A stellar student

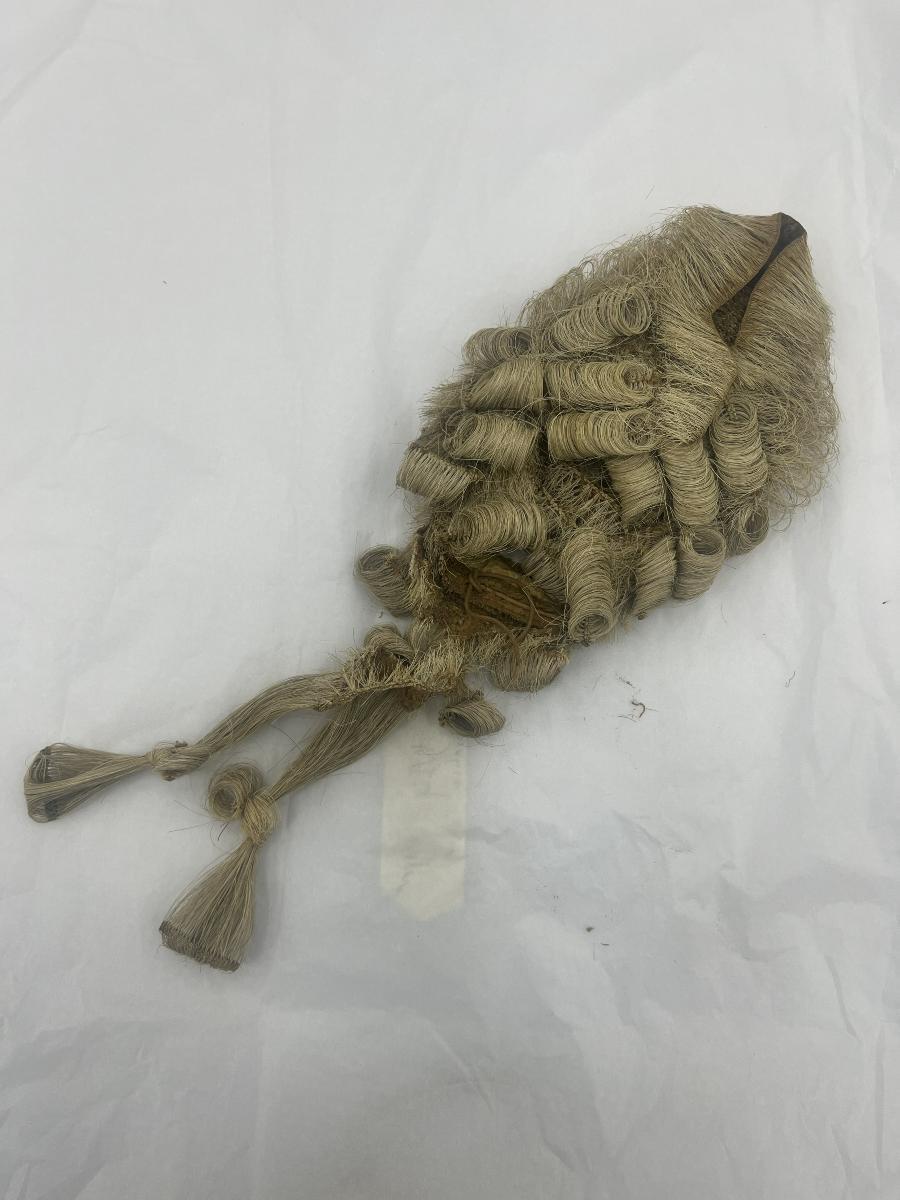

Ahmad Ibrahim was intellectually ambitious from a young age, graduating from prestigious institutions such as Victoria Bridge School, Raffles Institution and Raffles College. In 1936, he was awarded the Queen’s Scholarship to study at Cambridge University, passing the bar exams in London in 1940. While there, Ahmad even picked up the George Long Prize for Roman Law.1

Underlying Ahmad's cerebral gifts was a deep passion for the Malay Muslim community. His father, a medical practitioner active in Islamic social and welfare activities, could have had some bearing on this.2

Upon graduation, Ahmad would work to improve the community's status during the Republic of Singapore’s formative years through activism, scholarly contributions, and his eventual role as a lawmaker. He was called to the bar in Singapore in 1941.

A prolific career

Ahmad rose quickly in the legal scene, despite disruptions in the early days of his career due to World War II. After three years in the civil service as a magistrate then district judge, he chalked up experience in private practice and as a law lecturer, before returning as deputy public prosecutor and senior crown counsel.

