By Kevin Khoo, Assistant Archivist

National Archives of Singapore

Images: National Archives of Singapore

BeMuse Volume 3 Issue 3 - Jul to Sep 2010

The passing of Dr Goh Keng Swee (1918–2010), who laid the foundation stones of Singapore’s economy and defence forces, has left the nation without one of its most well-respected citizens.

The National Archives of Singapore (NAS) wishes to remember and honour Dr Goh for his instrumental role in establishing the Oral History Centre within NAS in 1979. In the words of Mr Kwa Chong Guan, Chairman of the NAS Board:

"We salute and remember Dr Goh for his foresight in establishing an Oral History Centre within the National Archives of Singapore. With his support and guidance the establishment has grown to become the premier Oral History Centre in the region. We are delighted to have had the honour of interviewing Dr Goh in 1980 and look forward to releasing the interview for public consultation, in honour of Dr Goh, and to help a new generation of Singaporeans understand Dr Goh better. (May 2010)"

Apart from his oral history interview, Dr Goh’s memory has been preserved in a rich collection of oral history interviews, speeches, photographs and video recordings possessed by the National Archives of Singapore (NAS). NAS holds over 4,000 photographs of Dr Goh, 700 video clips and some 350 transcripts of public speeches of Dr Goh. These materials are available to the general public for viewing.

Dr Goh was among the most important members of Singapore’s founding generation of leaders. He played a critical role as Minister of Finance in the crucial early years from 1959-65 and from 1967-70 laying the groundwork for Singapore’s subsequent economic development. Though on hindsight Singapore’s economy could appear to follow a clear progressive path, at that time, the task to build an economy was fraught with grave uncertainty, as Dr Goh said in this 1969 speech:

"When my [PAP] government first assumed office on June 3rd 1959..... businessmen and industrialists, far from hailing this event as a happy augury for the future, felt for the most part that the end of the world was around the corner. The stock market collapsed and there was a flight of capital out of Singapore. Several people fled the country. [But] In a short space of ten years, we brought about a transformation of the business climate."1

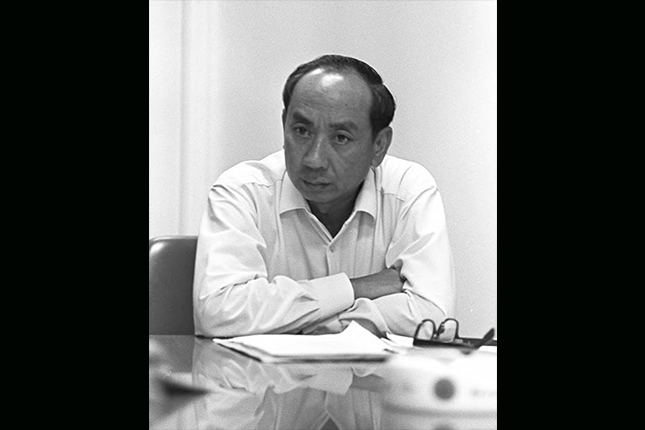

A portrait of Dr Goh, taken during a press conference in 1967.

A portrait of Dr Goh, taken during a press conference in 1967.

Source: Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts (MICA)

Among Dr Goh’s many achievements in helping to bring about this transformation was his role in establishing the Economic Development Board (EDB) in 1961, the Jurong Industrial Estate in 1962 (which he promoted in spite of severe public criticism, though it turned out to be the right move) and the Development Bank of Singapore (DBS) in 1968. These institutions have made, and continue to make, vital contributions to Singapore’s economic success.

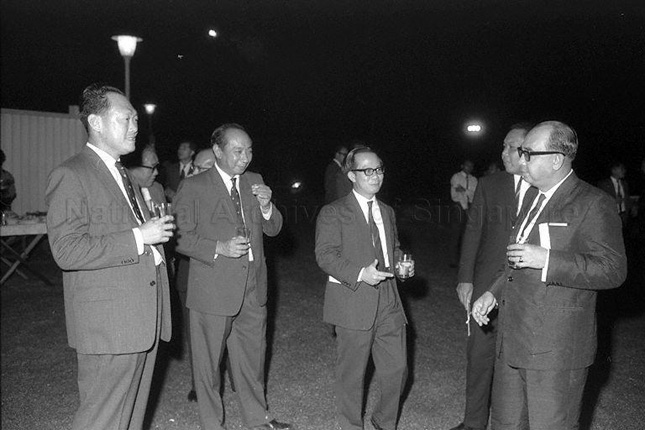

Dr Goh (far left) during a visit to the proposed site for Jurong Industrial Estate, 1960.

