Text by Priscilla Chua

Image courtesy of National Archives of Singapore & National Museum of Singapore

Be Muse Volume 5 Issue 3 - Jul to Sep 2012

"... [W]e cannot depend on other people -- white man, black man, yellow man, whoever it might be -- to look after us; we must look after ourselves. You see, this is our country and we've got to rule ourselves."

- Gerald De Cruz, Organising Secretary of the Malayan Democratic Union (MDU),

Singapore's First Political Party Formed in 1945, in an Oral History Interview, September 1981

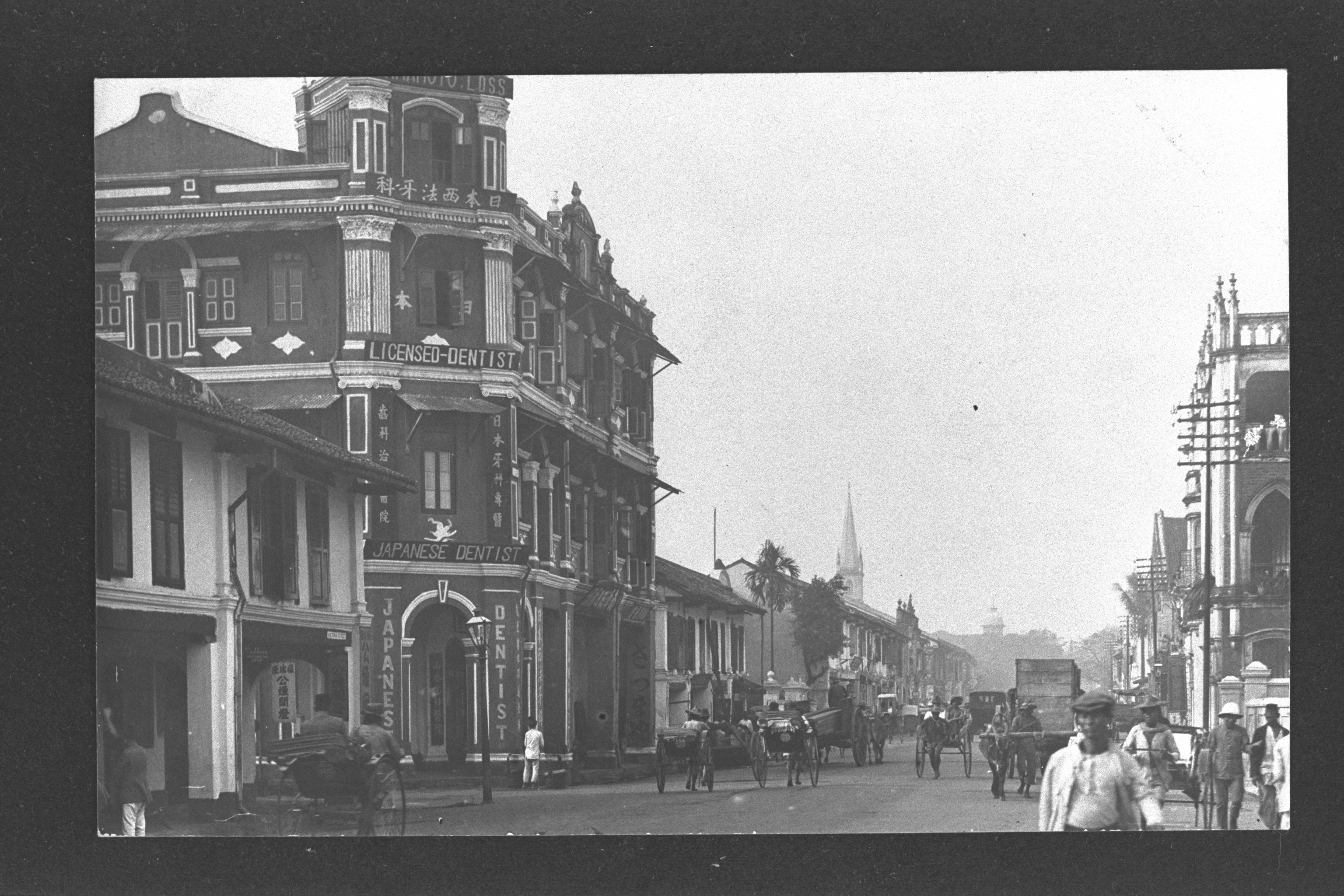

In sharing the political vision he once held for post-war Singapore, Gerald De Cruz captured the prevailing mood among an emerging class of young leaders who were determined to rid Singapore of colonial rule after the British returned at the end of the Japanese Occupation. This marked the awakening of a political consciousness among the masses in Singapore that led to the determined struggle for decolonization and self-rule -- the part of the national narrative most Singaporeans today are familiar with. Lesser known perhaps, but equally important to Singapore's post-war history, were the men-on-the-street whose lives and stories during this period played a part in shaping Singapore's quest to build a national identity as it journeyed towards nationhood.

