Over the centuries, Singapore chalked up a complex history of connections with empires near and far. The inscriptions on a fragment of the Singapore Stone — part of a boulder once located at the mouth of the Singapore River — suggest that Tamil connections with Singapore go as far back as 1,000 years. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)1

Over the centuries, Singapore chalked up a complex history of connections with empires near and far. The inscriptions on a fragment of the Singapore Stone — part of a boulder once located at the mouth of the Singapore River — suggest that Tamil connections with Singapore go as far back as 1,000 years. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)1

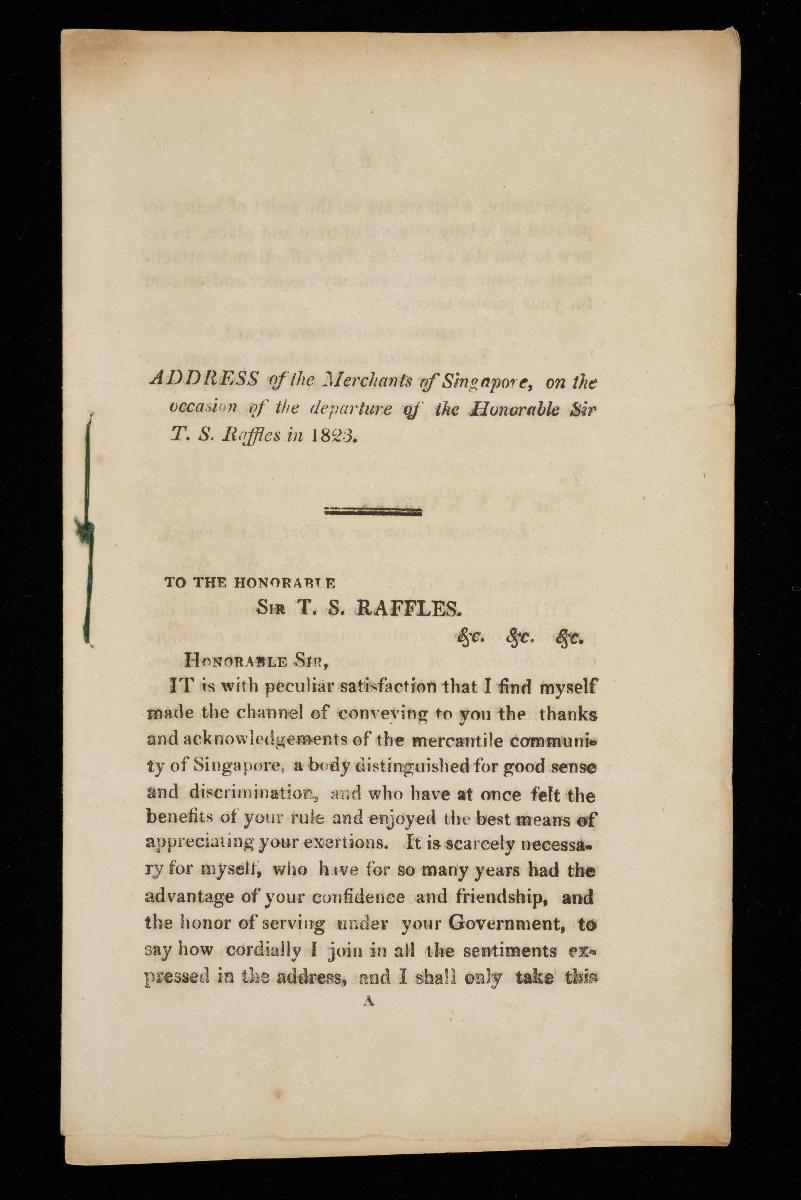

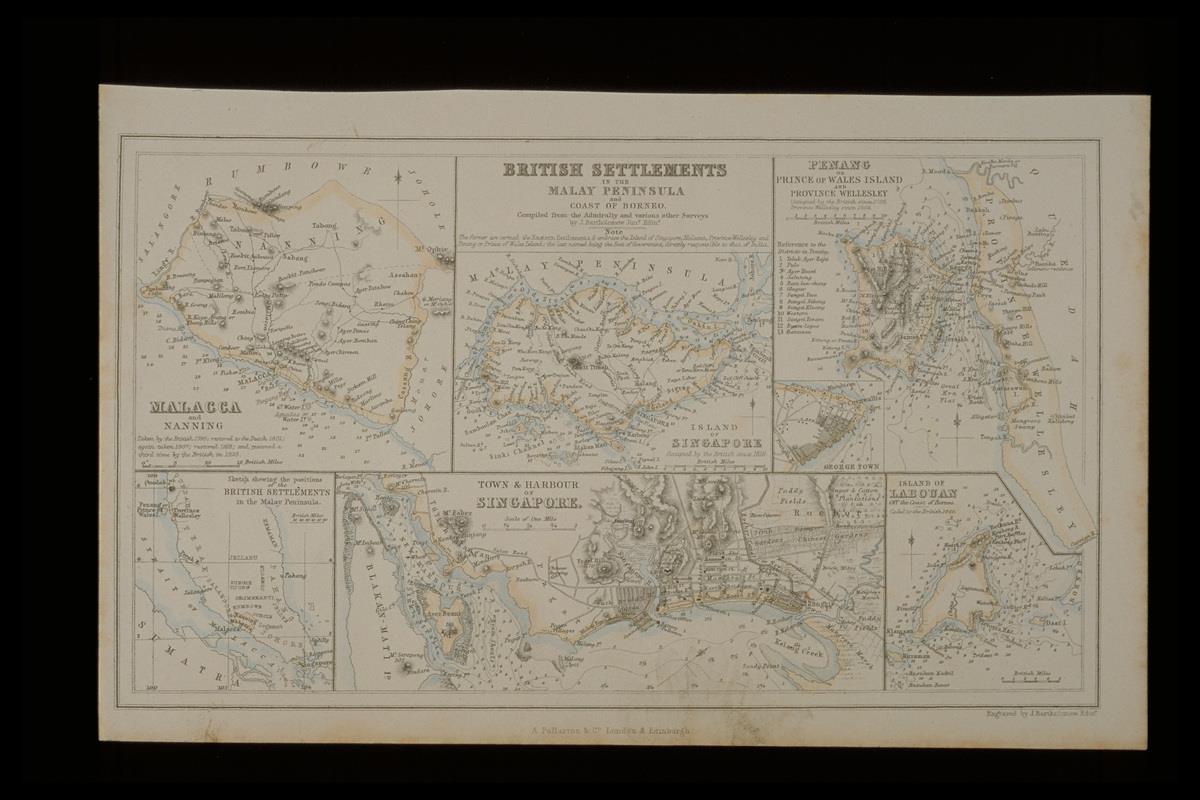

Sitting on the tip of the Malay Peninsula where sea routes intersect, the island of Singapore had long impressed mariners, traders and rulers for its strategic location, good rivers and great potential.2 The British were similarly enamoured by Singapore some centuries later. Under their charge in the 19th and 20th centuries, the ancient port was revived, attracting a melting pot of immigrants who together with founder Stamford Raffles, and British residents of Singapore William Farquhar and John Crawfurd, helped build a thriving emporium and shape the city we know today.

An 1817 portrait of Sir Stamford Raffles. In a bid to prevent the Dutch from monopolising trade, Raffles set about looking for a new trading base in the Malay Peninsula. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore.)

An 1817 portrait of Sir Stamford Raffles. In a bid to prevent the Dutch from monopolising trade, Raffles set about looking for a new trading base in the Malay Peninsula. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore.)

Spurred by Dutch pressure

In 1818, the Dutch set up a military post in Riau with the support of the Johor Sultanate. This move gave them control of a critical trading passage through the Strait of Malacca.3 It also gave them the liberty to impose heavy taxes on British ships at their ports.4

The Dutch stratagem was effective in persuading the British to relinquish control of the region, however Englishman Stamford Raffles was keen to protect British commercial interests. To this end, he embarked on a mission to hunt down a new trading base near the Malay Peninsula for the British East India Company.

