Som Said is Singapore’s most famous Malay dance choreographer, and she cares deeply about heritage. In fact, she has spent over fifty years performing and teaching traditional Malay dance.

However, her love for the past has never stopped her from trying new things. Over the years, she has created many innovative performances, sometimes by borrowing dance techniques from other cultures or by using modern technology.

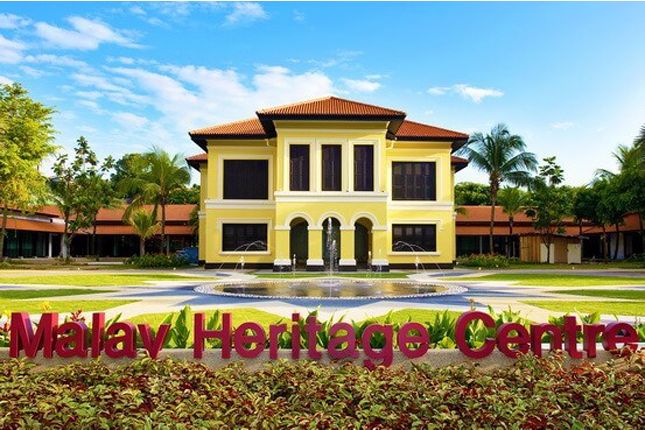

For example, last year, her company staged an event at the Malay Heritage Centre called “Inspirasi 9”. It took place over two nights. On 11 November, dancers mostly performed folk dances, such as masri, joget and zapin. But, on 12 November, they put up contemporary works, interacting with video and live computer animations.

“Tradition is not static,” she explains. “When heritage is passed down from generation to generation, it has to keep moving to stay relevant.”

Growing up with dance

When Madam Som was a little girl in the 1950s, she did not have a dance teacher. Instead, she learned dance by watching movies. She would go to the cinema with her sisters to watch Malay films, then spend hours at home in front of her mirror, trying to imitate them. (She says it was quite similar to how kids today learn dance from YouTube!)

She began teaching her schoolmates the dance routines. By Primary Two, she was already creating dance performances for her school’s Sports Day. Then, while she was in Anderson Secondary School, her friend invited her to join her father’s dance troupe, Sriwana. She began taking part in public performances at the age of 14, in the year 1965.

“Sriwana did folk dance, but we did not emphasise tradition,” Madam Som remembers. “We also did modern dance to pop songs. During that time, people didn’t care about what was traditional and what was modern.”

She was, therefore, able to make some interesting changes to traditional Malay choreography. Some dances had always used items like fans and umbrellas, but she began to feature more unusual props like trays, drums and betel boxes. She also used the dances to tell old Malay legends, such as the tale of how ancient Singapore was attacked by swordfish.

While she still loved the old Malay folk dances, she knew they had originated in Malaysia or Indonesia. She wanted to create new works that reflected her Singaporean surroundings. She found plenty of ideas simply by attending weddings. Each weekend, she carefully observed the movements in the ceremonies and people’s interactions, and incorporated all that into her dances.

Dancing for Singapore

From 1970 onwards, she was also a dancer in the National Dance Company, a new troupe set up by the government that included people trained in Chinese, Malay and Indian dance. The company was trying to create a new dance tradition that would reflect the cultures of all three major races in Singapore.

Madam Som was doubtful about the project. “I wondered, why are we rehearsing so hard? Why do I have to learn Indian dance and Chinese dance? What are we going to present?”

Then, in 1972, the company performed at the Adelaide Festival in Australia. To her surprise, audiences loved the show. This proved that a young, multiracial nation like Singapore could develop a culture of its own. Madam Som was so moved that she later named her son “Adel”, after the festival.

Sadly, the National Dance Company closed down in 1985 due to lack of funds. But, its spirit still lives on in the Singapore Multi-Ethnic Dance Ensemble. This is a multicultural dance troupe for kids, run by Madam Som and her fellow dancers Yan Choong Lian and Neila Sathyalingam.

She trains students in Malay dance, while Madam Yan and Madam Neila train them in Chinese and Indian dance. “Instead of just Malay heritage, this is Singaporean heritage,” she says.

Traditions add to identity

Since 1997, Madam Som has been the Artistic Director of her own company, Sri Warisan. It has been called Singapore’s first professional Malay dance company because it pays its performers a proper salary. (Madam Som had previously earned money by running a bridal boutique, while rehearsing her dances at night.)

The truth is, Sri Warisan focuses on more than just dance. It promotes all kinds of traditional Malay performing arts, including angklung music, bangsawan opera and wayang kulit puppetry. Last year, its dancers participated in festivals in Qatar, Poland and Guam, while its puppeteers travelled to Spain, Russia, Malaysia, Brunei, Myanmar and Vietnam. They also ran arts education programmes in 122 different Singapore schools!

However, now that she is 66 years old, Madam Som rarely dances. She still teaches classes, and serves as a judge for the Singapore Youth Festival. But, she spends most of her time researching the history of Malay dance in Singapore, so that she can write a book about the subject. “It’s a new step for me, to share, to write about why we dance,” she says.

She feels optimistic about the future of Malay dance. Although it has changed in many ways, its foundations are strong, and it remains closely connected to the folk dances she learned as a girl.

In the same way, she believes Singaporeans can move forward while holding on to their “jati diri”, or identity. To her, tradition is not a burden. It is an inspiration.

-by Ng Yi-Sheng

This article first appeared in What's Up, a newspaper that explains current affairs in a way that children find comprehensible and compelling.