Text by Goh Tiong Ann (Student Contribution)

MuseSG Volume 9 Issue 3 - Jan 2017

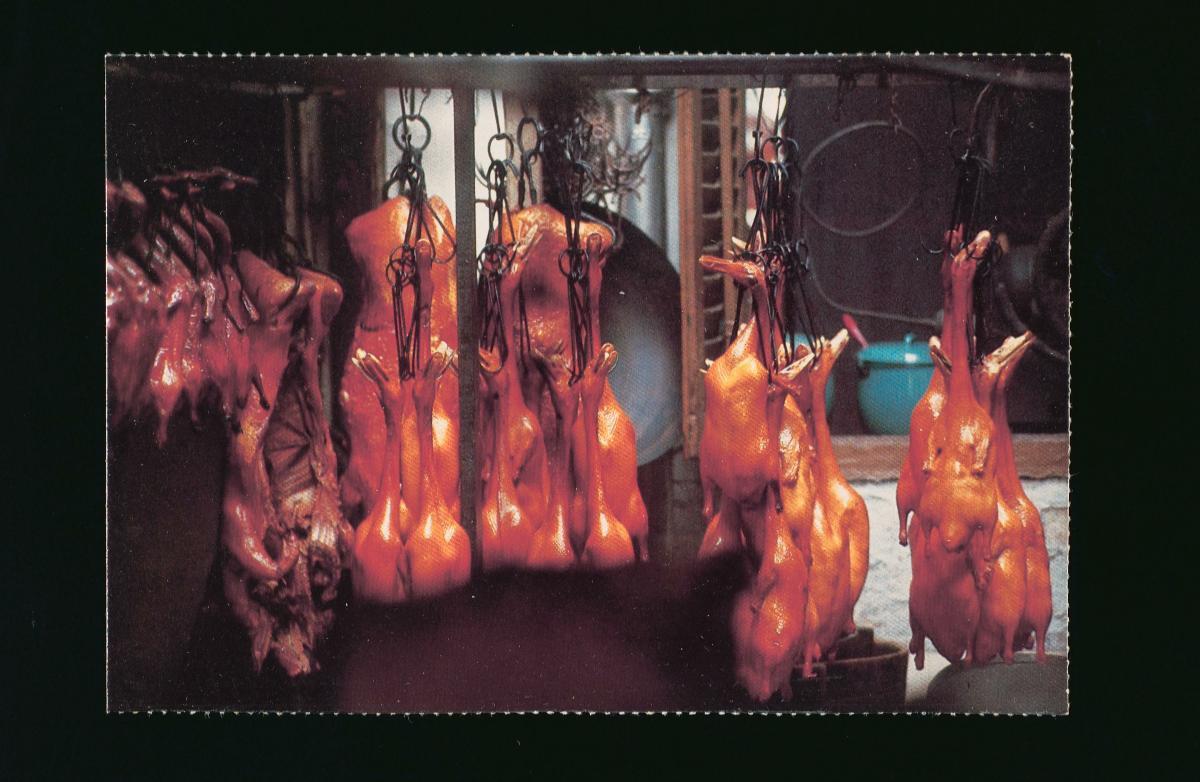

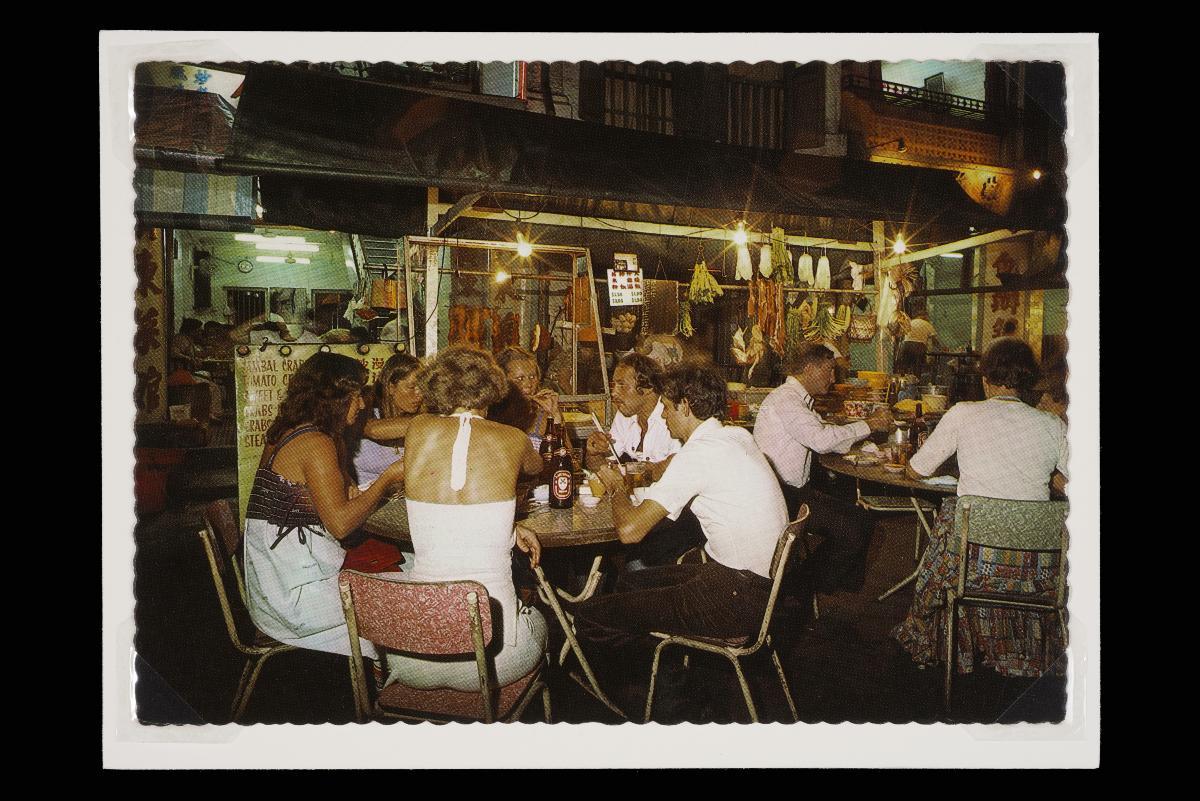

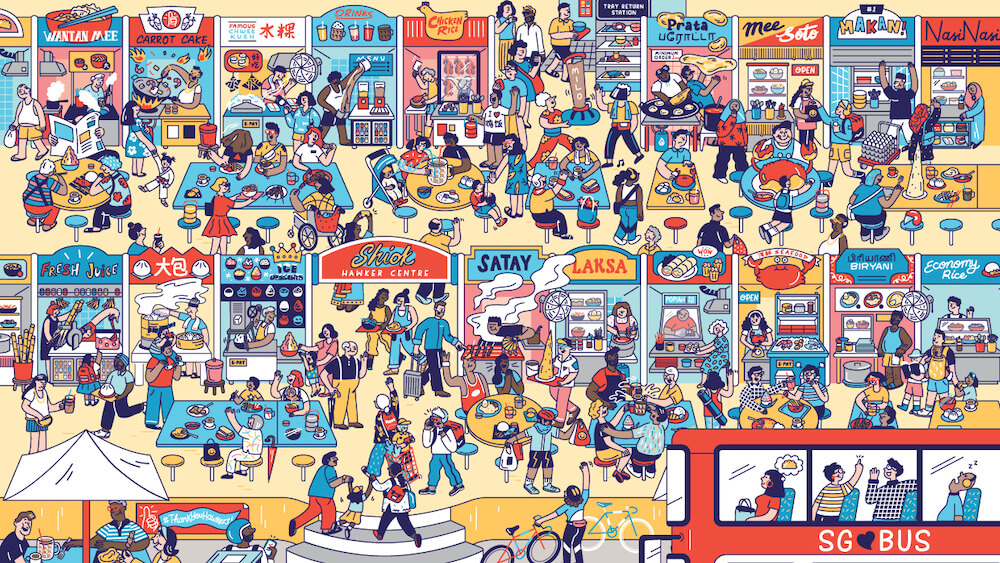

Singaporeans have fond memories of their beloved hawker centres. They bear witness to significant as well as ordinary events such as our first taste of chilli, our birthday celebrations, our breakfast rituals and the constant satisfying of our hunger pangs. Hawker centres allow us to gather and eat at communal tables, savouring and partaking in each other’s food heritage.

It is a place where we build our sense of solidarity as we stand side by side in line for that famous nasi lemak (“coconut milk rice” in Malay) while discussing where the best Indian rojak (“mixture” in Malay) can be found. Hawker centres, however, did not exist in the years before independence in 1965. To examine what precipitated their formation, let’s examine this issue with a view from the top, beginning in 1950 with what the Colonial Government termed as the “Hawker Problem”.

THE HAWKER PROBLEM

In 1950, the Governor of the Crown Colony of Singapore, Sir F. Gimson, established the Hawkers Inquiry Commission to study and recommend solutions for what the government termed as the “Hawker Problem”. According to an article from The Straits Times in November, 1950, hawkers were seen by government officials as “primarily a nuisance to be removed from the streets”, because their unsanitary conditions were contributing to the spread of diseases while their stalls were obstructing cleaners from tidying up the streets during the post-war era.

An earlier attempt in the 1930s to license hawkers was not effective because most hawkers were illiterate and did not understand the requisite hygiene standards to get licensed. The 1950 report reflected that about two-thirds to three-quarters of hawkers were operating illegally without licences. Police constables who were tasked with enforcing hawker licenses were regularly bribed. Frequent police raids carried out on illegal hawkers were also criticised for not only being ineffective at deterring illegal hawking, but also causing unnecessarily painful losses to the poor hawkers. The hawkers received widespread public support because they provided meals at affordable prices. Any attempt at dismantling the hawkers’ livelihood was perceived to be an excessive abuse of colonial authority.

