TL;DR

Picture postcards were once heralded as embodying the spirit of modernity. But peer more closely at the images they portray and you will see colonial structures of dominance.

MUSESG Volume 16 Issue 2 - July 2023

Written by Assoc Prof Maznah Mohamad, Department of Malay Studies, National University of Singapore

Co-authored by Kathy Rowland, Co-founder and Managing Editor, ArtsEquator

Read the full MUSESG Vol. 16, Issue 2 - July 2023

An editorial by James Douglas published in the Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Advertiser in 1907 declared the dawn of that century as “the age of postcards”. The picture postcard was described as “the flower and crown of the modern spirit”.1 Although largely satirical in tone, the writer was not far off the mark in his description: by the early 20th century, postcards were so widely produced and used that one could conclude that they had truly taken the world by storm.

The postcard came into being in the late 19th century thanks to the technology of cameras and films, and the subsequent proliferation of photography studios. Picture postcards first appeared at the Paris Exhibition of 1889; by 1915, these nifty oblong-shaped paper products had become a feature of everyday life.2 Between 1894 and 1919, an astounding 140 billion postcards were mailed globally. In Singapore alone, 250,000 postcards were produced in 1924 by camera-maker Houghton Butcher (Eastern) Ltd whose office was located in Camera House on Robinson Road.

The ubiquity of the postcard also meant that images were easily circulated across the globe, reproducing new social and cultural contexts for their recipients and viewers. Postcards by Houghton Butcher (Eastern) Ltd were featured in the Malaya Pavilion at the 1924 Empire Exhibition in Wembley. Aimed at showcasing the achievements of British colonial governance, the Empire Exhibition displayed artefacts, trade samples and native people from the colonies for public viewing. Postcards became a significant medium for depicting subjects, places, activities and scenes of faraway colonised places that ordinary Europeans could access, albeit vicariously.

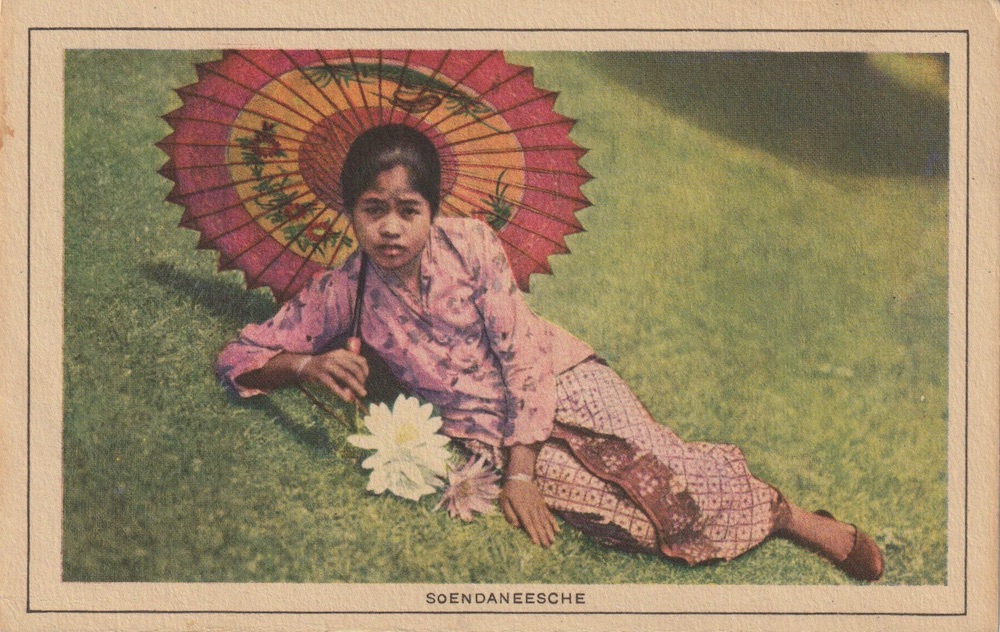

Scholars have argued that postcards were employed as objects of imperial dominance.3 These were visual products that had the power to signify, encode and legitimise imperial expansion.4 In archives and libraries all over the world, there exist enormous collections of postcards depicting ‘ethnic’ types—a form of colonial classification that excluded Europeans. The immense popularity and wide circulation of these postcards, whether advertently or not, helped define ethnic and racial categories within the mould of coloniser and the colonised.