In and around 1949, Ahmad drafted the constitution of the Inter-religious Organisation which was established to maintain interfaith harmony. He was also one of its founding members.3 Just a year later, racial and religious riots broke out as a result of the heated Maria/Nadra Hertogh custody battle. In declaring her Islamic marriage illegal, Singapore’s High Court drew the ire of members of the Muslim community.4 Ahmad had represented the man she was married to in a nikah gantung or truncated marriage.5

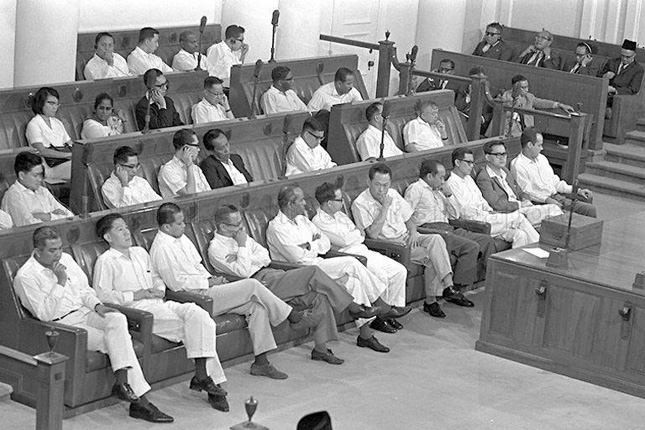

From 1959 to 1965, Ahmad took his seat as Singapore's first ever state advocate general, having been picked by merit for his intellect.6 He weighed in on critical merger talks with Malaysia.

State advocate-general Ahmad Ibrahim in 1962. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

State advocate-general Ahmad Ibrahim in 1962. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

The installation of Yang di-Pertuan Negara Yusof Ishak on 3 December 1959 in the presence of chief justice Sir Alan Rose, as witnessed by state advocate-general Ahmad Ibrahim (far right) at the City Hall Chambers alongside prime minister Lee Kuan Yew and speaker of the legislative assembly Sir George Oehlers. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

The installation of Yang di-Pertuan Negara Yusof Ishak on 3 December 1959 in the presence of chief justice Sir Alan Rose, as witnessed by state advocate-general Ahmad Ibrahim (far right) at the City Hall Chambers alongside prime minister Lee Kuan Yew and speaker of the legislative assembly Sir George Oehlers. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

Ahmad Ibrahim’s brilliant mind was tapped for a variety of legal issues including merger with Malaysia. This is a voting card for the referendum of merger on 1 September 1962. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Ahmad Ibrahim’s brilliant mind was tapped for a variety of legal issues including merger with Malaysia. This is a voting card for the referendum of merger on 1 September 1962. (Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

The Battle for Merger by Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew. (Image from National Museum of Singapore.)

The Battle for Merger by Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew. (Image from National Museum of Singapore.)

Upon Singapore’s independence, Ahmad became Singapore’s first attorney-general. His legal mind was tapped by the law fraternity and government on a range of legal issues in administrative, property, finance and contract law. He was also involved in the drafting of the Women’s Charter, Intestate Succession Act, and other statutes that serve as the basis for Singapore’s legal system today.7

All this while, Ahmad, eager to improve the legal status of his community, studied Malay Muslim law avidly. He delved into the archives and produced extensive research on the legal history of Muslims in Southeast Asia, examining and comparing how Muslim law was administered historically in Malay states and in other countries in the region where it was not traditionally in practice.8

With such a depth of knowledge, Ahmad was the best man to formulate and draft the Administration of Muslim Law Act (AMLA) for Singapore — a task he poured his heart into. In advocating for Muslim laws to be folded into Singapore’s legal framework, he valued and respected convention. However, he refused to allow tradition to get in the way of progress for the community. As such, he kept a keen eye on issues of equality as well as the protection of the vulnerable.

AMLA, which came into effect in 1968, deals with marriage and divorce matters, and also led to the establishment of Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura (MUIS). Muis, the Islamic religious council, guides the Muslim community and administers zakat (tithe), wakaf (endowment), pilgrimage affairs and the like.

Ahmad Ibrahim (right) receiving a cheque from a Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura representative on behalf of a mosque. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

Ahmad Ibrahim (right) receiving a cheque from a Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura representative on behalf of a mosque. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

AMLA stands as a piece of outstanding, landmark legislation given that Singapore is the only former British colony with a minority Muslim population to have such a law, and the only one with an Islamic religious council integrated within the state’s legal structure.

Attesting to Ahmad’s legal prowess, pioneer leader Goh Keng Swee described him as a man of “tremendous breadth and depth of intellect, whose ability as a legal draftsman is unsurpassed in this country".9

Powerhouse of a professor

The last chapter of Ahmad's career was spent in academia. He moved to Malaysia and helped establish the country’s first law faculty at the University of Malaya in 1972.

Not one to rest on his laurels, Ahmad moved around the country meeting leaders and administrators of Muslim law to keep abreast of issues. In his golden years, he continued to be in demand and worked the international conferences’ and seminars’ circuit.

He passed away from a heart attack in Malaysia on 17 April 1999 but his legacy lives on in the academic and legal papers — of which there are more than 200 — he wrote, as well as the laws he shaped.