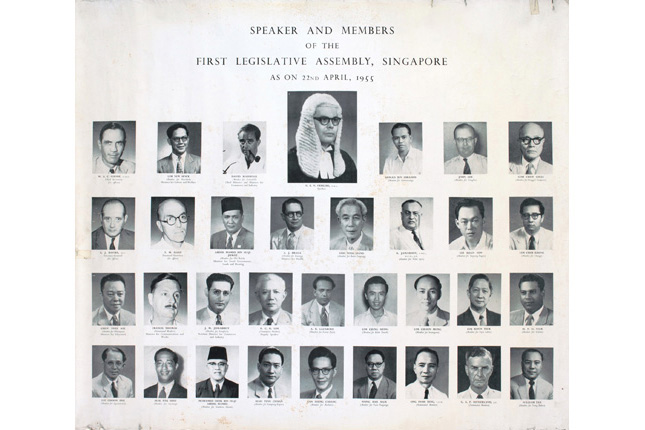

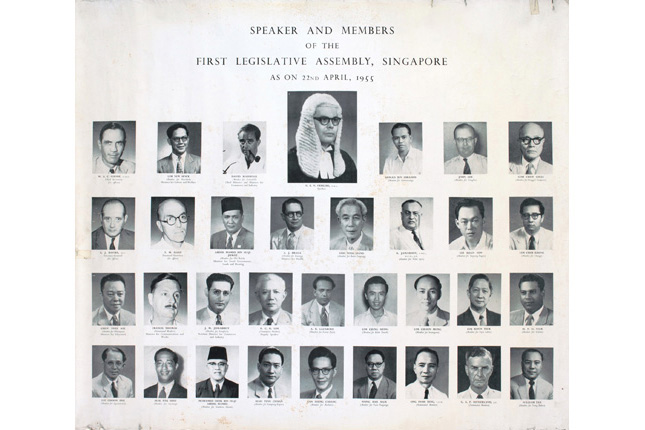

A poster titled ‘Speakers and Members of the First Legislative Assembly, Singapore’. David Marshall can be seen on top row, third from left. (c.1955)

A poster titled ‘Speakers and Members of the First Legislative Assembly, Singapore’. David Marshall can be seen on top row, third from left. (c.1955)

From textiles to law

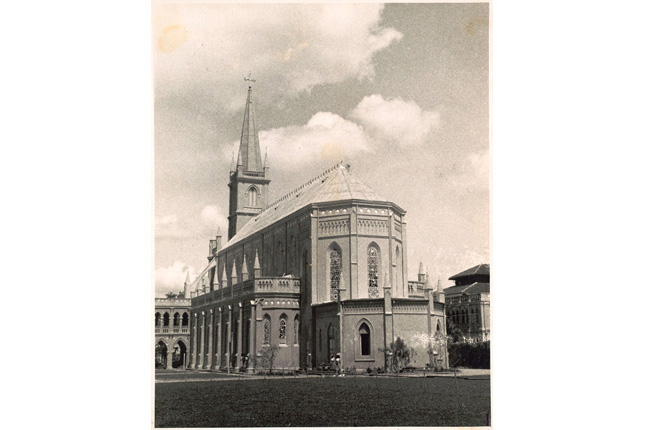

Born in Singapore to Saul Nassim Mashal,4 David Marshall, whose name was anglicised in 1920,5 was raised in a Jewish orthodox family alongside six younger siblings. School life for him started at a kindergarten run by the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus.6

As a student at Raffles Institution, Marshall became friends with individuals such as Benjamin Sheares and George Oehlers – fellow future leaders of Singapore.

During the course of his education, Marshall attempted to apply for the highly sought-after Queen’s Scholarship. However, being of weak constitution, he collapsed before he could take the exam. Marshall thus pivoted to the field of textile manufacturing which he pursued in Belgium.

Back home in Singapore, he worked as a textile representative and a French language teacher.7 Before he turned 30, Marshall decided to read law.8

A patriot at heart

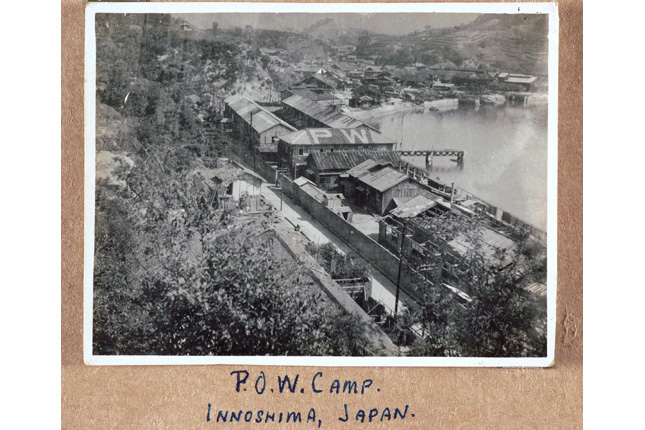

When World War II came around, Marshall’s family fled Singapore. He, however, chose to stay behind, going so far as to join the Singapore Volunteers Corps “B” Company to defend the island. Unfortunately, he was captured in February 1942 and detained as a Prisoner-of-War (POW) for three years and six months.9

