Although museums have become lifestyle destinations, one primary reason people visit them is still education. Whenever they view an exhibition, visitors appreciate the intellectual element of the artefacts and the aesthetics of the display. However, not many are aware that a whole team of professionals work together to create a carefully planned experience that visitors can enjoy.

Besides the curators, exhibition and graphic designers play a large part in creating the right mood and to bring out the beauty in an object. There are lighting professionals and technicians as well as educators who bring the display to life through their publications, programmes and activities. Last and certainly not the least, conservators play a vital role in not only ensuring that theartefacts are in good condition, but also advise the rest of the exhibition team on how best to place and display an artefact. Conservators now also play a crucial role as investigators who help curators go literally deeper into the materials and meanings that make up an artefact. This growing role of the conservator has opened new doors into the existing body of research pursued by curators and academics.

Conservation and preservation

Conservation, in the most general sense, is the long-term endeavour of ensuring that cultural and heritage materials are properly preserved for the benefit of future generations. These materials come in diverse forms, and include paintings, printed or written documents, textiles, garments, ethnographic objects, archaeological artefacts, architectural structures, historic sites and many more.

The preservation of all heritage and cultural artefacts starts with an intimate understanding of the factors that act on and deteriorate all materials. These would include forces such as light, moisture, pollution, pests and physical handling, which can all contribute to hastening the breakdown of materials. In a museum, such parameters are properly controlled and regulated for artefacts in display as well as in storage. This is an important aspect of preservation that is usually not immediately visible or obvious to visitors.

Another key 'invisible' task that goes on behind the scenes is the treatment done to conserve or restore damaged artefacts.

A third facet of conservation work that is gaining slow but steady recognition is the effort to raise a broader awareness of preservation principles and conservation work. This is becoming an important function for a conservator as it is increasingly recognised that the cultural legacy and heritage of a people do not reside solely within the walls of a few museums. More and more people and organisations are contributing to the overall effort ofpreserving and presenting aspects of our culture and heritage. As they seek to maintain the integrity of historical artefacts in private as well as corporate collections, a thorough understanding of sound conservation principles can only be a good development for the long-term preservation of cultural and heritage materials.

Shining (infra-red) light on heritage items

Before the actual act of preservation, it is vital that conservators and curators understand the nature and history of the materials targeted for long-term storage and display. This requires sensitivity by museum workers as they exchange information, discuss, debate and ultimately decide on the most appropriate course of action.

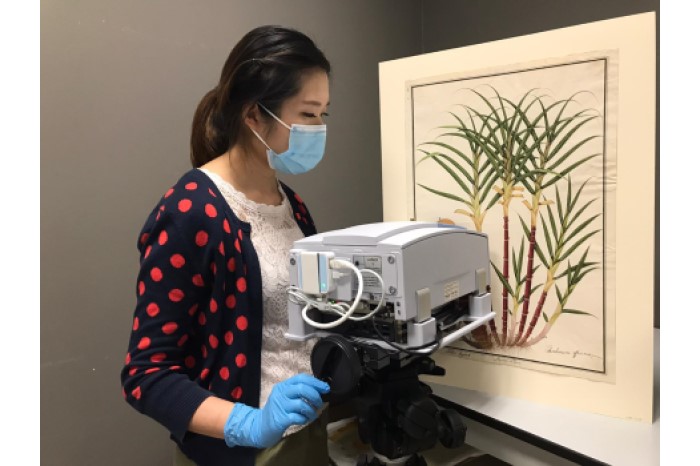

One direct way of extracting information about cultural and heritage artefacts is a detailed technical analysis and examination of the materials themselves. This provides data about the material composition as well as the actual physical condition of these artefacts. Various analysis methods developed and used outside of the field of conservation have been successfully adapted by conservators and scientists to study and understand museum collections.

Some of the non-destructive techniques used to examine and analyse artefacts include Stereo-Microscopy, Ultra-Violet Radiation Fluorescence, X-Radiography and in-situ Fourier-Transform Infra-Red Spectrometry and X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry. On a microscopic scale, which would involve taking a very small sample from the materials, a Paint Cross-Section Analysis, Pigment Particle Analysis and Fibre Analysis could also be carried out. And going even further in terms of magnification, we can also look at surfaces on a nano-scale using a Scanning Electron Microscope and doing elemental analysis using Energy Dispersive Spectrometry. Chemical analyses that have been used successfully in identifying heritage and cultural materials include Gas Chromatography, High-Performance Liquid Chromatography, Mass-Spectrometry and Secondary Ion Mass-Spectrometry.

