Text by Joshua Goh

Student Contribution

MuseSG Volume 10 Issue 1 - June 2017

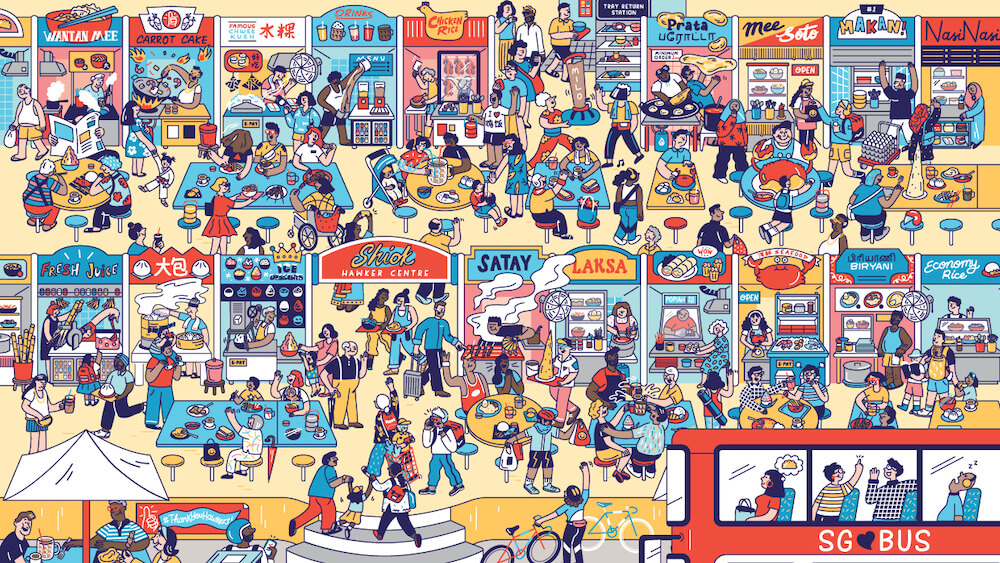

Step into any Ya Kun Kaya Toast or Toast Box outlet island-wide, and you may find yourself being transported to another era. With vintage décor and sepia-toned photographs adorning their walls, these boutique kopi (Malay for “coffee”) joints are not just places for diners to savour familiar, comfort food. They are also sites where the history and heritage surrounding local food is prominently displayed. Diners munching on crisp kaya (Malay for “coconut jam”) toast are thus invited to experience the coffee shop of the 1960s, which has been designed to invoke the feeling of a simple, laidback oasis where patrons can come to unwind. As the Toast Box website suggests, the coffee shop of the sixties “was reinvented to bring back fond memories for those who missed the good old times, and for the younger ones to experience the feel and flavours of a bygone era”.

Besides their portrayal of the 1960s coffee shop as an idyllic space, such kopi joints also suggest that coffee shops were largely defined by their Chinese ownership. Valorised are the stories of early Hainanese coffee shop proprietors, who by the dint of hard work built up thriving family businesses.

The central persona in Ya Kun’s narrative, for example, is Loi Ah Koon. Hailed as a simple man who first started his business with a coffee stall in Telok Ayer, Loi’s rags-to-riches story graces the walls of all Ya Kun outlets. With competitor chains such as Kiliney Kopitiam also constructing a similar narrative of Chinese ingenuity and industry, it is no surprise that the coffee shop’s past has come to be defined by the contributions of Chinese migrants who, it seems, set up shops merely for eating and socialising at a leisurely pace.

Nevertheless, such a historical imagination of the 1960s coffee shop – as a rustic eatery defined by its Chinese roots – deserves to be explored further. This is because such a static conception of the coffee shop seems to be out of joint with the dynamism of Singapore’s society in the sixties. Indeed, this was an age of cultural ferment, during which the everyday lives of Singapore’s residents were shaped by a vibrant cosmopolitan modernity. As the term “swinging sixties” suggest, modernity in this period was closely associated with youth-based, Western cultural fads such as the The Beatles, who used new forms of technology such as multi-track recording to create higher quality records to market their music to a global crowd. Popular artistic forms catering to mass audiences were all the rage, particularly in Singapore, where local bands such as The Quests and The Silver Strings drew on influences of an international import to synthesise new strands of consumptive entertainment. To be modern, thus, was to be in sync with popular trends that integrated both Western and local elements, and to be engaged with a dynamic cultural world that was diverse and eclectic.

As an alternative “third space” away from both home and work, it is rather inconceivable that coffee shops were merely tranquil arenas, isolated from the lively cultural verve of the day. Oral history interviews and newspaper articles from that era reveal, indeed, that there was much more to the 1960s coffee shop than kaya and toast.

These sources also suggest that focussing on the Hainanese kopitiam (a mixed Malay-Hokkien term for “coffee shop”) alone is insufficient. Rather, one must also examine the worlds of the Malay kedaikopi (Malay for “coffee shop”) and Indian teh sarabat (a colloquial Singaporean term for “milk tea”) stall, for all were equally dynamic spaces that constituted part of Singapore’s public sphere in the sixties. As sites for the congregation of multiracial patrons, coffee shops of the 1960s were not only the domain of the Chinese community as we often imagine them to be. In fact, the multiracialism of the 1960s coffee shop went well beyond vernacular forms. As sites frequented by a globally cosmopolitan clientele, coffee shops were part and parcel of a flourishing cultural scene that produced a vibrant, popular modernity.

