Text by Nasri Shah

MuseSG Volume 10 Issue 1 - Jun 2017

The task of mapping the historical area of Kampong Gelam (often spelled as “Kampong Glam”) is a daunting one. One has to consider not only its labyrinth of former side streets and alleyways, but also the numerous paths and shortcuts traversed by the many that once worked and lived in the area. Although Kampong Gelam was gazetted as a conservation area in 1989, many of these routes and pathways had by then become a thing of the past. Various roads were expunged through the 1960s and 1970s, and business owners – including various printers and publishers – had already begun moving out or closing down their offices. To chart a trail through Kampong Gelam to better understand its history, it appears, is therefore always to be trailing behind its history, always a step too late to the scene of what was before.

Mereka Utusan: Imprinting Malay Modernity, 1920s–1960s was the Malay Heritage Centre's (MHC) fifth special exhibition, and it sought to recover the oft-forgotten history of the Malay language print and publishing industry in Singapore. In line with MHC's theme for 2017, Bahasa (Malay for "language"), the exhibition considered not only the language of the Jawi script used by Malay publishers of the time, but also the visual language of advertisements, editorial cartoons and comic strips prevalent in the Malay publications. More importantly, it restored the importance of Kampong Gelam as a node within a regional network of Malay printers, publishers and readers. The district’s importance reached a peak in the period between the 1900s to the 1950s, when no less than six printers and publishers could be found in various spots around Kampong Gelam.

As part of the exhibition, a guided trail consisting of stops at the sites of former printing and publishing offices in Kampong Gelam was held in March 2017. Entitled Di-chetak Oleh (Malay for “printed by”), the title references the small print often written at the bottom of the back of Malay magazines to denote their printing companies’ names.

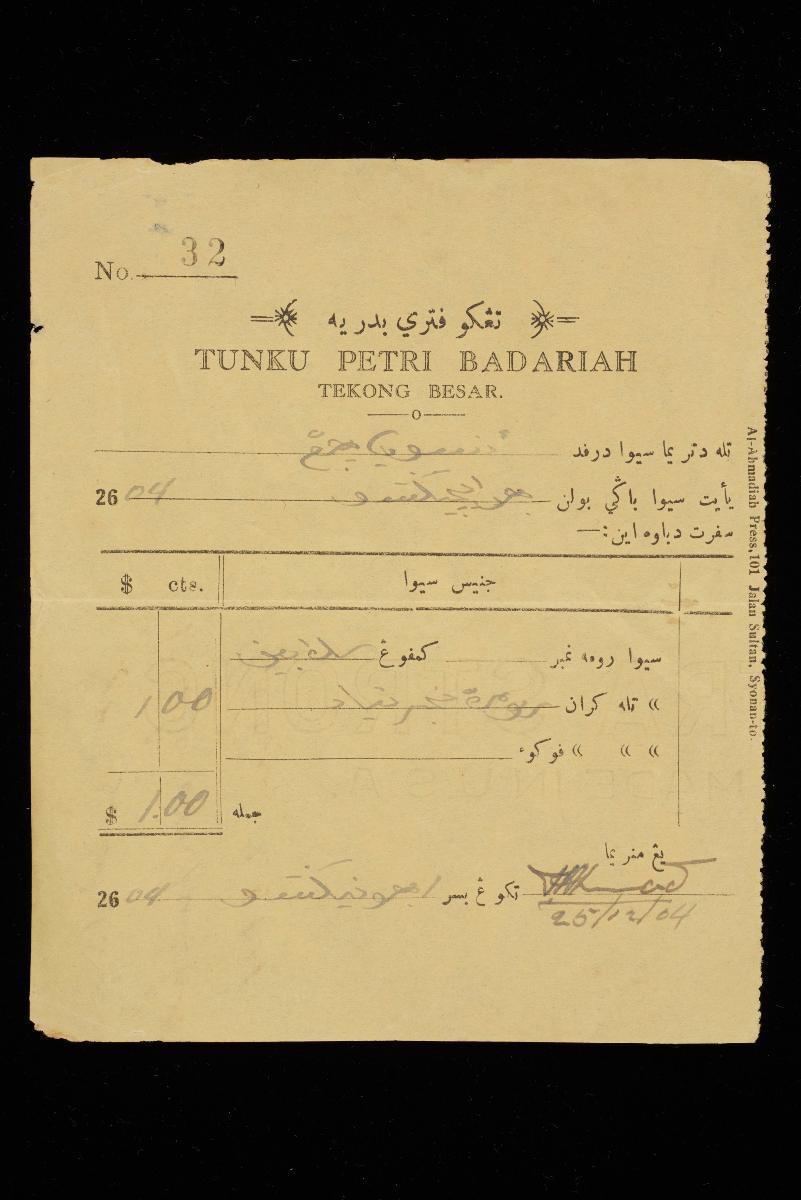

For example: Di-chetak oleh Al-Ahmadiah Press, Di-chetak oleh Qalam Press, and so on. For the team involved in the exhibition, the title also conjured memories of entire days spent close-reading and poring over hundreds of Jawi magazines kept in the MHC Collection, contributed by readers and former publishers.