A Vehicle for Vice

As the postcard grew into a commodity of mass consumption, interestingly, it also became a vehicle for vice and moral offences—particularly, obscenity. While picture postcards of idyllic beaches, exotic landscapes and vernacular architecture sold well enough, the ones that proved more lucrative were of women in sexualised or nude poses. By the 1900s, there were reports in Singapore of sellers and private distributors of postcards who had been charged with possessing obscene materials in the form of picture postcards.

In 1927, the Johor police seized a collection of postcards, “mostly of naked women”, which two men had attempted to sneak into Johor from Singapore. In his statement, the judge wrote that “Malays were very susceptible in these matters”, and gravely disapproved of “the exhibition of the female form in a naked state”.5

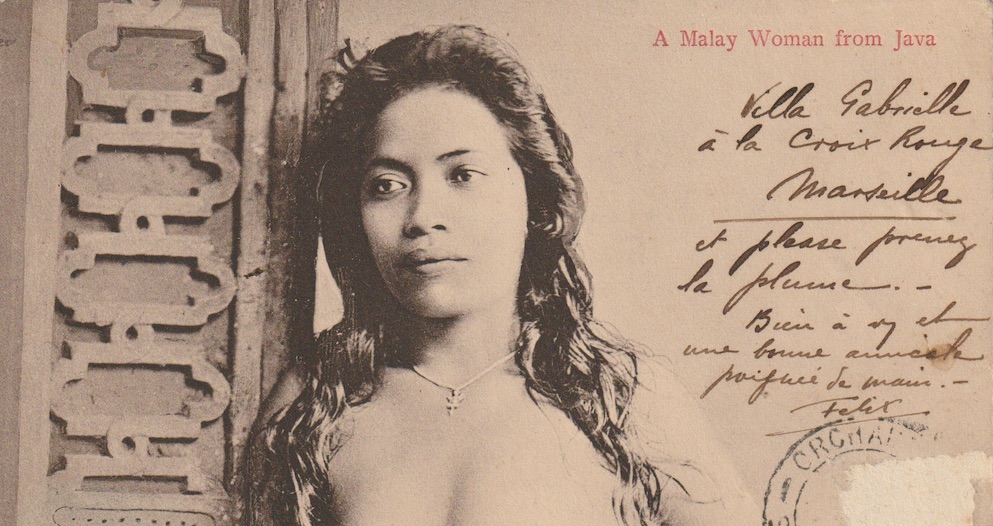

But the law was not so clear: some of these postcards were in fact permissible. Two decades earlier in 1907, a man was prosecuted for possessing such postcards. The prosecutor said that the accused was found to be selling “pictures of unlovely foreign women with nothing particular on, and the defence did not contend they were scientific [emphasis added]”.6 Thus, under the guise of ‘science’, one could print and reproduce photos of locals even if they were nudes—as long as the subjects were not Europeans.

Unsurprisingly, such was the thinking at the zenith of the British Empire: the pseudo-ethnographic style of images of colonised peoples, including the “unusual, taboo, and erotic”, was deemed to serve a scientific function—that is, the construction of a colonial storehouse of knowledge about native subjects. Photographs in library collections were often captioned with the phrase “on behalf of science” to legitimise their circulation and consumption.7

Alternative Ways of Seeing

Postcards were a form of colonial-driven transmission of ideas and consciousness, and their popularity coincided with the peak of European colonial domination from the late 19th century to the early decades of the 20th century. Thus, the study of postcards is very much a study of power and agency. Agency in this context refers to an individual’s capacity to act according to their will in a given situation. The images printed on postcards can also be seen as an extension of orientalism—an intellectual tradition of the West that involved the study of the peoples and cultures of Asia and the Middle East and which often perpetuated racial stereotypes.

