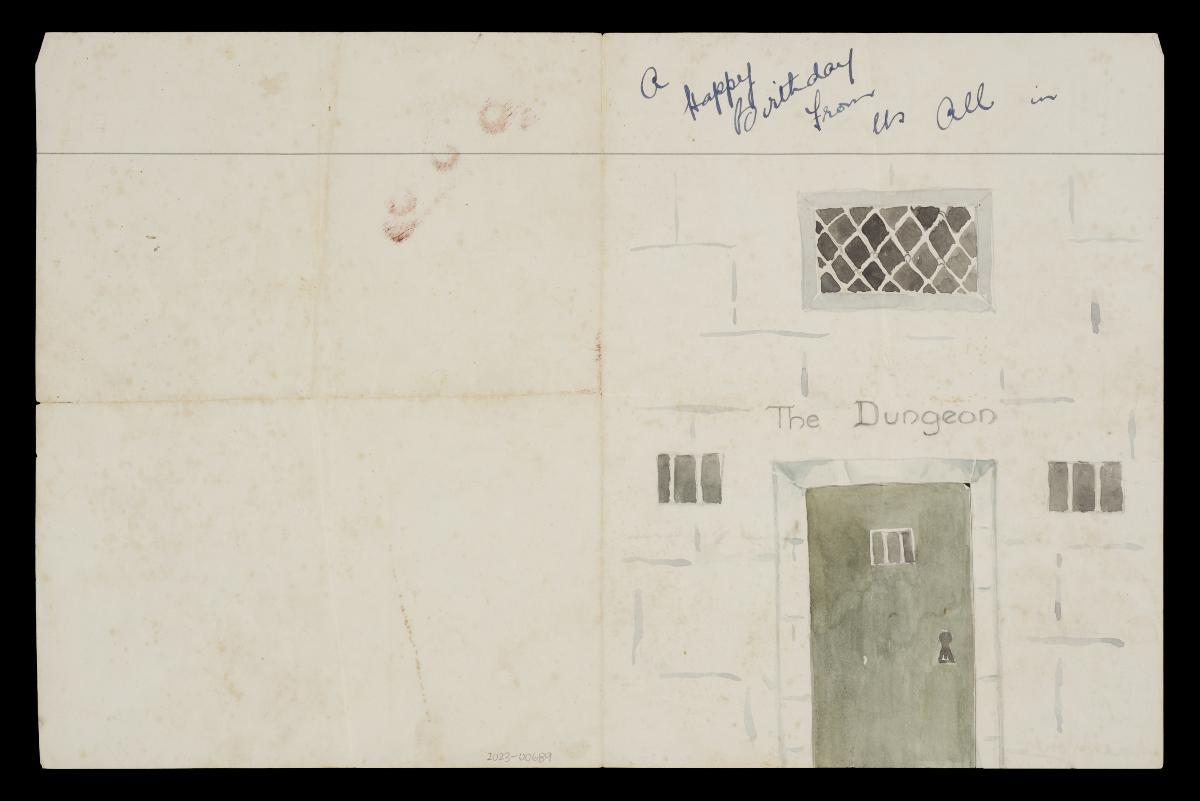

On the face of it, being a prison volunteer does not seem to have anything in common with being a museum guide, but May sees it differently. To her, both have to do with unlocking the prisons of the mind.

Whether it is inmates wanting to lead meaningful lives as free citizens or the man-on-the-street entering a museum to settle a doubt he has about a historical event, the common thread is the need to free the mind from the shackles of bias and misinformation.

“We just keep in our shells. We don’t know things until somebody unlocks them, and you go exploring on your own,” says May.

Inspiring stories

May takes pains to ensure that visitors get the most out of a museum trip. “There are so many things people can do in an hour. But, if they choose to step into a museum, it is my responsibility to offer them a memorable experience. So, I think accuracy of fact, being very comprehensive, engaging them, and bringing artefacts to life are important,” she says.

Having served over a decade as a prison volunteer, May decided to add being a museum guide to her list of volunteer activities. She wanted to balance the sad stories she hears from inmates with stories of hope from Singapore’s history.

Conversations with prison inmates tend to revolve around questions about their personal history including what made them commit a crime and so on, says May. Being a docent, she feels, would put her in touch with the inspiring stories of Singapore’s forefathers who “came here with nothing and worked very hard”. It would also give her a wellspring of anecdotes to use when encouraging others, be they in prison cells or outside seeking a sense of their roots.

So, when May learnt that docents were being recruited for the Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall (SYSNMH), she was thrilled. She enrolled in the docent-training programme run by the Friends of the Museum (FOM). “I thought, well, this is a great chance to get to know the works of this great man, and what better way than to attend a training programme.”

In her own words

The aspects May likes about being a docent are that it enables her to internalise historical information, and share it with museum visitors in her own words. “Although a picture paints a thousand words, it is the docent who brings depth to life,” says May.

Using as an example the bust of Zubir Said on display at the Malay Heritage Centre, May explains that a docent can depict his journey in life by piecing together biographical details of the historical figure.

