Text by Ruchi Mittal

MuseSG Volume 9 Issue 2 - Apr to Jun 2016

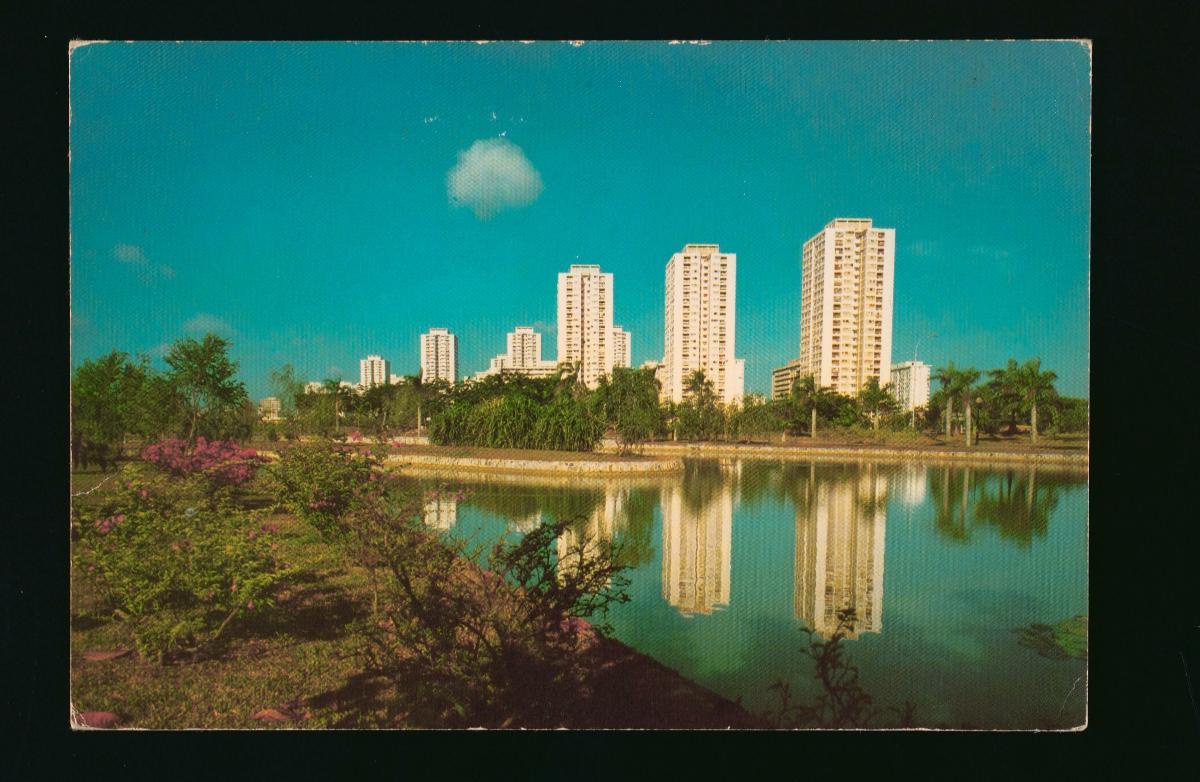

Sun, sand and palm trees have long defined Singapore's eastern coast. Before the extensive land reclamation project that began in the 1960s, the seashore was right outside many of the houses still seen today, including the popular Hua Yu Wee restaurant, which retains its original steps that used to lead to the beach.

The East Coast of the first half of the twentieth century was what we now know as Bedok and its surrounding areas. Singapore Memory Project contributor Bernard Han shares: “Before Marine Parade was reclaimed, the beach used to be along Marine Parade Road, just behind the courtyard of the Grand Hotel – a place where children could really grow up by the sea.”

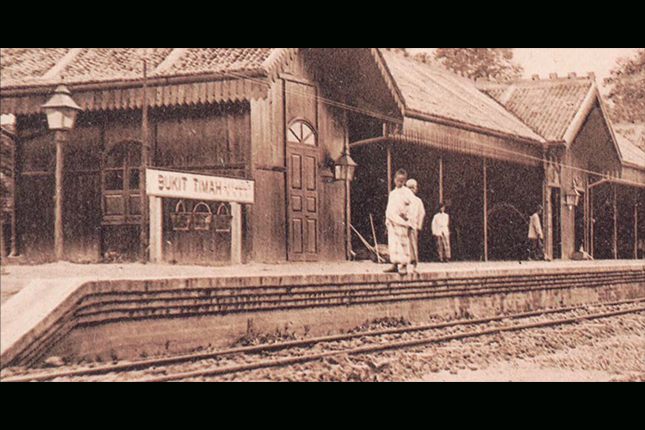

Bedok was one of the earliest documented places in Singapore, as seen from a 1604 map referring to Sungei Bedok (Bedok River) as Sunebodo.

As to how the name came about, one view is that it derives from the Malay word bedoh, a wooden drum formerly used to issue the Islamic call to prayer. Another links Bedok to the word biduk, a riverine fishing boat.