In keeping with this spirit, the trail invited participants to contribute to the program by handling artefacts from this archive as well as those shared by our exhibition partners during the course of the trail. Participants then shared their reactions to these objects and artefacts, as if they too were helping to piece together this now-lost history of Kampong Gelam.

These objects and artefacts which the participants handled consisted of Jawi magazines from MHC’s education collection, and lead letterpress types that would have been used by Malay printers and publishers. A special treat for the participants was getting to experience a scent specially created by leading international fragrance company, Givaudan, whose perfumers were inspired by their trip to MHC’s Pustaka (the term “pustaka” encompasses language, literature and publishing) gallery. The intent behind these trail aids was to create a trail that was impressionistic rather than didactic, and was reminiscent of French writer Michel de Certeau’s musings of walking aimlessly in the city and being bombarded by “the chorus of idle footsteps”. For many who lived and worked in Kampong Gelam, these impressions were their guide to the area. Through speaking with Mr Abdul Aziz bin Abu Talib, a descendant of the owner of Royal Press (formerly located at 745 North Bridge Road), who was in his 60s, the curators discovered that his memories of navigating Kampong Gelam as a young printing apprentice to his father were filtered through such impressions as bicycling through the area, pulling eight-hour workdays in the printing office and wandering between the various side streets.

Such impressions of navigating Kampong Gelam provide a contrast to town plans, surveys and maps of the area which have been done as far back as the 1820s. Rather than providing clarity to the orientation of the area, these mapping projects were intended to rationalise the area for the purpose of future development and planning. It is not coincidental that such mapping projects of Kampong Gelam often preceded redevelopment projects, in which streets such as North Bridge Road and Victoria Street were paved and other streets such as Palembang Road and Jeddah Street became expunged over time. The irony, then, of such clear-eyed mapping projects and route surveys is the ultimate alteration of these very spaces.

Rapid development in the Kampong Gelam area, particularly in 1960s to 2010s, has therefore created what de Certeau refers to as “blind spots” within our field of vision towards “space itself”. This includes the history of that particular space, the organic interactions that take place within it, as well as its activities – all of which would escape a detached overview of that space.

The printers and publishers of Kampong Gelam are just some of the many historical agents who have since slinked off into these so-called “blind spots”, particularly in the aftermath of a ban on printing factories within the area in the 1990s. Only traces of these printers and publishers remain in the physical landscape of Kampong Gelam today, barely discernible amidst the rows of textile shops, dimly lit massage parlours, watering holes and bustling family eateries. With the exception of a few architectural hints, there is nothing to indicate, for example, that a thriving KTV pub along Arab Street was once the site of a printing office for the religious magazine Al-Imam, or that the popular toy store along Bussorah Street once attracted a crowd of a different sort in the early 19th century as the office of Javanese printer, Haji Muhammad Siraj. In this regard, the trail aids also help participants to imagine for themselves a historical impression of the area as it would have been like at different points in time.

Continuities do, however, exist between present sites in Kampong Gelam and their past incarnations as printing offices. The site of Islamic Restaurant, currently located at 745 North Bridge Road, is still owned by the family of Abu Talib bin Ally as of 2017, who previously ran Royal Press. In a different manner, the Sultan Hotel’s tours at its three-storey shophouse unit has also served to introduce visitors to the building’s previous history as the site of Al-Ahmadiah Press and HARMY Press.

Interacting with the family of Abu Talib bin Ally and the management of the Sultan Hotel revealed a second and possibly more important aspect of the trail. Through this trail, museum practitioners were pushed to engage with the descendants and inheritors of these legacies. Whilst the trail aids filled gaps in the historical narrative of the area, it was these anecdotes from people who formerly lived and who continue to work in the area that enlivened the trail.

Engaging such individuals and families also facilitates MHC’s efforts in building itself as an institution of and for the area from which it operates. In this regard, the exhibition could be seen as expanding upon the premise established by MHC’s 2015 exhibition – Kampong Gelam: Beyond the Port Town which considered the cultural, economic and social histories of Kampong Gelam. This exhibition and trail continues to follow that train of thought, by looking specifically to the printers and publishers of the area, who in many ways contributed to the economic and cultural vibrancy of the area. Indeed, from the heart of a port town, one is invited to cast a closer look at the many printing and publishing offices that once called Kampong Gelam home.