A collaboration between the National Archives of Singapore and the National Museum of Singapore, 45-65: Liberation, Unrest... a New Nation traced Singapore's post-war history from 1945 to 1965 through six different themes. Using selected artefacts and a range of archival materials such as photographs, oral history interviews, as well as historical documents and footage, 45-65 provided an objective perspective of everyday life in Singapore in the two decades leading up to independence. Just as it illustrated the hardships and challenges faced by the people of Singapore during this tumultuous period, the exhibition offered a glimpse of the cultural dynamism that was prevalent then, thus giving Singaporeans and other visitors today an opportunity to look at how the nation was formed.

Theme 1: Post-war Singapore

Although there was widespread jubilation following the Japanese surrender in 1945, the sense of triumph was soon replaced by a sobering atmosphere as Singapore's immediate post-war years were marked by pressing social and welfare needs. Living conditions were abysmal as the problems of overcrowding continued after the war, forcing families to live in crammed and filthy slums and squatters that had poor ventilation and lacked proper sanitation. Severe shortages of food and healthcare plagued the population, which was also threatened by outbreaks of fire and diseases due to the poor living conditions and overcrowded situation.

Source: National Museum of Singapore.

Yet, in spite of these challenges, this period saw the brewing of an early national consciousness, shaped by the voluntary spirit of locals who rallied to provide welfare support on the ground for a common social cause. The Social Welfare Department (SWD), for example, started a chain of popular "People's Kitchen" in 1946 that offered affordable but nutritious meals to the needy.

Source: National Archives of Singapore.

A similar programme, the Children's Feeding Scheme, was established in 1947, where the SWD supplied free meals to malnourished children. In the face of urgent healthcare needs, and as the colonial administration attempted to curb the spread of diseases such as tuberculosis, cholera and small pox, volunteers also offered their help in providing free healthcare services including mass immunisations and x-ray screenings for the people.

Source: Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts.

