By Dilip Basu

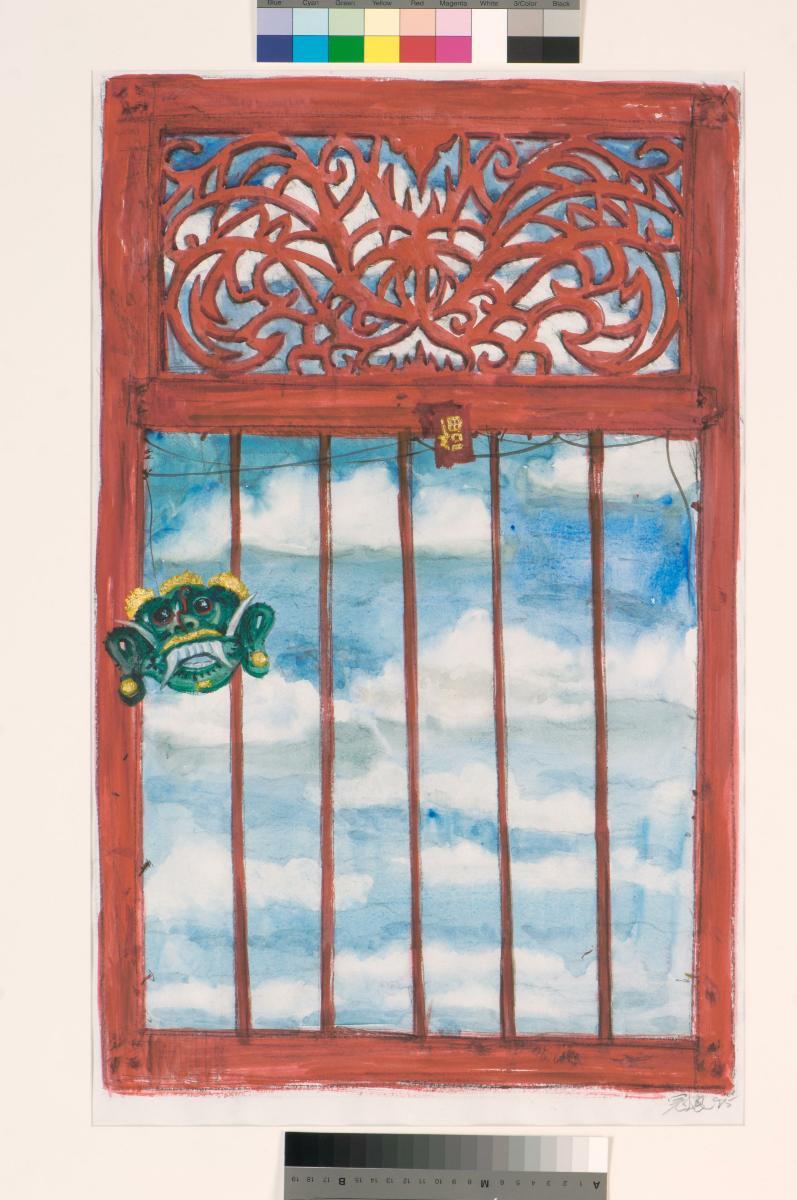

Images: Satyajit Ray Film and Study Centre, UCSC.

BeMuse Volume 3 Issue 4 - Oct to Dec 2010

Satyajit Ray is best known in the world of cinema as the maker of the Apu Trilogy (Pather Panchali, Aparajito, Apur Sansar), which is regarded as the greatest three-part film ever made. The Apu Trilogy is the most well known work of Indian cinema around the world. It is not so much about the storyline, but how it poetically captured life in a rural Indian village. In fact, the films do not have a conventional dramatic plot, but instead are episodic and follow the rhythm of the lives of the people they portrayed. But few if any apart from devoted Ray aficionados know that he made many more equally great films. Ray’s 36- film oeuvre comprises great and near-great films. Unlike his famed contemporaries like Bergman, Kurosawa, Fellini and Antonioni, who made a few “bad” movies along with some great ones, Ray never made a substandard, imperfect film. As the noted film critic and scholar Peter Rainer remarked: “Nobody made films like Ray before him, and it is unlikely anybody will after him.” Each lm Ray made is original and unique. No one can accuse him of “self plagiarism”. What is also remarkable is the incredible diversity and variety in his works.

