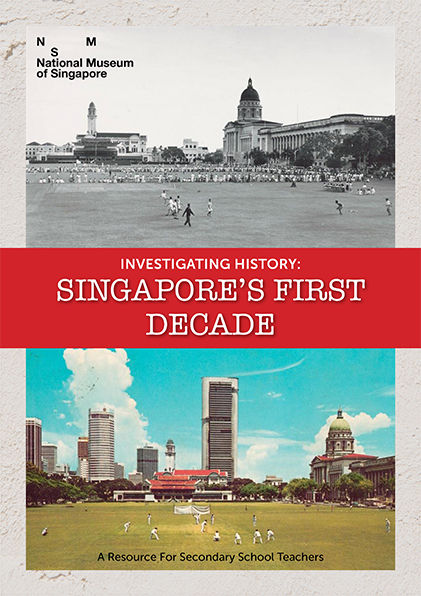

In the early 1980s, the Singapore government was making plans to develop Fort Canning Hill. They wanted to turn it into a centre for entertainment and culture, with an underground car park for 300 vehicles.

But, some employees of the National Museum (present-day National Museum of Singapore) were unsure about this. They knew that there were legends that a palace had stood on the hill in the 14th century. In January 1984, they invited an archaeologist to investigate the site for any traces of Singapore’s ancient past.

The archaeologist’s name was Dr John Miksic. He still remembers the trip vividly. “We had ten days,” he says. “I had three groups of workers: museum staff, hired Indian labourers, and some national servicemen who were being punished. I was not sure what kind of cooperation I was going to get from them, but once I explained what we were doing, they got very interested.”

At first, his team found only the skeleton of a goat, an old British army helmet, and a few bricks from the 19th or 20th century. To make matters worse, it rained heavily. Every day, he would go back to his hotel with his shoes covered in mud.

The team started digging near the Keramat Iskandar Shah, a shrine which is said to mark the tomb of the last king of Singapore. “Suddenly we saw the soil colour change and we started finding different kinds of artefacts,” Dr Miksic says. Among these items were pieces of blue and white Chinese porcelain, made during the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368). This meant that the site dated back to at least the 1300s.

It was a landmark moment. The team had found evidence that a 14th century settlement really had existed on Fort Canning Hill. In response, the government agreed to change its development plans. They knew that the remains of ancient Singapore were far too precious to be disturbed.

Fascination with history

Dr Miksic was born in the USA in 1946. He grew up on a farm in western New York. Sometimes, he would find old Native American stone arrowheads on the ground, which made him wonder about life in the past. This fascination with history led him to become an archaeologist.

Since then, he has carried out digs in many different countries, including Canada, Honduras, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Myanmar and Cambodia. However, most of his work has taken place in Singapore, where he still lives today.

Over the years, he has found some remarkable treasures in our soil. For instance, he uncovered pieces of a Chinese porcelain bowl, which was once used as a compass. Sailors would have filled the bowl with water, and then floated a magnet on the water’s surface. The free-floating magnet would naturally point north. This is the world’s only surviving example of a compass like this.

Another strange artefact is a tiny statue of a headless man on a winged horse. It is made of lead. As far as we know, the metal lead was not used in statues in ancient Southeast Asia. He is still deeply puzzled about how it came to be in Singapore. He thinks it may represent Raja Chulan, an Indian king who was said to be the father of Sang Nila Utama.

As an archaeologist, he does not rely solely on buried objects to get information about the past. He searches for historical documents from all over the world – such as writings by European traders, Chinese explorers and Javanese historians – to build up a picture of what ancient Singapore was like.

Great contributions

“Life in 14th century Singapore was a lot like modern life,” he explains. The population was multiracial, including Malays, Chinese, Indians and Orang Laut. They worked a variety of jobs, such as fishing, winemaking, saltmaking and working with metal. They mostly seem to have lived in a small area, inside a walled city. There would probably have been trees within these walls, meaning that we were already a garden city in ancient times!

The rulers of Singapore had to worry about keeping peace with larger neighbouring kingdoms in Java and Siam, which attacked Singapore on different occasions. The rulers also reached out to China; there are records that they gave gifts of tribute to the Chinese Emperor and commanded their subjects not to attack Chinese traders. However, we mostly enjoyed good trading relations. This may explain why the remains of trade goods from all over Asia have been discovered in our soil.

Clearly, Dr Miksic has made huge contributions to our knowledge of Singapore’s ancient past. Yet, if you ask him what his greatest accomplishment is, he will not talk about his discoveries. Instead, he will describe his work as a teacher. He has trained young Southeast Asians in archaeology so they can learn more about their own cultures.

“One of them is the head of the Anthropology Department of Indonesia,” he says. “One of them just became the Head of the Economic and Social Commission for the AsiaPacific in Bangkok.” His Singaporean students include Goh Geok Yian. She is developing a digital Database for archaeological remains from the Singapore Cricket Club and is also an expert in Burmese history.

Dr Miksic is delighted that more and more Singaporeans are starting to become aware of our ancient past. Not only does this give us a deeper understanding of history; it also gives us a lot of pride as a nation. “We were not just a minor fishing village,” he reminds us. “We were actually an important place.”

-by Ng Yi-Sheng

This article first appeared in What's Up, a newspaper that explains current affairs in a way that children find comprehensible and compelling.