MUSESG Volume 16 Issue 2 - July 2023

Text by Angela Sim, Heritage Researcher

Read the full MUSE SG Vol 16, Issue 2

Image above: Performers of the traditional Hakka qilin dance demonstrating the Sitting Horse (四平马; si ping ma) stance. Courtesy of Edmund Lau, Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore

According to popular lore, the birth of Confucius (551–479 BCE), one of China’s greatest sages, was foretold by an omen that took the form of a mythical horned creature. This hooved beast is believed to have appeared to the mother of Confucius and prophesied the greatness of the child who was to be born.

In his adulthood, Confucius himself chanced upon the same creature when it was captured in a royal hunt. After the encounter, the sage predicted the end of his life; true to his word, he passed away three years later. What is the story behind this sacred chimera that foretold the birth and passing of this famed sage and is today revered by the Chinese as an auspicious symbol?

This beast is the qilin (麒麟), one of the four divine creatures in Chinese mythology alongside the turtle, phoenix and dragon. Legend has it that the qilin made its first appearance in the courtyard of the deity Huangdi (Yellow Emperor) in 2697 BCE.1

Myriad Versions of the ‘Chinese Unicorn'

Like many mythological beasts, there is not one single, absolute description of the qilin. It has been depicted in diverse ways, depending on the source.2 The scholar, Jing Fang (77–37 BCE), described the qilin as approximately two metres tall and having five colours, including a yellow underbelly.3 Another contemporary, Liu Xiang (77–6 BCE), wrote in his book Shuoyuan (說苑) that the qilin does not live in herds, does not travel, never falls into snares, is aware of its surroundings and seeks solace on flat ground. The qilin is said to be restrained, humble and unobtrusive.4

More than a millennium later, the Neo-Confucianist scholar, Zhu Xi (1130–1200), described the creature as possessing the tail of an ox and the body and hooves of a deer. Apparently, when it walks, it glides over grass, careful not to trample on any insects in its path.5

The depiction of the qilin as a unicorn only began in the Qing dynasty (1644–1912). In the Ming era (1368–1644), it had been portrayed with scales covering its deerlike body.6 Though sometimes referred to in English sources as a ‘Chinese unicorn’, the qilin may be depicted with one, two or more horns. Contemporary depictions of the qilin usually feature it with one curved horn at the top of its head and two or more smaller horns down its back.

Possessing the head of a dragon, the tail of a Buddhist guardian lion and four goatlike hooves, the qilin exudes a menacing aura and a commanding presence. Yet, despite its aggressive demeanour, there is a gentleness to the creature. The qilin is also believed to be an excellent judge of character, being associated with righteousness, benevolence and virtue.7

Qilin: Here, There and Everywhere

In Ming-dynasty China (1368–1644), nobility and the emperor’s sons-in-law wore badges depicting revered, mythical creatures such as the qilin. These badges were also awarded to those who had proven themselves with meritorious or special service. During the reign of Qing Emperor Kangxi (r. 1661–1722), the qilin became the emblem of first-rank military officers.8 Each mythical animal of the military rank insignia is said to symbolise the degree of the wearer’s courage.9

Besides China, the qilin is also mentioned in ancient Korean legends. King Chumo,10 the founding monarch of the kingdom of Goguryeo (37 BCE–668 CE; comprising today’s North Korea, northeastern China as well as parts of South Korea and Russia), has been described as riding the qilin during his reign.11 More recently in 2012, North Korea claimed that it had discovered the cave—Kiringul (Kirin’s Grotto)—that was the supposed lair of the qilin that King Chumo rode.12

Closer to home, the qilin can be seen on the tok wi, a piece of embroidered fabric that is draped over an ancestral altar in Hokkien and Chinese Peranakan homes. Sacred auspicious animals like the qilin are common imagery depicted on the tok wi. The fabric consists of two main sections: an upper panel and a longer lower panel. The former represents life after death while the latter symbolises life in the physical world.13

Interestingly, the mythical qilin also appears in contemporary popular culture. In the 2022 fantasy film Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore, a qilin assumes the role of leader among wizards. Director David Yates explained the presence of the qilin in his film: “In the wizarding world of the past, the qilin was called upon in elections: all the candidates would line up, and the qilin would approach each candidate, and if it bowed to one, that would influence the people’s choice.”14

Finally, perhaps one of the most widely seen yet also easily missed qilin iconography is found on the logo of the Japanese beer brand, Kirin—the Japanese word for qilin. In Japanese culture, the qilin is known for its ability to bring about happiness, peace and tranquility.15

A tok wi (altar cloth) is a length of fabric that is draped over a Chinese ancestral altar. Sacred creatures such as the qilin (pictured in the centre) are usually depicted in elaborate embroidery. Courtesy of Yuhan Embroidery Studio 裕涵繡莊

A tok wi (altar cloth) is a length of fabric that is draped over a Chinese ancestral altar. Sacred creatures such as the qilin (pictured in the centre) are usually depicted in elaborate embroidery. Courtesy of Yuhan Embroidery Studio 裕涵繡莊

Hakka Qilin Dance in Singapore

Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore is among the country’s foremost qilin dance troupes, 2022. Courtesy of Edmund Lau, Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore.

Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore is among the country’s foremost qilin dance troupes, 2022. Courtesy of Edmund Lau, Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore.

In Singapore, the most significant representation of the qilin can be found in the form of the Hakka qilin dance.16 Accompanied by Chinese percussion instruments, this traditional dance is similar in form to the more common Chinese lion dance, but here the qilin is the star of the show.

The qilin dance is believed to have its roots in the Qianlong period (1735–96) of the Qing dynasty. Historically, the Hakka people subsisted mainly on farming.16 The dance originated as a ritual to cleanse areas where the farmers dwelled and to drive away any evil entities that lurked in the vicinity.

The dance was also performed to invoke clement weather for a good harvest, or to celebrate a bountiful harvest. The Chinese idiom, ‘国泰民 安,风调雨顺’ (peaceful country and favourable weather), is often sewn onto the body of the qilin prop or painted onto the bottom of its head frame.17 It is not uncommon to see Chinese lion dance troupes performing during auspicious occasions such as the Lunar New Year or when seeking good fortune for one’s new business or home in Singapore. However, what is little known is that the qilin ranks above the lion. When a lion or dragon dance troupe encounters a qilin troupe during a performance, the dancers will bow as low as possible as a mark of deference and respect to the qilin.18

The qilin dance used to be de rigueur at Hakka celebrations such as weddings, births, the first-month celebration of a newborn and religious festivals. Today, however, there are very few troupes in Singapore that faithfully and accurately perform this dance due to waning interest as well as the demanding skills required. One such troupe that continues to breathe life into this age-old tradition is Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore (恩隍文化团新加坡), founded in March 2015 by Eugene Wan, who also heads and coaches the troupe.

The qilin in flight pose during a performance, 2022. Courtesy of Edmund Lau, Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore

The qilin in flight pose during a performance, 2022. Courtesy of Edmund Lau, Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore

A Childhood Dream

Eugene Wan’s foray into the qilin dance form began as a childhood dream. In 1984, a four-year-old Wan was entranced by a qilin dance performance televised during a Lunar New Year programme from Hong Kong. Some 15 years later in 1999, Wan embarked on his dance journey with a troupe after commissioning the making of a qilin head.

With a deep desire to learn the finer techniques of this intriguing dance, Wan set out on a mission to find a shifu (master). But this was no easy task: few people in Singapore were skilled in the art form.

Wan’s quest eventually took him to Hong Kong, and in 2015 he met Master Yeung Chun Mo (楊振武; Yang Zhen Wu), the martial arts director of Tsuen Wan North Praying Mantis Gymnasium. Master Yeung specialises in the kung fu style known as Northern Praying Mantis (北螳螂; bei tanglang). He also created his own qilin dance style—the Yang Zhen Wu style—which is known for its exceptionally low stances and fast, powerful movements. Two years after their first encounter, Master Yeung officially took Wan under his wing as a disciple, with Wan becoming the first Singaporean to perform the Yang Zhen Wu qilin dance style.

Master Yeung believes that the qilin is an ascetic that does not kill or hurt living creatures, and is peaceable even while it eliminates evil and harm. Unlike the lion which may come across a snake or a centipede during the dance sequence, the qilin confronts only inanimate objects. While the lion would groom or lick its hooves after a ‘kill’, the qilin does not do that. In the Yang Zhen Wu dance style, the tail of the qilin is not manouvered by the dancer with a string, which is what happens in the lion dance.19

Eugene Wan (right), founder of Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore, with Master Yeung Chun Mo, who taught him the qilin dance form, 2017. Courtesy of Eugene Wan, Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore

Eugene Wan (right), founder of Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore, with Master Yeung Chun Mo, who taught him the qilin dance form, 2017. Courtesy of Eugene Wan, Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore

Dancing to the Percussion Beat

In the qilin dance, movements are accompanied by a percussion ensemble made up of traditional Hakka instruments: a gong (高边锣; gao bian luo), a pair of large cymbals (广钹; guang bo) and a small drum (小战鼓; xiao zhan gu). Together, they create a powerful and hypnotic rhythm. But the heart and soul of the qilin dance are the sound of clashing cymbals, unlike the lion dance which is driven mainly by drums. These cymbals measure 45 centimetres in diameter, much larger than the 30-centimetre cymbals used in the lion dance.

