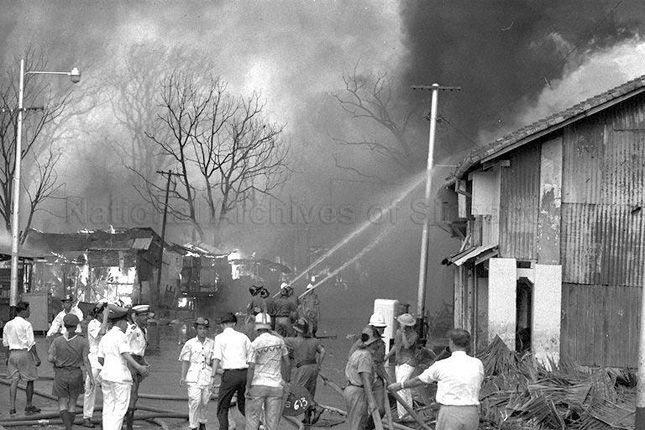

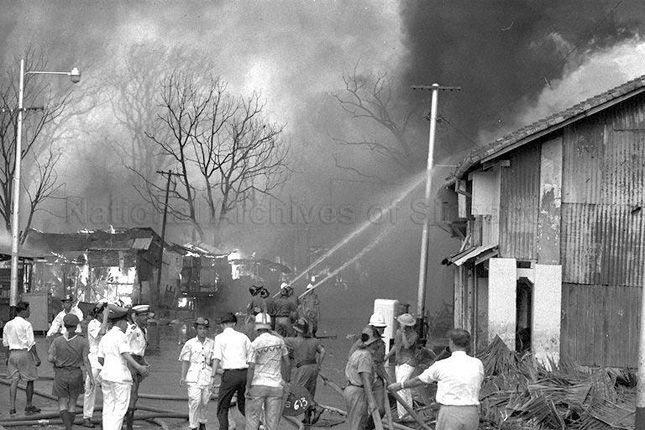

The Bukit Ho Swee fire displaced 16,000 kampung dwellers from their homes and killed four villagers in its wake. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

The Bukit Ho Swee fire displaced 16,000 kampung dwellers from their homes and killed four villagers in its wake. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

A razed village

Kampong Bukit Ho Swee was an unplanned township of 20,000 residents living in haphazardly-erected huts made primarily of materials such as wood and zinc. It experienced a population surge after World War II.2

On 25 May 1961, a small fire started innocuously enough in a makeshift squatter hut lying on its fringe – a hillside at Kampong Tiong Bahru Road. However, powerful winds that day caused it to escalate into a roaring blaze, carving a sweeping path of destruction. Ferocious flames, furtherxf fuelled by oil and petrol from the area’s godowns, leapt rather easily across the road to Kampong Bukit Ho Swee.3 The blaze ended up engulfing the kampong’s warren of homes, searing through its flimsy roofs and walls.

Eyewitnesses’ accounts as well as news reports document kampung residents scrambling for their lives with key belongings in hand and children in tow.

The low water pressure of nearby hydrants and the haphazard lay of Kampong Bukit Ho Swee impeded firefighters’ valiant attempts to put out the blaze. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore

The low water pressure of nearby hydrants and the haphazard lay of Kampong Bukit Ho Swee impeded firefighters’ valiant attempts to put out the blaze. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore

Since it was Hari Raya Haji, a public holiday, firefighters and police personnel had to be recalled from leave. They were pinged via repeated radio broadcasts. In all, 22 fire engines, 180 firemen, 20 police officers and nearly 1,000 army personnel were activated to battle the fire and help victims. Despite the strong show of force, luck was not on their side. Poorly pressured water hydrants, the kampung’s irregular, twisting alleys, and chaotic crowds clogging up entry points, made it near impossible to put out the fire.

The conflagration was only stopped in its tracks by an open space along Ganges Avenue. This prevented the fire from swallowing up flats across the road.5 The last of the flames were extinguished later that night at Delta Circus.

Rendering aid in the aftermath

With the fire put to bed, the authorities could now assess the damage. The blaze, they found, had taken with it shops, factories and a school in an area spanning approximately 40 hectares. According to official tallies, four lives were lost that day, 85 villagers were injured, and 16,000 people had lost their homes.6 The cause of the fire could not be determined.

