TL;DR

The way we dress can reflect how we see ourselves and influence how others perceive us. If so, how has the sarong kebaya evolved and what does it reveal about the place of Peranakan women in Singapore today?

MUSESG Volume 16 Issue 2 - July 2023

Written by Selina Chong, Assistant Director, National Collection, National Heritage Board

Read the full MUSESG Vol. 16, Issue 2 - July 2023

Image above: A sarong kebaya-clad Ivan Heng playing the titular character in Emily of Emerald Hill, 2019. Courtesy of Wild Rice.

The sarong kebaya is possibly one of the most visible expressions of Peranakan culture, both in Singapore as well as across the region. But the sarong kebaya that communities in Southeast Asia are familiar with is not unique to Peranakan culture. I have used Peranakan culture as the frame of reference in this article as it is the cultural heritage that I am most familiar with (interested readers may wish to explore other sources for insights into the sarong kebaya in the wider Nusantara region1).

Coined in the late 18th century, the word ‘sarong’, meaning ‘to wrap’, refers to a long tubular cloth tied around the waist.2 Kebaya is said to be derived from qaba, a jacket said to be of Turkic origins and worn at least since the 9th century by the ruling elite across the Middle East, Central Asia and North India. Another hint of the kebaya’s Middle Eastern origins is found on the garment itself: a triangular patch under each arm of the kebaya—a feature also seen in traditional robes of the Middle East. Ming-style jackets, on the other hand, are flat-cut (without the gusset).

Today, different forms of the sarong kebaya continue to be made and worn by women across Southeast Asia. The garment is so well loved that Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand have come together to jointly submit a nomination to inscribe the kebaya on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in March 2023.

As thinkers and writers have previously articulated, clothes do much more than protect our bodies from the physical elements. French philosopher and feminist activist Simone de Beauvoir describes the dynamics between attire and gender in society in her influential book, The Second Sex:3

A man’s clothes, like his body, should indicate his transcendence and not attract attention; for him neither elegance nor good looks calls for his setting himself up as object; moreover, he does not normally consider his appearance as a reflection of his ego.

Woman, on the contrary, is even required by society to make herself an erotic object. The purpose of the fashion to which she is enslaved is not to reveal her as an independent individual, but rather to cut her off from her transcendence in order to offer her as prey to male desires: thus society is not seeking to further her projects but to thwart them.

Inspired by de Beauvoir and other feminists, this article explores what the sarong kebaya reveals or reflects about a woman’s place in society.

Form and Function

Many researchers regard the baju panjang (literally ‘long dress’) as the precursor to the more familiar sarong kebaya that we recognise today. The baju panjang is typically a loose-fitting, calf-length tunic with sleeves that taper at the wrists. When paired with an ankle-length wrap or skirt (sarong), the baju panjang is fastened at the front with buttons or a brooch.

It was not just local women in the region who wore the baju panjang or kebaya. By the mid-19th century, European and Eurasian women in the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia) also began wearing kebaya made of white lace, pairing them with expensive cotton batik sarongs—a sartorial combination that hinted at status and privilege. Some of these kebaya featured lace inserts that provided comfort in the tropical climate of Southeast Asia.

Before the mid-19th century, the kebaya was relatively loose-fitting, particularly the versions worn at home or at informal occasions. From the 1850s onwards, however, a version of the sarong kebaya evolved into a tighter, more form-fitting garment.4 This development mirrored the decline of modest Victorian fashion for women in England as well as the gradual tightening of the silhouette as seen in the cheongsam, the body-hugging one-piece dress that was just taking off in China’s fashionable cities.

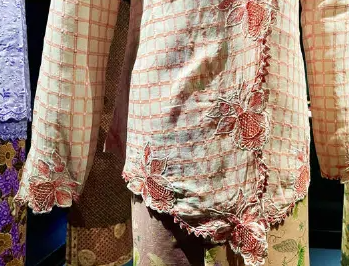

Unlike the baju panjang, the kebaya was shorter—ending at the hips—and gently nipped in the waist. These minor adjustments had a flattering effect on the wearer’s figure, highlighting her curves. The kebaya was also decorated with lace (kebaya renda) or embroidery (kebaya sulam), with the latter gaining greater prominence and popularity in tandem with the rising affluence and influence of the Straits-born Chinese Peranakan community. This led to the emergence of what we know now as the modern kebaya.

