More than a year into work as a trainee teacher in his hometown of Kajang in Selangor, Malaysia, 18-year-old Adnan Saidi made the life-changing decision to switch careers by joining a military unit specially established for Malays.

The year was 1933 and the unit, which came to be known as the Malay Regiment, had been set up by the British to provide employment opportunities for young Malay men2. Its initial recruitment drive attracted 1,000 candidates of whom 25 were selected.3

Adnan proved to be the Regiment’s most outstanding enlistee, picking up its best recruit award in 1934.4 Along the way, he became a company officer, and was selected to march in a parade in London to honour King George VI’s ascension to the throne.

In 1939, as a brutal war unfolded in Europe, the Regiment began ramping up training exercises. Two years later, amid the rumblings of an impending war in the Far East, Adnan took up a post in Singapore, bringing along his pregnant wife, Sophia Pakih Muda, a teacher by vocation, and two sons. They lived in a house off Pasir Panjang designated for Malay Regiment officers.5

Men of the Malay Regiment training before the war. (Source: Imperial War Museum (FE414)

Men of the Malay Regiment training before the war. (Source: Imperial War Museum (FE414)

This arrangement, however, was short-lived. As air raids increased in frequency, Adnan sent his children and wife home to Selangor by train. They said their goodbyes at Tanjong Pagar Railway Station, with the boys kissing their father’s hand.6 It was the last they would see of each other. According to the recollections of older son Mokhtar, Adnan told them to take care of themselves and be good. “I didn’t know it would be the last time I would see my father,” Mokhtar is recorded as having said. “I was only three years old, but I [can] still remember his face.”7

Lt Adnan Saidi. (Image from the National Archives Singapore)

Lt Adnan Saidi. (Image from the National Archives Singapore)

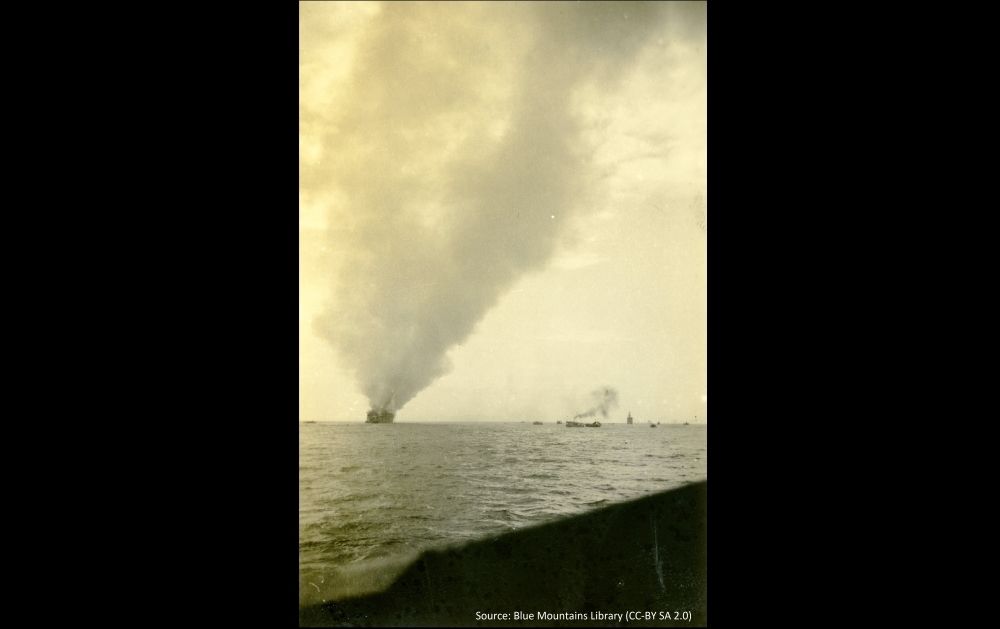

On 8 December 1941, about an hour before the notorious Japanese attack of Pearl Harbour on the other side of the world, General Tomoyuki Yamashita’s men began their invasion of Southeast Asia via the coast of a sleepy fishing village in Kota Bharu, northern Malaya.8 Battle-hardened Japanese troops, commandeering stolen bicycles, made their way on bicycles and motor vehicles into Singapore through the western flank of the Malay Peninsula.9 From 8 to 15 February 1942, the army stunned and overwhelmed Singapore’s defences.

One of the fiercest battles leading up to the fall of Singapore took place at Pasir Panjang Ridge which comprised key military installations such as the British Military Hospital, as well as ammunition and supply depots.

The Japanese had spent the morning of 13 February 1942 inundating the Malay Regiment held area with gunfire and bombs.10 Together with his men, Adnan, a company officer of the 7th Platoon in C Company, was tasked with holding down the fort. Positioned along Reformatory Road11, they were successful in keeping the Japanese’s 18th Division at bay.12

By midnight, Adnan’s company was instructed to regroup at Opium Hill.13 There, Adnan ordered his men to place sandbags around the site to buy themselves time.14 By early afternoon on 14 February, rather desperate members of the Japanese Imperial Army spotting turbans, tried to sneak onto the hill disguised as Sikh members of the British Indian Army. Their attempt to gain ground was foiled by Adnan and 2nd Lieutenant Abbas bin Abdul Manan who noticed they were marching in formations of four instead of three.15 Adnan ordered his men to fire at them. In all, 22 enemy soldiers were killed leading to their momentary retreat.

Two hours later, the Japanese returned with a vengeance. Thousands of soldiers equipped with ample fire power swarmed the site. Despite the heavy shelling, the company held on. When their bullets ran out, they charged at the Japanese, fighting them with only their bayonets and their bare hands.16

The Japanese then had survivors like the badly wounded Adnan executed. Placed in a gunny sack, he was hung upside down from a cherry tree and ruthlessly stabbed to death.17

That was not the end of it. Thirsty for blood, the enemy forces sought out Adnan’s family. To protect themselves, they rid their home of his belongings.

Wrecked by the news of her husband’s death, Adnan’s wife was said to have clammed up whenever her children asked her about him.

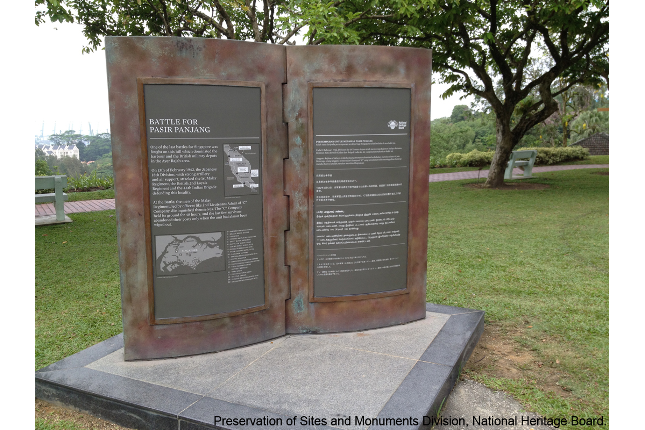

For his valour, the British awarded Adnan posthumous campaign medals.18 In Singapore, Adnan and his men are remembered at a museum called Reflections at Bukit Chandu which opened in 2002. The pièce de résistance at the museum, which reopened in 2021 after a revamp, is a rare and moving clip of Adnan training his troops. It is also at this very site that his values, including his motto, “biar putih tulang, jangan putih mata” (better to die than to live in shame in Malay) live on.

Reflections at Bukit Chandu is an interpretative centre near the Pasir Panjang battle site. (Source: National Heritage Board)

Reflections at Bukit Chandu is an interpretative centre near the Pasir Panjang battle site. (Source: National Heritage Board)