Text by Iskander Mydin

Images by National Museum of Singapore Collection

BeMuse Volume 5 Issue 1 - Jan to Mar 2012

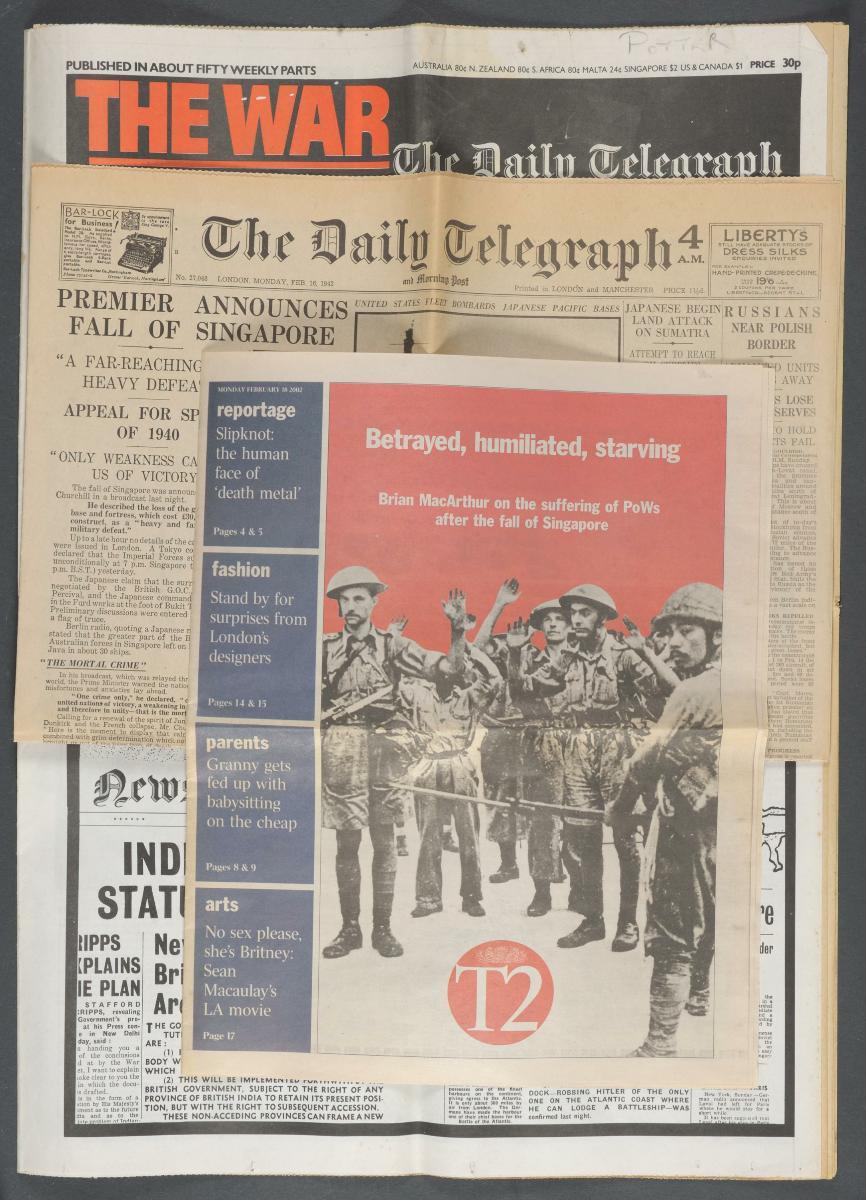

The passage of time opens a window for hindsight to enter, allowing us the privilege of retrospection. In this context, a pivotal event like the fall of Singapore to the Japanese army on 15 February 1942 and subsequent military occupation by the Japanese has invoked, over the years, a long and still unending river of memories, publications, documentaries, public exhibitions and other forms of remembrance, so much so that it could arguably be regarded as "the most remembered event" in the history of Singapore.