Bedok grew around the river and the coast as a series of villages. Each village had its own unique story. Chai Chee’s name refers in Hokkien to a vegetable market, which is what it first began as. Heritage blogger Yeo Hong Eng remembers: “As soon as we moved there, acquaintances were forged. There was the fishmonger, Mr Lee Tng, from Chai Chee market... His well constantly supplied the neighbours with cool refreshing water. He invited us to use his well water which we did until we got portable pipe water.”

Kampong Bedok was situated at the crossroads of Bedok Road and Upper East Coast Road and is an area still affectionately known as Bedok Corner. Ronald Ho, who was born there, shares his memories: “It was the best days of my life living in Bedok Village... we owned nothing of luxury but we led a most colourful childhood. From climbing trees searching for fruits to attempting to swim in the sand mines at Koh Sek Lim Road, our afternoons were never lonely or dull.”

Bedok of the past included Siglap, which also comes from the Malay word si-gelap (“dark one”), likely refering to either an eclipse at the time of its founding or the thick canopy of coconut trees in the area. The village’s founder was Tok Lasam, believed to be an Indonesian royal fleeing from the Dutch. Today his tombstone is located in Siglap. Mrs Rita Fernando speaks of her experiences living in the village: “For us, I would say there really was no difference in race. We did not even think of ourselves as Singaporeans then, because we were just emerging from colonial rule. We just lived as kampong people and neighbours and we shared whatever we had.”

Tanah Merah, also part of the larger Bedok in the past, literally means “red cliffs” in Malay, referring to the seaside cliffs of reddish clay-like soil that characterised the area. Heritage blogger Jerome Lim reflects: “Marked by a landscape that would seem out of place in the Singapore of today with its terrain that undulated with cliffs that overlooked the sea, the area was decorated with gorgeous seaside villas and attap-roofed wooden huts of coastal villages that provided a laidback feel to the surroundings...” In stark contrast, the Tanah Merah area was also fortified with artillery guns and pillboxes from which soldiers could shoot enemies approaching from the sea.

Surviving fragments of old seawalls tell of the evolution of the east’s character and physical landscape. Two of these seawalls can be found behind Elliot Walk and along Nallur Road today, indicating the former coastline. As Bedok was close to the sea, it was not surprising that many made their living from this water- side advantage. Fishermen would haul their catch of local fish such as scad, wolf herring and mackerel from the shore to Siglap Market for sale. Others toiled the land, farming tapioca, vegetables, and collecting coconut and nipah palms. Harvests were then transported via old Changi Road to nearby Chai Chee for sale.

Along these low-lying areas, floods however were a frequent occurrence. Former Siglap resident Felicia Goh shares: “Whenever there were heavy showers, we would have to watch out for floods and bring our furniture to the second floor. It was fun for us kids as we could play water officially!”

Fire, too, did not spare these areas. In a 1962 blaze, 500 Siglap residents saw their kampong ravaged by flames on Chinese New Year’s day – the result of firecrackers landing on flammable attap roofs. Long-time resident Goh Chiang Siang shared that affected families had to be resettled to temporary housing nearby. Former bank officer Aloysius Leo De Conceicao also recalled how the neighbouring kampongs united to put out the fire: “I remember everybody from the neighbourhood came out to help the fire brigade and firemen because they had a bit of difficulty getting the water. It was sad because it was during the festive season.”

Seaside and water activities were part of the area’s recreational highlights. Bedok Beach (the coastal stretch from Upper East Coast Road to Bedok Corner) was the site of holiday accommodations and restaurants. This lifestyle was enjoyed by residents and visitors from across the island and even overseas, who visited the beach for picnics, recreational fishing, swimming and kolek (small wooden boat of regional origin) racing. Dance parties by the beach were said to have been organised for all to enjoy. Writing in The Straits Times in 1978, T. F. Hwang shares: “I remember the early 1950s where the annual Bedok-Siglap boat races were major pesta [“carnival” in Malay] events, culminating at the end of the day in Bedok with community joget [a dance of Malaccan origin], dancing under coconut trees by the sandy beach.”