Dr Goh (far left) during a visit to the proposed site for Jurong Industrial Estate, 1960.

Source: MICA

The unpromising ground and distance of Jurong from Singapore's town and port led the project's detractors to term it "Goh's Folly". However, the Jurong Industrial Estate turned out to be a great success. By 1976, 650 factories were in operation in Jurong, which became central to independent Singapore's industrialization.

The unpromising ground and distance of Jurong from Singapore's town and port led the project's detractors to term it "Goh's Folly". However, the Jurong Industrial Estate turned out to be a great success. By 1976, 650 factories were in operation in Jurong, which became central to independent Singapore's industrialization.

Source: MICA

Dr Goh launching operations at the National Steel and Iron Mill, the first factory established at the Jurong Industrial Estate, 1962.

Dr Goh launching operations at the National Steel and Iron Mill, the first factory established at the Jurong Industrial Estate, 1962.

Source: MICA

Dr Goh was also responsible for developing the economic strategy that is crucial to explaining Singapore’s economic takeoff. Between 1959 and 1965, he advocated an import-substitution strategy and positioned Singapore as a manufacturing centre supplying the common Malaysian market. Following Singapore’s independence in 1965, Dr Goh realised the futility of keeping to this plan and began promoting an export-oriented developmental strategy. By adopting this export-oriented strategy, he went against influential economic theories circulating in the 1960s and 1970s which asserted that state protectionism and heavy government expenditure was necessary to spur growth in emerging economies.

Dr Goh formulated policies which resulted in Singapore adopting an open economy that encouraged free trade, competition and foreign direct investment by multi-national corporations, while encouraging economic thrift and prudence by the Singapore government and people.2

Dr Goh touring a lubricant blending plant established by Shell at Woodlands in 1963.

Dr Goh touring a lubricant blending plant established by Shell at Woodlands in 1963.

Source: MICA

Dr Goh touring the newly opened factory facilities of Avimo, a British weapons manufacturer, at Jurong Industrial Estate, 1975.

Dr Goh touring the newly opened factory facilities of Avimo, a British weapons manufacturer, at Jurong Industrial Estate, 1975.

Source: MICA

Dr Goh was also convinced that successful economic development depended on the determination, initiative, enterprise and self-reliance of a people and that good government should encourage these qualities. He outlined these convictions in a speech to the Chinese Chamber of Commerce in 1969:

"We in Singapore believe in hard work. We believe that enterprise should be rewarded and not penalised. We believe that we must adjust ourselves to changing situations. We believe in seizing economic opportunities and not let them go past us. Finally, we believe in self-reliance.....These are human qualities that have helped to transform an island-swamp into a thriving metropolis. They are the traditional virtues of Singaporeans and so long as we retain these virtues, we can face the future with confidence."2

Dr Goh’s convictions were proved correct and his thought remains a cornerstone of Singapore’s economic policy.

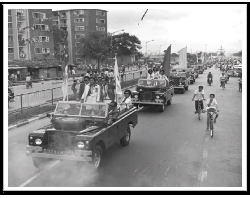

Following Singapore’s separation from Malaysia in August 1965, Dr Goh handed the Ministry of Finance over to his successor Mr Lim Kim San and took up the position of Minister of Defence. As Minister of Defence, Dr Goh was tasked to secure Singapore’s national borders from both internal and external threats. A government gazette released in October 1965 stated that his field of responsibility included “Security, Law and Order, Defence, National Service...People’s Association, Vigilante Corps”.4

Dr Goh visiting Singapore Vigilante Corps trainees at the Mandai training area, 1966.

Dr Goh visiting Singapore Vigilante Corps trainees at the Mandai training area, 1966.

Source: MICA

Dr Goh’s most immediate and important task as Defence Minister was to build a credible Singapore armed forces, literally from scratch, in double quick time. Dr Goh was convinced that a strong Singapore army was necessary to secure the country’s independence:

"British military protection today has made quite a number of our citizens complacent about the need to conduct our own defence preparations. These people assume that this protection will be permanent. I regard it as the height of folly to plan our future on this assumption and, indeed, the only rational basis on which we, as an independent country, can plan its future is on the opposite assumption....Nobody, neither we nor the British can say when this will be....[but] whatever the time may be, it would be useless then to think about building up our defence forces."5