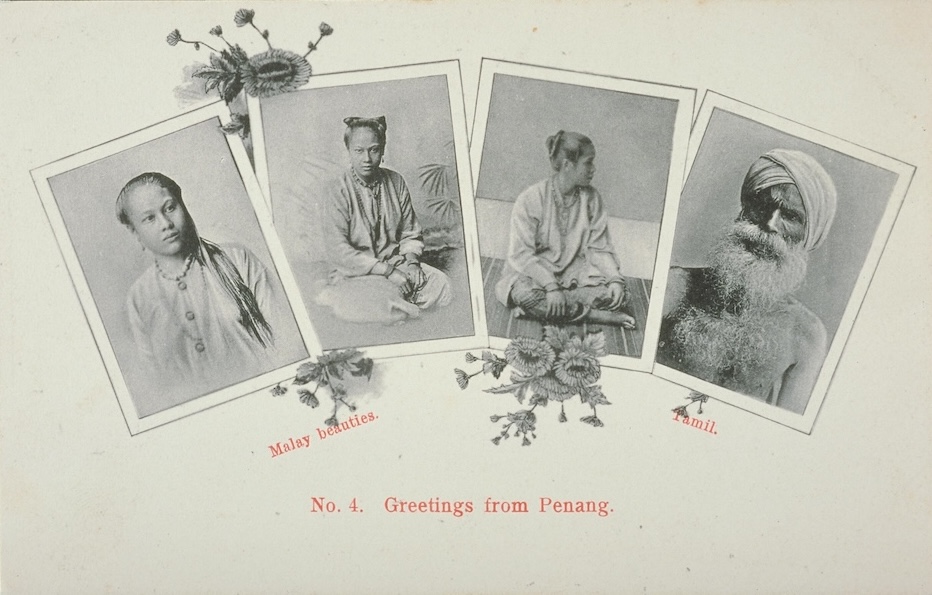

Inaccuracy and misrepresentation were par for the course. For instance, a postcard from Penang dated 1902 features the captions “Malay beauties” and “Tamil” (Fig. 2). However, pictured on the postcard are in fact the same woman in three different poses, while the “Tamil” man is actually a Sikh Punjabi. Postcards such as this one were not bound by any standards for accuracy and truth; instead, they were often produced for their curiosity value and to satisfy Western desires to consume the ‘exotic’ and ‘strange’ from other lands, in particular, of colonised peoples.