Even under the oppressive rule of his Japanese wardens, Marshall’s outspoken personality and energy shone bright. A champion of justice, he frequently spoke up for the rights of his fellow prisoners. This drew the ire of his captors who tried to limit his influence.10 Over the course of his internment, Marshall was moved to multiple POW camps and even to a forced labour site in Hokkaido, Japan.11

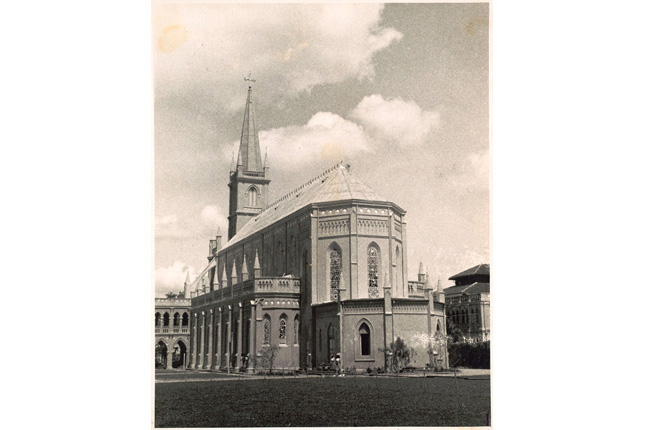

Founded by Father Jean-Marie Beurel in 1854, the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus (CHIJ) - otherwise known as Town Convent - was a Catholic girls' school that also took in boys, including Singapore’s first Chief Minister David Marshall, for a period of time from the 1900s till the Japanese Occupation. (Early-mid 20th century)

Founded by Father Jean-Marie Beurel in 1854, the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus (CHIJ) - otherwise known as Town Convent - was a Catholic girls' school that also took in boys, including Singapore’s first Chief Minister David Marshall, for a period of time from the 1900s till the Japanese Occupation. (Early-mid 20th century)

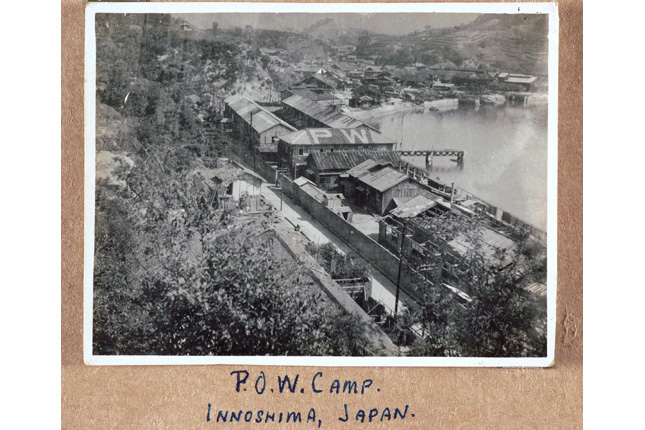

This Prisoner-of-War (POW) camp in Innoshima, Hiroshima was probably one of the 26 POW camps that David Marshall was sent to during the Japanese occupation. (c.1940s)

This Prisoner-of-War (POW) camp in Innoshima, Hiroshima was probably one of the 26 POW camps that David Marshall was sent to during the Japanese occupation. (c.1940s)

Foray into politics

After the war, Marshall completed his law degree and worked at a number of law firms such as Aitken and Ong Siang, and Allen and Gledhill in Singapore.

In 1949, he joined the Singapore Progressive Party for about three years.12 Later, in March 1955, guided by his desire to boost the standing of the people of Singapore,13 Marshall decided to put his legal career on hold to focus more on politics. Among other things, he was determined to banish “racial superiority” and “break through sonic barriers against Asians and especially Jews”.14

The same year, the Labour Front party led by Marshall was victorious in the Legislative Assembly election.15 It had secured 10 of the 17 seats it contested, and formed a coalition government with the Alliance Party. Marshall himself won a seat in Cairnhill and became Singapore’s first elected chief minister.16

The Labour Front contested in the 1955 Legislative Assembly Election and secured the most votes. As it did not win by a majority, it formed a coalition government with the Singapore Alliance Party and Marshall became Singapore’s first Chief Minister (c.1957)

The Labour Front contested in the 1955 Legislative Assembly Election and secured the most votes. As it did not win by a majority, it formed a coalition government with the Singapore Alliance Party and Marshall became Singapore’s first Chief Minister (c.1957)

A brief tenure

As chief minister, Marshall tried to pursue self-governance and independence from the British. However, before he had the chance to warm his seat, the communists began giving him trouble. Civil unrest in the form of the Hock Lee Bus Riots,17 as well as the other unpredictable antics of Singapore’s growing left-wing movement, kept him busy.

