TL;DR

This is the digital companion to the exhibition Urang Banjar: Heritage and Culture of the Banjar in Singapore, which focuses on the Banjar community - one of the smallest sub-ethnic Malay communities in Singapore. Members of the community are able to trace their lineage to traders, diamond merchants, businessmen and travellers who arrived in Singapore from South Kalimantan via overland routes in the Malay Peninsula or by sea from as early as the beginning of the 19th century. Navigate their journey through this selection of objects and multimedia content by scrolling down or clicking through the themes on the left.

‘Haram manyarah waja sampai kaputing’ is a basa Banjar idiom which translates as ‘let not the steel (of a blade) stop short until its very point’ and serves as an exhortation for Banjar to undertake all endeavours with determination, to do their best and not give up until their goals are achieved. Amongst the older generation of Banjar, this idiom is regarded as a quintessential trait of Banjarese culture.

The Banjar or urang Banjar (Banjar people) as they call themselves, are the smallest group that make up the Malay community in Singapore. Many of them are able to trace the journeys of their ancestors from South Kalimantan to Singapore from the late 19th to mid-20th centuries. The social memories as well as community and personal stories of the Banjar are collectively embedded in various sites across the Malay Archipelago, where small but significant Banjar communities have established their presence.

In Singapore, many Banjar strive to preserve Banjarese language and culture through various means despite homogenising forces brought on by urbanisation, modernisation and globalisation. Featuring ethnographic objects, community stories and treasured family belongings, this community co-created exhibition showcases the Banjar's strong sense of kinship, industry and history.

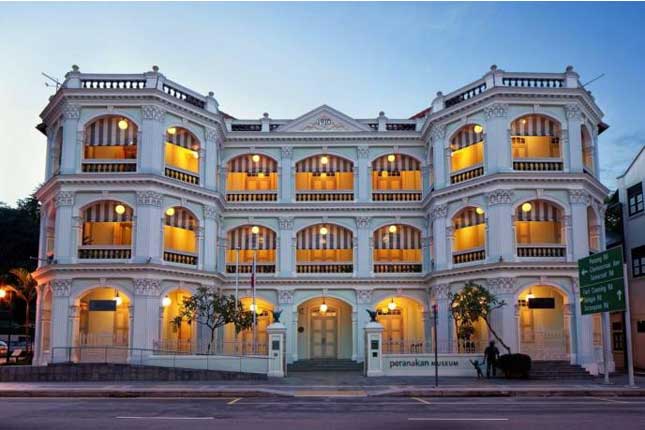

This digital exhibition is a supplement to ‘Urang Banjar’, a community co-created exhibition on display at the Malay Heritage Centre, and features select artefacts and multimedia from the exhibition. To experience the full exhibition, be sure to visit the Malay Heritage Centre from now until 25 July 2021 (visitor information can be found at https://malayheritage.org.sg).

The Banjar

An ethno-cultural group defines itself as a community when its members share a language, material culture as well as a set of cultural norms and practices. Oftentimes, the ethnic community claims a common history and can trace its people’s lineage to ancient or even mythical origins. In this respect, the families and individuals featured in this exhibition have come to identify themselves as Banjar through ‘cultural markers’ such as language, traditional dress, customs and cuisines as well as a shared history of ancestry from areas of the Banjar Regency in South Kalimantan.

Beyond a shared cultural heritage, many of the Banjar whose ancestors arrived in Singapore from the later half of the 19th century also associate themselves with a trading or religious family legacy. First and second-generation arrivals who settled in Singapore’s early precincts also developed deep connections to the kampungs and neighbourhoods they grew up in. This section introduces the individuals and families who worked closely with MHC to present their respective family histories and connections to areas in the Banjar Regency as well as offer insights into Banjarese culture as it is experienced and practised today.

“All of us are well aware that we are Malay but we don’t know which Malay ethnic group we come from. When I found out I was Banjarese… as I went along and listened to my dad and his side of the family, constantly talking about their memories, their relatives, majlis, perkahwinan (ceremonies and weddings), planned trips to Banjarmasin… this is where I realised this power of history through memory.”

- Syafiq Sahrom

From the Community

2020

Singapore

Malay Heritage Centre Collection, National Heritage Board

1 April 2000

Singapore

Collection of National Archives of Singapore

What Banjar delicacy are you?