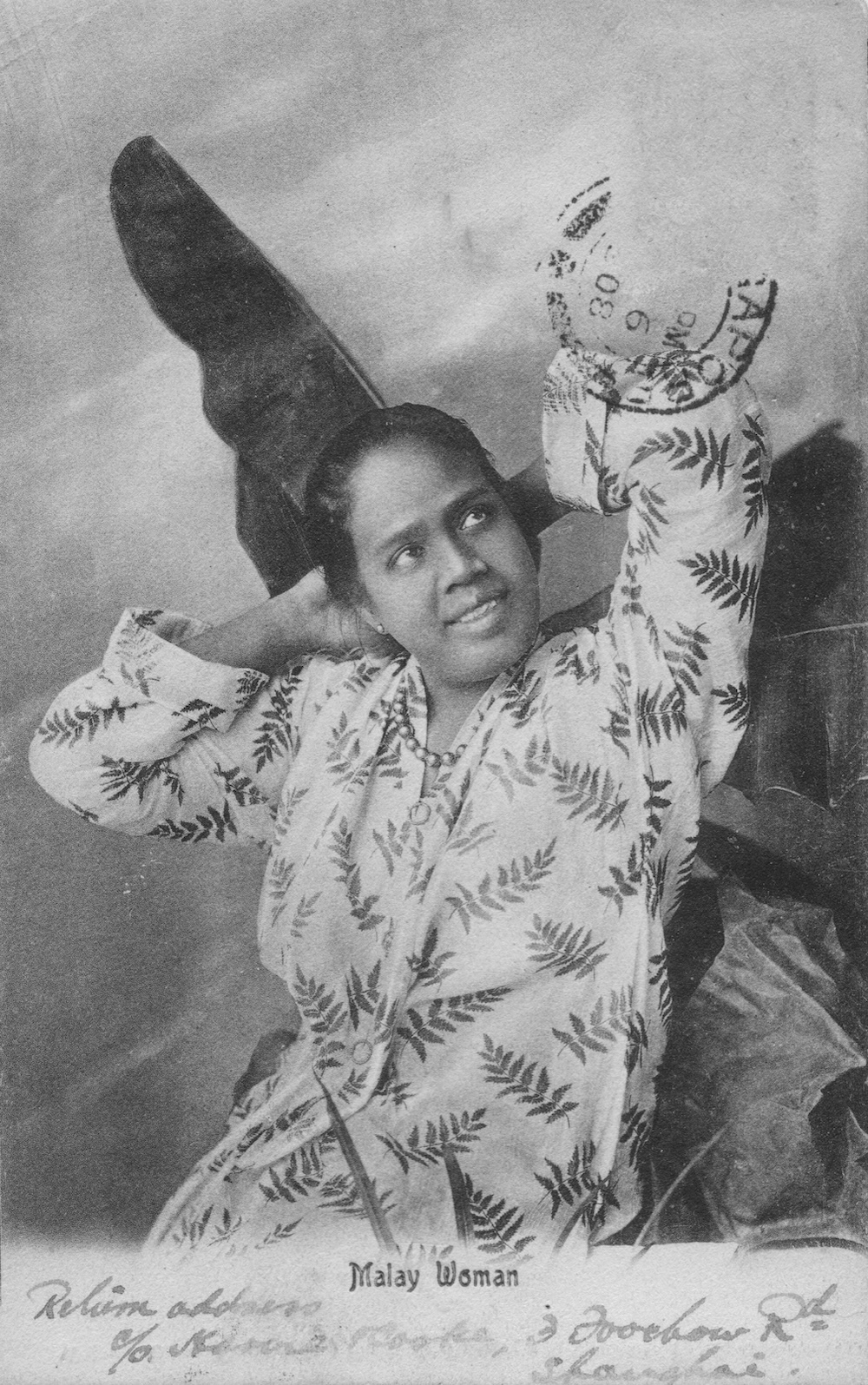

In another typical colonial-era postcard, we see a woman with her arms clasped behind her head, labelled simply as “Malay woman” (Fig. 3). The return address scribbled on the card is in Shanghai, although it is postmarked in Singapore. That such a postcard— bearing a supposedly definitive idea of what constitutes a ‘Malay woman’—had travelled halfway across the globe shows the circulatory power of this medium. This in turn perpetuates the singular, monolithic notion of the ‘Malay woman’.

Inadvertently, the invention of the camera8 and the ability to reproduce images also helped cement the dominance of the male gaze. There were few women photographers back then. In many of these postcards, women in the colonies were portrayed as erotic, uninhibited sexual objects.

In examples of photographed women from West Africa, Morocco, Fiji, Indo-China and Japan, subjects are often captured in poses that are almost entirely alike in terms of their objectification of women and girls as sexualised bodies. The subjects either appear in the nude or partially so, or pose in sexually alluring positions, against backgrounds depicting local objects to represent their distinct racial ‘types’. A woman from French Indo-China, for instance, might be pictured holding a fan.

