TL;DR

Two shipwrecks discovered in Singapore waters have yielded a precious hoard of artefacts that provide new evidence of the island’s place in ancient maritime networks.

MUSESG Volume 16 Issue 2 - July 2023

Written by Young Wei Ping, Independent Researcher

Co-authored by Conan Cheong, Curator, Asian Civilisations Museum

Read the full MUSESG Vol. 16, Issue 2 - July 2023

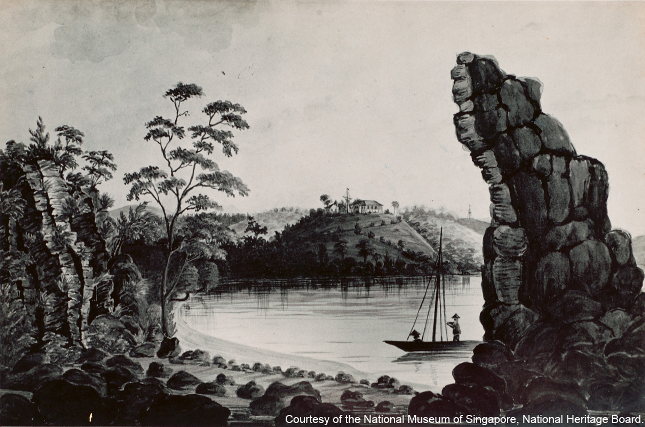

Among the displays in Singapore’s museums lie artefacts that speak quietly of the depth of the nation’s archaeological heritage. These objects tell the story of Singapore’s early history, which goes as far back as the 13th century when it was a port engaged in regional and international trade. While Fort Canning and other terrestrial, or land, sites frequently feature in discussions of Singapore’s archaeological heritage, there has been little representation of its maritime archaeological discoveries.

The seas around Southeast Asia have in fact been the site of several historically significant shipwreck discoveries since the 1970s. These date from as recent as the Second World War to the precolonial period, such as the Tang Shipwreck that sank in the 9th century—and was found in 1998 in the waters off Belitung Island in the Java Sea, some 600 kilometres southeast of Singapore. A selection of artefacts from the Tang Shipwreck Collection are currently on display at the Asian Civilisations Museum (ACM).

Closer to home, the waters around the island have in recent years yielded precious maritime archaeological material. Two outstanding historical shipwrecks discovered within Singapore’s waters are the mid-14th-century Temasek Wreck1 in 2015, followed by the 1796 Shah Muncher in 2019.

Underwater surveys and excavations of these shipwrecks conducted between 2016 and 2021 yielded approximately 10 tonnes of artefacts: four tonnes from the Temasek Wreck, and six tonnes from the Shah Muncher. The excavated materials range from Yuan-dynasty (1279–1368) porcelain and numerous ceramic cups, bowls and jars, to metal betel nut cutters and accessories.

One of the most extraordinary discoveries was the variety and quantity of Yuan blue-and-white porcelain found in the Temasek Wreck. Eminent archaeologist John Miksic wrote about the rarity of this find among shipwrecks in his 2013 publication:2

Blue and white porcelain was first produced in large quantities in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi Province, in the early fourteenth century. It was considered vulgar at that time, and only became popular among the Chinese elite in the early fifteenth century.

No shipments of blue and white ware have yet been discovered on Yuan shipwrecks. This presents something of a mystery but suggests that not much blue and white ware was being produced.

The findings from these shipwrecks have upturned long-held notions and yielded new perspectives of Singapore’s material culture. Similar artefacts, including Longquan greenware dishes, have been found in both the Temasek Wreck and in terrestrial archaeological sites such as Fort Canning and Empress Place along the Singapore River, with material dating to the 14th century. A comparative study of these discoveries from both land and sea contributes to a deeper understanding of Singapore’s maritime connections in the precolonial period.

Supported by the National Heritage Board (NHB), ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute and ACM, work has been going on behind the scenes to clean, document and study the artefacts in detail. Volunteers led by principal investigator Dr Michael Flecker have slowly chipped away at the large assemblage of artefacts to understand the two shipwrecks and their place in Singapore’s history.