The Banjar are known for their assortment of delectable dishes and desserts, including Soto Banjar and Kueh Bingka, which can be found across the Malay world. Sisters Fauziah and Maskiah, whose photograph can be found in the section below, used to sell some of these delicacies from their store, ‘Deli Maslina’, which continues to operate in Bedok today!

Consisting of a variety of ingredients, Banjar cuisine is well-suited for a range of palates and occasions. Find out more about these dishes through this interactive AR quiz!

Facebook: Click here

Instagram: Click here

Banjar Cosmopolitanism

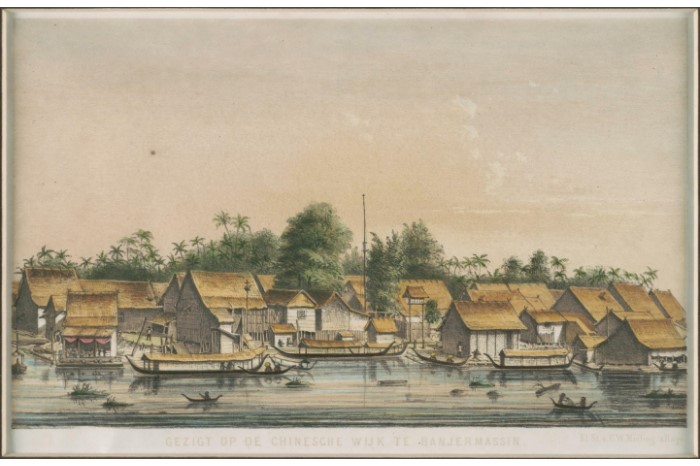

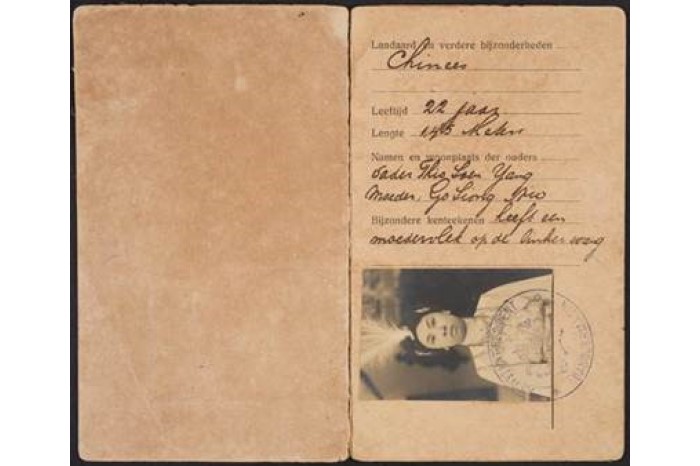

Till today, the urang Banjar in Singapore frequently mention the ways in which their ancestors in South Kalimantan and themselves were both a part, as well as a product of varied cultural influences in the region. In particular, South Kalimantan’s access to open waters and Banjarmasin’s natural resources created a thriving cosmopolitan marketplace visited by travellers from neighbouring cities such as Pontianak, Arab and Turkish traders as well as crewmen from Chinese junkships – from as far back as the 14th century.

This section showcases archival materials and other forms of material culture which illustrate how the mercantile Banjar world embraced cross-cultural influences and created a form of intercultural hybridity. Even as South Kalimantan’s status as a port city eventually succumbed to British and Dutch colonialism, the Banjar community would continue to interact with the outside world. These interactions took place not just within their increasingly thriving port, but also in the context of their migration out of South Kalimantan.

Watch: Video of the naga badudung being used in a 'naga berarak' ceremony as part of a wedding

2016Banjarmasin

Courtesy of Zhari Azhari

Known for its recurrence in Chinese culture, the naga (dragon) also appears in Banjar folklore as a symbol of the underworld. Such folklore often makes reference to two worlds - the land, symbolised by the enggang or rangkong gading i.e. the helmeted hornbill, now a mascot of South Kalimantan and the naga. The underworld is regarded to be the fortress of Putri Junjung Buih while the land is held by Pangeran Suryanata, the king responsible for the inception of the Banjar sultanate.

The naga badudung or badudus is a common feature of Banjar-made boats or perahu and has a few prominent characteristics, including a notably long neck and an agape mouth with a tongue sticking out. The presence of the figurehead is believed to ward off natural disasters from occurring during such regal occasions. In more modern practices, the naga figurehead appears on dragonboats and dragonboat events as well as wedding processions.

