When she was a young woman, Long Chin Peng had to quit her job as a Chinese teacher. Being a mother of four children, of whom two had special needs, meant she had to spend endless hours feeding them with special bottles, ferrying them to doctors, dentists and speech therapists, and worrying while they recovered from surgeries. She felt that there was absolutely no way she could balance that kind of stress with a full-time job.

Soon enough, her kids grew older and more independent. They began urging her to get out of the house and pick up new hobbies. She still remembers their encouraging words: “Mummy, you should go and do something you like.”

By coincidence, the Asian Civilisations Museum (ACM) had just begun a recruitment drive for volunteer Mandarin guides. She found out about it from an advertisement in the LianheZaobao, while she was eating dim sum with friends at Chinatown’s Yum Cha Restaurant. All three of them signed up, but only she was called back for an interview.

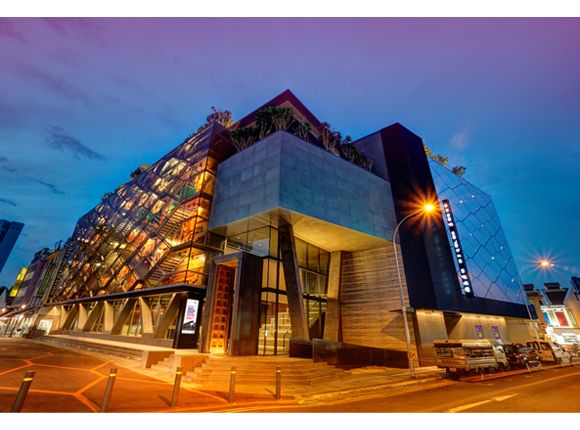

That was back in 2003. Today, the 49-year-old Chin Peng is one of the most active and respected volunteer guides among the Mandarin Docents. She leads tours not only at the ACM, but also at the National Museum of Singapore, the Peranakan Museum, the Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall, the Malay Heritage Centre, and the Indian Heritage Centre.

The Peranakan Museum is especially dear to her heart as her aunt is a Nyonya, and Chin Peng did her thesis at Peking University on Peranakan culture. As a member of the Museum Volunteers group at the Peranakan Museum, she guides visitors in Mandarin as well as in English.

On top of all this, Chin Peng also volunteers at institutions that are not operated by the National Heritage Board. These include the National Gallery, the Art Science Museum, the National Library, Nanyang Technological University’s Chinese Heritage Centre, the Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations, the Kong Chow Wui Koon, the Istana, and the newly-opened Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre. In short, she has gone from being a full-time mother to a full-time museum volunteer.

Patriotic duty

What drives Chin Peng to do so much of this work? In part, it is a sense of patriotic duty. “I try and contribute back to society,” she says. “I love my country. I love my country’s history, so I want to carry it onwards.” Whatever exhibition she is in, whether it is about the Silk Road or Southeast Asian artists, she takes care to explain how it relates to Singapore’s multicultural identity.

However, she has also developed a special bond with the museum staff and volunteers. That makes her feel like they are part of her own family. “You walk into the museum and it’s like going back home. Sometimes, when we don’t have enough visitors, we just walk through and talk to the security staff. They take care of us very well.”

Over the years, she has learned to tailor her tours to different audiences. When she is with kids in the Peranakan Museum, she takes them to the play area near the wedding galleries, or points out where they can stamp their tickets. When she is with elderly visitors, she asks them about their own heritage and their memories of the past.

VIPs require special treatment. Because they are often on tight schedules, she often has to give them a 20-minute whirlwind tour of an exhibition’s star pieces. As she talks, she monitors their faces closely for signs of boredom, so she can lengthen or shorten her explanations accordingly.

The next generation

Recently, Chin Peng has also been training kids to be Mandarin guides themselves. She does twelve-hour workshops with students, teaching them to create tours of the Peranakan Museum, Asian Civilisations Museum, and Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall.

This is difficult for many of them, especially when they have limited vocabulary. When they are asked to write about the artefacts, their descriptions are often full of English words, and hanyu pinyin (Romanised Chinese). But, with a little coaching, Chin Peng builds up their confidence and soon has them speaking fluently in their mother tongue. A few weeks later, their fellow students arrive on a field trip, and the kids are able to present a complete tour of the galleries to their friends.

On occasion, Chin Peng has even had family members join her as volunteers. In 2012, her son Lukas had finished his polytechnic studies, and was waiting to enlist for National Service. He and his cousin decided to help her out with the many activities that the Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall had planned for its anniversary. While she led VIPs through the galleries, they worked as receptionists and picked up guests at the airport. This gave them a new sense of appreciation for all the work that goes into sustaining our heritage.

These days, Chin Peng finds that she is often involved in recruitment drives for new volunteers—something she never dreamt she would be doing when she first signed up 14 years ago. She is impressed by the calibre of the new docents, who are often highly educated professionals. Notably, many of them are new immigrants from China, with excellent Mandarin skills.

However, what is most important to her is whether a volunteer is truly committed. “I will always ask them, ‘Do you have the passion? And, do you have the time?’ Because if you don’t, then it will be very hard,” she says. “You may have to make sacrifices. You have to really want this.”

Of course, Chin Peng’s own commitment has never been in question. After years of devoting herself to the health and welfare of her family, she is free to share her knowledge about history—an act which truly brings her joy.

By Ng Yi-Sheng