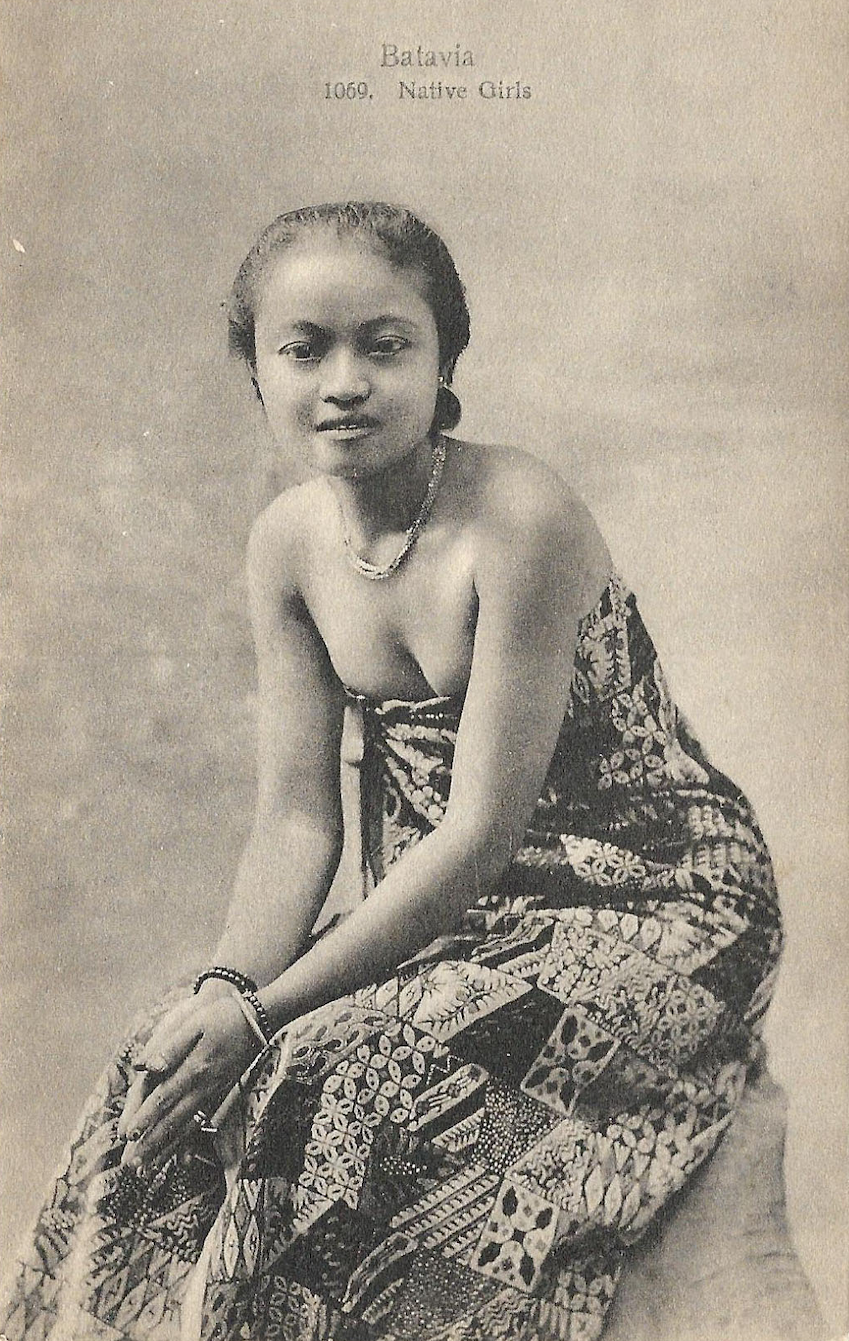

A postcard produced in Singapore featuring a bare-chested woman is captioned “A Malay Woman from Java” (Fig. 4). The woman is classified and typified as belonging to a racial category, with the added identifier of place. Such a label is meant to suggest the ‘scientific’ basis of photographing natives in the nude—an attempt to legitimise such overtly sexualised representation as an exercise in knowledge-making. The power dynamic between coloniser and the colonised manifests itself starkly in such photographic images through the authoritative photographer and the compliant photographed subject. Today, as we view these images from a vantage standpoint, from another era and embedded in a different social and political structure, how can we retain or reclaim the agency of the photographic subjects? How can one seek new ways of reading these images so that stereotypical, harmful ideas of women can be questioned and contested, or even inverted? There are two ways we can do this.