“O people of Negara-Dipa, lest you clothe yourself with the clothing of the Malays, or the Dutch, or the Chinese, or the Siamese, or the Aceh, or the Acehnese, or the Makassarese, or the Bugis, let us follow the ways of our own lands, following the customs of the Majapahit Empire. Thus our clothings shall follow that of the Javanese.”

– Hikayat Banjar

Religion and Reverence

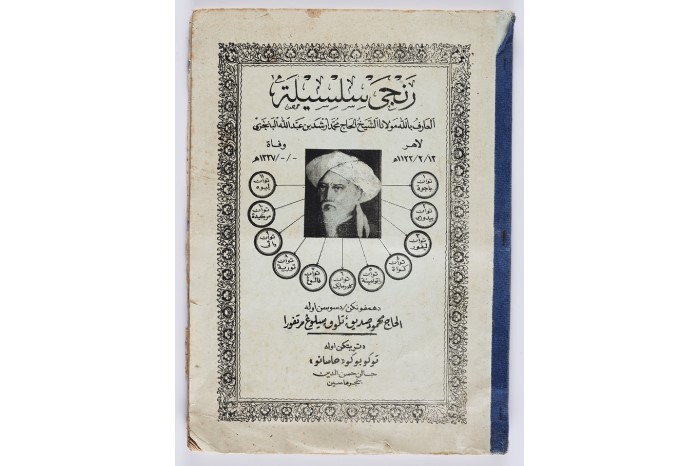

Some ethnographers have argued that the term ‘Banjar’ refers to a few binding elements that glue the disparate communities of South Kalimantan together rather than a specific ethnic group. One of these binding elements is Islam and its deep-seated importance in the Banjar community.

