One of the military units that defended Singapore from the Japanese was a group of Chinese volunteers with barely any training or weapons.

Cheng Seang Ho was not a typical soldier. She was a 66 year-old grandmother. However, on 11 February 1942, she fought fiercely in the Battle of Bukit Timah, firing a shotgun at the Japanese invaders, taking shelter with her husband behind a row of blasted tree stumps.

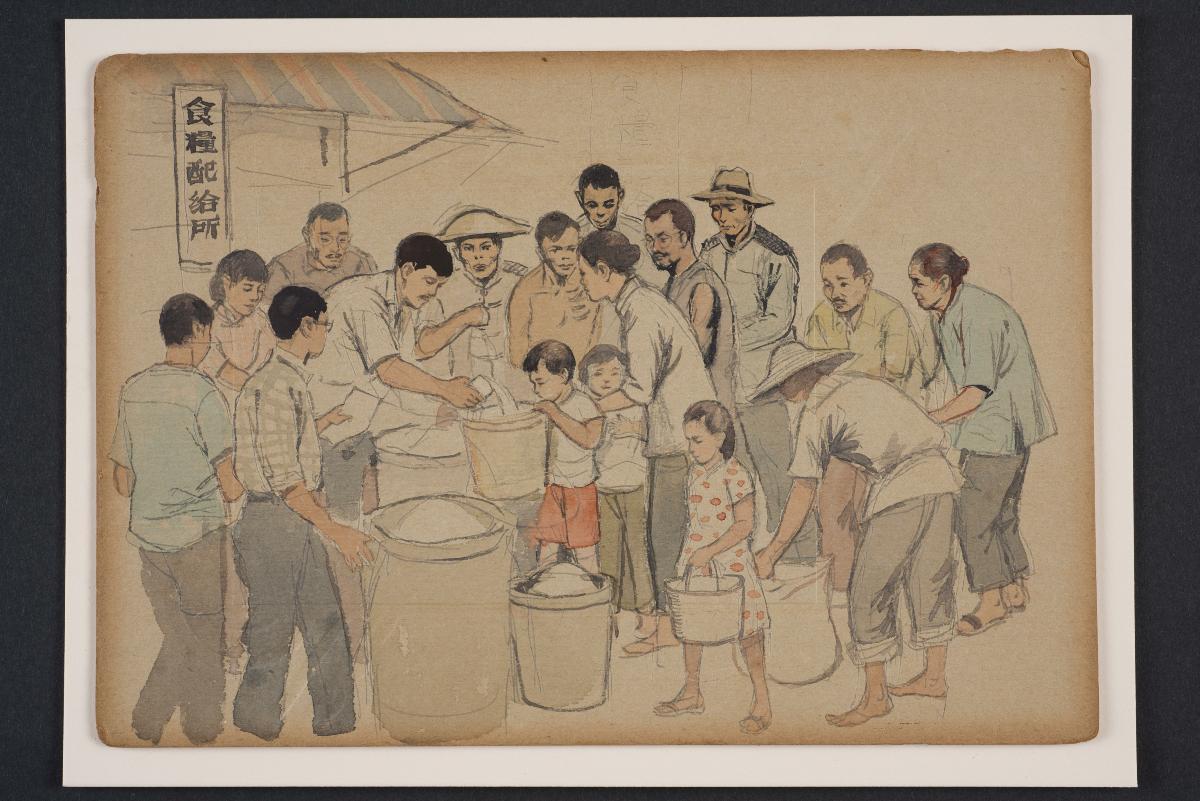

She was part of a small army called Dalforce. Her fellow soldiers came from all walks of life. They included students, labourers, office workers, secret society members, rickshaw pullers, and dancing girls from nightclubs. Many were members of the Malayan Communist Party. They had been released from prison, just so that they could fight to defend Singapore.

The British had recruited their army only a month earlier, in January. Before that, they had not trusted the Chinese enough to defend Singapore. Instead, they had decided to mainly use soldiers from other parts of the British empire, such as Australia and India.

However, as soon as they made a call for Chinese volunteers, thousands of people turned up. Not all of them were from Singapore. Some from Malaya crossed the Causeway just so they could help with the war effort. Around 3,000 people were recruited, although only about 1,250 were actually enlisted into training.

