Connecting coasts

Hoping to better connect the island of Singapore with peninsular Malaya, a decision was made to build a railway in the days of empire.2

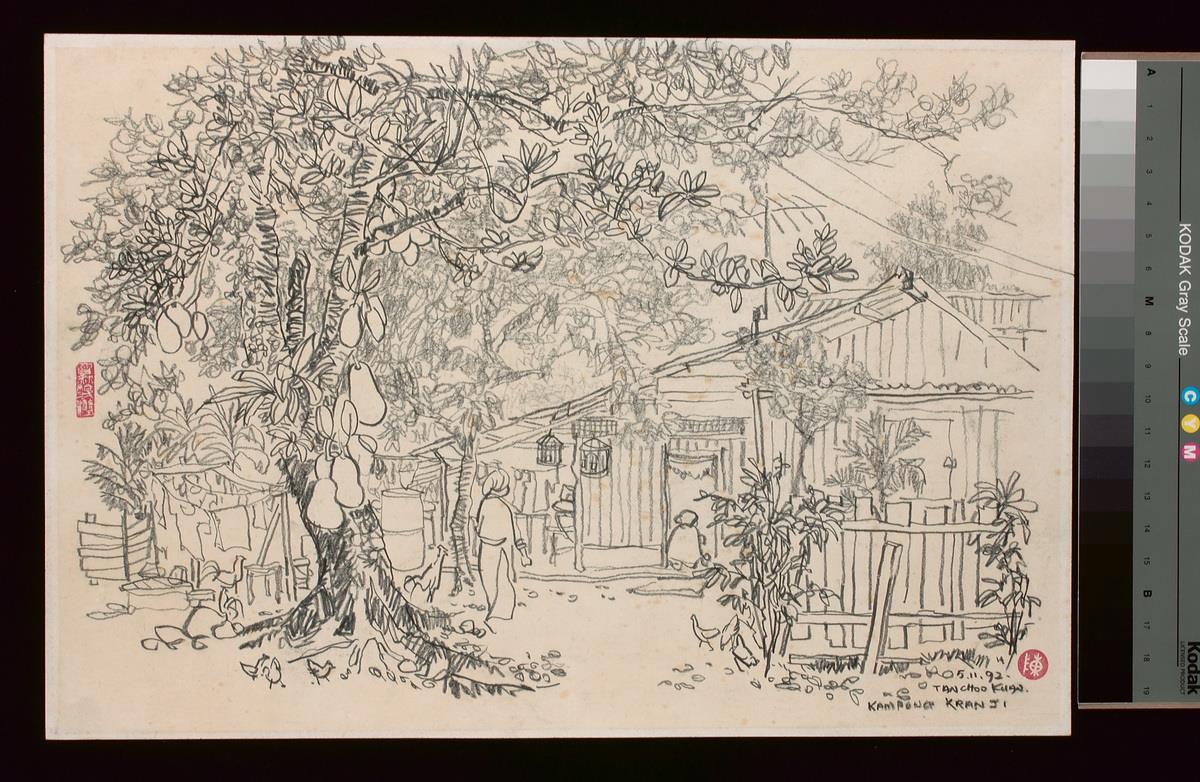

To kick things off, Singapore needed better connectivity within its shores. Up till then, its sole train track had been a five kilometre line plying between Telok Ayer and the harbour at Tanjong Pagar.3 The Singapore-Kranji line was thus built at the turn of the 20th century. It ran from Tank Road to Woodlands by 1903, with an extension to the wharves in Pasir Panjang completed in 1906.4

The Senandung Sutera 24 passenger train in the Kranji wooded area between the crossings of Sungei Kadut and Kranji in 2011. (Darren Soh, Collection of the National Museum of Singapore)

The Senandung Sutera 24 passenger train in the Kranji wooded area between the crossings of Sungei Kadut and Kranji in 2011. (Darren Soh, Collection of the National Museum of Singapore)