Theme II: Stirrings of Discomfort

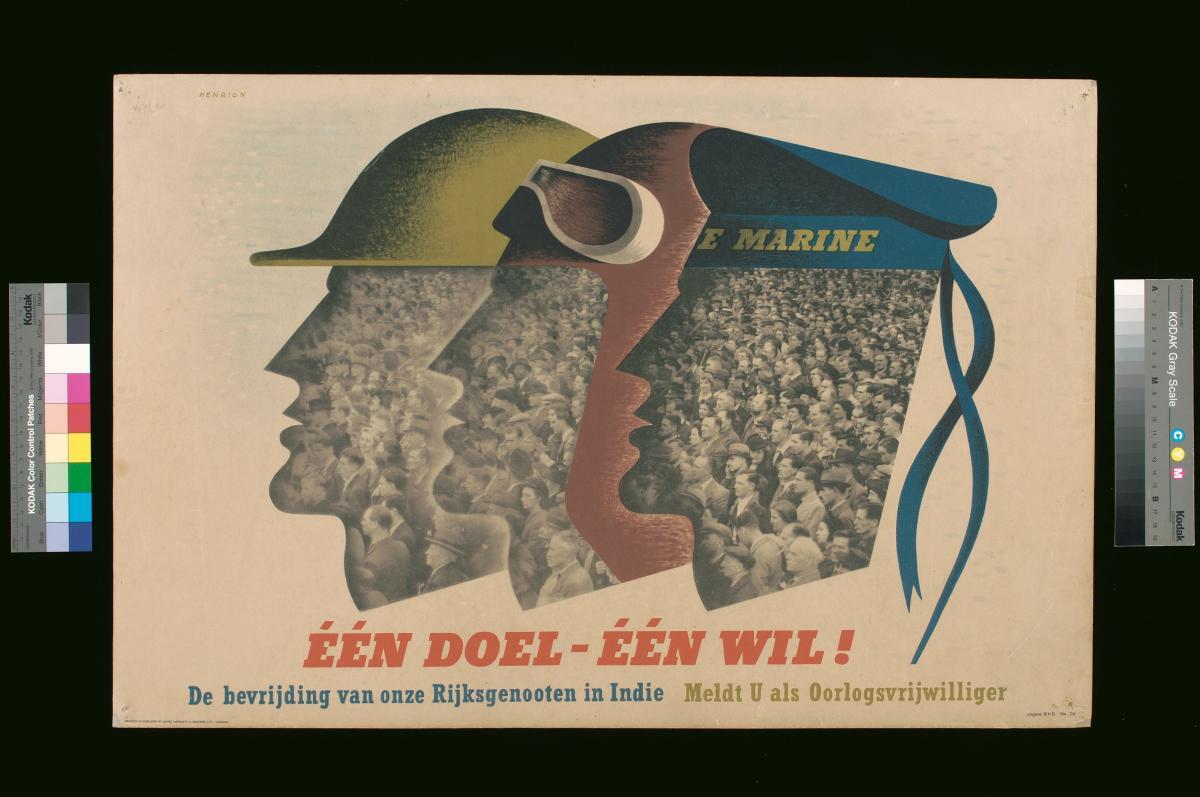

With the image of the all-powerful Western imperialists shattered in World War Two, the widespread social and welfare problems in post-war Singapore soon became sources of discontent that fuelled the spread of political agitation against the colonial government. Different groups within the local population tapped on the ongoing issues of food shortages, unemployment and poor living conditions, many workers participated in strikes instigated by the communist-influenced trade unions, as illustrated by the Hock Lee Bus riots in 1955.

Trade union activism at the that time also saw active participation by students from Chinese-medium schools, whose grievances against the colonial government centred on the relative lack of job opportunities and government aid compared to students from other language-medium schools. Prior to the Hock Lee Bus riots - during which they, too, joined the pickets - the Chinese middle school1 students had organized their own demonstrations to protest against the National Service Ordinance which took effect in 1954, seeing military conscription as a form of colonial oppression that would disrupt their studies.

Source: National Museum of Singapore.

Apart from labour and student riots, communal tensions and inter-ethnic conflict were other causes of violent unrests in the 1950s and 1960s. The Maria Hertogh riots in 1950 and the communal clashes that broke out during Prophet Muhammad's birthday celebrations in 1964 are stark reminders of a turbulent period in Singapore's history.

Theme III: Political Awakening

As the process of decolonization spread across Asia after World War Two, calls for self-government in Singapore gained momentum amid post-war uncertainties and instability. Young, educated members of a disaffected class began to organise themselves, coming together to discuss the shortcomings of the government and plan their course of action, with the ultimate goal for Singapore to break away from colonial rule. It was under such a climate of political awakening that Singapore's constitutional development got underway, as the British took cautious steps to introduce greater local participation in government elections from 1948 to 1959.

Source: Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts.

The breakthrough came after the Rendel Commission of 1953 increased electoral powers, which led to David Marshall becoming Singapore's first Chief Minister of 1955. This was followed by three rounds of constitutional talks with the British to negotiate self-government for Singapore, culminating in the country's first election for a fully-elected Legislative Assembly in 1959. The 1959 General Election was won by the People's Action Party (PAP), and Lee Kuan Yew was sworn in as the first Prime Minister of Singapore.

Theme IV: Towards Nation-building

One of the tasks the PAP embarked on after winning the 1959 General Election was to carry out the social transformation it had promised the people, as the government looked to laying the grounds for building the nation. This included kick-starting Singapore's industrial development, and improving workers' welfare, the healthcare system, housing, education and transport. Dr Goh Keng Swee, then Minister for Finance, called for the formation of the Singapore Economic Development Board (EDB) in 1961 to super the country's economic growth through industrialisation and investment promotion, driven by the priority to provide enough jobs for the people given the massive unemployment at that time.

Source: Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts.

Equal impetus was given to resolving Singapore's housing problems, with the Housing and Development Board (HDB) set up in 1960 to build mass public housing to ease the overcrowding situation.

Source: Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts.

Primary healthcare was also made more accessible to the people of Singapore as hospitals were modernised and mobile clinics were started, while health education and mass campaigns against diseases were launched. Reforms were implemented in the classrooms, too, as the education system was streamlined and improved to cater to the differing needs of the people.