The Chinese called this army “the Singapore Overseas Chinese Volunteer Army” (星华义勇军). The British called it Dalforce, using the name of the commander, John Dalley, a lieutenant colonel from the police. He had been trying to convince the government to form this army from way back in 1940.

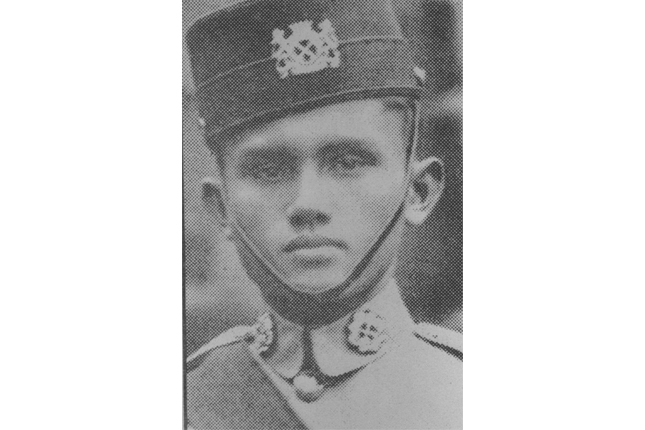

Now, there was no time to prepare these new soldiers properly. They were only given three to 14 days of training in basic military skills. On 5 February, they were sent into action, wearing blue uniforms, with red triangles on their right sleeves.

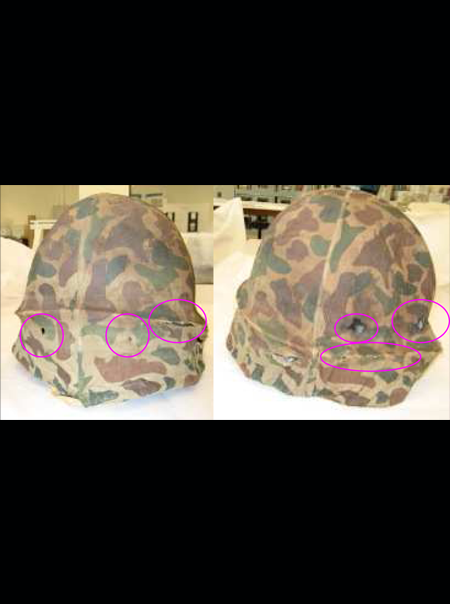

The soldiers were extremely poorly equipped. They had no helmets, so they wrapped yellow cloths around their heads. They also had very few weapons: long knives called parangs, shotguns and hunting rifles, some with as few as seven bullets. They were not even given enough food supplies.

Nevertheless, they impressed the full-time soldiers from Australia and the United Kingdom with their toughness and bravery. In Kranji, one unit battled against a Japanese machine-gun battalion until all 200 of them were killed. In contrast, an Australian unit retreated from the location, even though it was armed with machine guns.

There are unconfirmed stories that they managed to sink several rubber rafts which the Japanese used to travel from Malaya. General Yamashita actually considered stopping the invasion on 10 February, because the resistance was so strong.

Dalforce member Teo Choon Hong later explained to researchers why he had fought so desperately. “I didn’t think I would be safe behind the line,” he said. “Since it wasn’t safe, I might as well go to the front to resist them, to fight them. If I could kill one Japanese my sacrifice would be rewarded.”

Sadly, these heroes could not change the course of the war. On 13 February, Lieutenant Colonel Dalley gathered them at headquarters and announced that the British government had decided to stop fighting. He paid each of the volunteers $10 and made them give up their weapons. He then ordered the weapons to be buried.

300 Dalforce soldiers were killed in the battles. Many more would be slaughtered by the Japanese during the Occupation, including Madam Cheng’s husband. Some of them continued to fight secretly in the jungles as part of the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army.

Madam Cheng herself survived the war. In 1957, she attended the opening ceremony of the Kranji War Memorial. She refused to wait for the British Governor to lay down his flowers, and walked in front of him instead, so she could mourn her husband and her fellow soldiers.

Notes