The Inverted Gaze

The first approach is to invert the gaze of the photographer to the gaze—or, in some instances, even glare—of the subject. By doing this, we demote the power of the photographer by returning agency to the subject who is staring straight into the camera lens.

In a postcard (Fig. 5) captioned “Malay woman, Singapore”, a woman wearing a shawl stares directly into the camera lens without the faintest trace of a smile. In fact, one may interpret her gaze as unfriendly or even angry. We cannot be sure that the subject’s pose was composed at the behest of the photographer, but we can at least read her facial expression in ways that reclaim—or misrecognise9—the usual impression of a ‘Malay’, ‘Islamic’ or ‘modest’ woman through the sartorial symbols of the veil and kebaya (a tunic with long sleeves).

In Figure 6, a young woman is depicted naked from the waist up while sitting at the edge of a chair—a pose that perhaps denotes some hesitation or nervousness. But we also sense that the woman is looking accusingly at the camera; reading more deeply into the image, one may perhaps even sense the subject’s simmering anger at being possibly coerced into posing in this manner.

Figure 7 shows a photograph of a trio of older women. Both the seated women stare intensely into the camera, while the woman standing between them looks sideways. We may deduce the hierarchical social status of the women: the pair seated are in a position of authority and the woman standing is in their service. With their seated poses and arms placed confidently at their sides, the gaze of the two dominant women is fixed, appearing almost defiant.

Dialogical Encounter

The second approach to re-reading images is to use a comparative device. In this method, selected photographs are placed together such that they generate multiple meanings, depending on how they are grouped. From this, we are able to tease out critical dialogues or narratives from these photographic encounters.

When studied side by side, Figures 8 and 9 invite comparison about their enmeshed notions of sensuality and modesty. Both women adopt the same pose: sitting on a rock, with their bodies leaning forward slightly. Perhaps the photographer meant to highlight the sensual character of native women, particularly so in Figure 8 where the subject is dressed in a sarong that reveals her cleavage.

A sarong worn in this manner is known as the berkemban, typically only seen in informal settings such as bath times or when cooling off in the surrounds of the home, among family and friends. In this postcard, however, the berkemban has been reconstituted to exoticise and sexualise the subject. The staged artificiality of the image is further highlighted by her jewellery—necklace and bangles are used to add beauty and charm to the subject when in reality she would have removed these for practical reasons.

Compare this with the subject in Figure 9 who wears a kebaya and thus appears very modest. The use of women’s bodies to imprint the sensibility of the times—one captured at the height of colonialism in the early 20th century and the other at the dawn of postcolonialism in 1950s—is starkly represented in the pairing of these two images.

In Figure 10, we may read strength and authority in the faces and postures of these three older women; it is almost as if they are defying the set poses typically suggested by the photographer. They are standing matter-of-factly without their shoes on, no suggestion of a smile on their faces, and staring straight into the camera. Although they are labelled as “Malay Women”, their facial features suggest they may in fact be Chinese Peranakan.

The trio of younger women in Figure 11, on the other hand, are clad only in sarong and appear to be in artificially staged poses that hint at sensuality. When we place these two images side by side, we can feel the power of the piercing stare of the three older women—most obviously directed at the photographer, but we can also imagine the older set of women looking askance at the younger women.

Together, Figures 12 and 13 make for a pleasing comparison or complementarity. It is likely that these photographs were taken around the same time, circa 1890s: it was fashionable then for Malay women to wear a veil made of a diaphanous material and ever so slightly sweep the hair over the forehead. Through their elegant attire and poses, both women seem to exude an aura of modesty, pride and dignity. When placed side by side, one can almost sense the way they are ‘looking’ at each other, as if silently communicating mutual reassurance.