Dr Goh succeeded in this daunting challenge, and in the process laid the foundations of one of the most important and successful Singapore state institutions in a mere six years. Many ideas and institutions on which the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) is built were put in place during Dr Goh’s tenure, for instance a conscript army and compulsory national service for young men.6 He believed that Singapore citizens should participate directly as soldiers in their country’s defence to reinforce their sense of responsibility to the national community and to strengthen their bonds with one another as countrymen. Dr Goh thought that this was especially important as Singapore as a new nation populated by migrants of diverse origins and particularistic interests did not possess a strong national consciousness:

"Throughout man’s long history, defence of the community has always been regarded as a noble duty. In the process of integrating loose collections of people into a nation with a strong sense of identity, military service has played a significant role. From the Greek City States of the fifth century B.C. to the twentieth century continental super powers, we have seen how the development of the national consciousness has been so often centred around service in the defence force... In Singapore, we are not yet a close knit community, so many of our people are of recent migrant origin. All this goes towards creating a sense of values which is personal, self-centred with anti-social tendencies where a conflict arises between personal interests and social obligations. These are the values of a rootless parvenu society. We cannot hope to remove them overnight, but in the process of creating a stronger national consciousness among our people, we will find that military service will play an important role.."7

When Dr Goh gave up his defence portfolio in 1979 he left Singapore with we a well-rounded citizen army containing commando units, armoured battalions and an air force8 – the core of a modern army – when previously Singapore had nothing.

Besides defence and economic matters, Dr Goh also made significant contributions to Singapore in the field of education. Between 1979 and 1985 he was put in charge of the Ministry of Education where he introduced important reforms. The influential Goh Report, released in 1979 under Dr Goh’s supervision, examined the challenges facing the education system and detailed recommendations that would profoundly influence its future direction. Notably, the current practice of ‘streaming’ in schools was introduced through the report, with the purpose of helping all students develop their potential more fully, in particular the weaker students.9 As Dr Goh explained:

"Our system of education, lasting twelve years, has been tailored to suit the brightest 12% of students. The inevitable result is high wastage rates in our schools, both primary and secondary. Automatic promotion was practiced in primary and secondary schools up to 1975 and 1977 respectively. This means that as the slow learners moved from lower to higher classes, they understood less and less of what was being taught. Automatic promotion for Primary and Secondary schools was abolished in 1976 and 1978 respectively and retentions enforced on a large scale. This did not produce the results hoped for. Retention inflicts a psychological trauma on the child and when this is repeated two or three times, it would be an exceptional child who does not lose interest in learning, suffer a loss of self-esteem and self-confidence and develop character defects as a consequence of these. ...We must accept the principle of teaching children of different leaning capacities at different rates. The Report recommends different streams of education to suit the slow, average, above average and outstanding learners."10

Dr Goh was appointed Deputy Prime Minister between 1973 and 1979, and from 1980 to 1985 he was made First Deputy Prime Minister, the position from which he retired from public life in 1985.

A portrait of Dr Goh taken in 1984, when he was Singapore's First Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Education.

A portrait of Dr Goh taken in 1984, when he was Singapore's First Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Education.

Source: MICA

Between 1980 and 1985, he was made Chairman of the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), where he spearheaded major organisational and professional improvements. He also came up with the idea in 1981 that Singapore’s national reserves should be managed by a specialised and professional investment management body that led to the formation of Singapore’s Government Investment Corporation (GIC) in which he served as Deputy Chairman between 1981 and 1994.11

Dr Goh in his later years, in his capacity as Deputy Chairman of Singapore's Government Investment Corporation, 1986.

Dr Goh in his later years, in his capacity as Deputy Chairman of Singapore's Government Investment Corporation, 1986.

Source: MICA

Apart from these achievements, Dr Goh was responsible for initiating or founding a diverse mix of other Singapore institutions, reflecting his remarkably broad range of interests. He championed the establishment of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (setup in 1968), the Jurong Bird Park and the Singapore Zoological Gardens (opened in 1971 and 1973 respectively), and the Singapore Symphony Orchestra (setup in 1978). He conceived the idea of transforming the island of Pulau Blakang Mati, which was renamed ‘Sentosa’ in 1968, from a military base into a tourist and leisure resort – an idea which has come to full cycle with the opening of the Sentosa Integrated Resorts in 2010. He also laid the groundwork for the creation of the Singapore Totalisator Board which was established in 1988.12 Following his retirement, the government of the People’s Republic of China sought out Dr Goh’s expertise and appointed him as its economic adviser on coastal development and tourism in 1985. Dr Goh was the first foreigner to be appointed to such a role – a testament to the international recognition he had garnered for his accomplishments.