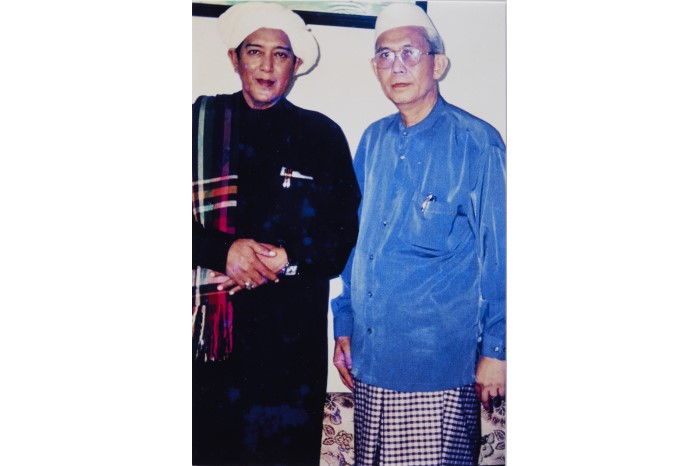

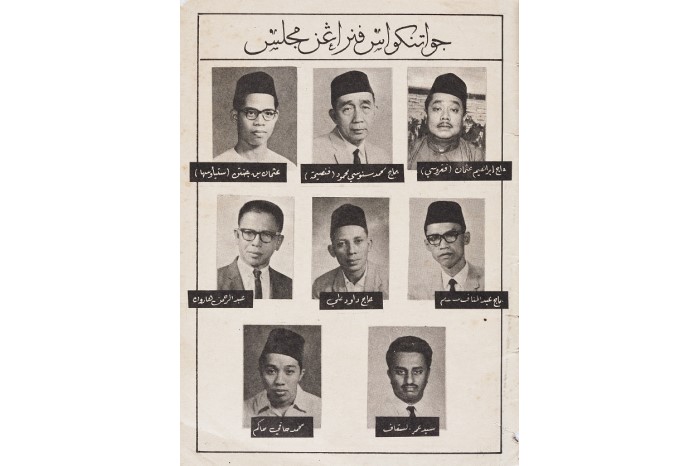

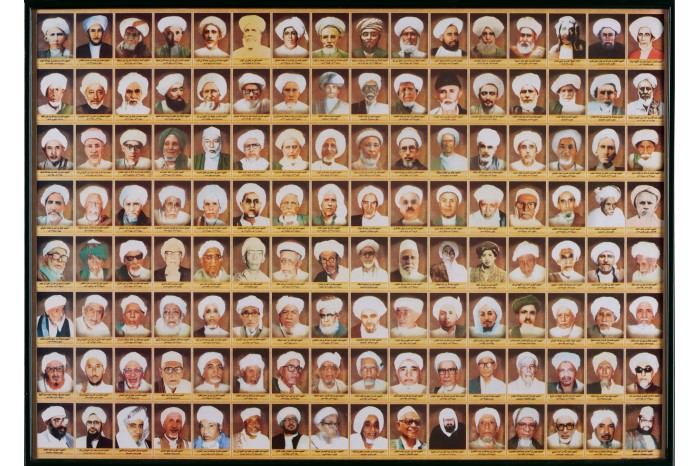

One way in which the Islamic aspect of Banjarese identity is manifested is through the reverence of prominent religious figures like Sheikh Arshad al-Banjari and Haji Mohamed Zaini Abdul Ghani (‘Guru Ijai’). In Singapore today, members of the Banjar community speak fondly of such religious Nusantara figures. Some Banjar have also participated in international religious events in Martapura, the birthplace of Sheikh Arshad al-Banjari and Guru Ijai.

Incidentally, Singapore’s first Mufti (a country’s chief Muslim cleric) Haji Mohamed Sanusi bin Mahmood is of Banjar descent, further reinforcing the importance of religion to the community. The following accounts and objects underline how religion is integral to Banjar identity and imagination, and how, beyond finding cultural significance, religion has also become a means to trace their roots back to South Kalimantan.

“In terms of religion, [the Banjar] are firm, ever since the arrival of Islam from the Demak Sultanate to Sultan Suriansyah who established the Banjar Sultanate which in turn propagated the religion of Islam. Thus, over there… the Muslim person truly adheres to the teachings of the religion, including, say, the buying and selling of items – so when one buys and sells, one buys and sells in accordance with religion.”

– Ustaz Miseran bin Rasidi

Watch: Reflections on Religion from the Urang Banjar

Interview with Ustaz Miseran bin Rasidi, Syafiq bin Sahrom and Gazali bin Arshad2020

Singapore

Collection of Malay Heritage Centre, National Heritage Board

In this video, various community members share with us the importance of their faith to their Banjar identity through stories of ancestors, and religious gatherings. This includes Ustaz Miseran, who arrived in Singapore in 2005 from Banjarmasin. He decided to settle here and married Cik Seniyati binte Mohamed Kassim, before eventually receiving his permanent residency in 2007. Since 1995, he has been a mutawif with Halijah Travel (a Singaporean-based pilgrimage company).

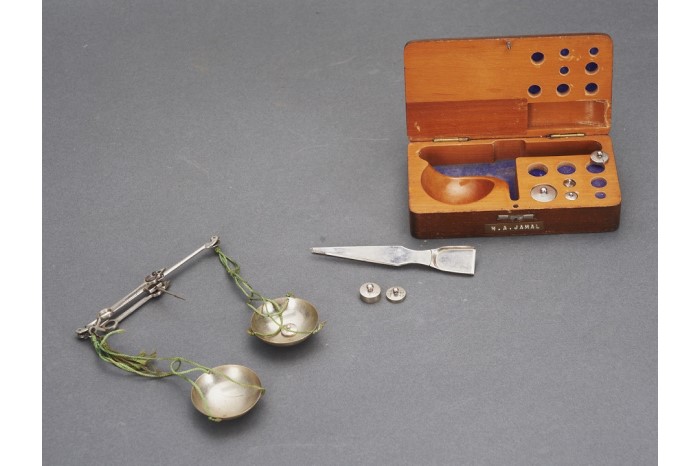

The Diamond Trade

Historically, the island of Borneo is famous for producing a wide range of precious stones and metals. While the Hikayat Banjar mentions “gold dust” as an important trade commodity, diamonds (mostly in the form of alluvial deposits along major rivers that cut across the western and southeastern parts of the island) are amongst South Kalimantan’s most precious exports. The diamond deposits of Borneo are said to be amongst the earliest mined by early Indians, Malays and Chinese who worked there as far back as 600-1000 CE. Evidence of diamond cutting is also found in the provinces of Ngabang and Pontianak in the southern parts of Borneo (present day Kalimantan).