Although he was unsuccessful in attaining self-governance for Singapore, Marshall left a lasting legacy. While at the helm, a white paper on education policy was put forth advocating for more focus on the English language as well as multilingualism – fundamental features of Singapore's education system today.18

Invested in fighting for workers’ rights, Marshall was also instrumental in passing the Labour Ordinance to put an end to long work shifts. Additionally, he was involved in the introduction of schemes to help locals secure employment in the British-dominated civil service.19

Following unsuccessful talks with the British about self-governance for Singapore,20 Marshall resigned on 7 June 1956 after a brief 14-month tenure.

His political contributions, however, did not stop there. A year later, he founded the Workers’ Party. Thereafter, he contested the Anson by-election, and on 15 July 1961 won a seat in parliament. In 1963, Marshall left the party21 and resumed his law career.22

Marshall was outspoken about his beliefs, and was against capital punishment as well as the abolition of the trial by jury system. His drive and passion led him to score acquittal after acquittal over the span of 41 years.

Upon the invitation of then Foreign Minister S. Rajaratnam, Marshall went on to serve as Singapore’s first foreign ambassador to France, Spain, Portugal, and Switzerland from 1978 to 1993.23

Chief Minister David Marshall at a meet-the-people session, meeting 40 busmen regarding the arrest of their leader, secretary of the Singapore Bus Workers Union, Fong Swee Suan, who was under emergency detention. (c.1955. Image from National Archives of Singapore)

Chief Minister David Marshall at a meet-the-people session, meeting 40 busmen regarding the arrest of their leader, secretary of the Singapore Bus Workers Union, Fong Swee Suan, who was under emergency detention. (c.1955. Image from National Archives of Singapore)

Chief Minister David Marshall on a goodwill visit to Jakarta in 1955. (c. 1955)

Chief Minister David Marshall on a goodwill visit to Jakarta in 1955. (c. 1955)

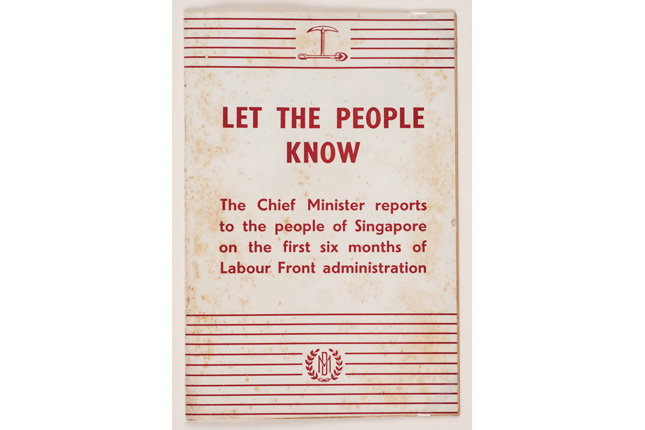

Marshall’s style of governance rested on a high degree of accountability to the people. This booklet provides a detailed report of what his Labour Front government had done in its first six months (c.1955)

Marshall’s style of governance rested on a high degree of accountability to the people. This booklet provides a detailed report of what his Labour Front government had done in its first six months (c.1955)