At the same time, the PAP leaders recognised the importance of developing a sense of identity among the people, which they believed was tied to creating a Malayan culture in Singapore. Led by then Minister for Culture S Rajaratnam, the government sought to foster a multicultural and multiracial Malaya identity through the Aneka Ragam Rakyat (People's Cultural Concerts), a series of outdoor traditional shows organized to foster better understanding among the different ethnic groups. The National Loyalty Week was also held in 1959 to introduce national symbols including the state flag and national anthem to the people, which the government hoped would encourage a sense of loyalty among the people to the new nation.

Theme V: Cultural Life

Diverse cultural activities were already taking place on the ground at the time the government started to introduce initiatives and programmes aimed at promotion a sense of common Malayan identity among the people. While the PAP had created the People's Association (PA) to cultivate racial harmony and social cohesion among the population via recreational activities in community centres, such communal interactions were also playing out in public spaces including the three "World" amusement parks2, cinemas, and the Singapore Badminton Hall. Scenes of people from different ethnic backgrounds mingling with one another were common at these venues, as they came together to enjoy boxing matches, cultural dances, movies and sports.

Source: Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts.

Theme VI: Merger and Separation

When Singapore attained self-government in 1959, it symbolised the culmination of a momentous period of political awakening that had begun in the aftermath of the Japanese Occupation in 1945. As the desire of the people to manage their own affairs grew, Singapore's Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew was convinced that complete independence could only be achieved through merger with the Federation of Malaya. This would quell the mounting threat of communism in Singapore, and at the same time secure the country's economic future as Malaya would provide a hinterland and common market for Singapore's manufactured goods.

However, Federation Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman did not share the same vision. He viewed the merger with Singapore's predominantly Chinese population as a threat to the privileged position of the Malays in Malaya, not to mention the threat of communism spreading to Malaya. In Singapore, the political party Barisan Sosialis - founded by left-wing members of the PAP who were expelled from the party in 1961 - also resisted the idea of a merger, fearing that their democratic rights and personal freedom would be curtailed.

Singapore, however, did become a part of the Federation in September 1963, after the Tunku finally proposed the creation of Malaysia following the fears that a pro-communist government might take over in Singapore after the PAP's defeat in the 1961 by-election in Hong Lim.

It was a union fraught with tension. The Sukarno government of Indonesia was against the merger, viewing it as a neo-colonial conspiracy by the British, which led Indonesia on an armed campaigned against Malay during a period known as Konfrontasi (Confrontation) from 1963 to 1965. Relations between the governments of Singapore and Malaysia did not improve after the merger, with one of the thorns being the PAP's decision to contest the 1964 General Election in Malaysia, which the Malaysian government interpreted as a challenge to their political power. Social tensions were also heightened during the racial riots in 1964 between the Chinese and Malays in Singapore, during which 22 people were killed and 461 injured. Furthermore, merger with Malaysia did not produce the expected economic deliverance for Singapore, as the Malaysian common market proved to be a pipe dream. It soon became clear that these irreparable differences made disengagement inevitable. On 9 August 1965, Singapore separated from Malaysia and became an independent and sovereign state.

Source: Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts.

A New Chapter

"The misfortunes that befell Singapore in the first decade of her existence, from a self-governing state to a full independent republic, are forgotten by observers who believe ours has been a smooth and easy transition to self-sustaining growth. The truth is quite the reverse..."

- Dr Goh Keng Swee, A Socialist Economy That Works (1976).

The status Singapore enjoys today as an independent nation state, together with its social and economic stability, were built on the foundations laid during the difficult post-war years. From political strife to economic uncertainty and social unrest, the challenges Singapore faced from 1945 to 1965 had shaped its formative years as a fledging nation in its quest to build a national identity and secure independence.

Through this exhibition, visitors were able to gain an insight into the daily lives of the people during these two decades, a time when bread and butter issues - food shortages, housing and healthcare woes - were the main concerns of families in Singapore. At the same time, Singaporeans today had the opportunity to understand how these 20 years had set in motion the nation-building process and played a part in moulding the Singapore we know now.

Priscilla Chua is Assistant Curator, National Museum of Singapore.

1 The equivalent of today’s secondary schools and junior colleges.

2 Gay World (Happy World), Great World and New World.