These diamonds were not only bartered and worn by royalty and the rich, they were also included as part of tributary gifts from the Banjarmasin Sultanate to the Chinese emperor in the 17th century. By the 16th century, Borneo’s diamonds were known amongst Portuguese maritime traders and by mid-17th century, the Dutch East India Company established its monopoly over diamond mining and formed part of Banjarmasin’s global trade alongside pepper and other goods for the better part of the 19th to early 20th centuries.

This section provides the historical and socio-economic backdrop to the diamond trade and the mercantile roots of Banjar arrivals to Singapore in the 19th century. The riches gained from the diamond trade as well as the beauty of diamonds and diamond jewellery have led to the persistent association of the urang Banjar with diamonds.

“We had our neighbours – a goldsmithing workshop, an old Chinese man who would be working on these pieces of jewellery, mostly gold pieces, and then we had my uncle who’s working across the road… we had also another granduncle who had an office further down this road. Basically [Jalan Pisang] is where the activity of the diamond trade used to be.”

– Fauziah Jamal

From the Community

c. 1960s -1970s

Singapore

Courtesy of Faridah and Fauziah binte Jamal

Singapore

Collection of Malay Heritage Centre, National Heritage Board

South Kalimantan

Malay Heritage Centre Collection, National Heritage Board

Martapura is the largest diamond-cutting centre in Indonesia and is a bustling jewellery hub. Diamonds are regularly mined in Banjarbaru, located an hour away from Banjarmasin, before being transported to workshops which house several faceting and polishing machines. The faceting machines used here are also found in India. The machines have heavy bronze wheels attached by a spindle with bearings at the top and bottom, and a belt connects an electric motor to one to six cutting wheels. The round brilliant is the most common diamond cut here.