To cater to the displaced, schools along Kim Seng Road were converted into temporary shelters. Government agencies, the military and volunteer organisations also banded together to offer much-needed support by providing essentials such as mattresses, water, gas, and electrical supplies.7

Yang Di-Pertuan Negara Yusof Ishak surveying the aftermath of the blaze. While there, he assured victims that the government would be taking swift action to provide them new homes. (26 May, 1961. Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

Yang Di-Pertuan Negara Yusof Ishak surveying the aftermath of the blaze. While there, he assured victims that the government would be taking swift action to provide them new homes. (26 May, 1961. Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

Meanwhile, at Kampong Bukit Ho Swee itself, 1,500 policemen had been deployed to patrol its charred grounds and protect occupants’ remnant belongings from looters.8 The authorities also worked to bury the carcasses of villagers’ perished livestock. Estimates placed villagers’ collective loss at approximately $2 million.9

Two days after the devastating incident, the Bukit Ho Swee Fire National Relief Fund Committee was set up by then Minister for Labour and Law K.M. Byrne. The committee eventually raised about $1.6 million to help victims get back on their feet.10

A safer way to live

Following emergency sessions with his cabinet as well as the Housing Development Board, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew assured victims a day after the blaze that they would be moved into new flats in areas such as Queenstown, Tiong Bahru, and even Bukit Ho Swee itself.11