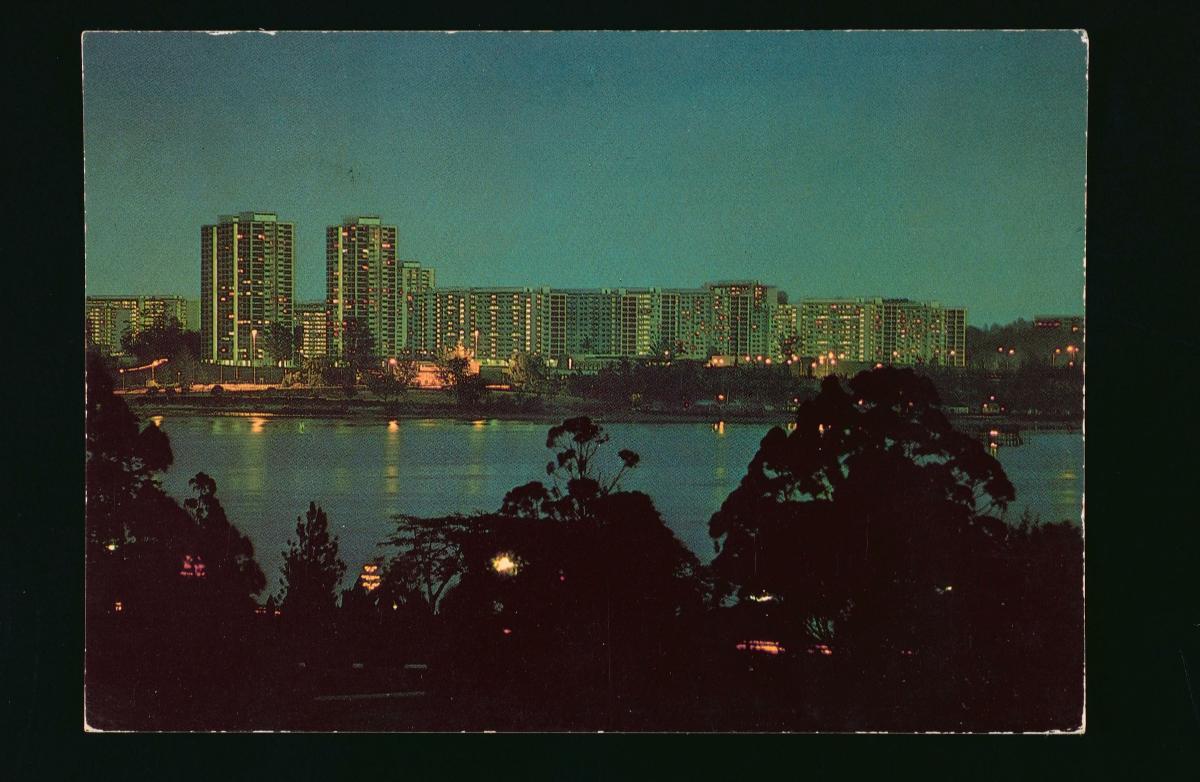

In the 1960s, land scarcity prompted the government to embark on major land reclamation exercises. The extensive East Coast Reclamation Scheme, which commenced in 1966, was undertaken by the Housing & Development Board (HDB) as its largest venture at that time. Hills at Siglap, Bedok and Tampines were levelled using fully mechanised bucket wheel excavators and an automated conveyer belt transported the sand to the reclamation site. This project eventually added 1,525 hectares of land stretching from Bedok to Tanjong Rhu. It aimed to combine high density housing development with commercial and industrial interests in one area.

By the 1970s, kampongs began to make way for modern flats and industrial parks, and villagers were offered new flats in surrounding areas. At the time, Chai Chee was the only urban residential estate in the otherwise still rural, eastern region of Singapore. Mah Eng Siong, one of Chai Chee’s first residents, recalls: “By then, our family house (in the kampong) was very crowded. There were a lot of problems with so many people living so close together. It felt good to move to my own house.”

Completed in the early 1980s, Bedok New Town was one of the new generation HDB towns that was planned as a total living environment. Residents, largely former farmers and fishermen, were also able to find new employment with big industrial companies like Matsushita, Hitachi and Fuji, whose factories were located in the area. Bedok’s connectivity with the rest of Singapore increased with the completion of the 36-kilometre Pan-Island Expressway (PIE) in 1980 linking both ends of the island.

Bedok resident Keith Tan remembers moving into a high-rise at in Bedok South: “When we first moved, I was excited – you get to see such a nice view over the east coast.” Resident Mahat Bin Ariffin, also appreciated the comforts of the new flats: “It’s a most convenient town, particularly for me because I work at the airport... You can really get a good night’s sleep here. There are no mosquitoes!”

While older residents recall the kampong days, the younger generation has fond memories of the stretch of East Coast created through land reclamation. Singapore Memory Project contributor Cassandra Lee recounts: “To me, my neighbourhood constitutes of ECP (East Coast Park) because the route towards it holds a very special place in my heart. I will always remember my cycling trips with my dad... On those weekly Sunday trips, I would cycle behind my dad, taking in all the sights and sounds from our house to ECP. Sometimes, we would cycle as far as we could, until we were exhausted. It was fun and a great adventure for a kid.”

Development of the area continues, with HDB’s Remaking Our Heartlands (ROH) project that has once again transformed the Bedok town centre through an integrated complex, redeveloped hawker centre, sporting facilities, and a town plaza that includes a heritage corner supported by the National Heritage Board.

If you are keen to discover more about Bedok and the East Coast's rich heritage, set out on the Bedok Heritage Trail. Download the trail booklet and map here. Enjoy your adventure!