Of particular utility to art curators and historians is a special sensor sensitive to the infra-red region of the electro-magnetic spectrum, which penetrates paint layers more deeply than visible light. As different materials absorb, reflect and transmit infra-red radiation to varying degrees, the sensor captures an image invisible to the naked eye that reveals various alterations and modifications that an artist had made to the composition of the painting.

Such information can offer new insights to how a work of art evolved as well provide a glimpse into the artist's thought process. We can also gain data about the paints, pigments and techniques used by the artist.

Portrait of an artist: a case study in technical art history:

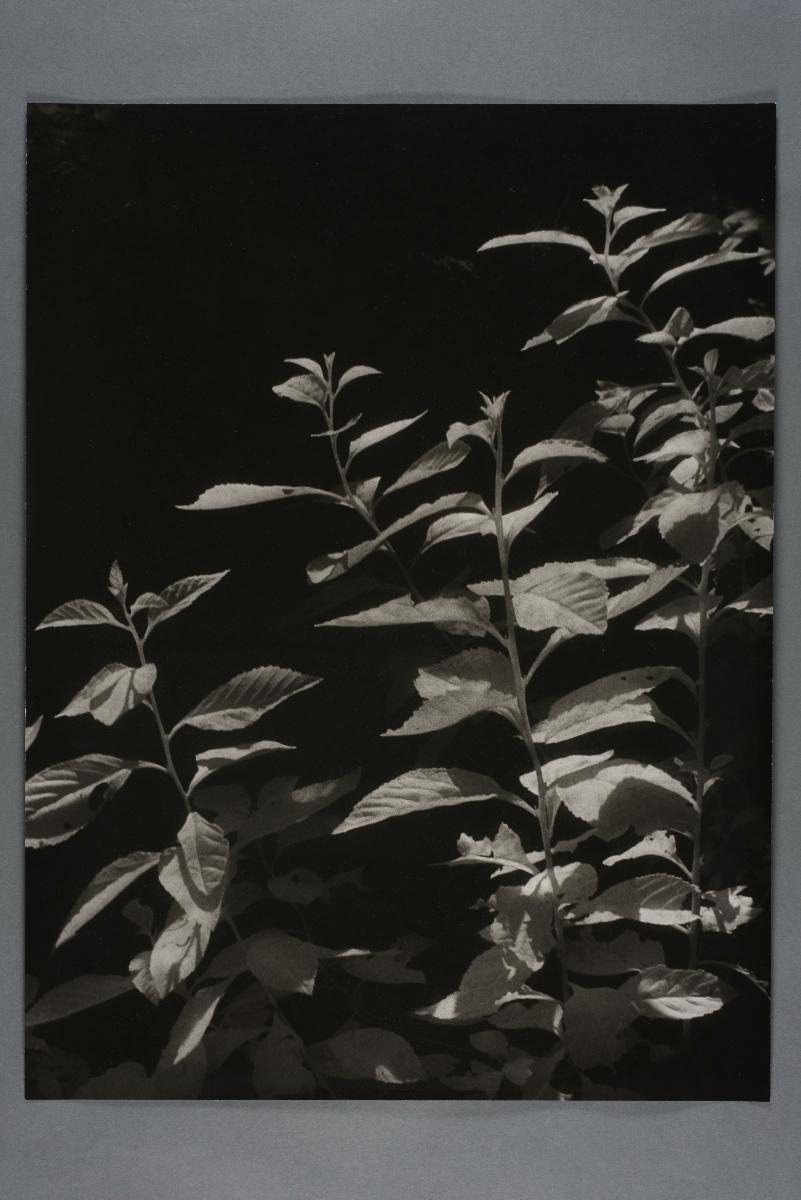

In 2006, the Heritage Conservation Centre made an infra-red imaging study on a series of paintings by Singapore artist Wong Shih Yaw1 as part of a conservation research project2. Infra-red imaging was deemed to be the most appropriate technique as this method does not require any samples to be taken from the paintings and is therefore non-destructive. This is an important consideration in the work of conservation to ensure that no harm is done to the artefacts that we examine or treat.

From studying Wong's paintings in infra-red, we could conclude that the artist is extremely meticulous in ensuring that his draft composition is accurately depicted on the canvas or board before he finishes with paints. This is evident in Wong's use of grid lines in describing circular objects, such as plates and bowls, in his exquisite and intimate Still Life Series. In his larger work, 'Resurrection of Christ', we could discern two distinct changes made to the overall composition. It was also possible to determine areas of the painting that the artist had worked on to a greater degree when we positioned the infra-red light source behind the canvas to obtain a transmitted infra-red image4.