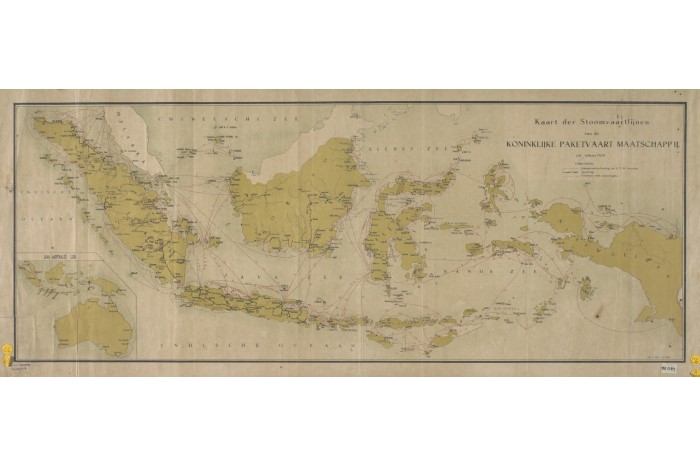

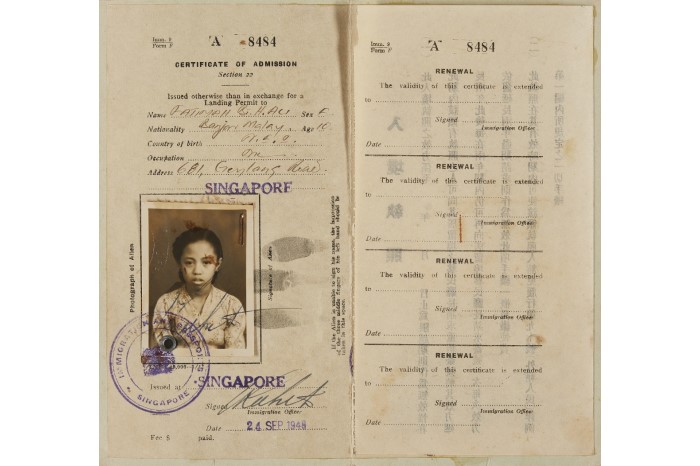

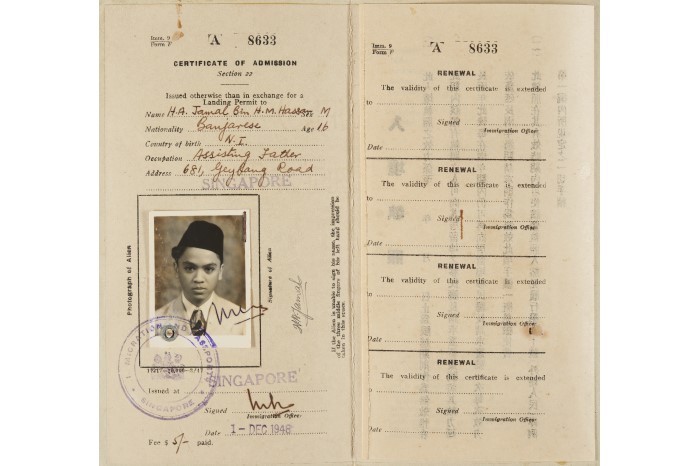

From Banjarmasin to Singapore

The 1911 Census of Singapore is the first local census that mentions the Banjar community and it notes that there were about 321 Singaporean Banjar residents during that period. However, if we were to refer to the oral histories of Singapore Banjar families as well as their personal photographs and news clippings, we would be able to trace their existence in Singapore to a far earlier time.

As far back as 1824, Dutch vessels from Banjarmasin began to arrive in Singapore when the former emerged out of decades of Dutch monopoly to become a free port. With this, traders from Banjarmasin like Haji Osman bin Haji Abu Naim and Haji Mahmood bin Abdul Rahim arrived in Singapore and became prominent fixtures within the local community due to their thriving businesses. By the late 1800s and early 1900s, several other Banjar families had begun to settle in Singapore. Driven from their hometowns in South Kalimantan as a result of the Banjarmasin War, these families were drawn to the prospect of peace that Singapore provided.

From the Community

c. 1940s – 1950s

Singapore

Courtesy of Faridah and Fauziah Jamal

Singapore

Malay Heritage Centre Collection, National Heritage Board

A Diamond Trail Across Singapores East

From the late 19th to the early 20th centuries, Banjar migrants settled down in various locales around Singapore. Diamond industry pioneers such as Haji Osman, Haji Mahmood and Haji Hassan established themselves in an area of Kampong Gelam which later became known as Jalan Intan, or Kampong Intan (today’s Baghdad Street). Located a stone’s throw from Kampong Intan was also a diamond polishing workshop owned by Banjar merchant Haji Hassan, located at Jalan Pisang along North Bridge Road.

Banjar communities could also be found eastwards near the shores of today’s Changi beach and East Coast Park as well as Kembangan and Geylang Serai. These sites were probably chosen by early Banjar settlers who fished for a living. They stayed in purpose-built rumah panggung (houses on stilts) in contrast to Banjar entrepreneurs in Kampong Gelam who stayed in shophouses.

Other sites in the eastern parts of Singapore where Banjar communities could be found include kampungs in Geylang (Lorong 26, 35, Lorong Engku Aman) and Changi (Kampong Banjar, Kampong Beting Kusah, Somapah, Telok Paku, Kampong Changi, Kampong Padang Terbakar) as well as today’s East Coast (Kampong Ayer Gemuroh, Telok Mata Ikan) and Eunos (Kampong Banjar, Jalan Keluang, Jalan Pagak).

“This house [at Lorong Marican] represented a house rich with history. That was where my uncles gathered in my youth, to speak to my father and reminisce about their father and grandfather. It was only much later that I realised that it was because of who my grandfather [Haji Mahmood] was.”

– Mohd Gazali bin Mohd Arshad

From the Community

Watch: Recordings of former residents of Banjar settlements speaking about their respective homes

Various datesSingapore

Reproduced with permission of National Archives of Singapore

Basa Banjar

Based on oral accounts, it can be determined that the language of the Banjar community, basa Banjar, remains an important identity marker across generations. Although many from the Banjar community in Singapore today do not converse in basa Banjar, the language provides the community with a sense of familiarity and sentimentality.

For the few urang Banjar who can converse in the language, basa Banjar is usually spoken in their households and during interactions with relatives from other places in the region such as Batu Pahat and Pontianak. In an attempt to keep the language alive, various members of the community launched a basa Banjar workshop initiative in 2014, where members of the community could attend classes taught by former Malay language teacher, Rasid Mastur. This language class is just one of the many ways where the Banjarese of today are re-discovering aspects of their heritage. Most importantly, these are done through physical interactions and the company of their fellow kinsfolk.“My aspirations for the coming generations of urang Banjar are that they would remember their culture, language, for it would not be good to forget one’s origins. In the words of a traditional Banjar slogan, haram manyarah waja sampai kaputing – whatever we do should be done well.”