A full set of percussion instruments used in a qilin dance. From left: a gong (高边锣; gao bian luo), a small drum (小战鼓; xiao zhan gu), a pair of large cymbals (广钹; guang bo) and the master’s drum (师公鼓; shi gong gu). Courtesy of Edmund Lau, Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore

A full set of percussion instruments used in a qilin dance. From left: a gong (高边锣; gao bian luo), a small drum (小战鼓; xiao zhan gu), a pair of large cymbals (广钹; guang bo) and the master’s drum (师公鼓; shi gong gu). Courtesy of Edmund Lau, Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore

Sometimes, a special drum known as the shi gong gu (师公鼓; literally ‘master’s drum’) is used during the performance. This drum is believed to contain the energy and essence of all the past shifu (masters). Given its importance, the shi gong gu can only be played by a shifu or someone of an equivalent standing. It is a tough instrument to master, and a high level of skill is required to achieve the precise tone when the drum is struck.

Eugene Wan (pictured paying respects), the founder and coach of Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore, at a performance on Kusu Island, 2022. Courtesy of Edmund Lau, Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore

Eugene Wan (pictured paying respects), the founder and coach of Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore, at a performance on Kusu Island, 2022. Courtesy of Edmund Lau, Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore

Each qilin performance kicks off with five drumbeats from the shi gong gu. This signifies a mark of respect to elders and an invitation for the late masters to bless the performance. Yan Wong Cultural Troupe’s shi gong gu features a talisman that represents the deity qilin tongzi (麒麟 童子), who is the protector of the troupe.

Strength and Grace: Qilin Dance Moves

A qilin performance comprises two dancers: one at the front controlling the head and one behind as the torso. Appearing almost ceaseless and unrelenting in their moves, qilin dancers, driven by the propulsive percussion, leap high into the air, kicking their hooves. The elaborate dance is characterised by sudden bursts of movement and surges of energy. Known for being expressive, the qilin’s gestures connote surprise, wakefulness, strength, attack and suspicion by turns.

Qilin dancers adopt low stances unlike the lion dance, which is marked by more feline movements. The ability of the troupe is measured by how low a stance the sinewy performers can achieve during the performance. Dancers are trained in endurance and depend very much on the strength of their thigh muscles. Another unique characteristic of the dance is the powerful head movements—the left-toright motion of the qilin head represents respect to elders.

The most basic stance in the qilin dance is the Sitting Horse (四平马; si ping ma). The weight of the dancer is centred and evenly distributed, imparting strength and sturdiness as well as stability with each step. The dancer at the front uses both hands to grip the qilin’s head tightly; his elbows, wrists and fingers must be strong and flexible in order to create dynamic movements. The dancer’s elbows are kept within range of the qilin’s head and usually not exposed. Barring certain movements, the head of the qilin cannot be lowered or allowed to fall, and its back must always be parallel to the ground.

The Bowing Horse (弓字马; gong zi ma). Courtesy of Edmund Lau, Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore

The Bowing Horse (弓字马; gong zi ma). Courtesy of Edmund Lau, Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore

Another common stance is the Bowing Horse (弓字马; gong zi ma), a kung fu stance used for low attack or evasion. In this movement, the qilin’s left hooves remain flat on the ground, with both right legs extended, and the dancers’ bodies are turned towards the left to face the front. The trunks of their bodies must be stable, aligned with the centre of gravity. The weight distribution should be 70 percent on the front foot and 30 percent on the rear.

The Cat Stance (吊马; diao ma). Courtesy of Edmund Lau, Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore

The Cat Stance (吊马; diao ma). Courtesy of Edmund Lau, Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore

Also noteworthy is the Cat or Tiger Stance (吊马; diao ma). Here, the dancer’s front leg is lifted, with the rear leg bearing the weight and his body like a coiled spring. The final stance is the Qilin Step (麒麟步; qilin bu)—a gait that represents both offence and defence. In this stance, each dancer’s legs are crossed one over the other. The key to this stance is the coordination of hands and feet as well as a stable gait.