Processing Artefacts

After being submerged for centuries, the artefacts retrieved from the two shipwrecks have naturally seen better days. Eroded, coral-encrusted and broken into pieces, the ocean’s elements had not been kind to the remains of the shipwreck. The salvaged artefacts had to undergo intensive conservation treatments in order to neutralise the damage they suffered.

First, the artefacts were treated to stabilise them outside the saline marine environment they were submerged in for centuries, before being washed lightly to clean off any surface residue. The latter was especially rewarding for the team as the process revealed the delicate decorative motifs and glazes of the artefacts—the sense of discovery was thrilling.

After this, a dedicated team of volunteers sorted and documented the artefacts into different categories. For the Temasek Wreck, in particular, this detailed sorting process went beyond the broad typologies of greenware, whiteware, stoneware and blue-and-white to determine the variety of the artefacts. Ceramics were carefully examined and then sorted based on their specific glazes, the quality of the clay, their shape and design, and the kilns they might be associated with.

Besides the unprecedentedly large presence of Yuan-dynasty blue-and-white porcelain, there were also numerous Longquan greenwares, white Qingbai bowls and dishes, small-mouth jars and coarse stoneware, among other finds.

Under the team’s scrutiny, specific artefacts of interest were observed among the fragmentary remains. These include clues hinting at the interconnections of Southeast Asia’s maritime activity as well as a variety of ornate decorative motifs: a friendly-looking dragon moulded in the centre of a dish, a ceramic sherd with a Chinese stamp and another with an Arabic stamp featuring decorative flowers on the rim. Some vessels also had abstract waves and motifs carved onto the ceramic surface, among many other finds. These pieces provide a mere glimpse into the rich variety of the ship’s cargo.

The team collects basic data such as the quantity and weight of the artefacts before photographing and packing them for longer-term storage. This data, along with visual documentation and detailed observations of the artefacts, are then consolidated into databases, providing an overview of the shipwreck assemblage for researchers and museum practitioners. This documentation work is ongoing.

Maritime Archaeology as a Platform for Engagement

There has been much discussion of Singapore’s role in historical Southeast Asian maritime networks. However, as this study is often centred on textual historical sources, the wealth of insights that could be drawn from maritime archaeological material remains mostly untapped.

Increasingly, though, maritime archaeological findings have found their way into museums, such as the Tang Shipwreck display at ACM. More recently, selected highlights from the Temasek Wreck and the Shah Muncher have been put on display in ACM’s Singapore Archaeology Gallery.

One of the focus areas of NHB’s Our SG Heritage Plan 2.0 is the conservation of Singapore’s maritime heritage. As part of this plan, there will be greater funding and support for the research and safeguarding of maritime archaeological material. The latter often requires unique interventions to stabilise and store the artefacts following their extraction from marine environments.

Needless to say, maritime archaeology is a massive undertaking, an effort only made possible with help rendered by passionate volunteers. In both the Temasek Wreck and the Shah Muncher shipwreck excavations, volunteers helped catalogue the excavated artefacts, contributing significantly to the recording of Singapore’s maritime heritage and material culture. These volunteers, who are members of the Southeast Asian Ceramic Society and Friends of the Museum, all share a common interest in documenting Singapore’s cultural heritage.

Most people would only ever encounter these artefacts from a distance, through the barrier of a display case in a museum gallery. Being able to directly handle artefacts, many of them centuries-old, is a rare privilege. Holding these archaeological ceramics in one’s hands allows for more intimate observations: the indentation of fingerprints from potters centuries ago, the asymmetry of mistakes introduced when crafting each piece, and the imperfectly executed stamps on the surface of a ceramic piece. Through these ‘flaws’, we glean traces of the human touch that have led to the creation of these wares—bridging a connection to those in the past, if you will.