Biographers of Satyajit Ray and film scholars writing on his prodigious output have tried to pigeonhole him in one way or another. He has been called a Bengali Bergman, a Calcutta Chekhov or a sort of reincarnated Renoir. One critic, Michael Sragow, describes Ray as the most sublime filmmaker to emerge since Renoir and De Sica. In the West, most scholars assume that Ray, artistic and somewhat offbeat, must have emerged from India’s large and prolific motion picture tradition. In India, Ray was initially dismissed as a peddler of poverty, someone who made low budget features with foreign markets, international film festivals and awards in mind. The more discriminating marvel at Ray’s genius and call him the last titan of the nineteenth century Bengal renaissance. On the other hand, to the post-colonial theorists, Ray is a modernist in the European sense and whose work, after all is said and done, is not really as Indian as Bollywood. A proper appraisal of Ray’s cinema and his luminous legacy is still in order.

In 1950, Satyajit Ray was asked by a major Calcutta publisher to illustrate a children’s edition of Pather Panchali, Bibhuti Bhushan Banerjee’s semi-autobiographical novel. On his way back from London, with little to do on a two-week boat journey, Ray ended up sketching the entire book. These formed the kernel and the essential visual elements in the making of Pather Panchali, Ray’s very first film and the one that brought him instant international recognition and fame.

At the 1956 Cannes Film Festival, Ray received in absentia the Best Human Document Award for this hauntingly beautiful film with its carefully executed details of the joys and sorrows in the life of a little boy named Apu in a tiny village in Bengal during the 1920s. Instant fame, however, did not bring in its wake, instant fortune.

During his life and filmmaking career, Ray received many honours. In addition to the Honorary Academy Award for Lifetime Achievement, which he received in 1992 in his hospital room a few weeks before he passed away, he was also presented with the Bharat Ratna, India’s highest civilian honour. Oxford University conferred on him an honorary doctorate; the University of California, Berkeley, awarded him the Berkeley Medal. In 1989, President François Mitterrand of France went to Kolkata (Calcutta) to personally award him the Légion d’honneur.

INDIA IN RAY’S VISION

One can identify three major compositional periods in Ray’s life. The first period (1955-1964) was remarkable for its robust optimism, celebration of the human spirit and creative satisfaction. Ray was not only directing and scripting, but also scoring the music and taking charge of the cinematography. During this period, he directed, arguably, his greatest films. This period coincided with India’s early years of independence and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s experiments with secular democracy based on humanism, internationalism and modernism.

The second period (1965-1977) saw India come under a dark spell. There was war with China (1962) during Nehru’s last years, followed by a war with Pakistan (1965). Growing urban unemployment and an agricultural crisis brought about by a command economy created near-famine conditions in various parts of the country. The Vietnam War and the Cultural Revolution in China had radicalised Kolkata’s youths, artists, writers and intellectuals. Revolutionary and counterrevolutionary violence gripped the city. Kolkata, once known as a friendly and safe city, became a dangerous place to live. The Bangladesh War (1971) caused an influx of millions of refugees fleeing the Pakistani army, filling Kolkata and its outskirts. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, battling massive opposition to her government, imposed “Emergency” rule on the country. India came under draconian control, but there were few signs of serious protests: people followed orders, the streets looked cleaner, the economy showed growth, and the trains were running on time.

Ray was troubled. The films he made during this period clearly projected a troubled vision of India. The Calcutta Trilogy: The Adversary (1970), Company Limited (1971), and The Middleman (1975) created powerful portraits of alienation, waywardness, and moral collapse. Days and Nights in the Forest (1969) and Distant Thunder (1973), made during the Bangladesh War on the subject of the Bengal famine of 1943, showed rape and violence in a straightforward manner. The Chess Players,(1977) made during the “Emergency,” used the metaphor of a chess game to show how the king of Oudh, more a poet and composer than a ruler, submitted to the British takeover of his kingdom in 1856 as his people fled their villages. The two short films Pikoo (1981) and Deliverance (1981) raised the issues of adultery and untouchability. Even his so-called escapist films – the Goopy and Bagha (1968) musicals and the detective lm Golden Fortress (1974) – carried messages against wars, criminality and greed. In midlife, at the height of his creative powers, Ray seemed to have adopted a dark worldview. Socially, he became increasingly isolated.

In the third and last phase (1977-1992), Ray’s worldview came full circle. In the 1980s he became even more isolated and distant. In the films he made during this period, he related his messages in definitive terms. Unlike his early work, his films became didactic and frank. Gone were the carefully crafted shades of grey. Home and the World (1984), based on a Rabindranath Tagore novel, is a diatribe against nationalism, the mix of religion and politics, and political opportunism and dishonesty. Although the theme is the Swadeshi movement1 of 1905, Home and the World addressed issues of critical concern in the 1980s.