On the other side of the world, the accidental discovery of aniline dyes in 1856—the first commercial products of the synthetic chemical industry— revolutionised the manufacture of clothing. Prior to the introduction of chemical dyes, colour in clothing used to carry specific significance.

Yellow, for instance, was reserved for royalty during the Qing dynasty (1636– 1912) in China, while saffron-dyed robes continue to define monastic orders in both Theravada Buddhist and Hindu traditions today. In Europe, richly coloured garments were worn by aristocrats and the middle class, in contrast to the working class who donned simple garments in dark monotone shades as an implicit form of protest against bourgeoisie excess.

With synthetic dyes, however, any hue imaginable was now possible with the careful calibration of chemicals. The affordability of aniline dyes also meant that anyone could now introduce colour to their wardrobes, tearing down barriers that once rendered some shades the preserve of certain classes.5

The proliferation of synthetic dyes was accompanied by another watershed development in the garment industry: the birth of ready-to-wear clothing in the 1850s. This was made possible by the invention of the sewing machine in the late 18th century, which in turn allowed for the mechanisation of garment-making.

However, the kebaya continued to be hand-sewn, in part because it was a traditional skill—alongside other aspects of domesticity such as cooking and cleaning—that were valued by Peranakan women. It was only after the Second World War, when the price of lace increased exponentially, that machine embroidery became more common. Similarly for kebaya sulam, elaborate embroidered patterns with cutwork could now be achieved in much less time. Kebaya designs thus flourished, limited only by the imagination and skill of their makers. From these developments emerged the form of the sarong kebaya as we know it today—in a diverse combination of colours and embroidered patterns.

The myriad options of the sarong kebaya enabled women to express their identities through what they wore. Within the Straits-born Chinese Peranakan community, the outfit of a nyonya6 took on great significance. While a baba had access to academic and career opportunities because men were held in high esteem in traditional Chinese society, a nyonya’s place in life was one of domestication and cultivated gentility. To a large extent, a nyonya was seen as a reflection of her family’s status: she was expected to be submissive and carry herself with appropriate decorum. How she dressed—from the design of her kebaya to how she accessorised with jewellery—was a public statement of her family’s wealth and social status.

The gold and diamond belt above, for example, would have been worn by a nyonya to complement her sarong kebaya. The belt was probably made by South Asian craftsmen for a wealthy nyonya around the beginning of the 20th century. It comprises 18 linked gold pierce-work panels, each bearing the image of a peacock surrounded with a profusion of vegetation. The buckle and smaller side panels feature diamonds of yellow, brown and even orange-pink tints. In the centre of the buckle is a large European-cut diamond set in the body of the peacock. The buckle, which weighs in at nearly five carats, can be detached and worn as a brooch. This is not only an ostentatious piece of jewellery featuring intricate craftsmanship, but was also worn to show off the wealth of the wearer and her family.

Gender as a Social Construct

One of the most quoted statements about gender—“One is not born, but rather becomes, woman"7 —is attributed to Simone de Beauvoir. Her statement speaks to how gender identity, as with any other identity one holds, can be expressed and constituted through language, gesture and dress, among other things.

An example is the literal performance of gender—when dress and costume are used by an actor to assume a different identity. In the novel Orlando, Virginia Woolf writes:8

Vain trifles as they seem, clothes have, they say, more important offices than merely to keep us warm. They change our view of the world and the world’s view of us… There is much to support the view that it is clothes that wear us and not we them; we may make them take the mould of arm or breast, but they mould our hearts, our brains, our tongues to their liking.

The construction of gender through sartorial means is central in wayang peranakan, which is traditionally performed by Chinese Peranakan men in Baba< Malay, a creole spoken by the community. This theatrical form was derived from a blend of Chinese wayang (opera) and bangsawan, a popular form of Malay theatre.