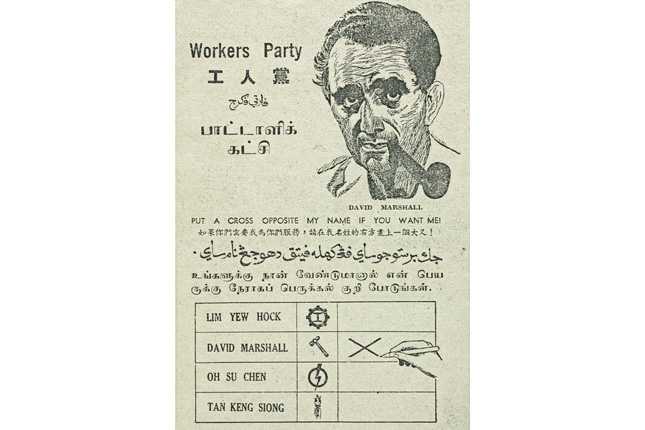

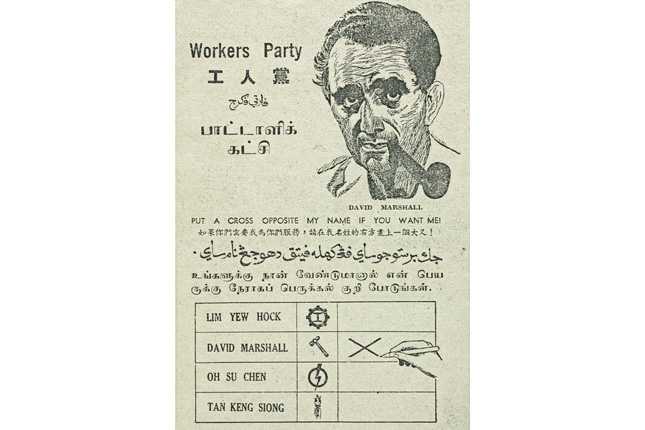

This was the campaign card used by David Marshall during the Anson by-election of 1961, in which he contested – and won – as President of the Worker’s Party that he founded in 1957 (c.1961)

This was the campaign card used by David Marshall during the Anson by-election of 1961, in which he contested – and won – as President of the Worker’s Party that he founded in 1957 (c.1961)

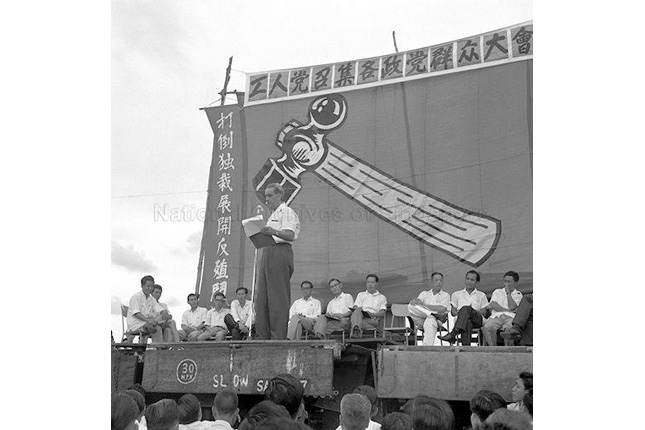

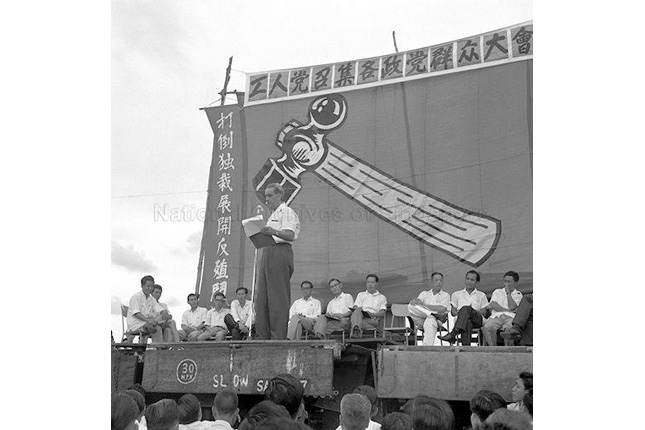

Leader of Workers’ Party David Marshall speaking at a rally on Referendum Bill at Shenton Way. (c.1962. Image from National Archives of Singapore)

Leader of Workers’ Party David Marshall speaking at a rally on Referendum Bill at Shenton Way. (c.1962. Image from National Archives of Singapore)

Legacy in criminal law

Stricken with lung cancer, Marshall passed away at the age of 87 on 12 December 1995. Numerous scholarships and fellowships, such as the David Marshall Professorship in Law and the Singapore Management University’s David Marshall Prize, were established in honour of his exemplary legal career.24

Chief Minister David Marshall visits Singapore Military Forces’ Camp at Tanah Merah (c.1955. Image from National Archives of Singapore)

Chief Minister David Marshall visits Singapore Military Forces’ Camp at Tanah Merah (c.1955. Image from National Archives of Singapore)

Marshall is best remembered during his Chief Minister days for his bush jacket, which created a stir in Parliament for its unconventionality, and the signature pipe that was a trademark on his office desk, which he was always puffing up to his last days. (c.1970s. Gift of Mrs. Jean Marshall)

Marshall is best remembered during his Chief Minister days for his bush jacket, which created a stir in Parliament for its unconventionality, and the signature pipe that was a trademark on his office desk, which he was always puffing up to his last days. (c.1970s. Gift of Mrs. Jean Marshall)