This baffled her. She looked Chinese, had Chinese ancestry but did not have a Chinese name.That simple act fuelled an interest in her origins.

Rosalind is Peranakan Chinese. “I come from an ethnic culture that not many people know about. Most people take it that you're half Malay and half Chinese, period. That's the most that they know,” she says.

She would learn that her ancestors, who were from China, arrived in the Straits of Malacca in the 19th century and married local women.

Religion was not on the forefront of these women's minds. They were more concerned about basic needs such as food, shelter and clothing — so they took on the religion of their husbands. As a result, Peranakan Chinese are not Muslims, and pork is a regular feature in their cuisine.

Her roots were very much alive at home. Rosalind 's mother came from Malacca, had Hokkien roots but spoke only Baba Malay, while her father was ethnically Chinese. His first wife only bore him two daughters after twelve years of marriage. Because sons were valued in Peranakan culture, he decided to take on a second wife.

“'My father was an Anglophile - the “King’s Chinese” as they were referred to then. His children would take the names of English kings and queens. My mother bore him eight sons and six daughters.” adds Rosalind. “Going by her lineage, I am fifth-generation Peranakan. My children are sixth and my grandchildren are seventh.”

Starting early

She later fundraised for the National Council of Social Service and was awarded the Special Volunteer Award. She has also been an air stewardess, worked in hotel management and real estate.

Rosalind retired at age 55. At that point, volunteering seemed like a natural next step. The Peranakan Museum had opened that year, just as she was entertaining the idea of becoming a docent.

A visit to the museum sealed the deal. On display was an artefact: a Catholic altar with carvings of the phoenix and qilins.

“I nearly fainted. I saw an artefact that once belonged to my family. I recognised it because I had seen it from afar, from the main door (of the home of my father's first wife),” she recalls. “I couldn't believe it so I brought some family members there. And, they said yes, it's the one.”

Looking back, she reflects, “I believed that I could add value to the museum. Plus, I was looking to contribute to society in the space of arts and culture, and better still, in the promotion of an ethnic culture which even my own ethnic group don’t know much about.”

Rosalind started training to be a docent in 2009. A year later, she was appointed co-head, and her responsibilities included training new docents.

Reaching out

Although there were requests for Mandarin tours at that time, she didn't speak the language, and wanted to present them with alternatives.

The tours were a hit. The museum would host a group of eight to ten seniors once every two months. As time went on, the tours were held twice a month.

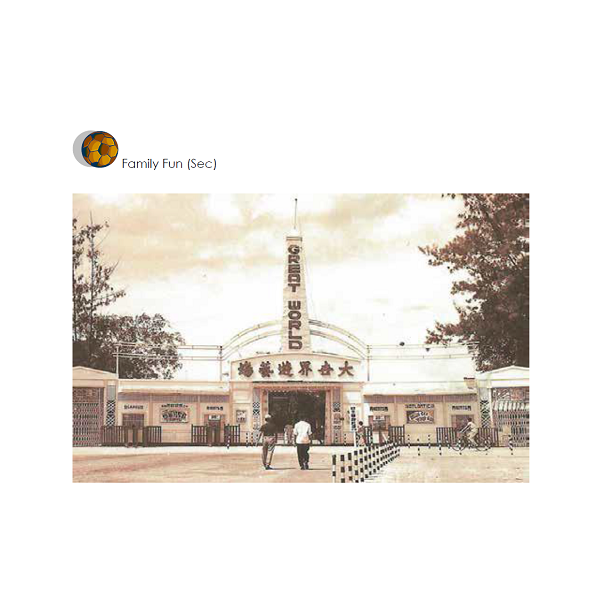

Elderly visitors loved the mock-up of an old kitchen, which was on display at the museum, and often shared their own stories of earlier times. Those who lived on Pulau Ubin would share that they reared chicken and ducks for a living. To get running water, they needed to pay 50 cents for the installation of water pipes, said Rosalind.

Then, the Alzheimer's Disease Association (ADA) wanted to take persons with dementia to the museum, as part of their therapy. Collaborating with The Peranakan Museum, ADA conducted a typographical survey in 2011, to ensure that it would be a safe environment. The route needed to be wheelchair-friendly and bright.

Rosalind also visited the association's New Horizon Centres with other docents. They found out more about its programmes for persons with dementia, which included arts and craft. They then decided that their museum tours for ADA’s clients would include the porcelain and kebaya galleries, to draw connections to familiar colours and patterns. Elderly visitors were also served tea with red dates before tours, to put them at ease.

“We are not trained medical personnel, so we needed to be very sensitive to how they would react to a new place. I think being friendly, warm and approachable is very important,” Rosalind says.

New horizons

ADA tours have since expanded to the National Museum of Singapore, with the launching of “Memories Cafe” in 2018. Held on Saturdays for persons with dementia and their caregivers, they visit two galleries which touch on Singapore in the 1950s, after a meal at the “Food for Thought” cafe.

The 65-year-old especially enjoys giving private tours. She feels there is far too much to tell in a typical hour. “I'd like to think that I have added some value especially in disseminating information about this niche culture.”

“To me, it is a great honour and privilege, and because of that, it's a tremendous duty. I must ensure I do the right thing, provide the right information and teach the children right, because oral traditions are not in the history books,” sums up Rosalind.

By Annabelle Liang