Maritime Artefacts at the Asian Civilisations Museum

As a first step towards making the precious discoveries from the Temasek Wreck and the Shah Muncher accessible to the public, ACM unveiled a selection of artefacts from these shipwrecks in its Singapore Archaeology Gallery in January 2022.

In conjunction with this new display, one of the showcases in the main Maritime Trade Gallery is dedicated to ceramics from the cargoes of six other shipwrecks. These are the Hatcher Cargo, and wrecks of the Vung Tau, the Götheborg, the Geldermalsen, the Diana and the Tek Sing. The Diana was, like the Shah Muncher, a country ship that was wrecked in 1817. Both the Diana and the Geldermalsen carried blue-and-white porcelain of a very similar design to those found in the Shah Muncher, reflecting European tastes in tableware at the time.

The final shipwreck in ACM’s collection, the 9th-century Tang Shipwreck, resides in a permanent space, the Khoo Teck Puat Gallery. Originally bound for Iran and Iraq, the Arab dhow met its unfortunate end near the island of Belitung, off the coast of Sumatra in Indonesia. It had been loaded with precious cargo from China, such as gold and silver as well as ceramics from the Xing, Ding, Yue, Changsha and Guangdong kilns.

The layout of ACM’s galleries has been designed such that visitors can see how the Temasek Wreck and the Shah Muncher fit into the larger story of maritime trade and international commerce in Asia. The Maritime Trade galleries on the first floor, which include the Singapore Archaeology Gallery and the Tang Shipwreck Gallery, reveal the history of Asian port cities and globalisation through displays of Asian export art.

Highlights from the Temasek Wreck

The most outstanding artefact in the Temasek Wreck display is likely the only intact blue-and-white vessel that was salvaged. The shape of this vessel is unique among Yuan blue-and-white porcelains. The flange around a tall neck suggests it might have been used as a hookah (water pipe) base. The darker spots of inky blueblack cobalt pigment in certain areas of the decoration, known as the ‘heaped and piled’ style, date it to the 14th century.

When the vessel was first uncovered by ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute archaeologist Michael Ng, it looked like a discarded object—such was its state, its delicate design obscured by encrustations of sediment and coral. A small screen next to the vessel in the gallery plays a video capturing the moment of discovery and its subsequent careful retrieval from the ocean bed. Blue-and-white porcelain, like this one, made in the Jingdezhen kilns in Jiangxi Province, may be considered as the first global ‘brand’ of luxury goods that were exported from its production base. These wares were in high demand across Asia and the Middle East—and, it seems, in Singapore as well.

Also on display in the gallery are exquisite fragments excavated from the shipwreck site. These span a large variety of ceramic forms: bowls, stem cups, jars and other types of vessels. It is believed that the port of call of the sunken ship was Temasek (as Singapore was known then). One piece of evidence that points to this is the iconography of a mandarin duck in a lotus pond— the signature motif of Yuan dynasty’s Wenzong Emperor (r. 1328–32)—in blue-and-white porcelains excavated from both the Temasek Wreck and from Temasek-period land sites in Singapore.

Besides blue-and-white porcelain, the Temasek Wreck also yielded large quantities of Longquan ceramics, many of them intact. Famed for their thick, wax-like green glazes ranging from seafoam and jade-green hues to shades of olive, Longquan ceramics were exported in large quantities all over Southeast Asia, Japan, Korea and the Islamic world from the 10th to mid-15th centuries. One fine example on display is a barbed-rim dish incised with a rare design of twin phoenixes in the centre.

Another noteworthy artefact in the gallery is an inkstone, one of the few non-ceramic items recovered from the Temasek Wreck. Inkstones were used for grinding solid inksticks with water to make liquid ink. The lack of ornamentation and the rough chisel marks on the underside suggest that this inkstone served a purely utilitarian purpose.

Highlights from the Shah Muncher Wreck

The second shipwreck, the Shah Muncher, was identified as a country ship—a category of merchant vessels built in India to ply the China–India trade, operating under licence from the East India Company. This deduction was based on parts of the Shah Muncher’s hull structure as well as the surviving ship’s gear, such as its rigging, anchors and iron cannons.