The long shadow of 1942

The conquest of Singapore was linked to a chain of Japanese attacks which began with dramatic speed from the last hours of 7 December 1941 into the dawn of 8 December 1941. Within this short period of time, the Japanese military struck across 6,000 mils of ocean westward from Hawaii to Wake to Guam to Hong Kong to the Philippines to Malaya and Siam1. The first months of 1942 marked the peak of the Japanese military conquest not only of Singapore, but also of the European colonial territories in the Pacific region.

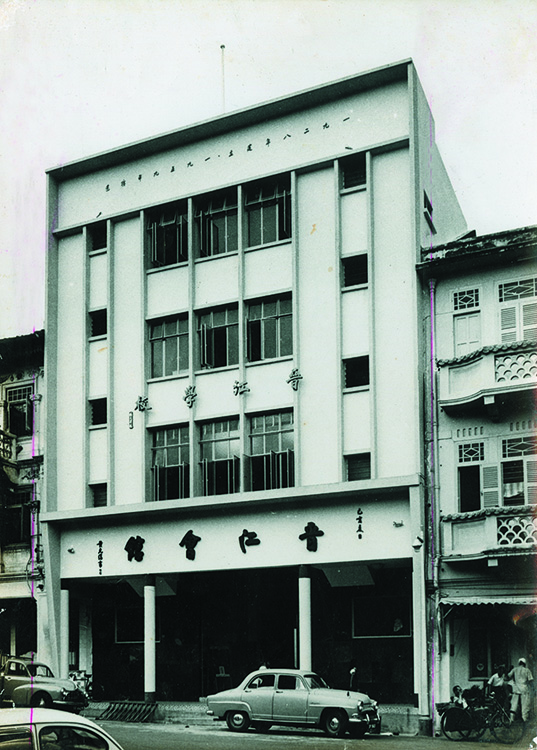

The conquest in 1942 marked the end of one formative phase of Singapore's history and the beginning of another. The earlier phase began in 1819 when the island was established as an entrepot by the British and Malay chiefs. It had developed into Southeast Asia's premier city by the time of the Japanese invasion. The Japanese victory overthrew more than 120 years of continuous colonial rule and abruptly ended this phase in Singapore's history.

1942 also marked the beginning of the phase in Singapore's history that could be considered as a generative process. The abrupt break from colonial rule in 1942, coupled with the experiences of defeat and occupation, contributed to a process of political awakening. This was reflected in the struggle for decolonization over the decade following the surrender of Japan in 1945.