– Mohd Gazali bin Mohd Arshad

Watch: ‘Being Banjar in Singapore’ featuring Ustaz Miseran bin Rasidi bin Tabdi

2020Singapore

Collection of Malay Heritage Centre, National Heritage Board

Arriving in Singapore from Banjarmasin, Martapura and Batu Pahat (another Banjar settlement) presented unique challenges for pioneer Banjar communities and individuals. Notably, speaking their native Banjar language had to take second place to learning and adapting to new vocabulary and lingo used in social, commercial and administrative settings in Singapore.

Watch: Video clip of a madihin performance

2020Singapore

Collection of Jorong Production

Basa Banja is not only functional, it also possesses a cultural role and is used in various performances as a way of communicating certain narratives and ideas. This is the case for madihin, an oral and aural performance that is infused with various social messages. Popular since the 1960s in South Kalimantan, madihin consists of oral recitations which are accompanied by the beat of the gendang, a drum-like instrument.

Madihin is usually performed at cultural events, such as the aruh ganal or festivities that promote traditional Banjarese identity. Derived from the Arabic word madah which means advice or in some instances, praise, the art of madihin has been known to reflect values such as tolerance, discipline, hard work, responsibility and patriotism. Hence, this literary performance has been used by the Banjar community to promote moral education, especially amongst the younger generation.

Watch: ‘Commemorating Basa Banjar in Singapore’ featuring Latiff Omar

Singapore

Collection of Malay Heritage Centre, National Heritage Board

Let's Practise!

Family Life

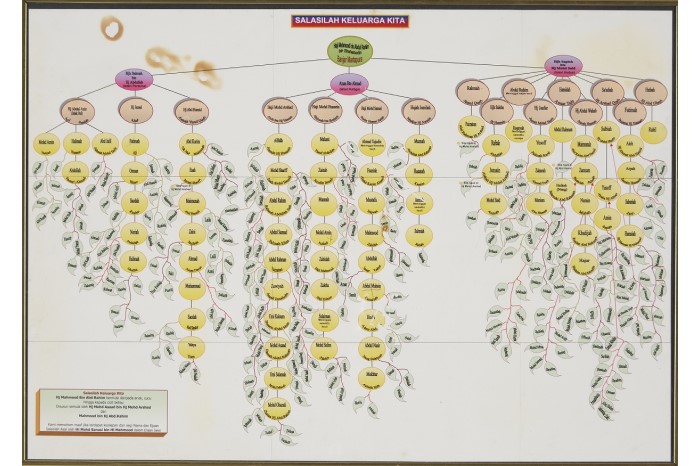

The family holds a central position in the Banjar community because families are both the source and bearer of Banjar history, culture and traditions. Many of the families in the Singapore-Banjar community can trace their lineage to ancestors who have travelled out of the Banjar Regency in South Kalimantan. Some arrived here in the late 19th century and maintained social and business links back in South Kalimantan through seasonal travel, trade and other commercial activities.

Marriages were also arranged between families in Banjarmasin and Martapura and migrant Banjar communities in various parts of the Malay Archipelago. Over time, being the smallest Malay sub-ethnic group in Singapore has meant having to marry outside their ethnno-cultural group and this phenomenon seems to have made the Banjar here more aware of the need to preserve elements of their intangible cultural heritage, including wedding customs and cuisine lest they disappear in the melting pot of multi-culturalism.

This section presents how some families have been expressing their Banjar cultural identity through practising various aspects of Banjarese culture in their daily lives.

2020Singapore

Collection of Malay Heritage Centre, National Heritage Board

2020

Singapore

Collection of Malay Heritage Centre, National Heritage Board

Many local Banjar families today are likely to eat food which is considered ‘Malay’ cuisine to the average person. However, many of the Banjar interviewed mentioned dishes which are specific to provinces and locales in South Kalimantan and were brought over to Singapore when their families relocated here.

While families with first-generation Singapore-Banjarese relatives grew up with Banjar dishes as everyday meals, successive generations are likely to enjoy them only during special occasions such as festive holidays, weddings andfamily and/or community gatherings. Nonetheless, these dishes are a simple yet meaningful way by which generations of Banjar families connect with one another and celebrate their culture.

