Wayang Peranakan

Wayang peranakan is a theatre form that was derived from bangsawan, a type of Malay theatre, in the early 20th century. It is performed by the Chinese Peranakan in the Baba Malay language.

Wayang peranakan was originally staged to raise funds for charitable causes. World War II halted performances. The art form experienced a revival in the 1950s before disappearing altogether till the 1980s. It made a comeback in 1984 with a staging by the Gunong Sayang Association (GSA), a cultural organisation established in 1910 to promote social interaction among the Peranakan community. GSA has been staging wayang peranakan almost every year since then.

Geographic Location

Wayang peranakan performances are staged in Singapore and attended by Chinese Peranakan from Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and Australia.

Communities Involved

In the early 20th century, bangsawan shows included Malay, Eurasian, and Chinese performers. It was not until the 1920s that wayang peranakan was performed by an all-Peranakan cast. Today, the Peranakan Cina, or the Chinese Peranakan, in Singapore are typically the only people staging it.

Peranakan communities are those that settled in this region generations ago, intermarried with local Malays and acquired many of their traditions. Besides the Chinese Peranakan, there are Jawi Peranakan, Indian Peranakan, and even Portuguese Peranakan and Yahudi (Jewish).

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

The scripts for today’s wayang peranakan shows are written by members of the GSA. According to Mr Frederick Soh (Vice-President of GSA at the time of writing), there were no scripts in the past, only a summary of the storyline. Thus, actors spoke ad lib, resulting in impromptu dialogue and performances lasting three to four hours. There would thus be different versions of a show on different days, says Mr Soh. Scripts were introduced in 1984 by the GSA to prevent the shows from going beyond the time that the theatre had been booked for.

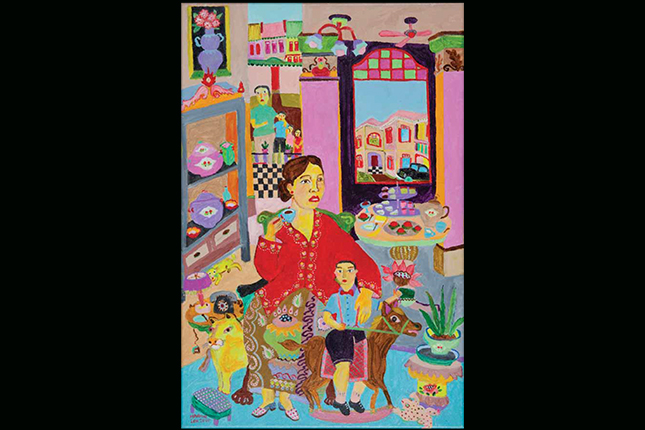

In contrast to wayang peranakan performances of the past, when Chinese legends provided the narratives for plots, today’s shows revolve around the domestic conflicts and difficulties in a Peranakan household. The central figures are the elderly widowed mother, her son, and his wife or wife-to-be. The performances also usually include the family’s non-Peranakan amah (domestic helper) or neighbour to highlight differences between the Peranakan and non-Peranakan world. These characters are also used for comedic purposes.

Another difference between today’s wayang peranakan performances and those of yesteryear is the exclusion of “extra turns”. Mr Soh explains, “Extra turns were when singers came out and sang while the crew frantically changed the props, tables, and chairs, and all that. After the curtains opened, it would be the next scene. When the curtains closed again after the scene, the singers would sing again.” These musical interludes are redundant now since props are on rollers, which makes scene-changing “quite seamless”.