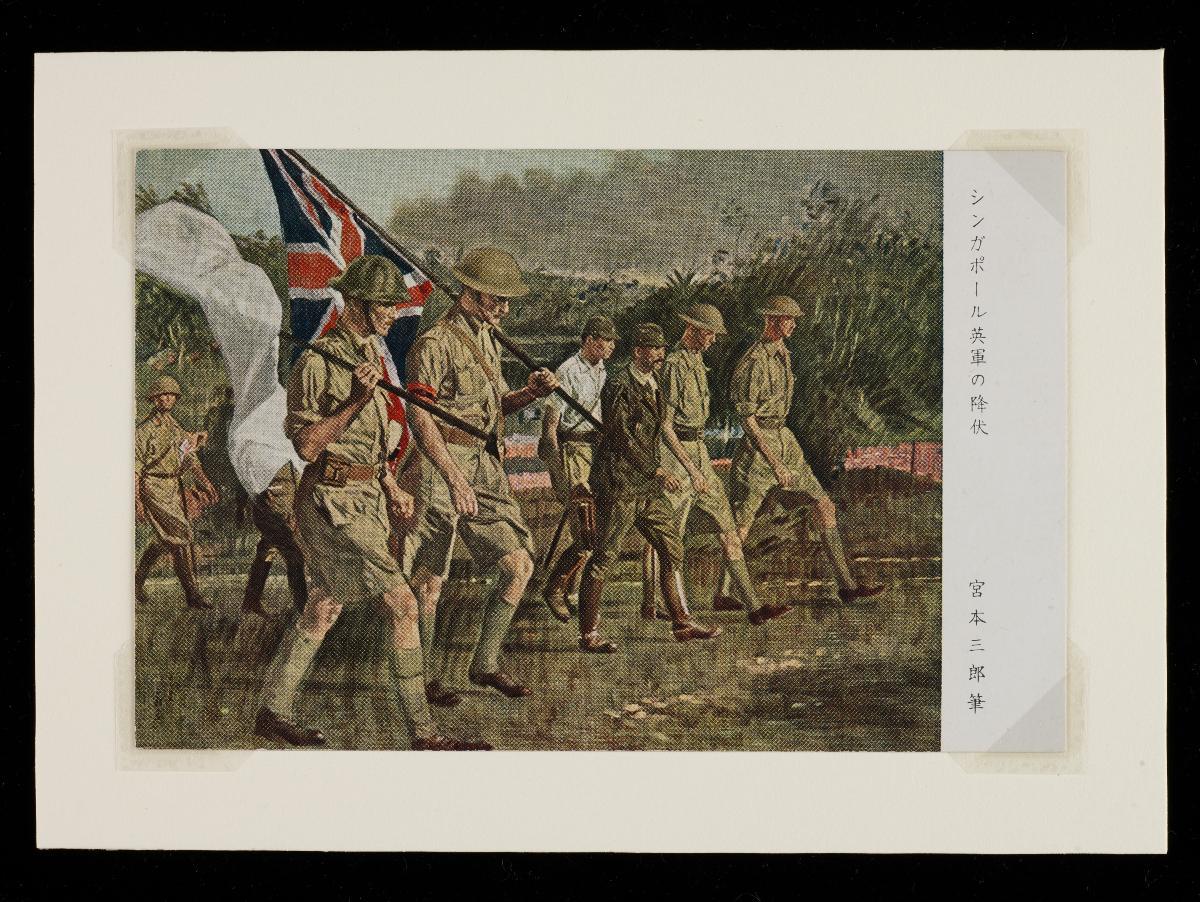

Japanese invasion and British surrender

The invasion started in early-December 1941 with the first Japanese aerial bombing of Singapore, and ended on 15 February 1942 with the British surrender. During this period of about two and a half months, the entire population of disparate migrant communities, as well as the colonial establishment, witnessed or experienced the full-scale horrors of modern war on the island. Among those were aerial and artillery bombardment, the sight of abandoned corpses of those killed in the fighting or bombing, the flight of refugees from the peninsular to the island, family separations in the midst of flight, as well as incidents of rape. With the impending British defeat, many foreigners and locals took flight in small vessels, desperately seeking the safety of Australia or British India, while last pockets of resistance against the invaders persisted amid the chaos and confusion of collapse.

The imminent danger following the surrender was looting2. A desolate sense of abandonment can still be felt in this account of the scene at the landmark Fullerton Building:

"... Doors, desks, cupboards, safes, and suitcases had been broken open, their content strewn everywhere over piles of empty tins and human ordure: it is a blessing that walls cannot speak or Fullerton Building would never cease from shame. Clothes, shoes, notebooks, diaries, letters, wills, bank books, insurance policies, photographs of loved ones, and all manner of personal articles...lay in utter confusion. Pictures of children were trampled into the crumpled pages of a Bible; socks were soaked in the juices of empty tins; a can opener ripped through shirts; trousers and coats were torn apart as if the looters had fought. Such was the demise of Raffles' settlement."

The Japanese Occupation

The British surrender was followed by three years and eight months of Japanese military occupation. The period began on an ominous note. Screening and collective punishment was imposed on the Chinese community, resulting in the massacre of thousands of Chinese males during the Sook Ching incident. Monetary contributions were also forced from the Chinese community as a “token of atonement”. Thousands of defeated Allied soldiers were imprisoned and many were sent to work on the Death Railway. Looters were executed and their heads put on public display. In the course of the occupation, food rationing was imposed and the black market came into operation as a result. Many Eurasians were re-settled under agricultural land schemes in Endau and Bahau to grow food. An Indian National Army was also formed out of defeated British Indian Army soldiers as well as local volunteers to fight for India’s independence from British rule.