Reclaiming Dignity

Postcards provide historical clues about people, places, dressing and habits. These are artefacts that enrich the layers of historical knowledge that we accumulate of the past. Postcards may also be looked upon as a nostalgic material culture that is part of heritage preservation.

Yet, it is important to recognise that still images captured by the camera have for the longest time served as a basis for the construction of inaccurate perceptions and opinions, stereotypes and half-truths of those being studied, while affording those who engage with them the legitimacy of ‘science’.

The two methods of interpreting images described in this article —the inverted gaze and the dialogical encounter— enable us to puncture entrenched colonial and patriarchal fantasies built around the construction of Malay women’s frailties, fragilities and femininities as captured in photographic images. Through these alternative ways of seeing, we come to treat the images not as passive artefacts, but as a means to reclaim the dignity of the people who have been silenced, misrepresented or oppressed under various structures of colonial dominance and coercion.

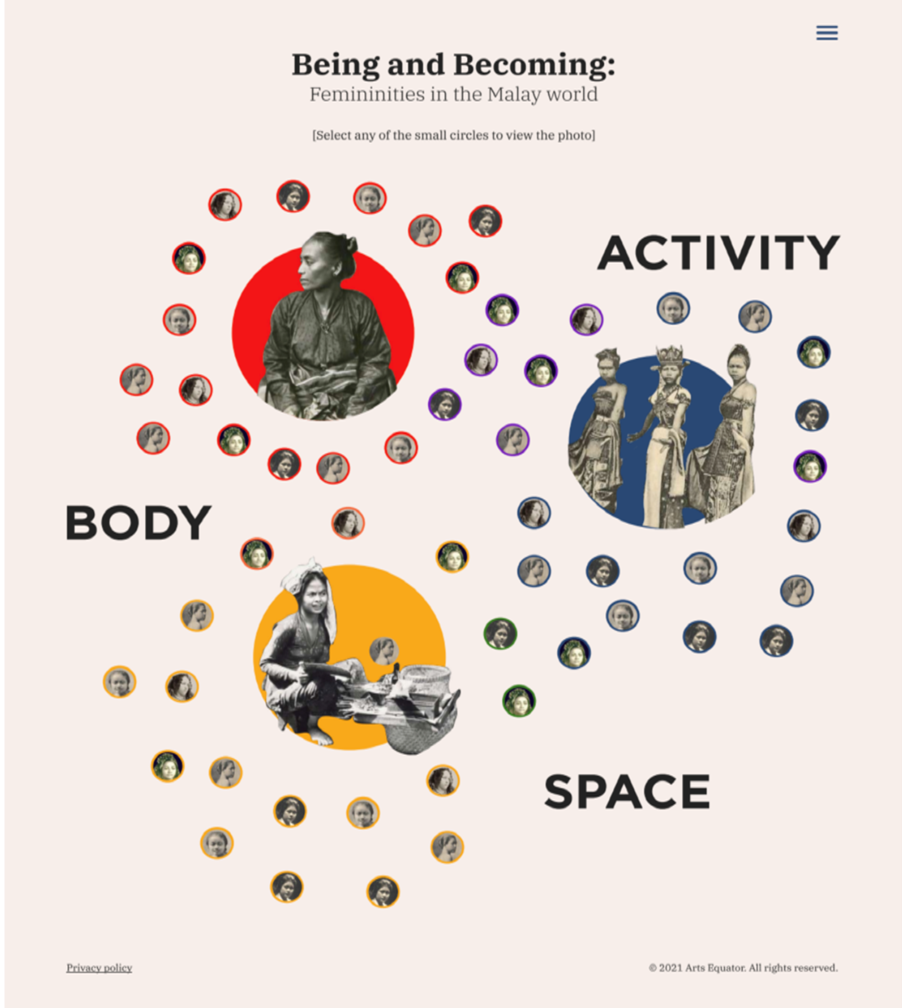

Being and Becoming: Of Femininities in the Malay World Through 50 Images

As part of the research project entitled ‘Being and Becoming Female in the Malay World: Interrogating and Curating the Photo-Archives of Early Singapore’ supported by the National Heritage Board, an online exhibition titled Being and Becoming: Of Femininities in the Malay World Through 50 Images was held from 12 May–31 August 2022.