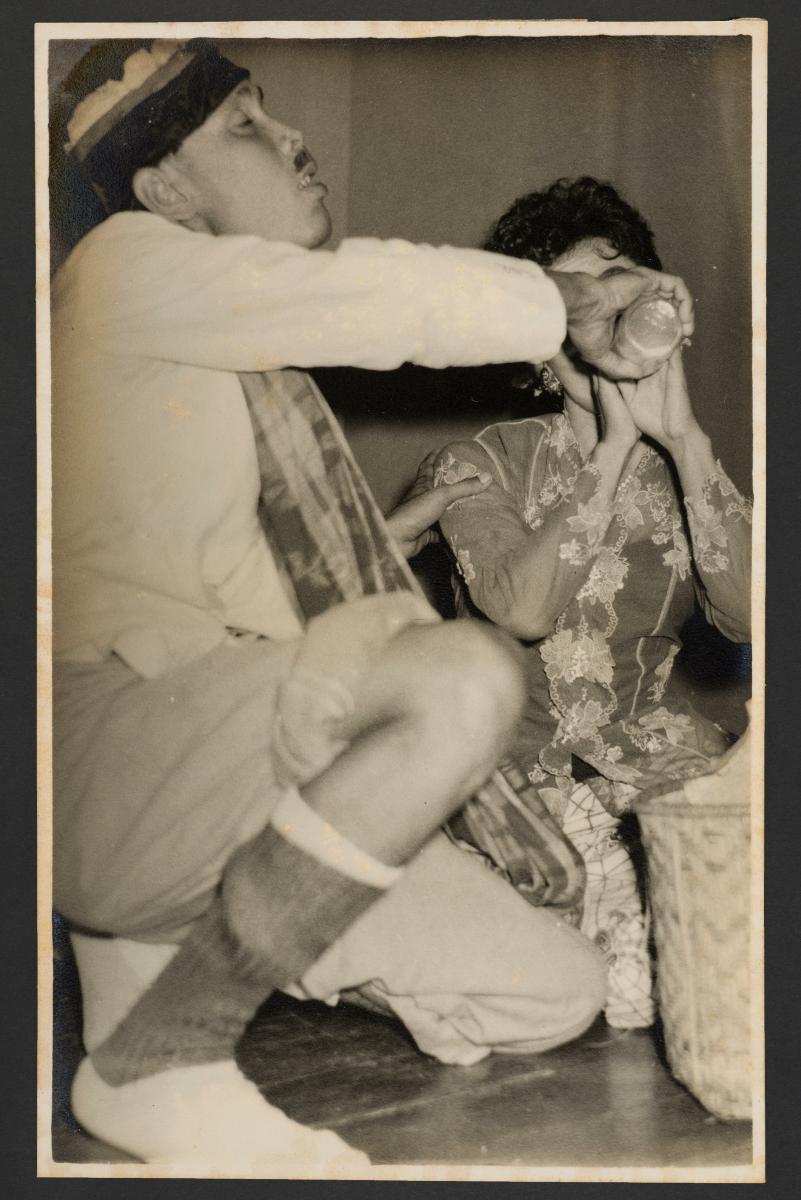

Female impersonation is a distinctive characteristic of wayang peranakan. In the past, the Chinese Peranakan considered it improper for women from their community to be seen on stage. Male actors thus took on the roles of women in the early years of wayang peranakan. It was only in 1980 that the GSA allowed women to join as members and act on stage. However, it has kept its tradition of female impersonation alive by reserving a few roles, such as that of the amah, for these actors.

Experience of a Practitioner

Mr Soh’s love for wayang peranakan began when he went with his mother to one such show when he was a young boy. He was captivated by seeing his spoken language performed on stage. But it was not until he was in his 30s that he got his chance to star in one. When he heard that there was an audition for a wayang peranakan called Janji Perot (Pre-birth Pact), he, together with the president of GSA (at the time of writing), Mr Alvin Teo, jumped at the opportunity. “After reading the script, we were so happy to be selected to be part of the show. It was later that I found out that only two of us auditioned!”, Mr Soh recalls with a laugh.

Mr Soh says that the GSA’s goal is to perpetuate the Peranakan culture for posterity, and he sees wayang peranakanå as one way to do it. All actors, according to him, are paid only an honorarium – an ang bao (red packet) – for their months of hard work, which often comes with “a commitment of their own personal time”.

Present Status

Mr Soh sees some challenges in safeguarding the art of wayang peranakan. The GSA relies on grants, private donors, and fund-raising bazaars on top of ticket sales for money. With funds being tight, it is now considering putting up shows every two years because of the resources required to stage one.

It is also increasingly difficult to find people who can speak Baba Malay. To address this, the GSA organises classes called Mari Kita Chakap Baba (Let’s speak Baba) to help people learn the language.

Mr Soh feels that many young people view wayang peranakan as “old fashioned” and think that “there are so many activities that are more interesting than it”. He acknowledges that he himself started in wayang peranakan when he was in his 30s. He hopes that, like himself, young people will start to look for their roots.

Mr Soh says that the Chinese Peranakan belong to a hybrid culture and are not just Chinese, hence, “it would be a waste if this culture is not preserved”.

References

Reference No.: ICH-051

Date of Inclusion: March 2019

References

Brandon, James R. and Martin Banham. The Cambridge Guide to Asian Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Ching Fatt Yong, Julio Antonio Gonzalo and Manuel Mar¡a Carreira. Tan Kah-kee: The making of an Overseas Chinese legend. Singapore: World Scientific, 2014.

Chong, Alan. Great Peranakans: Fifty remarkable lives. Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, 2015.

Gwee, William Thian Hock. “An expert’s opinion”, The Peranakan Association Newsletter September, 1995.

Lee, Peter. “Role reversals”, The Peranakan July – September 2002.

Lim, Brandon Albert. Staging “Peranakan-ness”: A cultural history of the Gunong Sayang Association’s Wayang Peranakan, 1985-95.

Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts. Singapore: Department of History, National University of Singapore, 2011.

Lim, Brandon and Norman Cho. “Treading the boards of history”, The Peranakan 3, 2011, pp. 3-7.

Meddegoda, Chinthaka Prageeth, and Jähnichen, Gisa. Hindustani Traces in Malay Ghazal: ‘A song, so old and yet still famous’. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016.

Rahmah Bujang and Mohd. Effindi Samsuddin. “Bangsawan: Creative patterns in production”, Asian Theatre Journal 30(1): 122-144, 2013.Wee-Hoefer, Cynthia. “Gwee Peng Kwee: the romantic master of dondang sayang”, The Peranakan. January – March 1999.