Both Malaya and Singapore were eventually connected by land bridge in 1923 via the Causeway. The Singapore end of the bridge was built in nearby Woodlands, along the same shoreline as Sungei Kranji (the Kranji river).5 The entire project, which cost about 17 million Straits dollars, facilitated the flow of tin and rubber from Malaya for further distribution afield.6

The Johor-Singapore Causeway, c.1970s. Collection of the National Museum of Singapore

The Johor-Singapore Causeway, c.1970s. Collection of the National Museum of Singapore

Unfortunately, both the Causeway and Kranji were targeted by the Japanese during World War II as troops charged down from Malaya to invade Singapore.

A weak link7

In a desperate attempt to keep the Japanese at bay, the British blew up part of the Causeway on 31 January 1942. A four-kilometre stretch of land between Sungei Kranji and the Causeway, where the 27th Australian Brigade was stationed, was now in the crosshairs.

On 9 February 1942, Japanese Imperial Guards infiltrating the area met with heavy resistance — their invasion further waylaid by an inferno burning through the Straits and Kranji coastline. The guards suffered heavy losses. Demoralised, they considered aborting the mission.

Unfortunately, critical errors on the part of the Allies led to the complete abandonment of the Kranji-Jurong line, allowing the Japanese to establish strategic footholds. This was all the momentum the Japanese needed to make their advance deeper into the city of Singapore. Singapore fell within a week.

War memorials

After the Kranji Beach landings, Lieutenant General Nishimura Takuma of the Japanese Imperial Guard took over the Kranji Army Barracks — a military base built in the 1930s which has since been levelled.8 The Japanese used it as a prisoner-of-war camp during the early days of Occupation. A small cemetery, started by prisoners, was sited on its grounds.9

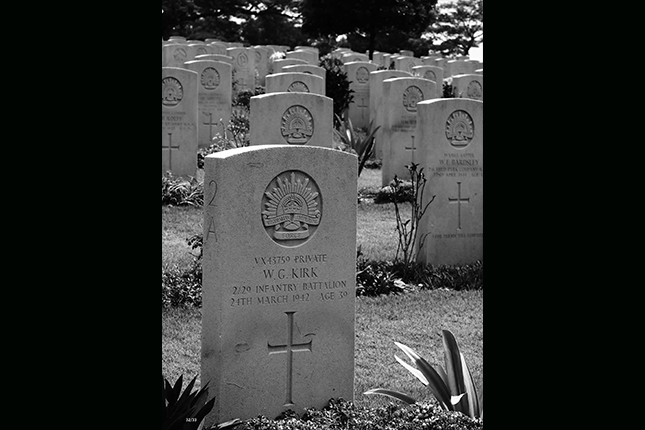

Perhaps in honour of the fierce resistance put up in the area, or the fact that prisoners-of-war had already sown the seeds for a war cemetery, it was decided, following the conclusion of the war, that Kranji would serve as the final resting place for Commonwealth soldiers who died as a result of World War II.10

Built and maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, the cemetery was designed by Colin St Clair Oakes, an architect with the Imperial War Graves Commission. Reflecting a modernist sensibility, the site offers a view of the Straits of Johor and is home to several memorials, the largest being the Singapore Memorial which has been etched with the names of 24,346 men who died in unmarked, unknown graves.

More than 4,400 white gravestones in neat rows also line the serene, well-manicured site.

The Kranji War Memorial was designed to resemble an aeroplane.11 c. 1970s-1980s. (Collection of the National Museum of Singapore)

The Kranji War Memorial was designed to resemble an aeroplane.11 c. 1970s-1980s. (Collection of the National Museum of Singapore)

The Kranji War Memorial from another angle, c. 1970s. (Collection of the National Museum of Singapore)

The Kranji War Memorial from another angle, c. 1970s. (Collection of the National Museum of Singapore)

The Kranji Military Cemetery, a non-world war site of more than 1,400 burials, as well as the Singapore State Cemetery are also housed in this area.