Female impersonation was a distinctive feature of wayang perakanan as it was considered improper at the time for Chinese Peranakan women to be seen on stage. Baba performers of wayang peranakan would dress in women’s attire such as the sarong kebaya and adopt coquettish poses and high-pitched voices. While contemporary stagings of Peranakan theatre today routinely feature actresses, it is not unusual to find men still taking on the odd female role or two.

Singaporean thespian Ivan Heng’s highly acclaimed performance in 1999 as the titular character in Emily of Emerald Hill was a nod to wayang peranakan. This was a role that Heng has reprised several times since, the last in 2019. Written in 1982 by Stella Kon, the monologue centres on a nyonya matriarch who devotes her life to her family, yet finds that she loses what she loves most in the end.

In 2019, to celebrate the opening of the Ngee Ann Kongsi Theatre @ WILD RICE, Raymond Wong, a veteran practitioner of Peranakan beadwork and embroidery, created beautiful sarong kebaya outfits for the restaging of the play. To symbolise Emily’s resilience through all the hardships she endures in her life, Wong stitched together a kebaya with embroidered chrysanthemums, a flower that blooms even in harsh weather. The outfit was key to Ivan Heng’s embodiment of the character of Emily Gan: wrapped in a vividly coloured sarong kebaya, the actor channelled the indomitable spirit of the matriarch to critical acclaim.

Contemporary Expressions of the Kebaya

The sarong kebaya has never ceased evolving; its shape and style continue to change with the passage of time, reflecting shifting societal norms. Needless to say, women in Singapore today have much greater autonomy than in the past. They enjoy privileges that were not afforded to their mothers and grandmothers, such as access to education and opportunities in the workplace. What this means is that many women have the financial means to buy what they want, decide what they want to do and are empowered to express their identities in myriad ways, including fashion. But while there is generally a growing appreciation among younger Singaporeans for their cultural heritage in terms of tradition, food and dress, in an era dominated by fast fashion, does the sarong kebaya still resonate with the modern Chinese Peranakan woman?

Personally, I believe so. The sarong kebaya remains a highly visible identity marker for me as a Chinese Peranakan woman. While not every person who dons the ‘nyonya style’ sarong kebaya will identify as Chinese Peranakan, it is still a source of joy and immense pride for me to witness how an ensemble of textiles can convey so much about identity, symbolism, artistic expression and exquisite craftsmanship.

Of course, I also look forward to the day that the sarong kebaya is perceived less as an occasion wear. I see sparks of that when I walk into Kebaya by Ratianah along Bussorah Street and hear owner and kebaya maker Ratianah Binte Mohd Tahir sharing passionately about her work. I celebrate when local and international designers play on the versatility of the kebaya and create inspired works that women can wear any day.9 I find every opportunity to support local makers because we—as a society—are at risk of losing the technical skills and expertise of our artisans and crafts(wo)men.

Notes

- A good place is the National Heritage Board’s Intangible Cultural Heritage inventory (https://www.roots.gov.sg/en/ich-landing/ich/Kebaya).

- Peter Lee, ‘Sarong and Kebaya: The Spectrum of Hybridity in Peranakan Fashion and Identity, 1600–1950’ in Singapore, Sarong Kebaya and Style: Peranakan Fashion in an Interconnected World (Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, 2016), 10.

- Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (New York: Vintage Books, 2010), 1098.

- Other forms of the garment, e.g.,kebaya labuh (long kebaya), also continued to be worn by women.

- It should be noted that chemical dye production has led to widespread water pollution. Some sources estimate that the fashion industry is responsible for up to 20 percent of industrial water pollution in producer countries such as Bangladesh, and wastewater—which can contain carcinogenic chemicals and heavy metals—is commonly discharged directly into rivers and streams, eventually flowing into seas and oceans, decimating ecosystems.

- Chinese Peranakan women are commonly referred to as nyonya, while the men are called baba.

- de Beauvoir, 2010, 555.

- Virgina Woolf, Orlando (London: Alma Books, 2014), 176.

- The Peranakan Museum showcases a few such examples.