Watch: Video of a traditional Banjar wedding reception in Banjarmasin

2019Indonesia

Source: SelingTV

Traditionally, Banjar families preferred to strengthen familial, economic and community ties through marriages amongst extended family members. Hence, it was not uncommon for urang Banjar who settled in Singapore and other parts of the archipelago, especially those from wealthier backgrounds, to matchmake their sons and daugthers of marriageable age with suitable cousins or even relatives of their in-laws.

A typical Banjar wedding would be a sizeable affair as entire families of relatives, both immediate and distant, are invited to celebrate the occasion. It is also not uncommon for Singapore-Banjar who still have familial ties in Banjarmasin, Martapura or Pontianak, to travel to ancestral towns or villages to attend wedding receptions.

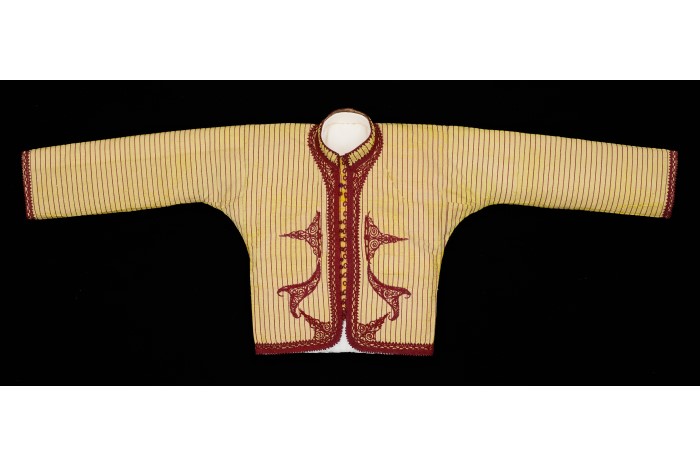

Becoming Banjar

The Banjar community in Singapore today continue to find means of commemorating their unique identity and heritage, including culinary heritage and their material culture! This includes dressing up in traditional finery on special occasions, including weddings, ceremonies and performances that involve other community members.

Do you also enjoy dressing up? Click here (for Facebook) and here (for Instagram) to see what you might look like with a traditional Banjartanjak worn by Banjar men, or here (for Facebook) and here (for Instagram) to see what you might look like with a Banjar-Malay bridal headdress from the 1950s – much like the examples you see below!

Try this filter!

Try this filter!

Conclusion

For many of the Singapore-Banjar community, the concept of ‘Banjar-ness’ is one that they do not take for granted due to the community’s small numbers as well as the gradual erosion of various Banjarese cultural practices and the decline in the use of basa Banjar amongst younger Banjar Singaporeans who relate more to a more homogenised Singapore-Malay identity.

Fortunately, the Banjar identity is kept alive here by second and third-generation Banjar who preserve and promote their traditions, language and culture through community initiatives such as language classes and cultural showcases, and by practicising customs such as cooking Banjarese heritage dishes and donning traditional wear during festive occasions and aruh ganal.

The concept of ‘Banjar-ness’ is further strengthened by familial ties and the sense of kinship which binds the local Banjar community to larger Banjar communities in South Kalimantan and other parts of the Malay Archipelago. This extended family also plays a key role in awakening, shaping and reiterating ‘Banjar-ness’ through the sharing of stories of historical events and how their forebears overcame challenges and made their mark in the societies where they settled.

As a result, the Banjarese adage ‘haram menyarah waja sampai kaputing’ continues to resonate strongly with the Singapore-Banjar community as being Banjar means having the determination to face challenges and succeed against all odds. Consequently, in spite of its small numbers, the local Banjar community has contributed in various ways to Singapore’s development as a young nation and continues to be an integral part of Singapore-Malay society.

Watch: Video recording of what “being Banjar” means to the Singapore-Banjar community

2020Collection of Malay Heritage Centre, National Heritage Board

A Banjar Odyssey

Step into the shoes of a Banjar merchant or diamond miner in the 1800s in this interactive text-based adventure game created by students from the Singapore University of Technology and Design. As you make decisions that dictate your life and fortune, learn more about the historical circumstances that shaped the Banjar community in the region.

Click here to start playing!