Through the curation of 50 iconic images, the exhibition invited audiences to reflect on the themes of colonialism and imperialism, as well as the origins of gender and ethnic classification. It also provided an opportunity for viewers to reflect and contemplate on the images and form their own personal insights. Covering the region of present-day Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia, the photographs were sourced from collections of archival images from the mid-1800s to the 1950s.

The interactive website was anchored on three major themes: Body, Space and Activity. The first theme, Body, questioned the power of the camera to frame and capture the subject. Based on the images, viewers were encouraged to reflect on the body as a site of social construction and inscription. By observing the subjects’ phenotype, skin colour, posture, expression, dress (or lack of), ornaments, accessories and compositional frames, audiences were led to read and question each representation.

The theme on Space examined how choices of interior/domestic, architectural and urban settings frame bodies and identities in the photographs. Besides acting as a backdrop, space has the ability to project the image’s intended narrative within which the subject is meant to be understood.

Activity, the final theme, featured photographs of women working in and outside the household. The work performed by women then, as it is today, played a significant role in generating income for the household.

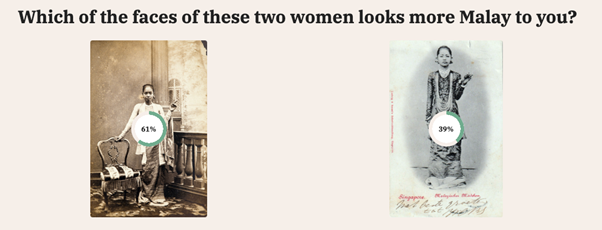

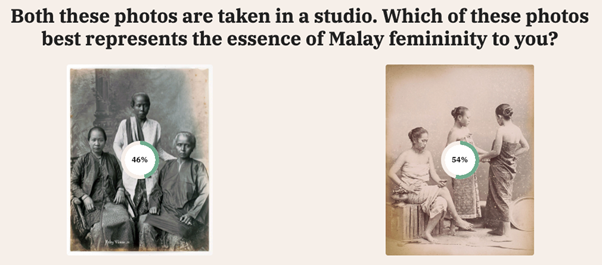

There were three interactive segments in the exhibition comprising multiple-choice, compare and contrast, and open-ended questions. By aggregating the responses received, researchers gained some understanding of certain perceptions of femininity—stereotypes, for example—that have persisted to this day.

For instance, in one compare and contrast question, viewers were asked to comment on two photographs of women (Fig. 15) dressed in Burmese attire and holding what appears to be a cheroot (a type of cigar) between their fingers. Most viewers found the images to be “jarring”. From this, we can surmise that many viewers were discomfited by the image of a traditional Asian woman in native dress engaging in an action that is usually associated with maleness—smoking. But it was in fact quite common for women in some societies to smoke in those days.

In another example featuring two photographs, each depicting a trio of women, respondents were asked which image better represented the “essence of Malay femininity” (Fig. 16). Viewers gravitated towards the photograph of the three lithe, bare-shouldered and sarong-clad young women whose poses (and faces) were averted from the gaze of the camera. The clear-cut popularity of this image when compared to the other— depicting three older women in full kebaya and baju kurung (a knee-length blouse worn over a skirt), all staring straight into the camera—implies that femininity today is still associated with youthful beauty, a slender body shape and a coy demeanour.

By engaging the public during the virtual exhibition and soliciting their responses, this virtual exhibition has contributed to the scholarship of how femininity in the Malay world has been represented through colonial photography.

Images courtesy of ArtsEquator

This article is adapted from ‘Being and Becoming Female in the Malay World: Interrogating and Curating the Photo-Archives of Early Singapore’, a research project supported by the National Heritage Board’s Research Grant.

Notes