The infra-red images of the composition and alterations made by Wong helped to forge a larger understanding of his working and thought processes. An informal interview with the artist earlier this year confirmed and further discussed the findings. This exchange also opened up new grounds for study, particularly in how the artist decided on the use of his sketches and assembled the images for the final painting.

Such information about a painting's materials and construction can play a crucial role in the on-going quest for meaning and interpretation of an artist's oeuvre. Similar technical examinations and analyses also serve to reveal valuable information about most, if not all other, artefacts held in museum collections. A combination of various technical examination and analytical methods can offer a unique perspective that greatly enhances existing knowledge from historical records and facilitates a richer interpretation of cultural and heritage artefacts.

Principles of conservation

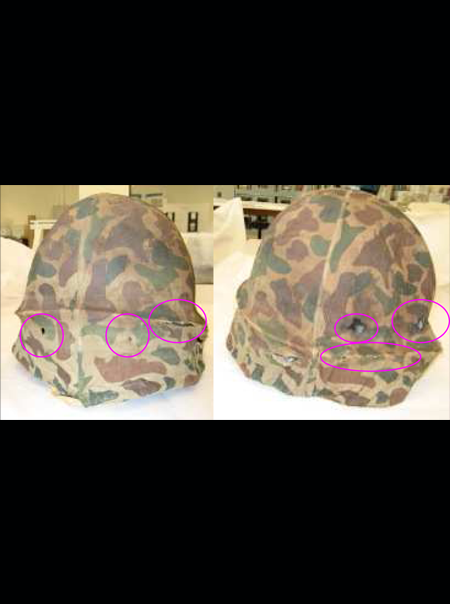

Only upon the completion of a detailed technical examination would conservation treatment be undertaken. Conservators hope to understand as much as possible about the artefact so that decisions on treatment methods and materials can be made with full knowledge of their long term implications.

|

|

|

Conservators adhere to three guiding principles in order to minimise and reduce the impact of any negative long-term effects of our actions. These broad principles are:

(i) Minimal intervention;

(ii) Stability; and

(iii) Reversibility.

The principle of minimal intervention arises from the recognition that conservation and restoration work can significantly alter the look and feel of an artefact. Hence, in order to retain as much of the original material and appearance of an artefact, conservation treatments must target only the damaged area, not more and not less. This calls for very accurate judgment in the use of the most appropriate materials and techniques in the right measure to address the problem at hand.

All conservation treatments and efforts seek to achieve the long-term preservation of artefacts. Hence, any new materials added to repair or support these artefacts must be physically and chemically stable in the long-term as well. There should be no risk of detrimental side effects that could arise from the use of unsuitable or inferior materials.

The final principle of reversibility is a tricky one, as it is more of an ideal than a practical feasibility. This is because conservators hope that whatever additional materials are used to repair an artefact will be removable, so that a better technique or material can be applied in the future. However, this is not always the case due to existing technological limitations, and so it is necessary to strike a balance at times between using materials that are inherently stable but not easily removed and the need to ensure that present-day work would not impede future conservation efforts on the same artefact.

The role of a conservator in a museum is both challenging and increasingly varied. We are experiencing a significant shift from those days when restorers toiled in anonymity and unremarked in a 'backroom' to turn out beautifully repaired artefacts. Today, a conservator is expected to be not only technically skilful, but also scientifically inclined and unabashedly articulate. Casting an eye at the concerns of other stakeholders and lay workers in the field, the conservator must now be an advocate for the long-term preservation needs of our culture and heritage. As such, the conservator's pursuit of posterity is now increasingly a visible manifestation of our growing national interest in the past, and for all the better too.

By Lawrence Chin

Lawrence Chin is formerly Senior Conservator (Paintings), Heritage Conservation Centre. This article was first published in beMUSE, Vol.01 Issue.02, Jan-Mar 2008, National Heritage Board, pp.52-55.

References:

[1] See article 'From Rawness to Restraint' by Low Sze Wee.

2 Ms. Sylvia Haliman, who worked as a conservation intern at the Heritage Conservation Centre, was instrumental in the capture and assembly of the infra-red digital images for this series of technical examination of Wong Shih Yaw's paintings.

3 See artist's own account of his creative process on his blog at - http://sealedman.blogspot.com/search?q=The+Resurrection+of+Christ

4 See accompanying article 'What Lies Beneath' by Lawrence Chin.