The Shah Muncher traded Indian cotton for sugar, zinc and porcelain from China. It was built in 1789 for Sorabjee Muncherjee (1755–1805), a prominent Parsi merchant in the Bombay export trade. Although the vessel sank in 1796— some 23 years before Raffles established a British trading post in Singapore—its cargo gives us an idea of the kind of goods that might have been purchased and subsequently transshipped in the region.

Aside from a large ceramic cargo, archaeologists found tutenague (zinc ingots), glass case bottles (designed for easy packing into wooden cases or crates), glass wine bottles, copper alloy bracelets as well as thousands of agate medallions and glass beads. The gallery exhibits a representative selection of this broad range of cargo.

The Shah Muncher also yielded other fascinating objects that provide insights into some of the people who were on board the ship—for instance, Armenian merchants. Their presence on the final voyage of the Shah Muncher is suggested by the personal effects found, such as three mother-of-pearl seals and a small gold tag, all inscribed with Armenian script. Armenian merchants, who had established extensive trading networks in Asia and Europe since the 17th century, both competed and cooperated with British East India Company agents in the pursuit of profit.

To enhance the visitor experience, the gallery features an immersive video depicting the experience of maritime archaeologists in the course of their work. Viewers get a chance to see them dive among fish, coral and churning sand to salvage precious artefacts in the challenging yet beautifully surreal environment.

The video is accompanied by a soundscape composed of recordings made during the excavation. Titled ‘Senescence’, which means biological ageing, the aural work interprets a shipwreck as one large, dying organism—suggesting that even as the ship loses its function as a vessel to move humans across the seas, it becomes a harbour for new life.

The artefactual representation of the historical individual via archaeological assemblages humanises the past. Maritime archaeological sites are akin to time capsules: beyond the excavated cargo, the ship’s crew are also represented by their possessions at the time of wrecking.

The imaginative appeal of maritime archaeology can in a sense embody larger-than-life historical narratives, making it an invaluable resource for heritage outreach and education. With the spotlight increasingly trained on Singapore’s rich maritime heritage, the public can expect to see more of its sunken treasures being showcased, even as the story of Singapore’s early history continues to unfold with ongoing archaeological projects in the waters around Singapore and Southeast Asia.

A large green-glazed ceramic platemade in the Longquan kiln in Zhejiang Province, China, excavated from the 2015 archaeological dig in Empress Place, where the Asian Civilisations Museum is currently located.

Currently on display in the Singapore Archaeology Gallery,this large green-glazed ceramic plate was made in the Longquan kiln in Zhejiang Province. It was one of the significant archaeological finds from the Singapore Riversite at Empress Place, near the Asian Civilisations Museum. Teams from the National University of Singapore and ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute had carried out excavations on thebanks of the Singapore River in 1998 and 2015 respectively.

Featured alongside other finds from the 2015 excavation,the plate is strategically sited right in front of a windowoverlooking the original riverside excavation site, whichis now lined with a row of shady rain trees. Artefacts fromthe Temasek Wreck are placed next to those from Empress Place and Fort Canning to encourage visitors to see the connections between Temasek-era archaeological sites that span land and sea.

Excavations along the Singapore River, including EmpressPlace, yielded various Chinese ceramics—celadons, blue-and-white wares and white vessels from Dehua—amongstother finds. These would have been traded for products suchas wood and cotton from the Malay Peninsula and the Riau Islands. The abundance of these goods is evidence of thelively commercial centre that was 14th-century Temasek.

All images courtesy of Asian Civilisations Museum.

The authors would like to thank Dr Michael Flecker, Visiting Senior Fellow with ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, for his help in reviewing this article.

Notes

- It has been referred to as the Temasek Wreck due to the likelihood that the ship’s journey included 14th-century Temasek (present-day Singapore).

- John N. Miksic, Singapore & the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300–1800 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2013), 293.