May points out that without someone fleshing out the details of Zubir’s life—how he left Indonesia for Singapore without his father’s permission so that he could fulfil his dream of becoming a musician, how from a self-taught musician he became a composer with Cathay-Keris Studio, and how he declined payment for writing the music and lyrics of the national anthem Majulah Singapura because the honour of doing it was sufficient reward for him—one would see the sculpture, but miss the man.

“So the ‘picture’ here is Zubir Said, but I want to tell my story of how he became a good composer, and how we have a street named after him —Zubir Said Drive — because he had the drive. It is not Zubir Said Road or Zubir Said Street,” quips May, exercising a little poetic license to inject a bit of fun into history.

Docents are essentially the character of a museum in human form. Aware of the gravity of her responsibility in being the “face” of the cultural institutions she guides at, May continuously updates the information she shares with the public. She has 20 files into which she slots newspaper clippings and other bits of information she comes across pertaining to the artefacts she speaks about during her tours.

“You must like to talk to people and that’s no problem with me,” says May, adding that her experience as a prison volunteer has sharpened her ability to connect with people. Whether they are corporate clients or children, “you must be able to go to their level”.

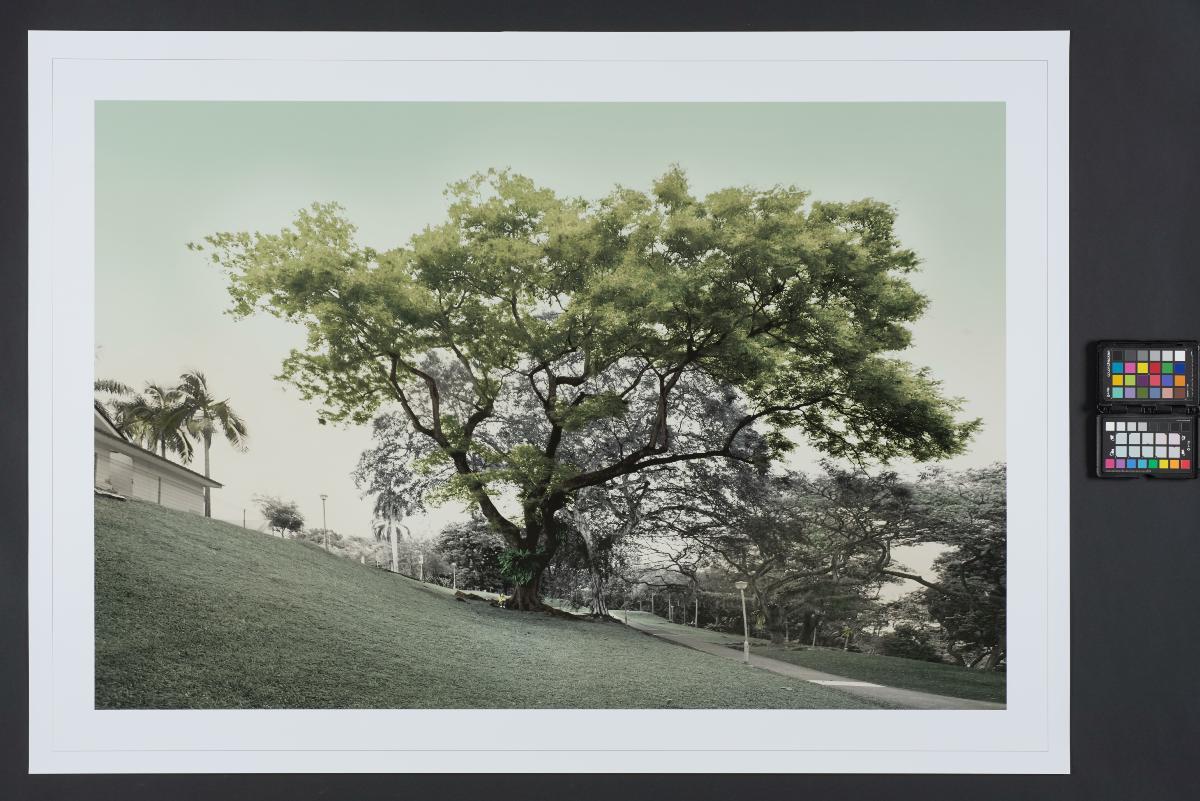

Beyond the museum

It is this talent for reaching out to people that puts a shine on May’s work as a docent. During one of her tours at the Malay Heritage Centre, May overheard a couple of the visitors saying they used to live at the Joo Chiat area in Singapore. After the tour, May told them that Zubir Said used to live there as well. After Zubir retired from Cathay-Keris Studio in 1964, he spent his time teaching music at his home in Joo Chiat Place.

“They were so excited and said, ‘I’m going back to look for it.’ The trip to the museum should not end here. They should be able to do something with the information they have been passed,” says May. “They should explore further, especially during school holidays when they bring their kids along. So, it’s a responsibility that I have passed to parents — to go and explore the neighbourhood with their children.”

By Richard Philip