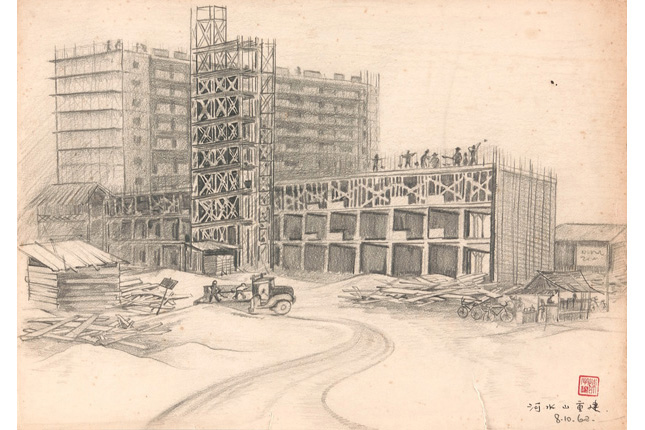

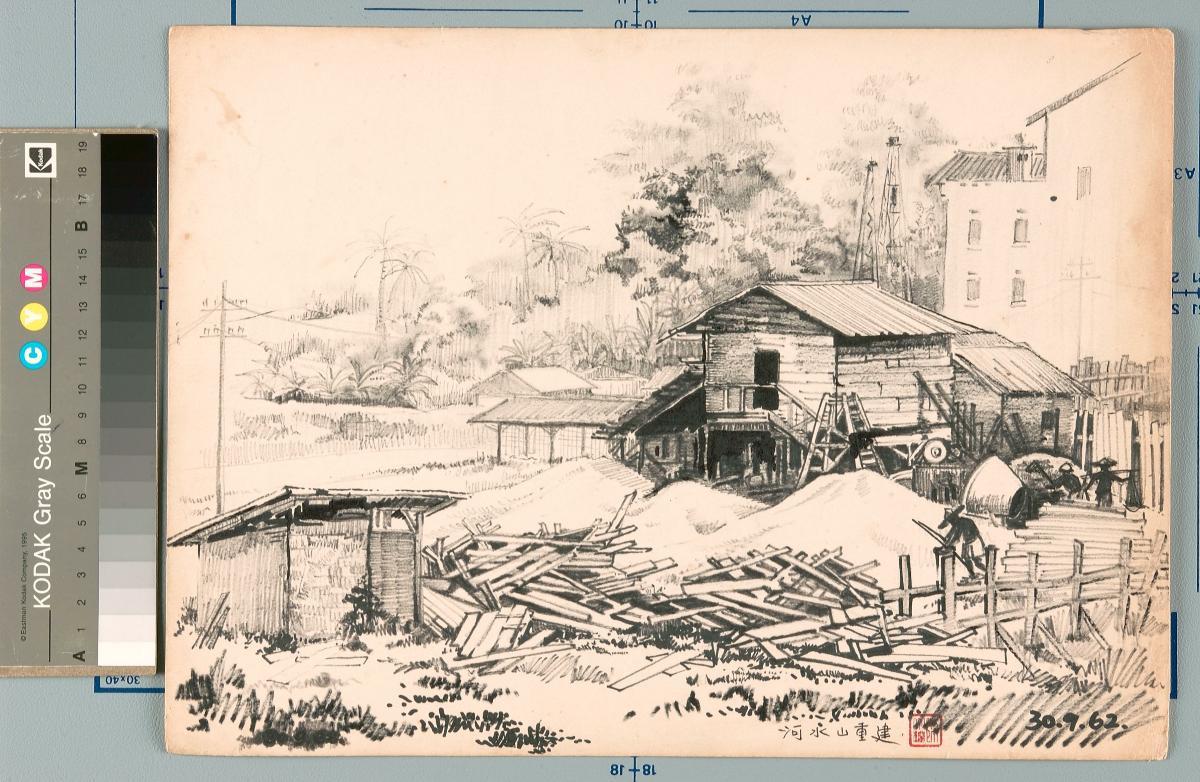

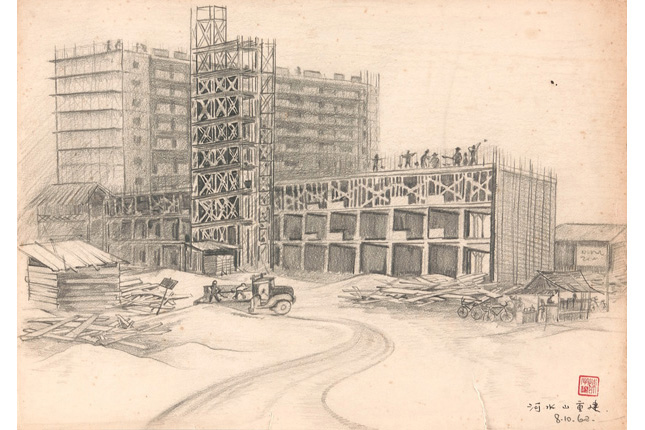

Artist Tan Choo Kuan’s interpretation of the Bukit Ho Swee rebuilding project. (c1962. Image from the National Museum of Singapore, Gift of Ms Tan Teng Teng)

Artist Tan Choo Kuan’s interpretation of the Bukit Ho Swee rebuilding project. (c1962. Image from the National Museum of Singapore, Gift of Ms Tan Teng Teng)

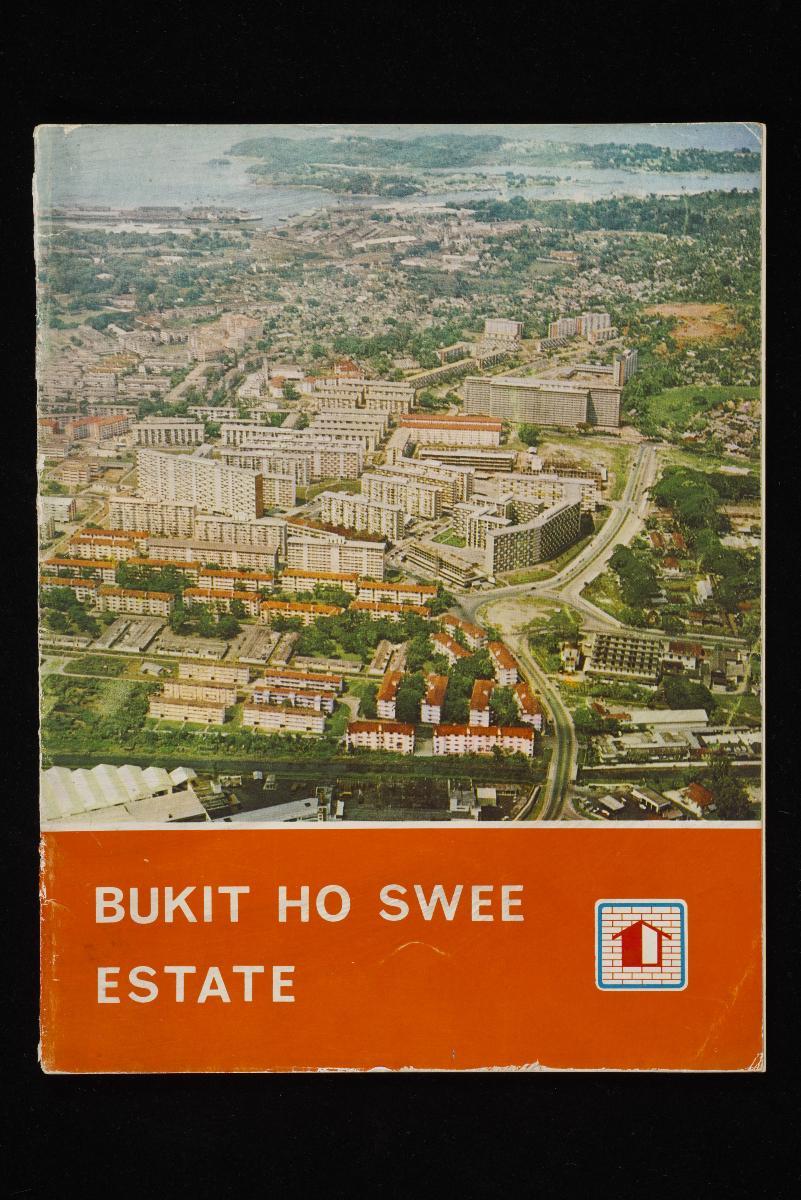

Among other things, the government worked to acquire the affected Bukit Ho Swee site for low-cost housing. It also amended the Land Acquisition Ordinance to facilitate this.12 There were several phases to this operation and by 1970, Bukit Ho Swee had successfully transformed into a new residential area boasting 12,500 flats for more than 45,000 residents – the majority of whom were residents of the former kampung settlement.13

The incident paved the way for newly-independent Singapore to kickstart a nationwide drive to relocate its kampung-dwelling population to safer, modern high-rise homes.

A watercolour painting of Beo Crescent, one of the estates which rose following the Bukit Ho Swee fire, as depicted by Singaporean watercolourist Ong Kim Seng. (c2008. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

A watercolour painting of Beo Crescent, one of the estates which rose following the Bukit Ho Swee fire, as depicted by Singaporean watercolourist Ong Kim Seng. (c2008. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)