In January 1819, a fleet of eight ships led5 by Raffles explored the possibility of hoisting the British flag on Indonesia’s Karimun islands. The islands however, proved to be too rocky.6

On the recommendation of hydrographer Daniel Ross, who was in charge of the party's survey ships, they made their way to Singapore.7 The island passed muster. It lay along the British trade route towards the Straits of China and boasted a natural sheltered harbour by the mouth of the Singapore River. With the notable absence of the Dutch, Raffles acted quickly to establish a trading post.8

This statue of Stamford Raffles has since been moved to a spot along the Singapore River where the British were believed to have landed in 1819. (c. 1905. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

This statue of Stamford Raffles has since been moved to a spot along the Singapore River where the British were believed to have landed in 1819. (c. 1905. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Securing Singapore as a trading post

The island’s chief, Temenggong Abdul Rahman, met with the party and was open to the idea of a British trading post. To this end, a provisional agreement was drawn up.

Singapore, however, was part of the Johor Sultanate.9 To avoid legal disputes, Raffles needed its Malay sovereign to attach his name to the treaty. The sovereign, however, was in partnership with the Dutch.

Capitalising on an underlying power struggle within the sultanate, Raffles brought in Tengku Hussien Shah, the rightful heir to the throne. Hussein had been unceremoniously usurped by his younger half brother. In exchange for recognition as sultan of Johor, British protection and an annual allowance, Hussien signed off on the agreement with the East India Company.

10

The signing ceremony was attended by islanders, as well as Malay dignitaries and British officials and soldiers dressed in their finest.11 Under the terms of this treaty, the British, sultan and temenggong were to benefit equally from the venture.

Raffles, excited by Singapore’s prospects, famously described the island as “the most important station in the East; and, as far as naval superiority and commercial interests are concerned, of much higher value than whole continents of territory”.13

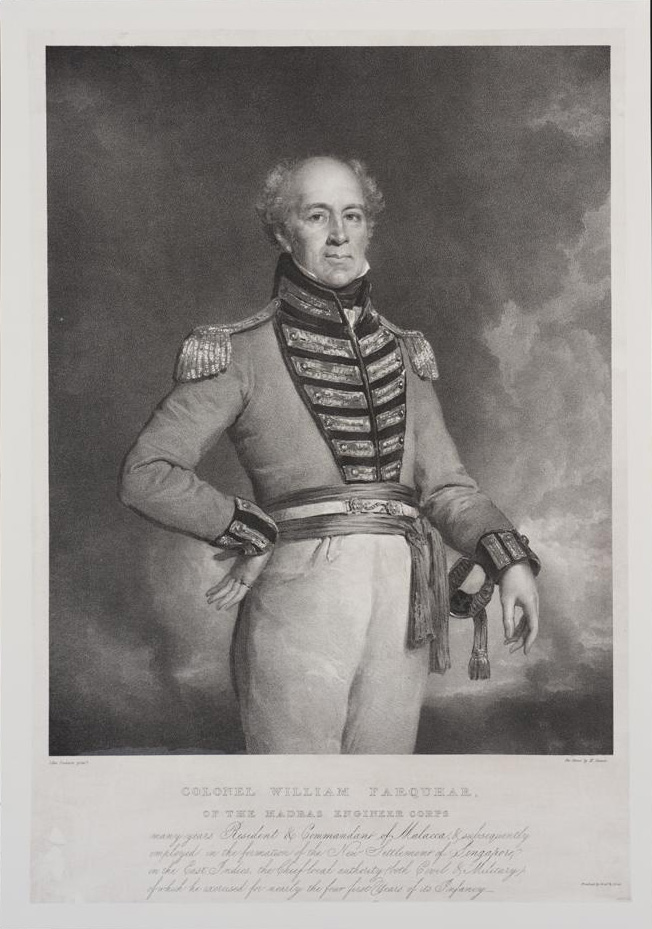

With the paperwork settled, Raffles left Singapore, leaving Major William Farquhar in charge as resident and commandant for four years.

During these years, land was cleared for mercantile houses, roads, and other amenities to facilitate business. A hillock in Battery Road was also levelled to build Raffles Place. Subsequently, this very earth was used to fill swampy land to create Boat Quay.14

By 1821, the island's population had multiplied from just 1,000 inhabitants two years before to about 5,000 — attesting to the success of the trading post.

Left to manage Singapore on a tiny budget, Farquhar enacted a plan to curb rising crime and raise money for public works, by selling licences for the provision of vices such as gambling, alcohol and opium. 15

In 1822, Raffles returned. He drafted a town plan to better organise the colony. It mapped out areas for key economic activities, as well as ethnic enclaves to separately house the settlement’s diverse and disparate communities for the sake of law and order, and his vision of communal harmony.