Some solutions were proposed, including making licenses more attractive to hawkers. Another recommendation to place hawkers into approved shelters or markets was deemed ineffective because people would rather eat outdoors where there was better ventilation. Unless there was a provision for the wholesale rebuilding of entire residential estates, there would be no easy solution to the “Hawker Problem”.

POST-INDEPENDENCE: A CHANCE TO REBUILD

The golden opportunity to redevelop large neighbourhoods came after independence in 1965. The Housing and Development Board (HDB) was given the authority to rebuild entire housing estates to accommodate new residents from the old kampongs (“village” in Malay). In order to feed residents from these new neighbourhoods, the Parliament legislated a programme to build hawker centres in conjunction with new housing and industrial estates. From 1971 to 1986, 113 government hawker centres were constructed to house street-side hawkers.

According to Professor Lily Kong, in her 2007 book Singapore Hawker Centres: People, Places, Food, poor hygiene remained an issue despite the new facilities. Hawker centres were dirty as a result of stray animals and rodents eating leftovers from the floors.

Compounding matters, hawkers also carried on their bad habits from their street hawker days, such as smoking while preparing food or handling raw food and money without washing their hands. These conditions provoked urgent action and in the 1980s, the government started enforcing stricter hygiene practices through punitive fines. This was further enhanced in 1987, when a Point Demerits System was put in place. Hawkers who broke hygiene rules were given demerit points and repeated offenders would have their licenses revoked.

Beyond reactionary measures, the Ministry of Environment also instituted pre-emptive solutions to deal with refuse and trash in the hawker centres. Contract cleaners were employed to clear tables of crockery and leftover food quickly. Hawkers also had to undergo an annual inspection and were given a hygiene grade, from A to D, which had to be prominently displayed one their storefronts. A “D” grade would most certainly turn customers away.

The Ministry of Environment also launched a public education campaign, encouraging the public to exercise its consumer power to influence hawkers to maintain hygiene standards through the dissemination of pamphlets, brochures and travelling exhibitions. Then Minister for Environment, Dr Ahmad Mattar, said in 1989 that as long as people continued to patronise eating establishments and hawker stalls of questionable hygienic conditions, Singapore would not be able to weed out irresponsible food handlers.

Government officials recognised the role of hawker centres as more than mere food establishments. In 1977, Mr Chai Chong Yii, then Member of Parliament for Bukit Batok and Senior Minister of State for Education, extolled hawkers to “work in harmony and with the spirit of mutual accommodation”. Hawker centres were places where people from all walks of life could gather to enjoy a wide variety of food options. Their integration with town centres and convenient location next to bus interchanges, ensured that hawker centres remained popular among neighbourhood residents.

NEW HAWKER CENTRES FOR THE NEW MILLENNIUM

Over time, hawker centres were inevitably beginning to show signs of deterioration. A Straits Times report in September 2000 revealed that hawkers wanted better ventilation in hawker centres as it could become very stuffy in the late afternoon after the lunch crowd had left.

As neighbourhoods were starting to get upgraded from the 1990s, the Ministry of Environment took the opportunity in 2001 to launch the Hawker Centres Upgrading Programme. Then Acting Minister for the Environment, Mr Lim Swee Say, told The Straits Times in February of 2001 that as we were upgrading our living environment, it was only appropriate that we also upgraded our eating environment.

Renovated hawker centres were installed with anti-slip floorings, new sewage and water pipes, a reorganised table and stool layout, as well as innovative architectural features to improve ventilation.

The upgrading process involved gathering feedback and suggestions from the public and the hawkers themselves. One major suggestion was to retain the characteristic features of individual hawker centres, such as iconic trees or signboards.

LOOKING BEYOND

In October 2011, the Singapore government announced that it would build 10 more hawker centres, after a hiatus of 26 years, focusing on HDB towns currently facing an under-provision of eating options, subject to land availability. In 2012, the government announced the towns where the 10 new hawker centres will be built. These include the first three new hawker centres in Bukit Panjang, Hougang and Tampines. In March 2015, it was announced that another 10 new hawker centres would be built by 2027.

As many early-generation hawkers began to retire, a group of Singaporeans took it upon themselves to catalogue their valuable history, knowledge and skills for the benefit of future generations. Dr Leslie Tay, a family physician, started his blog ieatishootipost in 2006 to post professionally crafted photos of hawker favourites, helping to chronicle and digitise Singapore’s hawker heritage online. He also interviews venerable store owners, who are always happy to share something witty and memorable, and sometimes drop hints of their secret ingredients.

Hawker centres have withstood the test of time and continue to reinvent and prepare themselves for the future. Even in today’s modern age, the old-school charm of savouring delicious hawker fare in the midst of the clanging of woks and the sizzling hiss of fried garlic is not one that can be easily replaced. Hawker centres have certainly evolved from being a problem in the earlier part of the 20th century to today forming an indelible part of our everyday lives.