The Qilin Step (麒麟步; qilin bu). Courtesy of Edmund Lau, Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore

The Qilin Step (麒麟步; qilin bu). Courtesy of Edmund Lau, Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore

The Art of Making the Qilin Prop

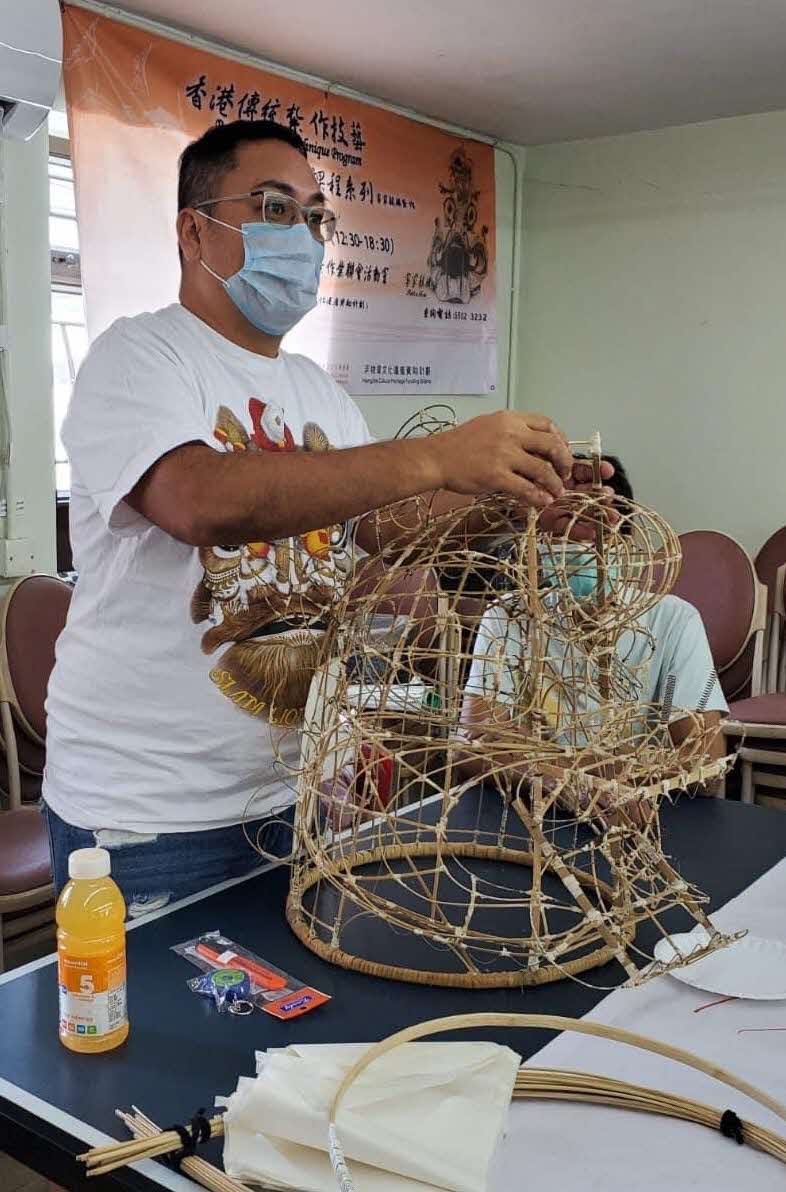

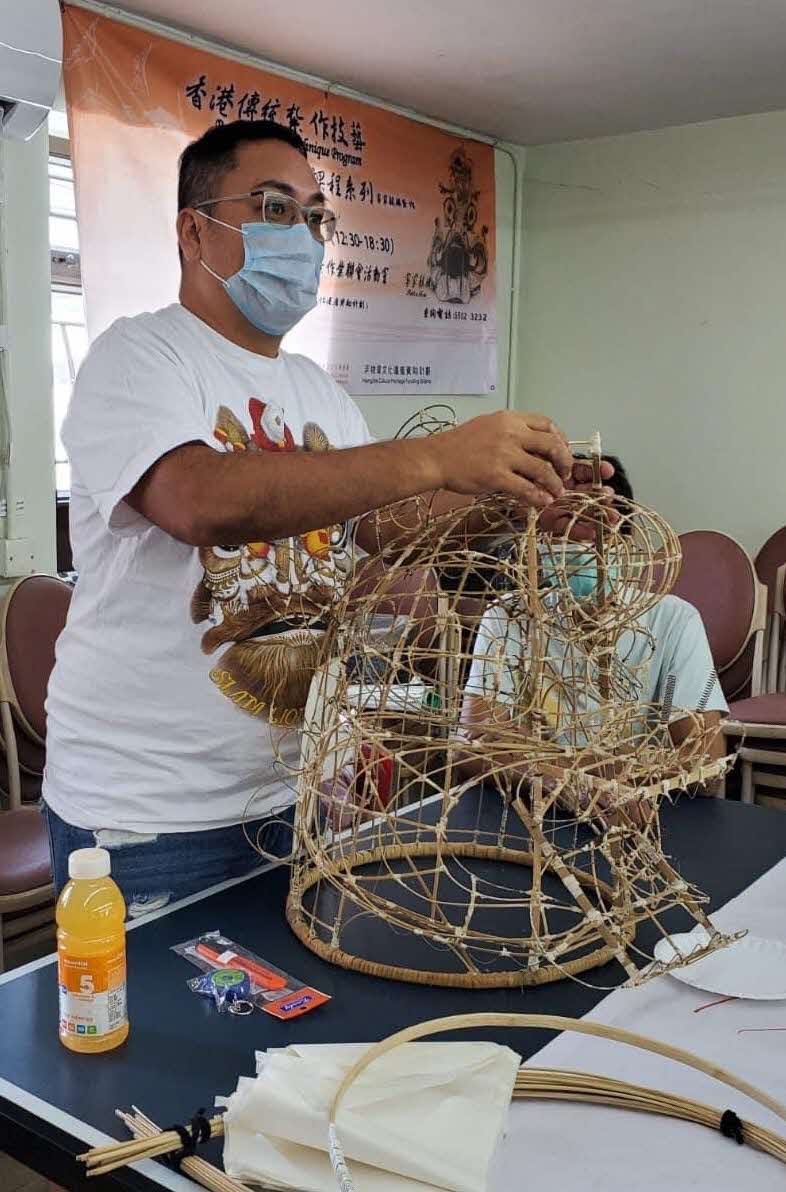

The qilin prop used in the dance is made by a dwindling handful of artisans. The head frame is crafted from bamboo, instead of rattan, for its pliability and strength. As the head frame requires great stability, the bamboo has to be carefully selected. It gives the qilin head its signature asymmetrical shape, while its weight also directly affects the dancers’ movements.

The skill of the craftsmen is reflected in the intricate structure of the head frame, which is constructed with numerous bamboo pieces bound together with strips of paper. When the skeleton is complete, layers of paper are glued on using a homemade paste, while ensuring that all the curved parts such as the horns are smooth and even.

A craftsman demonstrating how the qilin head is crafted from bamboo, 2021. Courtesy of 古洞冒卓祺金龍 麒麟 醒獅 扎作 Kenneth Mo

A craftsman demonstrating how the qilin head is crafted from bamboo, 2021. Courtesy of 古洞冒卓祺金龍 麒麟 醒獅 扎作 Kenneth Mo

When the structure is dry, a white basecoat is painted over before the patterns are drawn in bright colours. Commonly seen auspicious designs include the bamboo, chrysanthemum, plum blossoms and the bottle gourd, which are associated with the qilin’s benevolent character. Other embellishments such as bells, pom poms and rabbit fur are also incorporated at this stage.