William Farquhar, the first resident of Singapore, clashed with Raffles vis-a-vis the management of the colony. Although he played a major role in running the settlement during its critical early years, he was dismissed by Raffles in 1823.

William Farquhar, the first resident of Singapore, clashed with Raffles vis-a-vis the management of the colony. Although he played a major role in running the settlement during its critical early years, he was dismissed by Raffles in 1823.

This silver epergne, an ornamental centrepiece to hold fruit or flowers, was presented to William Farquhar as a parting gift from Singapore’s Chinese community in 1823, signifying his popularity among locals. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

This silver epergne, an ornamental centrepiece to hold fruit or flowers, was presented to William Farquhar as a parting gift from Singapore’s Chinese community in 1823, signifying his popularity among locals. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Growing ambitions for Singapore

The British wanted to do more with Singapore but were held back by the terms of the 1819 treaty which they felt accorded too much power and a disproportionate amount of revenue to the temenggong and sultan.

They thus began nipping at their spheres of influence, eventually drawing up another treaty in August 1824 which they pressured the duo to sign. The British had the pair give up their powers and rights to the land for a lump sum pay out, raised allowances, and the permission to continue living in Singapore.

To further diminish their standing, the British sliced up the royal Malay area of Kampong Glam by having Victoria Street and North and South Bridge roads cut through the place.16

This lithograph depicts Kampong Glam and the Padang as viewed from Prinsep Hill in the 1840s. The British built a palace within a walled compound for Sultan Hussein Shah as part of the 1819 Singapore Treaty. The compound, which included burial grounds to the north, was reduced in the mid-1820s when North Bridge Road was constructed.17 (Image from the National Museum of Singapore).

This lithograph depicts Kampong Glam and the Padang as viewed from Prinsep Hill in the 1840s. The British built a palace within a walled compound for Sultan Hussein Shah as part of the 1819 Singapore Treaty. The compound, which included burial grounds to the north, was reduced in the mid-1820s when North Bridge Road was constructed.17 (Image from the National Museum of Singapore).

Upon the request of Sultan Hussein Shah, the British helped fund the construction of the single-storey Masjid Sultan in Kampong Glam.18 It was rebuilt (above) and completed in 1932. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Upon the request of Sultan Hussein Shah, the British helped fund the construction of the single-storey Masjid Sultan in Kampong Glam.18 It was rebuilt (above) and completed in 1932. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

The treaty made clear that the East India Company had full control of Singapore and its surrounding islands. A separate agreement signed between the British and the Dutch in 1824 further spelled out the territorial interests of both colonial powers. It specified, for instance, that the Dutch, which had full control of the Indonesian islands, would not launch a claim on the British colony of Singapore.19

To mark this official handover, a 21-gun salute was fired on three islands of Singapore including Pulau Ubin.20 John Crawfurd, who took over Farquhar as resident in June 1823, sailed around Singapore on his ship for 10 days in a further display of power.21

Crawfurd held the office of resident for about three years, sticking as closely as he could to Raffles’ ideals for the colony, while seeing through and retaining a fair number of Farquhar’s policies. Although less popular among locals than Farquhar, Crawfurd was generally regarded as an effective, prudent and conscientious administrator who successfully guided the colony’s next phase of growth and development.22 He, for instance, secured investments and helped Singapore set up a legal system.23

In 1826, Singapore became part of the Straits Settlements alongside territories such as Penang and Malacca.24

This 1827 print by Isaac Robert Cruikshank depicts John Crawfurd, the second Resident of Singapore, arresting merchant John Morgan. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

This 1827 print by Isaac Robert Cruikshank depicts John Crawfurd, the second Resident of Singapore, arresting merchant John Morgan. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

View of the Singapore River’s bustling harbour from Government Hill, present-day Fort Canning, as painted by James Marianne. The arrival of the British in 1819 helped set in motion Singapore's rapid growth and development. By 1828, the island had established itself as a formidable port-city. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

View of the Singapore River’s bustling harbour from Government Hill, present-day Fort Canning, as painted by James Marianne. The arrival of the British in 1819 helped set in motion Singapore's rapid growth and development. By 1828, the island had established itself as a formidable port-city. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)