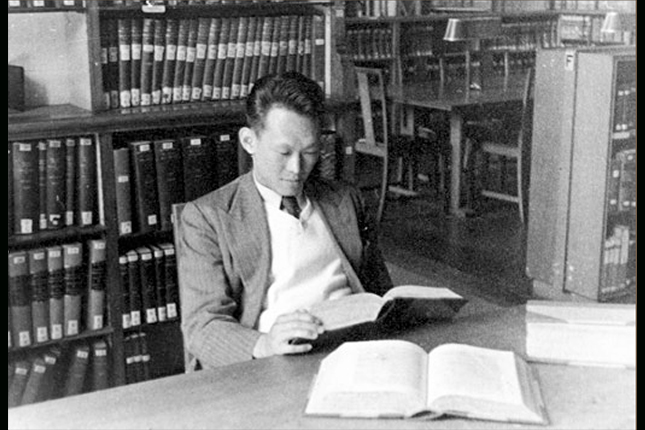

Dr Goh was not only an exceptional Minister. He was a humble and humane person, compassionate for the needs of the less fortunate and deeply interested in social issues. He had in fact started his career as a social researcher at the Social Welfare Department (SWD), which he had chosen to join at the end of the Japanese Occupation in 1945, although the SWD was then a small organisation with little prestige in the civil service. As a young officer in the SWD he played a central role in organising the People’s Kitchens during the British Military Administration (1945- 46). The People’s Kitchens provided very low-cost but nutritious meals which ensured that fewer people went hungry during those difficult years.

Though a relatively junior officer at the time, his keenly analytical mind and wry wit were already evident. This is a passage taken from the preface of a Report on Urban Incomes and Housing which Dr Goh prepared in 1956 when he was Assistant Director of Social Welfare (Social Research) at the SWD:

"I should like to make clear at the beginning the essentially limited scope of the work. Those looking for a penetrating analysis of Singapore’s social problems, covering all aspects in one broad and majestic sweep will look here in vain. This study does not go further than describing some of the things which a team of investigators discovered and reported in the course of five months of field work. Further, it is in the nature of sample surveys to be primarily concerned with the numerical estimation of quantities and relations between quantities....the task of presenting and explaining figures, even when successfully accomplished, does not result in the production of exciting literature. There is, further a class of people to be considered who, doubtless as a result of their early experience in mathematics in school, recoil with horror when confronted by a row of figures. I have great sympathy for such people and have reduced the use of figures in the text of the report to a minimum...I have tried, I hope successfully, to resist the temptation of speculating outside the range of the Survey evidence. Those with fewer inhibitions than myself are welcome to try their hand at this game."13

