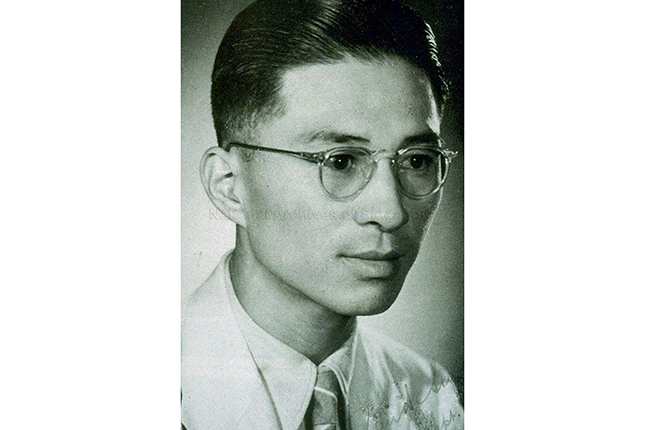

On the 10th anniversary of his death, a memorial built in his honour was unveiled at Esplanade Park. It is the only World War II memorial in Singapore dedicated to an individual. It was gazetted a national monument in 2010 alongside two other structures in the park.

In 2016, Lim’s personal diary which he left behind for his heartbroken wife, resurfaced. One entry reads: “You must not grieve for me. On the other hand, you should take pride in my sacrifice and devote yourself to the upbringing of the children. Tell them what happened to me and direct them along my footsteps.”

Lim Bo Seng’s grave at Macritchie Reservoir (c1946–1959. Image from the Than Sien Yen Collection, National Archives of Singapore.)

Lim Bo Seng’s grave at Macritchie Reservoir (c1946–1959. Image from the Than Sien Yen Collection, National Archives of Singapore.)

Lim Bo Seng’s 50th anniversary memorial ceremony at the Esplanade Park (c1994. Image from the National Archives of Singapore.)

Lim Bo Seng’s 50th anniversary memorial ceremony at the Esplanade Park (c1994. Image from the National Archives of Singapore.)