In 1960s Singapore, coffee shops that catered to patrons beyond the typical Chinese, Malay or Indian customer could be found all across the island. One notable site was the teh sarabat stall cluster outside Rex Cinema, where patrons as diverse as Eurasian and Jewish folk could be found mingling.

Syed Alwi Road in the Rochor district was also another prominent locale where coffee shops played host to clienteles of a global nature. Mohd Buang bin Marzuki, a recruiter for a Malay bangsawan (a type of traditional Malay opera) troupe, even likened one particular coffee shop along Syed Alwi Road to a port, with aspiring bangsawan performers from as far as Manila congregating to seek artistic employment.

However, the globally diverse patrons that weaved in and out of the Syed Alwi Road coffee shop were merely part of a bigger picture. This is because the cosmopolitanism of the Syed Alwi Road coffee shop was linked to new forms of consumptive entertainment that were popularised by three ”worlds” of mid-twentieth century Singapore. In the sixties, three amusement parks – Happy World in Geylang, New World in Jalan Besar and Great World in River Valley – were at the forefront of popular entertainment in Singapore, with performances infused by a syncretic, East-meets-West flavour. Yet they had an unexplored connection to the coffee shop, for travelling troupes performing in the “worlds” would often head out from the Syed Alwi Road coffee shop and return again past midnight to rest before heading home at three or four in the morning. There was even a billiard table at the coffee shop over which the bangsawan performers, comedians and musicians of the travelling troupes would bond. After the Syed Alwi Road coffee shop was closed, another coffee shop at the intersection of Geylang Road and Joo Chiat Road took over this function.

Apart from the coffee shop’s links with the three “worlds”, new pop-culture forms that emanated from the confines of the 1960s coffee shop also demonstrate how closely intertwined it was with a cosmopolitan and outward looking society. One advertisement placed in the Singapore Free Press on 21 November, 1961 by a local band called The Rhythmnaires bears testament to this. Billed as “one of the top Latin rhythm bands in the district”, the band’s lead musician, Mr Earl da Silva, called for a girl to join the eight-man team, while proudly highlighting the fact that the band was formed at “a coffee shop meeting of eight music crazy young men”.

Oral history interviews with prominent musicians of the 1960s further confirm that coffee shops were favoured as meeting sites for members of Western-style rock-and- roll bands. Particular appealing, it seems, was the convivial atmosphere surrounding Indian teh sarabat stalls, which were a distinctive feature of Singapore’s food-scape of that period. In the 1960s, prominent clusters of teh sarabat stalls could be found near present-day Newton Hawker Centre, Cathay Cinema and along Albert Street. For local bands such as The Checkmates that dominated this golden age of local music, such stalls provided spirited spaces that were inherently conducive to the new, modern forms of music that they sought to popularise. At teh sarabat stalls such as the one near Golden Venus bar, musicians such as Henry Suriya, a member of The Boys, could be found chatting and gossiping about the local music scene into the wee hours of the morning. The 4th mile teh sarabat stall in Bukit Timah was also popular, for it brought together musicians and university students from the nearby Dunearn Hostels. Long before 24-hour fast-food restaurants made its way to Singapore’s shores, teh sarabat stalls were already catering to nocturnal youths, who represented a restless, pulsating society, eager to experiment with novel cultural forms.

Besides Western-style music, other mass cultural forms of a popular nature were also birthed from within the coffee shop. Activities performed in and around coffee shops thus provided a good barometer of the rapidly changing tastes of a modern, cosmopolitan society, as hobbyists of new artistic forms gathered to further their craft. One such art form was photography. The Photographic Society of Singapore, for instance, was conceived as the Singapore Camera Club in 1950 by a group of seven men who met in a coffee shop. Picture records from the National Archives of Singapore reveal that this was not a one-off phenomenon. A photo from 1962 (see below) shows evidence of a crowded coffee shop brimming with photography enthusiasts with cameras slung around their necks.

Lastly, the creation of new culinary forms also testified to the coffee shop's role in synthesising various cultures and creeds. According to Vernon Cornelius, the popular Singaporean snack, Roti John (consisting of a French loaf topped with eggs and onions), was birthed when the English submarine sandwich was adapted by teh sarabat stalls operating along Changi Point to cater to British soldiers stationed in the vicinity. Retaining the practice of cutting up a large French loaf into manageable portions, Indian teh sarabat stall proprietors proceeded to give quintessential British fare a cosmopolitan twist by infusing fried eggs and tomato sauce. As stall owners hollered “hey, roti (Malay for “bread”) – John!” as a generic and colloquial reference to the passing European customer, the term gained social currency as a reference to a scrumptious new snack.

To conclude, it is clear that contemporary historical perceptions of the coffee shop as an idyllic, Chinese-populated space merely serving up delectable kaya toast are rather restrictive. The story of the 1960s coffee shop is not only confined to the Hainanese kopitiam, but is part of a larger coffee shop world that was shared equally by its Malay and Indian counterparts. Varied as they were outwardly, together they jointly inhabited a shared social space – one defined by a diverse, cosmopolitan identity. is cosmopolitanism, in turn, ensured that coffee shops in the 1960s were not merely spaces for gustatory consumption. Rather, they had an equally important function as sites of cultural fermentation and experimentation as Singaporeans-to-be grappled with, and embraced, a new popular modernity.