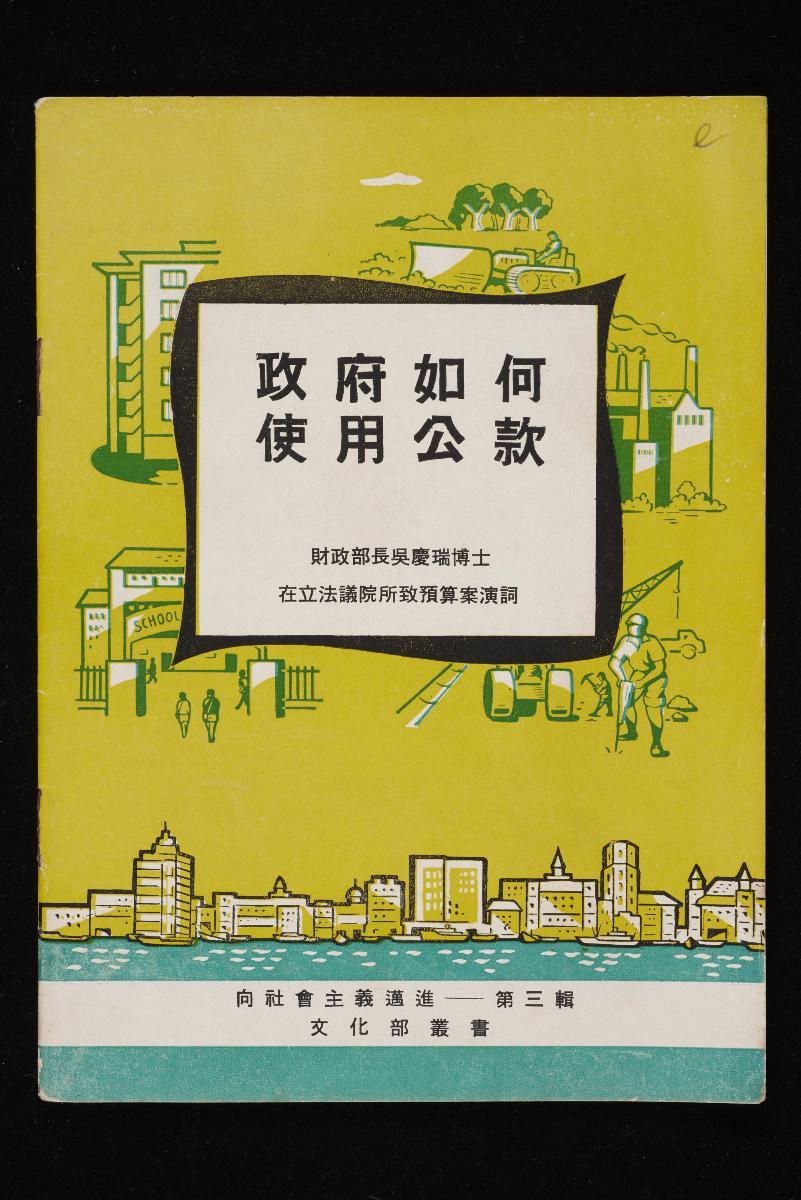

The cover of the Urban Incomes and Housing Report prepared by Dr Goh as a young Assistant Director at the SWD, published in 1956.

The cover of the Urban Incomes and Housing Report prepared by Dr Goh as a young Assistant Director at the SWD, published in 1956.

Source: National Archives of Singapore

To gather fresh data for this report, Dr Goh and his researchers personally interviewed the head of each of the 6,804 households sampled.14 Dr Goh’s method, which stressed detailed field work, gave him and his team a first-hand feel of the ground which led to new insight into the issues studied. As Ms Tan Siok Sun, his daughter-in-law and biographer wrote, “GKS and his researchers ate with the trishaw drivers who they discovered rented not rooms, but beds in the Chinatown area. He learnt that a single bed would be shared by two ‘tenants’, one doing the day shift and the other the night shift”.15

Despite the high office to which he rose and his exceptional talents, Dr Goh always remained a man of simple needs, lived a simple and frugal existence, and was ever ready to humble himself to relate with and aid his fellow men. His wife Dr Phua Swee Liang recalled,

"In his dealings with people, Keng Swee makes no distinction between race, religion, gender, wealth, or power provided they are genuine and decent. Regardless of how simple a view or need might be, he would lend a ear if it is expressed honestly and truthfully. His compassion and thoughtfulness for the common man have always moved and touched me...He has always led a simple and frugal life whether in his official capacity or in private life... Whenever he was warded in hospital, he would tear each tissue paper he wanted to use carefully into halves. He would then put one half back into the box for future use and use the other half. He would often chide me for being a wastrel when he saw that I used the whole sheet and added, ‘its taxpayer’s money’...[but] when the Dover Road Hospice asked for a donation of S$5,000 to purchase an electronic wheelchair for a patient, he wrote the cheque without a second thought."16

His daughter-in-law, Ms Tan Siok Sun also recalled,

"Many who worked with him {Dr Goh} feared him, even those with high intellect and who were clearly competent in their respective fields. His reputation preceded him and followed him to the various ministries that he was put in charge of. Yet these same people respected his towering intellect and the common refrain was that he was a great mentor, and a remarkably patient teacher."17

His outstanding human qualities won him the esteem of even his political adversaries, like the late David Marshall, the famous lawyer, first Chief Minister of Singapore, and critic of the Singapore government. Marshall paid this warm tribute to Dr Goh in an Oral History Interview he conducted with the National Archives of Singapore in 1984:

"Keng Swee was ....a man of ‘sea-green’ integrity, a man of personal charm and warmth if you got close to him, very humble. Genuinely, no showmanship about it, genuinely humble....he speaks to the high as well as to the low....with the same approach. He had an extraordinary....total freedom from arrogance, from superiority, from any inferiority; he just was....a natural human being. And to me, a perfect human being.....it’s so much part of the air he breathes....to serve his country and his fellow human beings. And never a lie from him, never any malice from him...always treating me with courtesy and consideration. Never because I was a political opponent, treated me with ....unpleasant [ness]....never at all."18