Arguably, the most beguiling feature of the qilin’s head is its eyes. Traditionally, these were made from hollowed-out duck eggshells, but due to their fragility, table tennis balls are now used instead. Sometimes, light bulbs that can be lit up are used in place of table tennis balls.20

Other noteworthy features include intricately painted fish scales at the back of the head and on the body, comprising five colours that represent the five directions: north, south, east, west and centre. These are also known as the five celestial marshal camps that ward off plagues, misfortune and demons.

The back of a qilin’s head with scales and a row of smaller horns, in addition to the large horn at the top of the head. Courtesy of Angela Sim

The back of a qilin’s head with scales and a row of smaller horns, in addition to the large horn at the top of the head. Courtesy of Angela Sim

The Future of Qilin Dance in Singapore

Qilin dance was once a hallmark of Hakka culture in Singapore. If not for the few surviving qilin dance troupes in the city-state, this aspect of Hakka culture would have faded into obscurity long ago. The decline of qilin dance can be attributed to diminishing awareness and interest among the Hakka community, especially the younger generations. For older Hakka people, the dance symbolises the embodiment of the spiritual and the ritual. It is a performance that is said to counter evil, purify, renew and bring blessings to the community.

In spite of the waning interest in qilin dance, it is heartening to know that Yan Wong Cultural Troupe Singapore has recently been receiving members as young as nine years old. There is hope yet that the legend and the qilin dance form can continue to be kept alive in the years to come.