Spies, informers and confessions under torture became a dreaded phenomenon during this period of time. As the experiences of invasion, defeat and occupation had significantly altered the fates of thousands of individuals, the oral history recordings of a generation of survivors deposited in the National Archives of Singapore still constitute an emotionally moving account of what it meant to undergo and experience the “lived time” of 1942 and after.

Landscape of Memories

1942 and its three subsequent years are remembered in contemporary Singapore through a variety of “landscapes of memories”. Among these are memorial sites such as the Kranji War Memorial, the Memorial to the Civilian Victims of the Japanese Occupation, as well as other locations where the war and occupation left its traces, including the Changi Murals and the Johore Battery site. There are also markers of the Japanese landing sites at Sarimbun and Kranji, and that of the Indian National Army Monument. Permanent displays such as the Memories at Old Ford Factory, Reflections at Bukit Chandu, Changi Museum, the Surrender Chambers at Sentosa and The Battle Box, together with guided battlefield tours and trails relating to 1942, are also additional aspects of this landscape.

Apart from these, there are other links in this landscape which bear the marks of “Fortress Singapore”, a term popularly used in the pre-World War II period to refer to the chain of coastal fortifications, airfields, garrison barracks and the naval base, constructed as a deterrence against enemy invasion. These former defences include the preserved coastal fortifications at Fort Siloso on Sentosa; the former Royal Air Force airfields at Tengah, Seletar and Sembawang; the remnant structure of the former Naval Base; the Admiralty House; Command House; the military barracks at Selarang and Gillman; as well as traces of the Base Ordnance Depot at Alexandra.

It can be seen that 1942 and after have left a deep imprint on the landscape. These sites and traces on the surface, underground (tunnels and former ammunition storage areas), and along the shoreline (former dock structures of the naval base) are indications that this relatively short period of time has – more than any other period in Singapore’s history – left behind what can be regarded as the most enduring heritage landscape in Singapore, cast by “the long shadow of 1942”.

Conclusion

The years since 1942 have seen the co-existence of three generations at the time of writing in 2012 - those who experienced the war and occupation, those who were born shortly thereafter with no lived memory of the period, and those for whom 1942 may seem a distant history lesson.

For the generation who lived through the war and occupation, 1942 was a critical year that had in many ways shaped their outlook on life. The effects of war and occupation had a direct or experiential impact on this generation. The memories are deeper, prolonged, and in many cases, traumatic and unhealed. These unhealed memories in their private silence remind us of a harsh legacy of the war and occupation.

While time progresses and commemorative anniversaries come and go, in remembering the past, there is a process of interpretation and re-interpretation in accordance with our present ideas of what is important and what is not4. The door thus remains open for subsequent generations to explore and engage with, and hopefully find relevance in the collective memory of the war and occupation. How the latter will be viewed years from now depends to a large extent on how the distant past can be integrated into the personal memory of maturing or aging individuals who would be experiencing Singapore in its later years of independence. This interaction may well turn out to be a more nuanced and effective way of reclaiming and understanding the past. The narrative role of personal memory becomes important in this sense as a bridge to deal with or cope with the contingent and complex nature of individual experiences whether in war time or in other periods of historical transformations. How the young of 1942 fared individually can hopefully be an empathetic entry point for today’s young generation, given hindsight, to reflect upon, interpret and come to terms with, complementing their personal memory of school lessons on wartime history, learning journeys, and Total Defence Day activities.

In the meantime, the present memorial sites, traces and remains of 1942, together with occasional news reports of war relics still being uncovered, are reminders that the “long shadow of 1942” is far from disappearing completely and that the past while fleeting, still remains with us.

Iskander Mydin is Deputy Director, National Museum of Singapore

Notes

.ashx)