Stricken by two heart attacks, Ray was not able to make films with his characteristic vigour. He made modest family dramas, shot indoors under the watchful eyes of his doctors. He made three films, all based on his own stories, in 1988, 1989 and 1990. The first, Enemy of the People (1988), an adaptation of the Henrik Ibsen play to Bengali language, addressed questions of capitalist corruption and manipulation of religion, people, politics and environment. Branches of a Tree (1989) also addressed issues of capitalism as it impacts family values and ethics. The protagonist, a heart patient like Ray, is obsessed with honesty, mediated by mood swings of music and madness. The third film, The Stranger (1990), literally carries Ray’s own voice as he sings in parts of the film. The protagonist is clearly Ray himself. His global concerns are articulated locally. Who is an artist? Who is civilised and who is primitive? The protagonist is against narrowness of all sorts, against boundaries and borders. “Don’t be a frog in the well,” he tells his grandnephew as the film comes to an end.

Ray was a product of the Anglo-Bengali encounter of the nineteenth century. His cultural, intellectual and ideological roots can be traced to what is known as the “Bengali Renaissance.” The Bengali Renaissance refers to the flowering of Bengali arts and culture in the 19th century. As a powerfully creative artist, his craft was influenced as much by the West as by the Bengal School. One can argue that, in the final analysis, he was more than a product of the “Calcutta modern” – a synthesis of the East and the West. His creativity, he once remarked, remained grounded both in what is uniquely Bengali and in what is universal.

THE ART OF RAY

Let us try to situate Satyajit Ray in his art. Our primary concern here is with his creativity – the process of creation and the person. Aristotle defined the principle of creation as nous poietikos, the poetic reason. It is a principle that can apply to the creation of the universe itself – the creative act brought into existence something that did not exist before. A human artist, by definition, cannot produce what the Great Creator has done, and produce something out of nothing. The human act of creation always involves a reshaping of given material, whether physical or mental. What are the objective conditions of this given material and its reconstitution in creative work? Philosopher Thomas Nagel has argued that objectivity cannot be studied in just Universalist terms, what he terms a view from “nowhere”. It must be identified with a positional perspective, a view from “somewhere”. In Satyajit Ray’s work, there is a creative dialogue between what is universal and what is unique to his objective conditions, between the global and the local.

MUSIC

Music is another profound and uniquely personal aspect to Ray’s film art. He said while making films he thought musically – all his film narratives are structured like sonatas.

I argue that Ray, like Tagore, was a modern innovator in revolutionising Indian music. The challenge to Ray came from the music he needed for his films. He relied at first on great musicians like Ravi Shankar, Vilayat Khan or Ali Akbar Khan. However, he was dissatisfied and started to score his own music. Here he was at his innovative best, first in Charulata, and then in his Goopy & Bagha adventure films.

What kind of music did Ray compose? To what extent is it based on the traditions of India and Europe? What about his poster designs, drawings and costume sketches, book jackets, calligraphy and illustrations? And finally, what about his films?

What in the final analysis emerged in all of Ray’s art is his own agency and the originality of his creation. Looking at his designs, graphics, and posters one finds a grand artist assured in the practice of his media and using it deftly to realise the idea and intent. His music has a playful melodic geometry, reduced to the barest essentials, with a focus usually on one or two timbres. The flute presents a series of apeggiated phrases forming a musical signature of its own. One can say the same thing about his films: they show a radical simplicity, concealing layer upon layer of ingenuity and complex composition. These defy all labels, and the only one that seems apt and appropriate is Ray’s own unique signature in all his work.

When an interviewer addressed Akira Kurosawa “the master”, he responded by saying “Not me. Ray is the master. Not to have seen his films is like living on earth and not seeing the Sun and the Moon.”

About the writer: A consultant for the Satyajit Ray Retrospective organised by the National Museum of Singapore, Dilip K. Basu has established a world class Archive and Study Center on Satyajit Ray (Ray FASC), and an innovative, culturally focused South Asia Studies Center at University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC). With the cooperation of the Ray FASC at UCSC and the Ray Society in Calcutta, Basu coordinates the restoration and preservation of Ray’s films. The work is done at the Academy of Motion Pictures Archives in Los Angeles. To date in 2010, out of Ray’s 37- film oeuvre, 22 have been fully restored.